Russia remains, in ‘Churchillian’ terms, an enigmatic mystery. In its post-Communist transition to a modern state, Russia has shed most of the impedimenta of Communism and begun to search for new directions. But the old conflict between “Slavophiles” and “Westernizers” has emerged in the streets in a new guise and the outcome remains uncertain.

Although Putin has secured a third term as President, it would be an exaggeration to say that he has and will have sole command of Russia’s future. But it would be an equally serious mistake to underestimate his influence.

Putin has chosen to deal with the emerging forces on Russia’s streets in a careful and balanced way. The middle classes and those who joined them from what used to be the proletariat were greeted with the twin policies of co-option and intimidation. By herding through intimidation at the same time as absorbing through co-option, he clearly intends to keep a tight rein on change and new initiatives, working pragmatically with whomever he believes can help him manage a new and changing state.

The future will not bring a return to the Putin state of full authority, or vlast, of the early 2000s, with near-dictatorial powers where and when he needed them. Public demonstrations pose a continuing challenge that he will be hard put to deal with. At the same time, however, he has shown that he commands popularity, despite concerns over the fairness of the March 4th elections. His priority now will be to prevent Russia from moving in ways that weaken his control and challenge his authority on key issues.

The most important issue affecting Russia’s domestic policy is corruption. It also remains the most untouchable. Some years ago, Putin publicly recognized the importance of working to end corruption. But he also frankly and openly admitted he could do little to make the change. This has led analysts to believe that even Putin does not have full and unfettered control of the country in this area. It may indicate that he remains beholden to some of his subordinates because he and they participate jointly in murky “deals.”

In its relations with Russia, the U.S. has the opportunity to take the initiative on a number of key issues.

First, talks on cooperative ballistic missile defense should be reopened. Significant changes in Russia-U.S. relations already resulted from the 2009 move to negotiate a ‘New START Treaty’ on nuclear-weapons and delivery-vehicle reductions. While the New START cuts were relatively small, they reflected an effort on both sides to achieve a win-win outcome. Since then, the BMD talks have stalled because of Russian fears that our Ballistic Missile Defense System will destabilize Russian deterrence. Moscow’s requests for a treaty guarantee or even a right of veto over use of the system have been rejected by the U.S. on the grounds that a treaty guarantee would be unlikely to be ratified by the Senate, while the proposed right of veto has raised concerns about Russia blocking missiles use against the other states for which the system has been configured, North Korea and Iran.

With the presidential elections in both Russia and the United States out of the way, it is time now to look for a way forward.

Possible technical and practical solutions to the stalemate that could not be put on the table during the US and Russian election campaigns may help to provide a solution. These could include possible greater clarity about current U.S. plans and a clear exposition of future U.S. plans. A second opportunity comes with a possible further stage of nuclear disarmament. In both the U.S. and Russia, experts have begun to look at a new lower limit of 1,000 operational weapons and related delivery vehicles, down from 1,550 under New START.

Some are also suggesting moving the entire delivery force to single warheads. Two related steps have also been suggested: to eliminate most or nearly all of the 4,000 “reserve” weapons and those in re-work or undergoing dismantlement on the US side and a larger number on the Russian side; and to try for the first time to combine limits on tactical weapons with freedom to mix within the proposed overall 1,000 limit.

In parallel, we should consider removing all remaining tactical weapons from close to the former line of confrontation in Europe. Russian tactical weapons, should Moscow wish to preserve them, might be stationed east of the Urals. U.S. tactical weapons could be eliminated or returned to the continental United States. This would require great care in dealing with our European allies. Many see such nukes as an essential part of the linkage of U.S. nuclear forces to NATO defense and deterrence and have been assigned a role in delivering tactical weapons under NATO war plans.

Thirdly, we now face a broad set of opportunities to deal with old or festering issues that sour our relations with Russia. These include differences left over from the fall of Communism in the North Caucasus and along the Ukraine border in Moldova; arguments over the four disputed Kurile Islands with Japan; and arrangements between Russia and NATO over a more robust partnership to deal with European and extra-regional issues as well as closer trade and economic cooperation, which could make progress if Russia moves forward with reforms at home.

Predicting Putin is very hard. He keeps his cards very close to his chest. But my sense is that his pragmatic tactics for staying on top and the opportunities outlined above will move him toward gradual change and an improvement in our relationship. We will see a Putin using co-option more and intimidation less. Or if he uses the latter, he will seek to do so in support of further positive change within Russia and with its friends and neighbors, as well as, possibly, even with its enemies.

Thomas R. Pickering is an Atlantic Council Board director and former under secretary of state for political affairs. During a four-decade career in the U.S. diplomatic service, he served in numerous ambassadorial posts, including as U.S. ambassador to Russia. This piece is taken from the Atlantic Council publication The Task Ahead: Memos for the Winner of the 2012 Presidential Election.

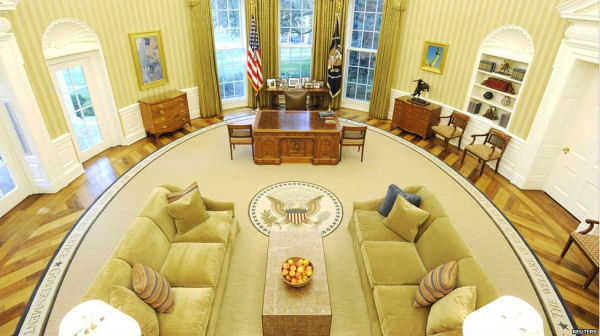

Image: oval-office-2010-new-overview.jpg