One reliable Washington axiom is: When ideologues of the Left and Right agree on a policy idea, hold on to your wallet.

The same folks who told you Iraq would unleash a democratic tidal wave in the Middle East have joined hands with their corresponding numbers on the Left (who turned a food relief mission in Somalia into a hunt for warlords and gave us Haiti as “humanitarian intervention”) to offer a superficially appealing idea: a League of Democracies as an organizing principle for international relations.

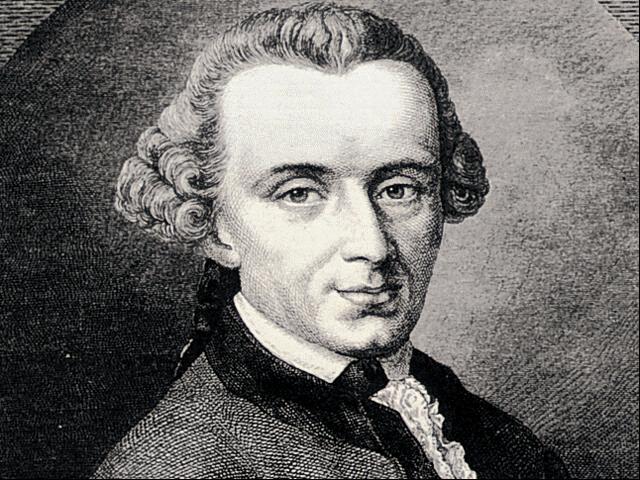

This is, of course, hardly a new idea. The intellectual godfather of this notion is Immanuel Kant, who two centuries ago propounded the theory that the spread of republican government and trade would lead to a future of “Perpetual Peace.”

First proposed by Obama advisor Ivo Daalder in a 2006 National Interest piece (also by the Princeton Foreign Policy project which included many Obama advisors), a Concert of Democracy would be the flagship of a post-Cold War internationalism. In theory, such a grouping would unite Western nations with democracies such as Chile, Peru, and South Africa, all on the basis of shared values. This, it is argued, would provide a new legitimacy for global action in defense of liberty and human rights when the next Rwanda-type crisis arises. The Republican version, put forward by McCain advisor Robert Kagan, calls for a League of Democracies, an idea that made its way into John McCain’s major foreign policy speech.

We saw similar Left-Right convergence over intervention in the Balkans in the ‘90’s. While Kagan ends up in the same place as Daalder, he is less concerned about moral legitimacy (which is seemingly, for neoconservatives, never in doubt) and more focused on countering what he sees as a rival ideology challenging the “freedom agenda.” While Kagan would argue that such a grouping could provide legitimacy outside the UN for future American interventions, it would inevitably be seen as an illegitimate. To his credit, Obama dismissed this as a bad idea in a July CNN interview, but in Washington, no policy debate is ever really over.

Kagan posits that “Ideology matters again.” What does he mean by this? That Russia and China are autocratic great powers and that they thus embody an anti-democratic ideology: they “believe in autocracy.” This contrary approach to governance, he suggests, will propel them into confrontation with the world’s Democratic Great Powers, and presumably challenge the global system, of which the U.S. is at the center.

But is this so? I will be the last one to defend the oil and gas Soprano state that Vladimir Putin runs. But is there really an ideology other than belief in a strong central government and staying in power that guides Russia, and for that matter China? (For that matter, how do you explain Putin’s 70% popularity ratings?) Do they present themselves as alternative models they seek to export? Are they destined to challenge the global system? Are they incompatible with Western democracies?

“American and European policymakers say they want Russia and China to integrate into the international order,” according to Kagan, “but it is not surprising if Russian and Chinese leaders are wary.” Huh? What planet does he live on? Deng Xiao-peng bet China’s future on integrating into the world economy three decades ago. And China has moved increasingly in that direction ever since. The list of norms and regimes that Beijing subscribes to (however imperfect its implementation) from the WTO to the Nuclear Suppliers Group to the ICAO is an exhausting one. Russia is a bit more complicated. Its complex energy supplier relationship with Europe and globally as a major oil producer and thus also investro gives it a large stake in the global economy. This contrasts with the USSR, where it created a wholy separate economic system in COMECON. Yet, as its invasion of Geogia demonstrtes, Russian bitterness at the collapse of the USSR, and its attempt to restore dominance in much of the former Soviet Union, underscores its revisionist appeal.

Kagan is partly right. Ideology is back. But it is that which he and his Democratic soul-mates represent, not theirs. Neither China nor Russia offer themselves up as models to be emulated or exported. (And frankly, if oil were $40 a barrel a number of autocratic states from Venezuela to Iran would not be viewed by anyone as models of authoritarian development.)

Behind his logic is the converse of what ideologues accuse foreign policy realists of. The neocon critique holds that realists’ fallacy is that all states seek to maximize their power and the internal character of a state does not matter. Thus the neocon mission civilatrice is to spread democracy and rid the world of non-democratic regimes. The liberal version is animated by a desire to rise above mere national interests and stand for humanitarian values, redefining internationalism in the post-Cold war era.

This illustrates the dangers of being half right. This argument has a point in that the internal character of regimes does tend to be a factor in a nation’s foreign policy. But non-democratic regimes also have interests. Other factors such as geography, culture, ethnic minority interests, and economics are also part of their calculus. They can and do play by international rules if they judge that is in their interest.

Neocons and liberal idealists make a mirror-image mistake that they accuse so-called realists of: that the internal character of a regime is the defining factor of its foreign policy. If this were true, how could we have made all those agreements with the Soviet Union, or China, or for that matter, Egypt and Saudi Arabia? This logic leads to the answer to every problem on the right being “regime change” since we cannot do business with them. North Korean nukes? Iran’s proliferation? No point to diplomacy — just get rid of the offending regime. And on the left, using force to rid beleaguered nations of nasty, cruel regimes. As we have found out in Iraq, however desirable it may seem in theory, in practice in the real world, regime change often comes at a very high, if not unbearable cost.

On the other side of this fallacy appears an assumption that seems to unite the Left and the Right: that Democracies share values, and somehow either do not have national interests or have identical interests. This is where Kagan’s logic ends up and intersects with Daalder’s, and why he is so troubled that authoritarian capitalist states seem to be able to prosper – at least for a while.

Sorry, Charlie. This is an idea, as George Orwell once said, “so dumb only an intellectual could believe it.” Of course, it would be preferable if democracy were universally practiced. And Winston Churchill was correct that “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” But even if you posit that democracy is a universal value that will ultimately prevail, that does not mean that in any given time or place it is possible or that it defines what a nation’s interests are.

We still live (more or less) in the Westphalian world of nation-states. States have interests, however much their internal political dynamics may shape how they pursue them. Just think back to the Iraq debate and the views of many of our Democratic European allies. What sort of world order would there be if we defined China, poised to become the world’s second largest economy, and Russia, the world’s largest energy exporter, out of it? Not to mention all the Middle East oil exporters.

And it is illusory to think that simply because they are democracies, Indians (their Burma policy is a good example) or Latins share a collective sense of obligation to act in any given situation. In fact, many non-Western democracies, India and Peru, for example, are very reluctant to”name and shame,” let alone to feel obliged to intervene by a “duty to protect” at the expense of others’ sovereignty. And then there is the non-trivial issue of defining who is a democracy, sure to rankle many who don’t make the cut.

Old fashioned as it may be, the notion of a balance and concert of major powers as an important underpinning of world order still has much to be said for it. Of course, American foreign policy must balance hardcore national interests with our entrenched values, but each case must be judged on its merits. More democracies being part of an international community would be desirable, and this is certainly one of the strengths of the transatlantic and US-Japan bonds. But do we believe that unlike most other successful Confucian cultures in East Asia, China will be impervious to pluralistic government over time? Or that Russia will coast on a sea of petrol forever? In the meantime, we should have learnt by now that it is difficult to jumpstart history and often leads to disastrous unintended consequences.

If we believe our democratic values are indeed universal, then we should have the wisdom to let historical forces play out in each nation’s own circumstances. Knowing when to hold’em and when to raise the ante is key to successful democracy promotion.

The search for easy answers in a very untidy world is understandable. But to paraphrase Don Rumsfield, you manage international relations in the world you have, not the one you would wish for.

Robert Manning is a Senior Advisor to the Atlantic Council. The views here are solely his own, not those of any U.S. government agency.

Image: immanuel_kant-democratic-peace.jpg