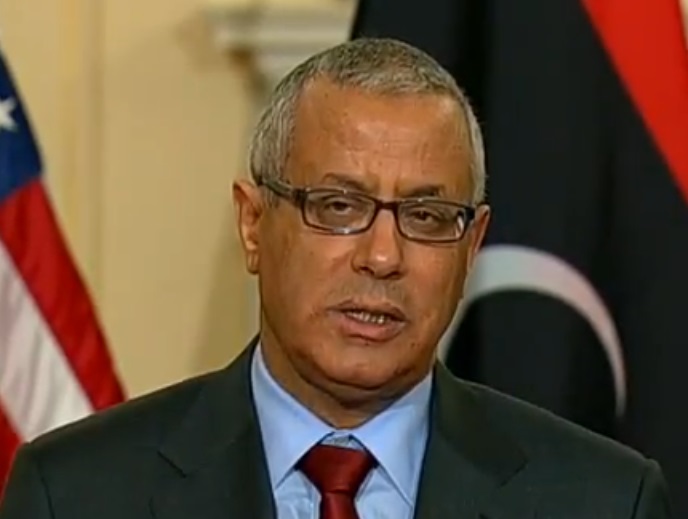

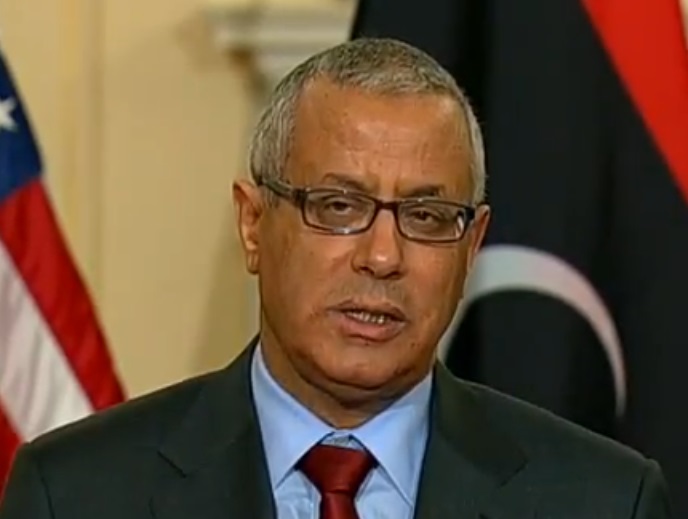

Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zidan has a full plate as he tries to steer the country towards empowering state institutions and building a nation. The recent resignation of his deputy prime minister, Awadh al-Barassi, followed by the shocking resignation of Interior Minister Mohammed Khalifa al-Sheikh after his appointment less than four months ago, point to the level of dysfunction and crisis gripping the cabinet. Both members of government launched sharp criticism at the prime minister’s management of the cabinet and his lack of leadership. Rumors of corrupt officials within Zidan’s inner circle are percolating throughout society. Finding himself increasingly on the defense at every public appearance, Zidan is stuck between a rock and a hard place these days.

Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zidan has a full plate as he tries to steer the country towards empowering state institutions and building a nation. The recent resignation of his deputy prime minister, Awadh al-Barassi, followed by the shocking resignation of Interior Minister Mohammed Khalifa al-Sheikh after his appointment less than four months ago, point to the level of dysfunction and crisis gripping the cabinet. Both members of government launched sharp criticism at the prime minister’s management of the cabinet and his lack of leadership. Rumors of corrupt officials within Zidan’s inner circle are percolating throughout society. Finding himself increasingly on the defense at every public appearance, Zidan is stuck between a rock and a hard place these days.

From the security point of view, very little progress can be cited. Clashes between militias continue unabated. The control of the state in the eastern region is minimal, while in the south, it is practically non-existent. There is continuous news about the increasing presence of jihadist groups in Libyan territory infiltrated by elements from other parts of the Arab world. Increasing criminality empowers gangs active in human and drug trafficking. Targeted assassinations and random kidnappings of government officials, businessmen, and bank managers continue without recourse. Corruption is perceived, rightly or wrongly, as being rampant and widespread in every sector of society.

The political situation is no better. Political parties are driven less by leadership than by the personal motivations of its members. Recently, the two main blocs—the National Forces Alliance and the Muslim Brotherhood—have de facto dissolved themselves by giving their members total freedom to decide whether to actively participate in the General National Congress (GNC). Moreover, within the GNC, there is tension regarding the implementation of the electoral law that would guide the election of a committee to draft the constitution. A lack of a capacity to act or bureaucratic and financial hurdles paralyze most ministry officials. Another oft-cited problem is the absence of a clear legal framework that defines the distribution of power and duties between the government ministries and the GNC. From the economic point of view, infrastructure projects remain stalled, and the government has gained no ground in the creation of jobs or provision of services. Exacerbating these challenges, labor strikes in the oil fields taking place at most sites severely disrupt oil exports with evident repercussions on the country’s revenues.

What is causing this demoralizing scene, and what is hampering progress in each of these areas? While the downward spiral of Libya’s abysmal situation over the past two years may be attributed, in part, to an ongoing power struggle between two increasingly polarized groups. On one side, the interests of militias from Misrata, parts of Tripoli, some cities of Jebel Nafusa, and other smaller towns are coalescing and acquiring political cover from certain blocs within the GNC loosely associated with Islamist movements. On the other side are the militia from Zintan and the powerful militia of Qaqa, also comprising Zintani citizens officially aligned with the more secular coalition known as the National Forces Alliances led by Mahmoud Jibril. The deterioration of security in the country has further entrenched the opposing sides.

This disheartening picture leaves the everyday observer with the impression that the Libyan state is on the verge of anarchy with no real functioning state institutions. Does this mean that the situation will inevitably lead to an armed confrontation of sorts that will stop the democratic transition and revert the Libyan state back to authoritarianism, much like what is going on in Egypt? This may well seem like the likely consequence, but it is by no means the only possible outcome of the Libyan struggle for democracy.

Civil society organizations and individuals from across Libyan society strive for a plan that represents the only hope for a substantive solution to overcome the current crisis and drives progress toward a successful transition. That solution—the only viable solution at present—is to convene a national dialogue conference. Most observers and political activists in Libya agree that without this step of national reconciliation, no progress can be made in state-building. Many figures, from Zidan to the head of the UN Support Mission in Libya, Tarek Mitri, have identified national dialogue as the only route out of the current crisis. By inviting a cross-section of Libyan society to the table, including Islamists and militias, the national dialogue conference would obligate all participants to state their full commitment to a peaceful transition to a democratic system of government. Extremists or others who are unwilling to make that public commitment will marginalize themselves and lose public standing.

In order to move forward with the national dialogue idea, two outstanding questions must be considered carefully: first, who will lead such an initiative to convene all Libyan groups and forces; and second, once the initiative is taken, how does one proceed in a country where the rule of law is practically absent? The past two years have proven that Libya’s high level of fragmentation and lack of technical capacity requires robust international support. Regarding the organization of a national dialogue, the United Nations has the capacity, experience, and authority to play this role and support the Libyan government and the GNC in their call for a national dialogue conference. The United Nations would assume responsibility for organizing the dialogue and would provide the technical competence and organizational procedures. Given security concerns, the United Nations might consider providing a small police support force to ensure the safety of the conference participants and to patrol the grounds. NATO countries that assisted Libyans in their revolution would be instrumental by leveraging their diplomatic heft to support the national dialogue process, thereby strengthening the legitimacy of the Libyan institutions that called for such an endeavor.

There may be many objections to such a plan, including those who think that the GNC, because of its divisiveness and competing interests, may not support such an initiative. Nevertheless, there is no alternative to giving the national dialogue a chance. There is no way for Libya to save its nascent democracy other than to coalesce the centrifugal forces around a common project. The events in Egypt, increasing disorder in Tunisia, and the mounting threat of criminal activities and jihadi terrorism within Libya mean that the country can no longer afford to delay constructing a unifying, national vision.