Neither of France’s two presidential candidates—Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron—is likely to obtain a favorable majority in the parliament in legislative elections in June. For the first time since the creation of the Fifth Republic in 1958, the president’s party is likely to be a minority party in the National Assembly and the Senate from the start, overshadowed by the leading mainstream parties—currently the Socialists on the center left and the Republicans on the center right. Hence, the campaign promises made by Macron and Le Pen are already in jeopardy.

Neither of France’s two presidential candidates—Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron—is likely to obtain a favorable majority in the parliament in legislative elections in June. For the first time since the creation of the Fifth Republic in 1958, the president’s party is likely to be a minority party in the National Assembly and the Senate from the start, overshadowed by the leading mainstream parties—currently the Socialists on the center left and the Republicans on the center right. Hence, the campaign promises made by Macron and Le Pen are already in jeopardy.

In the French political system, the president shares power with the prime minister. Although the president may nominate someone for that office, the prime minister needs the support of the majority of the National Assembly in order to form a government. It is possible that France will expect some form of coalition or “cohabitation”: a president from one party and a prime minister from an opposing party that has a parliamentary majority.

Thus far, there have been only three cases of cohabitation: two under President François Mitterrand (a Socialist), and one under President Jacques Chirac (a neo-Gaullist whose party is now called the Republicans). In all three cases, one or the other of those two parties had a majority in the National Assembly. But in 2017, the situation is more complicated. Neither Le Pen’s far-right National Front nor Macron’s recently established En Marche! (On the Move!) is likely to come anywhere close to capturing its own single-party parliamentary majority. This likelihood raises a crucial question that the media and the candidates themselves have been avoiding: how will Le Pen or Macron be able to govern?

In France, the president is an important figure but has a limited power in national politics. In addition to nominating the prime minister, the president has the ability to hold a referendum and seize exceptional powers through Article 16 of the constitution if the country is under great threat. These are critically important powers under the current circumstances. For instance, Le Pen wants to hold a referendum on France’s membership in the European Union (EU) which could lead to a French Brexit or “Frexit,” and the state of emergency imposed by French President François Hollande following the November 2015 terrorist attacks still prevails. However, the president’s true power resides in his international prerogatives, which enable him to negotiate international treaties and directly ratify them through a referendum or in parliament.

If the president wants to gain significant legislative power to implement reforms, he or she needs to govern with the parliamentary majority. If the major party in parliament is the same as president’s, then all the powers converge. However, if this is not the case, the president can create a state of cohabitation by appointing a prime minister from the majority party in order to break the deadlock.

Although the French people will vote for their parliamentary representatives on June 11 and 18, the anticipated results are already historic. Indeed, neither Macron’s nor Le Pen’s parties have ever gotten the majority in parliament. Le Pen’s National Front currently has only two deputies in the National Assembly, while Macron does not even have one elected representative in the parliament because his party was only recently created. Also, even though Macron has an advantage over Le Pen as multiple political figures within the Republican and the Socialist parties have been supporting him during the second round of the presidential election, it will not be the case during the legislative elections and getting a majority under his own banner will be a challenge. Thus, both candidates face a particularly adverse situation.

The legislative elections are set a month after the presidential election precisely to give the president all the necessary cards to govern properly. Interestingly enough, these elections are local ones where the members of parliament are often re-elected and where the two main parties have deep ties with members of their communities. Moreover, a significant number of older members of parliament will not run for another term in the coming elections. As a result, Le Pen could get many representatives but a majority is hardly conceivable as her network rapidly falls short.

On the other hand, Macron must build his legislative campaign from scratch with less than two months to organize. Additionally, because he promised that he would present one official candidate for every seat available, he needs 577 candidates to run under the En Marche! banner in the legislative elections, and 289 to win a parliamentary majority.

Hence, the National Assembly seems compromised for Macron and Le Pen and the Senate is even more problematic. Obtaining a majority in the Senate is always challenging, but currently Le Pen and Macron are not even represented in this chamber. Their chances of getting a majority are minuscule as there is no direct voting from the people: 48 percent of the Senate is filled by proportional representation while the other 52 percent is indirectly elected. Although it is important to note that the Senate does not hold as much power in France as it does in the United States, neither of the candidates seems to have adequate resources to get a Senate majority, or even a majority coalition with friendly parties.

The new president will have to work with the majority in the parliament or, if there is no majority, form a multiparty coalition government. As a centrist, Macron will be able to form a coalition with both the center left or the center right, if necessary. However, if Le Pen wins on May 7, she will face an extremely antagonistic parliament.

So, what can they realistically do? Both Macron and Le Pen will be able to keep their foreign policy promises. In other words, Le Pen would be able to negotiate treaties with the EU, and even submit a referendum to leave the Union, while Macron could try to improve the integration of France into the EU.

On the national level, Le Pen is in a delicate position. She will not be able to form a coalition if she does not have a majority. The Republican and Socialist party leaders who did not make it to the May 7 runoff— François Fillon and Benoît Hamon, respectively—have called upon the French people to vote for Macron to prevent Le Pen from winning. Thus, assuming that she will not obtain a parliamentary majority, Le Pen will appoint her own government that will not be supported by the parliament. On the other hand, if she chooses to appoint a government from the majority, she loses all control. Le Pen recently announced that she would name a government from her party if elected, risking a five-year stalemate.

Macron, however, is in much better shape because his diverse support will allow him to create a coalition. But the Republicans and the Socialists are not planning on doing him any favors and his plan to balance left and right could rapidly destabilize him.

The candidates must choose between losing their power under cohabitation or controlling the government and dealing with an adverse parliament. The ability of Macron or Le Pen to govern smoothly thus already appears compromised.

Alexandre Aubard is the founder and president of the European Horizons chapter at the George Washington University. European Horizons is a student-run think tank focused on the European Union and transatlantic relations. He is currently a senior at the George Washington University studying international affairs and economics.

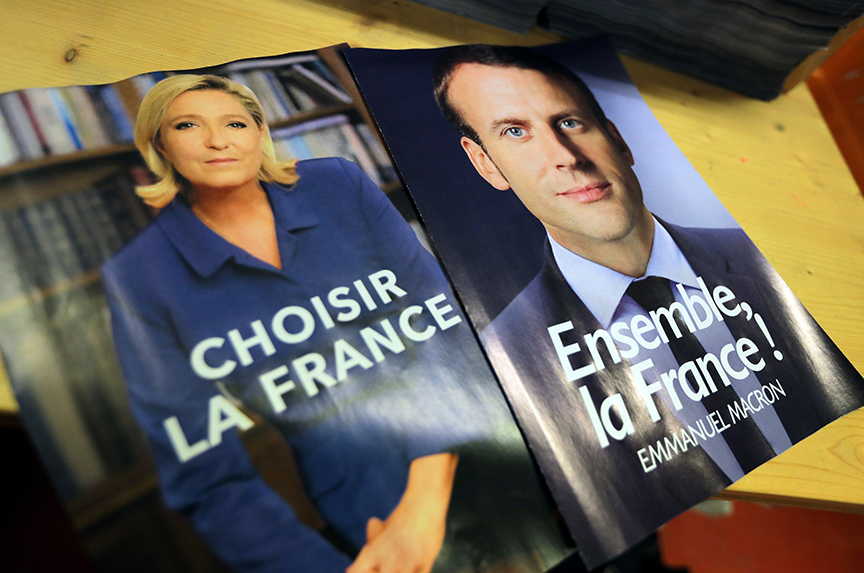

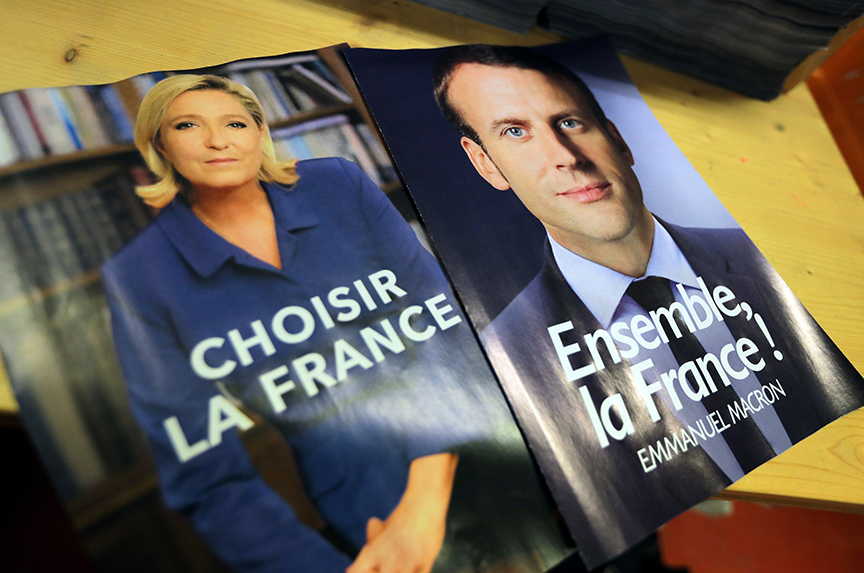

Image: Electoral documents for the May 7 runoff in the French presidential election, which pits En Marche! candidate Emmanuel Macron (right) against the National Front’s Marine Le Pen (left), are displayed in Nice, France, on May 3. (Reuters/Eric Gaillard)