A Q&A With Dr. James Noyes, Part II of III

A Q&A With Dr. James Noyes, Part II of III

More than merely a terror group, the Islamic State is a violent state-building project, conquering territory with the intent to rule. In clearing the landscape to impose this political agenda, an essential component of the group’s military advance has been the systematic destruction of holy sites perceived to be at odds with the puritanical vision of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS).

As we explored in Part I of our interview with Dr. James Noyes, ISIS’ program of iconoclastic destruction is at once theological and political. Acts of iconoclasm help to define the politico-religious frontiers of the so-called Caliphate.

In Part II of our interview we explore the contradictions of a group that, on one hand, expends great effort to declaim and destroy graven images, while on the other, is a profligate producer of propagandist imagery.

• Beyond the battlefield, this is a war of imagery and online propaganda. ISIS is renowned for its well-oiled PR machine and savvy social media presence. Do you see a tension between the group’s image-making and image-breaking? For example, a frequently shared image is the celebratory obituary of a fallen fighter, his face photographed in beatific pose, ostensibly smiling because he has entered heaven. The effect is hero worship, almost hagiographic. How does this man-made representation (digitally-graven image) jibe with the concept of shirk?

On the surface, it does seem strange that Sunni militants expounding tawhid would produce graven images of their fallen mujahideen. Images of martyrs and saints are at the heart of the debate over iconoclasm, and are typically associated with the Shia and with Christians in the Orthodox and Catholic traditions—exactly those cultures which are being attacked by ISIS today. On this level, I agree that these images of fallen fighters provide another example of the kind of overlaps and conflations that we have been discussing.

However, this type of “hagiography” is actually less to do with shirk and more with another belief widely held in militant circles: that the bodies of martyrs (shaheed) are incorruptible. On Twitter, many of the photographs you mention are juxtaposed with images of dead government soldiers. They are accompanied by claims that even after several days in the desert, the bodies of the ISIS fighters remain intact while the bodies of their enemies rot.

This is seen as a sign from God, and ISIS’ depiction of intact, “sweet-smelling” bodies of fallen fighters draws on scripture and scholarship which elevates the shaheed. In the Sunnah, it is stated that Allah prohibited the earth from consuming the bodies of prophets. According to some scholars, this applies also to martyrs. It also has a territorial significance—for a long as the body of a shaheed does not rot, the land in which he lies cannot be claimed by someone else. The land of the Islamic State is now full of such bodies, reinforcing their own territorial claims.

Nor is this trend new to the Islamic State. It echoes the claims of other recent conflicts. During the Soviet War in Afghanistan, for example, claims circulated around the mujahideen that the bodies of shaheed were not touched by the same dogs who “devoured the bodies of the Communists,” and that they remained sweet-smelling even after years of burial. During the Bosnian War, these stories became widespread, often promoted by the same mujahideen who had fought in Afghanistan.

On that level, ISIS’ depiction of fallen fighters is part of a wider trend among the mujahideen. In terms of producing images of these fighters on social media, I would argue that this is essentially due to the tools available to ISIS today. In 1980s Afghanistan and 1990s Bosnia, stories of incorruptible bodies depended on oral and written transmission between the mujahideen. Today, ISIS has the internet.

Read Part I of III here: Iconoclasm and the Islamic State: Razing Shrines to Draw New Borders

Forthcoming, Part III of III: Whither the Islamic State? Will ISIS’ imposed iconoclastic agenda alienate local populations?

Matthew Hall is an assistant director with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

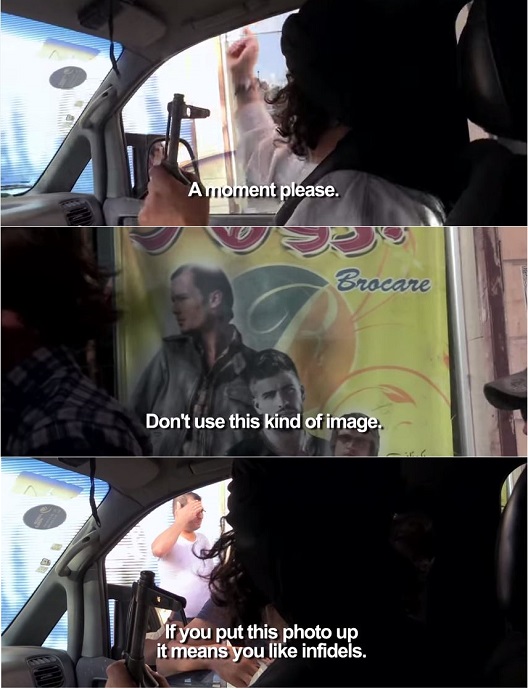

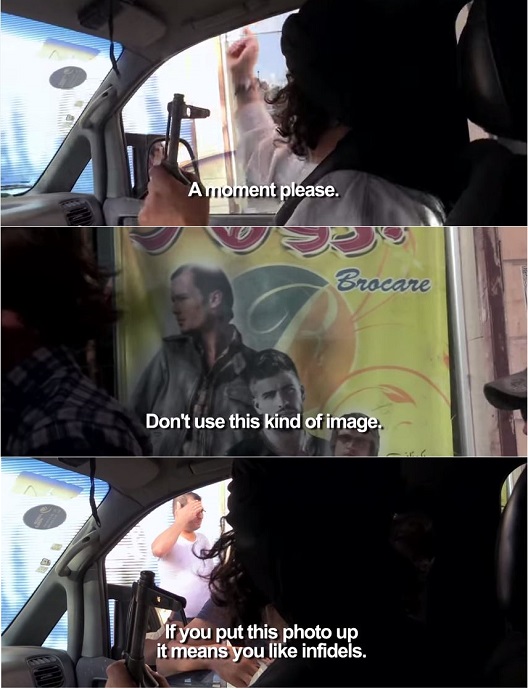

Image: An armed member of the mutawa (morality police) on patrol in ISIS-controlled Raqqa enforces strictures against forbidden images. (Photo: Vice News Screenshot/documentary/"Enforcing Sharia in Raqqa: The Islamic State")