Do all sane people agree that a nuclear weapons-free world would be best? Are nuclear weapons militarily obsolete, desirable only for political posturing? That seems to be the consensus of an influential group of European leaders making the rounds in Washington this week.

Earlier this week, the Atlantic Council hosted a delegation from the Pugwash Conferences and the Top Level Group for a working lunch on the future of the U.S. nuclear posture in Europe. It was a lively and frank exchange of men and women who hold or have held very senior defense and foreign policy-making positions on both sides of the Atlantic and are therefore very steeped in the issues at hand. The discussion was not-for-attribution but the major takeaways are fair game.

Nuclear Weapons Obsolete?

There appears to be a growing sentiment in Europe that nuclear weapons are obsolete, kept around only for symbolic value. Their use is considered so morally reprehensible, the argument goes, that no political leader would dare authorize their use and be forever a pariah. And, if there are no circumstances under which they might be used by Western leaders, then the deterrence argument goes out the window.

The problem with that theory is that desperation changes the utility equation. No sane Japanese government would have provoked war with the United States in 1941. But, facing even worse alternatives, they threw a Hail Mary with the Pearl Harbor bombing and hoped for the best.

Could China or Russia be backed into a corner and become so desperate that they’d launch a nuclear first strike? It’s pretty hard to imagine. Then again, the mere fact that they have that theoretical option makes it less likely that they’ll be backed into a corner.

It’s a little easier to come up with a scenario under which North Korea’s Kim Jong Il or a nuclear-empowered Iranian ayatollah might see nuclear weapons as a plausible option. Or, goodness knows, India and Pakistan. More likely, though, the sense of security that comes with being a nuclear possessor will prevent conflicts that might otherwise have been tenable.

Clausewitz taught us that war and politics are inextricably linked. So, the distinction between the "political" and "military" viability of nuclear weapons is one without meaning. The bottom line is that deterrence theory still works, at least amongst state actors. After all, no nuclear power has ever been attacked by another state. The same can’t be said about attacks by nuclear powers against non-nuclear states.

Indeed, this argument was laid out quite nicely three years ago by Des Browne, the UK’s then-Secretary of State for Defense, in a speech to King’s College:

Why do we need a nuclear deterrent?

The answer is because it works. Our deterrent has been a central plank of our national security strategy for fifty years. And the fact is that over this fifty years, neither our nor any other country’s nuclear weapons have ever been used, nor has there been a single significant conflict between the world’s major powers. We believe our nuclear deterrent, as part of NATO, helped make this happen.

In the same speech, he asked, "Are we prepared to tolerate a world in which countries who care about morality lay down their nuclear weapons, leaving others to threaten the rest of the world or hold it to ransom?" Quite obviously, the answer is No.

A World Without Nuclear Weapons

The obvious retort, then, is that we maintain nuclear weapons only because others might use them against us. So why not rid ourselves of these weapons entirely?

The Europeans seem very enthusiastic about President Obama’s Prague nuclear disarmament speech of last April, in which he promised, "The United States will take concrete steps toward a world without nuclear weapons." While most Americans likely took that as rhetorical throat clearing, what with the difficulty of uninventing 60-year-old technology. (Indeed, Obama acknowledged that "This goal will not be reached quickly –- perhaps not in my lifetime.") Europeans apparently see that as a legitimate goal. Indeed, one parliamentarian announced that "no sane person" would disagree with it.

Aside from poisoning the well, a tried-and-true debating tactic, is that really true?

At first blush, it sounds like a wonderful idea. After all, nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction that can kill innocents by the thousands if not the millions. Who wouldn’t want to be rid of them? Getting to that point might be absurdly fanciful from a practical standpoint, but it’s a wonderful ideal, no?

Certainly from an American standpoint it is. By most estimates, we spend more on defense than the rest of the planet combined. A nuclear-free world would be one in which our conventional military might would give us even more freedom of action than we now enjoy. North Korea would be rendered a minor irritant and our relationships with Iran and Russia would improve decidedly in our favor.

Presumably, the same is true of the Western Europeans and the NATO countries, who would be far less constrained in their relations with Russia and far less worried about Iran.

But the opposite would seem obviously true as well. Surely, North Korea and Russia are much happier as nuclear powers. And there must be some reason Iran is so actively pursuing nuclear capability. There are decided advantages to being a member of the club.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council.

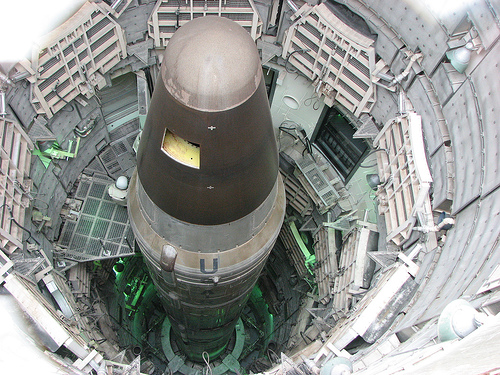

Image: nuclear-ICBM.jpg