In the midst of a series of court rulings targeting young Egyptian activists on charges related to the controversial protest law, the life sentence handed to Ahmed Douma has been the most shocking. Charged with illegal assembly, assaulting security forces, and vandalism, Douma was also fined 17 million Egyptian Pounds for the alleged damage he inflicted on government properties during the confrontations known as the “Cabinet Clashes.” The sentence, the harshest against activists known for their role in toppling Hosni Mubarak’s regime in 2011, brings to the forefront pressing questions about the politicization of court rulings.

In the midst of a series of court rulings targeting young Egyptian activists on charges related to the controversial protest law, the life sentence handed to Ahmed Douma has been the most shocking. Charged with illegal assembly, assaulting security forces, and vandalism, Douma was also fined 17 million Egyptian Pounds for the alleged damage he inflicted on government properties during the confrontations known as the “Cabinet Clashes.” The sentence, the harshest against activists known for their role in toppling Hosni Mubarak’s regime in 2011, brings to the forefront pressing questions about the politicization of court rulings.

The Cabinet Clashes, which took place in December 2011, proved to be the precursor for four months of violence. Following the appointment of Mubarak-era politician, Kamal al-Ganzoury as Prime Minister, protesters staged a sit-in in front of the Cabinet headquarters in downtown Cairo. Douma, one of the sit-in organizers, said clashes broke out at the sit-in after police kidnapped and beat protester Ibrahim Aboudy. In the violence that followed, seventeen were killed and hundreds injured. Authorities accuses protesters of lobbing stones at the cabinet headquarters, while protesters said security personnel threw rocks and bricks on protesters from the roof of the cabinet and parliamentary buildings. Douma was tried along with 229 other defendants, he was the only one in custody at the time of sentencing. The collective 17 million Egyptian pound find is, theoretically, his to pay.

Douma, who participated in the January 25 revolution, became more prominent following ousted president Mohamed Morsi’s election, becoming one of his most vocal critics. The activist was involved in violent clashes at the Muslim Brotherhood’s Moqattam headquarters in March 2013, and ordered detained as a result. He was also detained on charges of insulting Morsi, and was given a six month suspended sentence. In December 2013, under interim President Adly Mansour, he was detained, and later sentenced to three years in prison on charges of violating the protest law. While in prison, he was referred to trial over charges relating to the Cabinet Clashes.

The judge presiding over the trial, Nagy Shehata, has become an internationally known figure in Egypt’s judiciary. He sentenced the Al Jazeera journalists to seven to ten years in prison, as well as sentencing 188 to death on charges related to the killing of eleven police officers in Kerdasa. Douma’s lawyers, supported by the Lawyer’s Syndicate, had decided to boycott the Cabinet Clashes trial and will be appealing the verdict. The decision to boycott came as a result of Shehata’s political views, because he spoke to the media while the trial was ongoing, and because he had impeded the defense team, refusing their witnesses and depriving them of access to case files.

Amr Imam, a member of Douma’s defense team and a lawyer at the Hisham Mubarak Law Center, said that Shehata, known as “the judge of executions,” is also known for his anti-revolutionary views. “Nagy Shehata is famous for his rivalry to the revolution, which he constantly declares,” Imam said, adding that the defense team requested the referral of the case to another court for this reason but were rejected. Shehata also referred human rights lawyer Khaled Ali to prosecution after the latter accused him of bias. According to Imam, Shehata’s actions are indicative of the politicization of the judiciary. “These declarations indicate that the judiciary is now manipulated by the state. Shehata is issuing verdicts for the sake of stability not justice,” Imam explained. Prior to issuing the final verdict, Shehata sentenced Douma to another three years in prison for contempt of court.

Activist and filmmaker Khaled Youssef described the verdict as unfair, juxtaposing it with the acquittal of former President Hosni Mubarak and his aides on various charges. “So the authorities failed to prove the 30-year long corruption of Mubarak and his men, yet managed to prove the crimes of Douma? How is this possible?” he asked. Youssef, a supporter of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi during his presidential campaign, described Douma as “an honorable freedom fighter.”

In a joint statement issued immediately after the verdict, seventeen Egyptian rights organizations condemned what they saw as a serious collapse in the justice system in Egypt. “While such harsh verdicts are issued against protestors in the cabinet clashes, none of the police and army personnel were held accountable for the violations they committed during those clashes including killing protestors and stripping women of their clothes,” the statement said. It called on the Supreme Council of the Judiciary to intervene in order to put an end to court rulings becoming personal vendettas.

Activist and member of the National Council for human rights Hafez Abu Saeda also objected to the verdict, arguing that the punishment did not fit the crime. Abu Saeda added that he was hopeful that a presidential pardon will result in Douma’s release. Ahmed Ragheb, director National Community for Human Rights, however, noted that presidential pardons are not the solution. “Besides undermining the independence of the judiciary, presidential pardons only focus on famous activists while many unknown ones are also in jail,” he said, adding that Sisi has admitted to the incarceration of many innocent Egyptians. “This means he is aware that there is a serious problem with justice in Egypt.”

Douma was among the activists named by Senator John McCain, when he urged Sisi to release those wrongfully imprisoned in Egypt. The US State Department and European Union similarly expressed concern over the verdict. When asked about Douma, among others, weeks earlier, Sisi, however, deflected the question: “Our protest law is derived from the French, German, and Swiss laws that organize protests. Everyone has a right to protest through notifying the authorities to obtain permission. For the activists, this was about demonstratively violating this law. Ninety-million Egyptians want food and water. Would your country invest in us if the protests continued day and night?”

Upon hearing his sentence, Douma reportedly clapped, saying, “I am happy with the verdict!” And the judge responded, “Do you think you are in Tahrir or what? I will give you another three years.” The judge’s response is, unfortunately, typical of a sizable portion of the Egyptian population. The recent resentment of any opposition to the popularly supported regime has extended to revolutionary youth and even to the very symbol of protest—Tahrir Square. Other activists behind bars including April 6 co-founder Ahmed Maher, Alaa Abdel Fattah, Yara Sallam, and Sanaa Seif, were among the first to face this kind of resentment.

Immediately after Douma’s verdict was announced, a character-assassination campaign supporting his incarceration started in media outlets and on social networks. A video of a TV interview Douma gave to an Egyptian private channel was cited as proof of his crime. In it, he admits he and his fellow revolutionaries used Molotov cocktails to defend themselves against attacks by security forces, stressing that they never targeted the National Archives building, which he is accused of burning down. “I have never targeted the National Archives building or any other buildings,” said Douma in the interview. “I was using Molotov cocktails in response to gunshots. It is absurd to assume that I will allow them to kill me because they are staying in a ‘sacred’ building. I would have done same thing had they been shooting from a mosque because they already desecrated the place.’” The only part of the video that made the rounds following the verdict, however, was where Douma says, “I, Ahmed Douma, confess that I used Molotov cocktails.”

The verdict was also followed by claims that Douma is a member of Hamas—the Palestinian movement linked to the Muslim Brotherhood. Dalia Ziada, executive director of the pro-regime Egyptian Center for Free Democracy Studies. Ziada posted documents reportedly issued by the Interior Minister in Gaza, which ordered “facilitating Douma’s stay in the [Gaza] Strip and providing him with the necessary weapons, clothes, and money.” The documents, which cannot be independently verified, also went viral and were widely shared by supporters of the verdict as proof of Douma’s crimes.

Even though Douma’s plight is always perceived as part of a bigger dilemma facing activists who played an active role in the January 25 Revolution, the remarkable harshness of the sentence against him has garnered global attention. While other activists are facing anywhere from three to five years in prison, Douma’s life sentence stems from charges of burning down the National Archives, a charge he has denied since 2012. “I did not burn it,” he said in his first testimony in the case. “I was actually trying with others to save it.” He repeated the same statement in the last session in February 2015. “There are videos that show who burnt the building but the judge paid no attention to them,” he said. “The defense team also submitted several complaints against the armed men in police uniform who attacked protestors from roof tops but that was totally ignored.” The hefty fine, mainly for the damages sustained in the National Archives building, is also unprecedented.

It remains to be seen whether such harsh verdicts herald a new era of a crippling clampdown on revolutionary figures, the type of which is apparently met with a great deal of popular support, or if it is the work of an errant judge exacting revenge on the January 25 revolution.

Sonia Farid, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of English Literature at Cairo University. She is a translator, editor, and political activist. Her social work focuses on political awareness and women’s rights and her writing interests include society, politics, and security in Egypt. She took part in a number of local and international conferences and published several academic papers. She can be reached at soniafarid@gmail.com

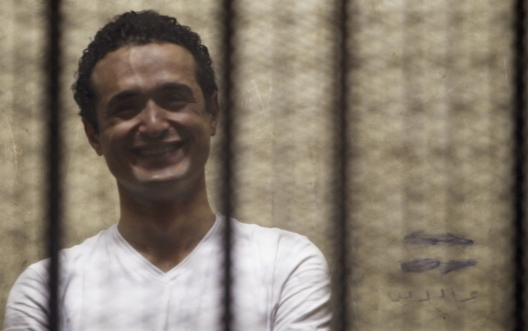

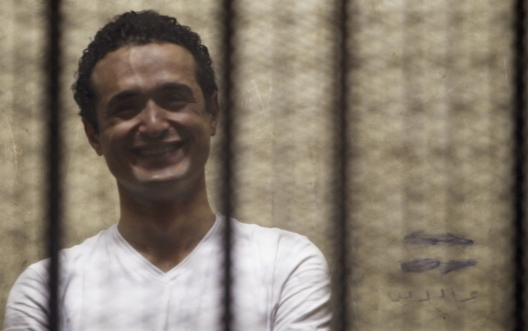

Image: Photo: Egyptian activist Ahmed Douma smiles from behind bars during his trial at the New Cairo court, on the outskirts of Cairo June 3, 2013. (Reuters)