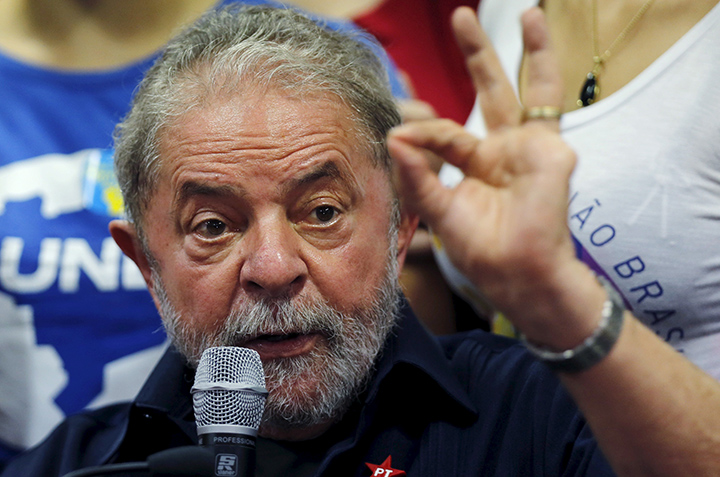

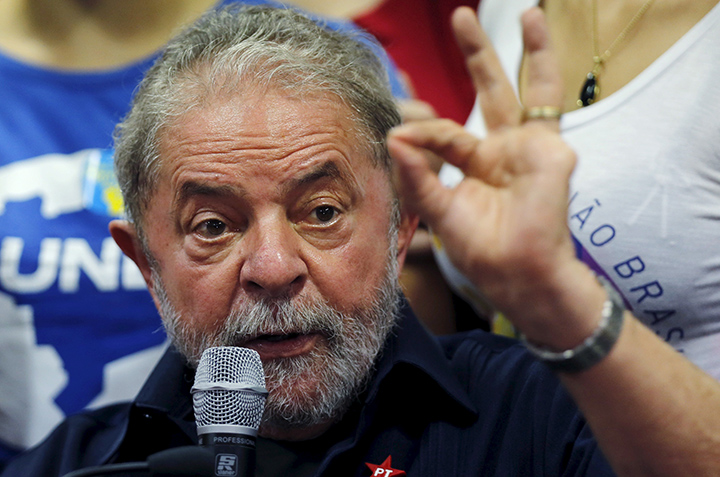

Already under impeachment pressure, Rousseff feels heat from former President Lula’s detention

The brief detention of former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in connection with a federal investigation of a bribery and money laundering scheme turns up the heat on his successor, but it is unlikely that Dilma Rousseff will be impeached in the short term for one simple reason: Brazil has no Plan B.

“Who wants the hot potato of the Brazilian government is the key question to understanding what Brazil is all about, and the answer is: almost nobody,” said Peter Schechter, Director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. “Dilma has got the hot potato and a lot of people in the end will conclude: let her keep it.”

Da Silva’s detention brings the corruption and kickback scandal involving the state oil firm Petrobras one step closer to his protégé, Rousseff, who is already facing impeachment proceedings. Police say a bribery and money laundering scheme financed the ruling Workers’ Party’s campaigns as well as those of other large Brazilian parties. Rousseff has denied knowledge of the bribes and kickbacks at Petrobras, or that she interfered in the investigation.

The President is also under pressure from Brazilians angry over an economic slowdown. In addition, her government has struggled to contain an epidemic of the mosquito-borne Zika virus.

Any benefits of impeaching Rousseff would only be short-lived and would certainly not address the root causes of the crises facing Brazil, said Andrea Murta, an Associate Director in the Latin America Center.

Peter Schechter and Andrea Murta spoke in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts from our interview.

Q: Brazil’s real led global gains and stocks rallied as traders bet that President Rousseff’s impeachment is imminent. Lula’s detention has brought the Petrobras scandal one step closer to his protégé. How will this affect Rousseff’s political fortunes?

Schechter: It is extraordinary that Brazil leapt to celebrations today. We saw people going out into the streets, to stocks rising, and Brazilians feeling a sense of greater confidence that the moment is arriving when the regime will be overturned. The great problem is that no one is very clear on what comes next.

I certainly believe that Lula’s detention, albeit momentary, will make President Rousseff’s fortunes even more precarious, but I also feel that when the storm clouds really come together people will ask: what exactly will come next and who is going to take over this country? Taking over Brazil means taking over a severely recessionary economy, and resentful Brazilians who believe that the blame for much of the country’s ills lies in Brasilia. It is hard for me to imagine which politician is going to volunteer for duty.

Murta: Brazilians are looking for a silver bullet. They think that getting rid of the current government will solve the crisis and turns things around. I don’t think that is going to happen. Even though Dilma’s situation is more precarious and her continuance in power less likely today than it was yesterday, it is not 100 percent clear that she is going to lose her mandate anytime soon, not least because there is no viable alternative to her or her policies. We Brazilians need to stop and think about how to get themselves out of the crisis in the long term.

Q: Is it in Brazil’s best interests for President Rousseff to step down?

Schechter: There is no clear Plan B, therefore, the next step is up to Brazil’s administration of justice, which has to date proven itself to be very efficient and to a large extent the envy of many in Latin America. Impeachment is a political act that requires a majority of Congress and politicians to make decisions that will result in very clear consequences. I am not convinced that these politicians want to be responsible for the consequences that Dilma’s resignation will have.

Murta: Whether or not she continues to be in power is not the biggest concern here. I don’t think Brazil is ready for impeachment. In the economic arena, any immediate benefit of impeachment would be temporary. Indeed, there is a crisis of confidence in place, so there would be a short-term effect of giving Brazilians hope for change. But the roots of the problems would not be touched by simply replacing the government. In the long term, the consequence of such a drastic disruption of the democratic process is unclear.

Q: What have the political problems facing the President meant for Brazil?

Schechter: Brazil is going through a profound midlife crisis. The crisis is financial, economic, political, psychological, medical. It is the perfect storm of problems and Brazil doesn’t seem to be able to catch a break. It was recently announced that ticket sales for the Olympics are going very poorly. There isn’t anything that seems to be going right for the country. For Brazil’s citizens, whom to a large extent are hardworking and innovative, all of this certainly creates a sense of malaise which is very difficult to get out of.

Q: Why is there no unified opposition or an alternative to President Rousseff?

Murta: The opposition hasn’t been able to create a plan for growth or for a different political reality that gathers enough support either from the population or the political elites. The party system in Brazil is weak. Parties hardly ever represent a united front on any concrete platform. This fragmentation has grown over the past decade and, as a result, we have different forces fighting for power, with no one agreeing on which direction the country should go.

A lot of the opposition is also implicated in the same scandals that are bringing the government down. Parts of the opposition and of the government coalition are all implicated in the Petrobras corruption investigation. There has to be someone who is clean or that people trust will not be implicated in the future to represent the new leadership that the country needs.

Schechter: It is not quite clear who the opposition is. The largest party in Brazil is the PMDB (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party). The PMDB is deeply divided about whether to continue an alliance with the government. The second-largest party is the PSDB (Brazilian Social Democracy Party). They are the historic opposition. They have no plans, no proposals, no concrete steps of action. They are a little bit today under the same accusation that the Republicans are here in the United States: all they do is say no.

Then there are the new civil society groups that are seen as interesting because they are clean and they come from the grassroots and not from politics. Right now anything that comes from politics has a whiff of corruption to it that may be unsurmountable. That’s why it is difficult to imagine what Plan B is because Plan B depends on politicians. Brazil right now doesn’t want more politicians.

Murta: The opposition is not united in the call for impeachment. A large portion of the opposition would rather wait for the elections in 2018 without being tainted by the severity of the current crisis.

Schechter: Who wants the hot potato of the Brazilian government is the key question to understanding what Brazil is all about, and the answer is: almost nobody. Dilma has got the hot potato and a lot of people in the end will conclude: let her keep it.

Q: What is the likely fallout of Lula’s arrest on his left-leaning Workers’ Party and the former President’s plans to run again for the top office in 2018?

Schechter: Not good! I would be very surprised if we had another PT (ruling Workers’ Party) President in 2018.

Murta: There are two main consequences. One, I would bet that Lula is not going to get enough support to run anymore. And two, I think this will lead to more polarization, not in support of Lula, but in support of the left in Brazil. There are still some links that the labor party historically had with social movements in Brazil—with worker movements, unions, land reformers—that will react and may even come to the streets in support of the current President, not because they like her but because they don’t want to see a disruption of the results of the election in 2014. The immediate consequence will be higher polarization in the streets of Brazil.

Ashish Kumar Sen is a staff writer at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Brazil’s former President, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, delivers a statement to the media after he was detained for questioning in a federal investigation of a bribery and money laundering scheme in São Paulo, Brazil, on March 4. (Reuters/Paulo Whitaker)