For Ukrainians, the war in eastern Ukraine has become an everyday reality. Only two years ago, though, no one in the country believed war was possible—and certainly no one expected that propaganda would be one of its main weapons.

For Ukrainians, the war in eastern Ukraine has become an everyday reality. Only two years ago, though, no one in the country believed war was possible—and certainly no one expected that propaganda would be one of its main weapons.

Since Ukraine’s independence in 1991, little attention was paid to building a system that would ensure the security of information: that is, that would actively counter false propaganda. State security services ignored even the most basic anti-Ukrainian messages.

As a result, when the new government was faced with aggressive propaganda, it appeared completely incapable of acting. State functions related to information security were divided between at least seven different agencies and ministries. There was no proper coordination between these bodies, their functions were often duplicated, and some important tasks were not implemented at all. There was no state unit responsible for monitoring the situation in the field or identifying threats, which made simple decision-making impossible. Furthermore, there were no clear mechanisms for implementing such decisions.

During that time, Crimea was lost, and residents of the Donbas were frightened by Russian propaganda and believed that “fascists” were coming to kill them. Something had to be done to limit the onslaught of propaganda.

Staying Democratic

Many societies have had to bridge the dichotomy between security and democratic values. This quandary arose for the United States and the West after 2001. Ukraine has faced a similar dilemma in its search for solutions to its propaganda-related problems.

The first solution was the easiest: to limit the broadcasting of Russian TV. Quite popular among Ukrainian audiences, it became a constant and aggressive source of lies and hatreds, combined with a glorification of Stalinism and other attributes incompatible with democracy.

When Kyiv responded, Russian media accused it of violating freedom of speech. But that was not the case: Ukrainian authorities referred properly to national and international norms, and the legitimacy of this decision provoked no genuine doubts. Five Russian channels were initially banned in March 2014, and the state media regulator then began to tightly monitor the content of Russian channels; by December 2015, the list of banned channels included twenty-five titles.

The next step was to limit the share of Russian films on Ukrainian television channels; on some days, these could constitute up to 87 percent of content. As these films (especially those produced recently) often had elements of Kremlin propaganda, Ukrainian experts considered them another weapon in the ongoing infowar. In March 2015, a law was issued prohibiting television broadcasting of Russian films that either had been created after January 1, 2014, or glorified the Soviet regime, or Russian militarism. This decision also caused protests in Moscow, but both Ukrainians and the European community understood the need for these measures.

All of these limitations only concerned broadcasting via air or cable; Ukrainians still have access to Russian television and films through satellite and the Internet. Nevertheless, the effect of the measure has been evident. Telekritika reports that before the war, 22.7 percent of Ukraine’s population watched news on Russian TV; by June 2015, this share had decreased to 12 percent. The share of Russian-made films on Ukrainian television decreased by almost three-quarters.

Another important decision occurred in October 2015, when Ukraine’s parliament adopted a law obligating broadcasters to report on their owners and beneficiaries. In Ukraine, the “oligarchization” of media and its nontransparent ownership made it a strong tool to manipulate public opinion, and a particularly dangerous one when central media connected with pro-Russian business interests to promote Russian propaganda.

But no single media outlet has been particularly oppressed because of its pro-Russian orientation. Even the most obvious agents of Kremlin propaganda continue operating, though one journalist has been arrested for conducting anti-mobilization agitation. The government’s position has been opposed by some right-wing media and politicians, who demand firmer actions to restore security, but the government says it will undertake no action that could be viewed as a violation of freedom of speech.

Ministry of Ineffectiveness

The decision to establish a Ministry of Information Policy in December 2014 was met with strong resistance inside Ukraine and confusion abroad. Both national and foreign analysts considered it to be an instrument of state censorship. These fears have not been realized. The new agency has been too weak to apply pressure or any other influence on media, and its real impact and purpose remain obscure.

The Ministry didn’t push for changes in legislation that required significant corrections to improve information security. The Ukraine Information Security Concept, recently drafted, is a rather doubtful achievement: the OSCE has sharply criticized it, while domestic experts have proved that the document cannot be the basis of further policy in the field. The Ministry has also launched some patriotic communication campaigns, including online and outdoor campaigns titled “Crimea is Ukraine” and “Defending Ukraine,” but they are not enough to be considered “ensuring informational sovereignty.”

Phantoms Spread

At the same time, the situation remains extremely dangerous. Despite the bans and restrictions, Ukrainians still have access to Russian television channels and films. Meanwhile, the Kremlin uses social networks to disseminate phony and manipulative messages, and a number of influential Ukrainian media affiliated with pro-Russian business transmit “softer” propaganda.

All of this propaganda has been quite effective. According to Telekritika and KIIS polling, 42 percent of people in Ukraine’s south are convinced that the events on the Maidan were a violent seizure of power; 28 percent believe that Ukraine is at war with its own population in the east.

Meanwhile, the propaganda has evolved. Increasingly it aims not only to spread “Russian myths” (for example, fakes about Kyiv Nazis and crucified boys) but also to seed instability and hatred within Ukrainian society. For example, 60 percent of Ukrainians admit they have a negative attitude toward internally displaced people, but only third have had any actual contact with them. It is likely that such prejudice is conditioned by negative discussions in the media. Efforts have been detected to destabilize other interethnic and interreligious relations in Ukraine as well.

The government appears helpless in a situation like this. It seems unable to produce a single national narrative that could oppose Russian myths, and even if it could, the government has no tools with which to spread it. Moreover, there are doubts whether the government has a clear understanding of what’s going on in society—which is to be expected, given that monitoring and analysis are still absent.

Consequently, at the moment, nothing is being done to overcome the stereotypes and fears cultivated by propaganda; nothing is being done to prevent hate speech in the media or to remove the growing barriers between different social groups. The government and the President have little communication with the public about the conflict, and the vacuum is filled by suggestions, fears, and propaganda.

Only nongovernmental organizations are actively trying to combat propaganda in Ukraine; they aim to monitor trends, reveal fake messages, and develop recommendations. Sometimes they gain support from Western donors and governments, but because they are not coordinated, they largely produce a cacophony with little impact. Instead, emotions and fears continue to rule the game, ensuring favorable conditions for phantoms to continue spreading.

Roman Shutov is Program Director of Telekritika, a Kyiv-based NGO.

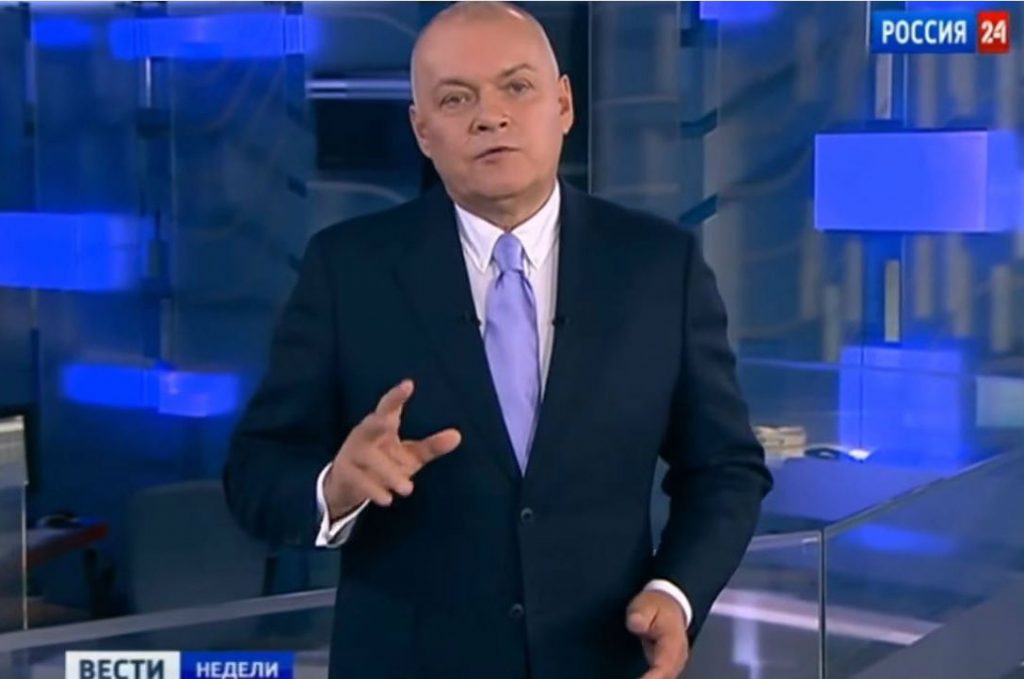

Image: Russian journalist Dmitry Kiselyov hosts Vesti Nedeli on November 4, 2013. Courtesy Screen Shot