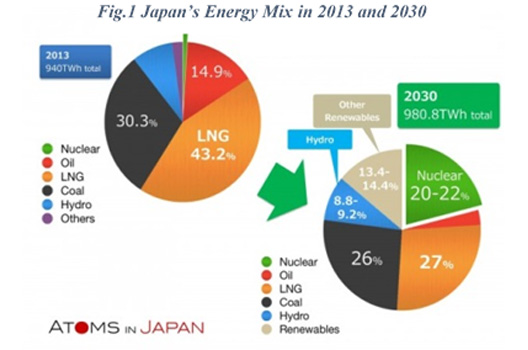

In June, Japanese energy officials released an eagerly anticipated draft report outlining plans for the country’s 2030 energy mix. Here’s the proposed breakdown:

In June, Japanese energy officials released an eagerly anticipated draft report outlining plans for the country’s 2030 energy mix. Here’s the proposed breakdown:

The Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry’s (METI) draft report is worth studying not just as a government estimate but also as an indicator of official intent. The numbers showcase three critical dynamics that will shape Japan’s energy strategy for a post-Fukushima world.

1) Nuclear power has a future in Japan—but perhaps not as bright as the government predicts

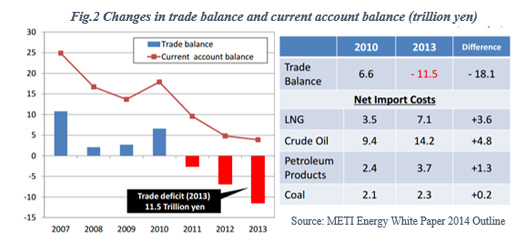

Nuclear power production ground to a halt between 2011 and 2013 after Japan chose to shut down all forty-eight of its working reactors. This decision carried steep opportunity costs. Rising imports of expensive crude oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) produced Japan’s first trade deficit in thirty-one years and added an additional $100 billion (9.9 trillion yen) to the record deficit in 2013. What’s more, household electricity bills rose 20 percent on average due to the greater costs of imported oil and LNG.

METI’s 20-22 percent target for nuclear energy reflects Japan’s desire to reverse these trends. Cheap, stable, domestically produced energy would breathe much-needed life into an ailing Japanese economy and deflate its swelling negative trade balance. This attractive future is intuitively appealing.

Nevertheless, the METI draft errs when it glosses over the political and practical challenges of renewed nuclear production. These are not insignificant.

For one, the politics of nuclear restarts are divisive. Though nuclear restarts enjoy robust support at the local level—especially in towns where nuclear plants supply much-needed jobs—they meet stiff opposition at the national level. Indeed, recent national polls show 60 percent opposition to any nuclear restarts. Japanese politicians risk angering a sizable share of the electorate by pursuing nuclear restarts on a broad scale.

But while public opinion may shift in time, practical hurdles remain. Achieving the 20-22 percent target requires Japan to not only restart thirty of its existing reactors, but also to extend the lifetime of aging reactors currently set for retirement. This will be a difficult, uncertain, and politically fraught process. New safety regulations enacted in the wake of Fukushima could even render life extensions cost-prohibitive in many cases. Ultimately, these factors lead independent analysts to conclude that nuclear energy will supply no more than 10 percent of Japan’s energy in 2030, a sharp divergence from official numbers.

2) Energy security is the highest priority

Counting hydro, nuclear, and other renewable power together as “domestic” production, Japan’s self-sufficiency rate—domestic energy production as a percentage of total energy consumption—aims to reach 45.6 percent in 2030. This is a much-needed improvement over the status quo: a shockingly low 6 percent.

The renewed emphasis on energy security comes as Japanese policymakers reassess their prioritization of risk. Preventing another Fukushima, while certainly important, is no longer Japan’s primary objective. As Nobuo Tanaka, a former Executive Director of the International Energy Agency, explained in an interview with the Wall Street Journal:

“A crisis in Iran or the Strait of Hormuz could happen much more frequently than once every 1,000 years, like the tsunami…We have to prepare for that kind of emergency.”

The energy mix proposed for 2030 reflects this analysis. Shrinking crude oil’s share—from 14.5 percent to less than 4 percent—will necessarily reduce Japan’s reliance on the Gulf, especially since 81 percent of Japan’s crude oil imports currently pass through the Strait of Hormuz. While only 25 percent of Japan’s LNG imports come from the Gulf, this is no chump change; it represents roughly 10 percent of Japan’s current energy demand. Aggressively courting new suppliers like the United States and Russia will also help Japan insulate itself from supply disruptions over the medium to long-term.

3) Japan will choose cheap and secure energy over expensive, cleaner renewable fuels.

At first glance, the 26 percent share allotted to coal by the METI draft report may seem strange. It stands in sharp contrast to the United States and European nations, which aim to eliminate coal from their respective energy mixes. However, coal offers three advantages uniquely tailored to Japan’s needs: low prices, stable suppliers, and political backing.

Coal is cheap. And despite the recent plunge in oil and LNG prices, it still holds a comparative price advantage over both fuels. Japan’s recent experience with trade deficits and pricey LNG and oil imports only accentuates this contrast. It gives cheap and dirty coal an attractive sheen.

Second, coal offers a distinct energy security advantage: avoiding the Middle East altogether. Eighty percent of Japanese coal imports come from Australia and an additional 9 percent come from Indonesia. Both countries provide Japan a secure source of energy, free from the geopolitical risk that tars Gulf petro states. This long-term stability is invaluable.

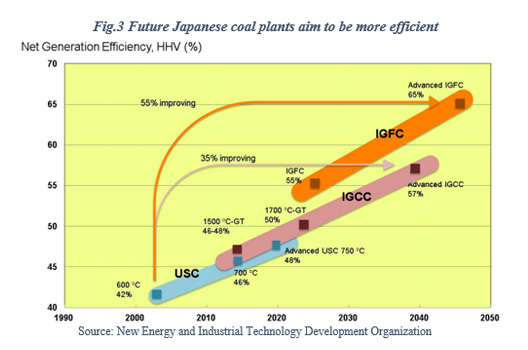

Third, Japanese officials strongly believe they can leverage new technologies to blunt the environmental costs of coal. A key priority is increasing the heat efficiency of coal thermal power generators. Energy officials intend to deploy new thermal generators, like the “integrated coal gasification combined system,” (IGCC) that would push heat efficiency rates upwards from 42 to 57 percent. The most advanced generators would yield heat efficiency rates of 65 percent and a 30 percent decrease in related carbon emissions. Government commitment to these technologies secures coal’s lasting place in Japan’s energy mix.

Japan’s ambitious vision requires skillful execution

METI’s proposed 2030 energy mix is a welcome course correction to a shortsighted status quo. The new goals are remarkably ambitious and, if achieved, will tangibly strengthen Japanese energy security.

Of course, the road ahead is filled with stumbling blocks—particularly with respect to nuclear restarts and life extensions. Navigating these obstacles requires Japan to clearly articulate the energy security and economic rationale undergirding the draft report. Framing the issue in these terms—pointing out 20 percent higher electricity bills and instability in the Middle East—will ease the transition to a sound energy strategy.

Anand Raghuraman is an intern in the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center.

Image: A banner reading "Stop Restart" is displayed at a protesters' camp site near Kyushu Electric Power's Sendai nuclear power station in Satsumasendai, Kagoshima prefecture, Japan, July 8. Kyushu Electric Power Co. started loading uranium fuel rods into a reactor in July marking the first attempt to reboot Japan's nuclear industry in nearly two years after the sector was shut down following the 2011 Fukushima disaster. (Reuters/Issei Kato)