What can the Development Corridor mega-project tell us about how Sisi will govern?

In a spate of television interviews during the final stretch of the campaign, presidential hopeful Abdel Fattah al-Sisi spoke of the entrenched structural problems facing the nation—an economic rut so deep that Egyptians could not hope to “run” from it, but instead must “jump” out of it. To surmount the prevailing obstacles, Sisi prescribed a set of requisite virtues that Egyptians are all too familiar with—patience, perseverance, sacrifice—but he also proffered his most specific plan yet to boost the economy: a mega-project known as the Development Corridor.

What is the Development Corridor? And what would its (attempted) realization reveal about a Sisi government?

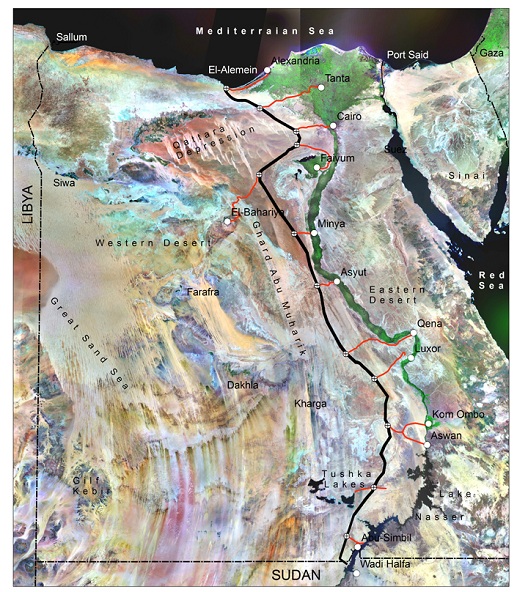

The Development Corridor is a plan to create a completely new urban corridor running the length of Egypt, from the Mediterranean to Sudan, parallel to the Nile Valley, twenty miles into the Western Desert. The backbone of the corridor is a north-south eight-lane super-highway and railway infrastructure with lateral connections to current population centers. This terrestrial transportation, plus an envisioned eight new airports, would ease and accelerate the circulatory system of Egypt’s economy. Along the corridor, forty-eight new cities would be built to eventually house thirty million Egyptians. One of the principal goals of the project is to halt urban encroachment on the precious arable land of the Nile Valley, which has resulted in dwindling agricultural yields and harm to the economy.

The idea was initially conceived in the 1980s by the Egyptian-American scientist Farouk al-Baz, who pitched the plan to successive governments. After decades of advocacy—and even formal rejection by Mubarak’s cabinet in 2005 for its hefty price tag—Baz persuaded the interim SCAF government of the merits of the Development Corridor, an embrace that has carried over into the nascent Sisi administration. Baz, who has been described as “the brain” of Sisi’s inner circle of economic development advisors, told reporters that the Corridor is the “keystone” of Sisi’s development agenda.

We should not disparage the Corridor for being an old idea, or seeming like a pipe dream. The Suez Canal was dreamt decades before Ferdinand de Lesseps connected the Red and Mediterranean Seas with 1.5 million shovels swinging in the desert, and the project was regularly dismissed as folly bordering on insanity before it succeeded and subsequently transformed the global economy.

And while Egyptians might prefer an emphasis on addressing immediate economic concerns rather than turning energies to monumental moonshots, Sisi’s motivating impulse is understandable: mega solutions for mega problems, a massive public works project providing a Keynesian shot in the arm for a moribund employment environment, and a marquee undertaking to inspire national pride.

And let us put aside for now the legitimate concern of whether the Development Corridor is, well, a good idea. (In 2011, a conference of 180 prominent Egyptian scientists unanimously rejected the mega-project; and one wonders how Sisi might power forty-eight new cities when it’s already a struggle to keep the lights on in Cairo.) Instead, let us look at the Development Corridor—much like the energy crisis—as where the rubber hits the road; a case study of practical problem solving, planning, and governance.

Indeed, the mega-project is interesting for what it will show us about how Sisi will rule. Does Sisi possess the governance chops to pull off massive and massively complex initiatives? He has proven himself an adept government insider and a magnetic populist figure, but can he actually steer the gigantic, lumbering Egyptian state? Can he balance the interests of multiple constituencies in a deeply polarized Egypt, where patience and state cash have run thin?

Consider the multiple, disparate resources, agencies, and actors required to successfully complete the Development Corridor. Financing will require a multinational effort melding Gulf state money, international investment and, apparently, a scheme to have Egyptian ex-pats to donate or invest $10 per year—all coordinated by the Ministry of Finance and harmonized with the state budget. Will the processes of planning and financing be open and smart, or opaque like the doomed Toshka mega-nothing mega-project? Construction of highways and railroads will involve cooperation and action from the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Public Works, the Ministry of Labor, the Ministry of Interior, and officials in half a dozen governorates, all in conjunction with private construction companies. The construction of new cities and airports will add to this mix the already taxed Ministry of Electricity and the Ministry of Water. What will the necessary administrative infrastructure look like? A project with so many moving parts and so much money sloshing about will surely put to the test Sisi’s naïve theory of corruption. And, if the construction phase of the project comes to fruition, will Sisi be able to lure 30 million Egyptians to his modernist utopia? Will he be able to overcome the state’s checkered history with population resettlement?

Egyptian rulers have long shown a taste for mega-projects—to transform Egypt and to cement their legacy. Recent experience has shown that these projects exist more reliably as dreams, but in implementation are liable to become famously epic failures. Thus we might be inclined to dismiss the Development Corridor as grandiose campaign talk, especially when we hear that, on top of the Development Corridor (with an optimistic price tag of $140 billion), Sisi has aspirations to collaborate with Gulf countries to also build the Suez Canal Corridor and the Qattara Depression Project.

In one of his pre-election interviews, Sisi was asked about frequent comparisons with Gamal Abdel Nasser, another military president with grand ambitions for mega-projects. “I wish I was like Nasser,” Sisi responded. “Nasser was not just a portrait on walls for Egyptians but a photo and voice carved in their hearts.” That is, not just any portrait, but a beloved portrait. Let us see if Sisi is content with the image of a ruler—and the mere blueprints of a fantastic megaproject—or if he will deign to do the dirty work necessary to jump the country out of its rut.

Matthew Hall is Assistant Director at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East at the Atlantic Council.