With new leadership shaking up Ecuador’s politics, the country has joined many of its neighbors in a renewed battle against corruption at the highest levels of government. In early August 2017, Ecuador’s President Lenín Moreno used an executive decree to strip his Vice President Jorge Glas of all his powers. Moreno’s measure—aimed at neutralizing Glas, rather than ousting him—resulted from growing disagreements with the vice president, who is enmeshed in corruption allegations.

With new leadership shaking up Ecuador’s politics, the country has joined many of its neighbors in a renewed battle against corruption at the highest levels of government. In early August 2017, Ecuador’s President Lenín Moreno used an executive decree to strip his Vice President Jorge Glas of all his powers. Moreno’s measure—aimed at neutralizing Glas, rather than ousting him—resulted from growing disagreements with the vice president, who is enmeshed in corruption allegations.

Ecuador’s former President Rafael Correa repudiated Moreno’s move to strip Glas of authority, adding to his long list of criticisms against the new president. Although Moreno was Correa’s handpicked successor—he served as Correa’s vice president from 2007 to 2013, their relationship has turned sour. While Moreno has embraced a national dialogue with numerous political parties and civil society groups —his predecessor’s most bitter rivals included—Correa has accused his successor of a “mediocre” and “disloyal” betrayal. This rivalry has sparked rifts in the ruling party, setting the scene for a political clash that will determine the future of the party and the country.

Ecuador’s regional influence is modest. However, the challenges it faces with regard to corruption reflect major issues Latin America must tackle in the coming years. As the bill for last decade’s aggressive government spending is passed down to new administrations, so is the responsibility of probing corruption in the commodity boom’s investment cycle.

Moreno’s party, Alianza PAIS (AP), the country’s leftist ruling party for the past decade, secured and maintained power amid corruption scandals, economic pressures, and a worsening conflict within its ranks. Correa founded the party and stood at its helm for over a decade. For Moreno, tackling Ecuador’s economic and political challenges might mean going against AP’s core.

Unwavering support from Correa and an arsenal of state resources won Moreno the presidency in April, 2017, albeit by a slight margin of 51-49 percent. Within a deeply divided society, Moreno has sought reconciliation with the other half of the electorate. Since stepping into office in May, he pledged to fight corruption head-on and criticized the past administration for overstating its economic legacy, an unthinkable feat among AP’s membership. All the while, his approval ratings surged to over 70 percent.

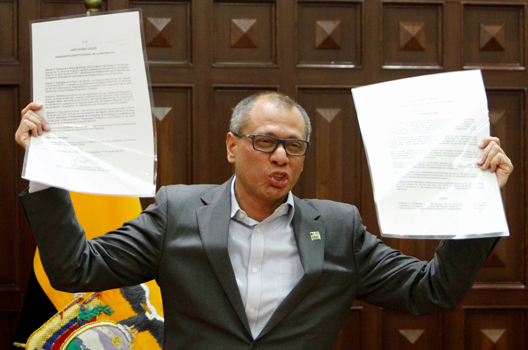

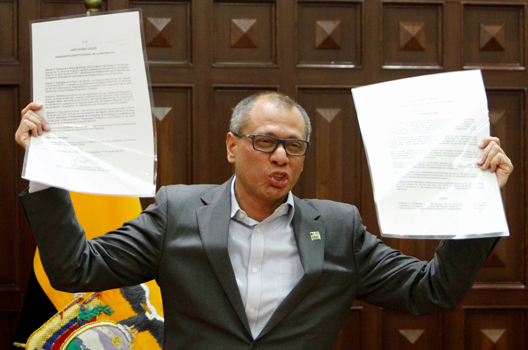

Today, Glas is arguably the most polarizing figure in Ecuadorean politics. To his critics, he personifies the public corruption of the past decade. To his supporters, he represents loyalty to Correa and his “Citizen’s Revolution,” his party’s socioeconomic project and Correa’s political banner. Moreno’s executive order against Glas was lauded by the political opposition and Moreno’s supporters within his party, but appears to be a direct blow to AP’s more militant, pro-Correa factions.

The decision came after Brazilian news outlet O Globo released a recording from the testimony of a former director of construction giant Odebrecht in Ecuador. The tape reportedly implicated Glas, also Correa’s vice president from 2013 until the end of his term, in bribery charges of over $14 million. From 2007 to 2015, the Correa administration granted Odebrecht infrastructure contracts worth over $1.5 billion. Glas is also under investigation for alleged corruption linked to oil contracts and export commitments in state-owned Petroecuador. Former Petroecuador Manager and Hydrocarbons Minister Carlos Pareja Yannuzzelli was extradited on Friday. He is expected to testify to Glas’s involvement in the company’s illicit dealings under a plea bargain.

Glas, who denies any wrongdoing, is one of Correa’s closest allies in the new administration. The former president has defended Glas repeatedly, despite longstanding accusations of graft from Glas’ time as minister of strategic sectors from 2010 to 2012. Correa originally planned to endorse Glas as AP’s presidential candidate, but Moreno’s more favorable public image tipped the balance his way. It was a timely decision for AP to back Moreno, as Glas received vast negative attention and frequent accusations of corruption during the election.

Glas has argued that Moreno’s move against him was a “clear retaliation” for disagreeing with the president, and that he is victim of political harassment. The day before his functions were removed, Glas publicly denounced the president’s proximity to the opposition, the replacement of Correa loyalists in state-owned media outlets, and an alleged manipulation of the country’s economic indicators. Many members of AP, including the party’s executive secretary and Correa himself, continue to back Glas.

Beyond a battle over the control of AP, Moreno’s faction within AP must face off against that of Correa and Glas over Ecuador’s corruption and economic woes.

Glas could become a scapegoat of AP’s crimes, but the fight against corruption does not start or end with him. Several other members of the Correa administration are directly implicated in graft probes.

At the outset of his presidency, Moreno vowed to root out corruption through a comprehensive “surgery.” Caught between reuniting AP and fulfilling his promises to the country, Moreno’s surgical moves against corruption might demand more amputations than his political capital is ready to endure. Ultimately, his success will hinge on safeguarding independent judicial institutions and involving non-state actors to reinforce their efforts.

The economic scenario, in turn, is even more complex, as painful looming decisions have spurred tensions. Despite Moreno’s commitment to keep and expand social welfare gains paid for by the Correa administration, tightening reforms will be necessary to address external pressures and fiscal imbalance. Moreno knows such measures would hurt his base, redirecting some of his support to Correa. In preparation, he has taken superficial actions. Moreno has quarreled with Correa over the country’s debt and economic diagnosis, claiming that he inherited a far less favorable economy than his predecessor had boasted. A recent survey shows that 85 percent of Ecuadorians back Moreno’s efforts to “uncover” the country’s economic reality. Also, Glas’s removal from a public-private council on production, where he had limited credibility, comes as a relief for the private sector. While initial austerity measures and a partial break with production limits set by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) contradict a number of Correa’s milestones, Moreno is unlikely to reverse his predecessor’s popular economic program significantly.

Stripping Glas of his powers is an astute move by Moreno. It also represents a risk. Widespread discontent for corruption makes Glas a desirable enemy for Moreno, but dissent from AP endangers his mandate. He must now avoid backlash from his own camp, while securing support from other sectors that support his move to back away from Correa’s political line. It will be increasingly hard for Moreno to appease both sides. As his party strives for harmony and Correa cements his role in the opposition, the roll out of Moreno’s policies and concrete results are urgent.

Glas could be deposed by political trial or by a vote in the legislative branch. Time will tell whether AP’s legislators are ready to coalesce behind Moreno, against the will of their “historic leader,” to usher in a new era for the Citizen’s Revolution.

Sebastian Maag is an intern with the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. You can follow him on Twitter @ @maag_smaag

Image: Ecuador's Vice President Jorge Glas gives a news conference after he was relieved of his duties by President Lenin Moreno, in Quito, Ecuador, August 3, 2017. REUTERS/Daniel Tapia