The Russian-led conflict in eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region and the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany are the two most contentious issues on the Euro-Atlantic security agenda today. Each is at a dangerous impasse. Linking the two would broaden the space for negotiation and provide opportunities for potential trade-offs. This could lead to a resolution that would be in the interest of all parties.

The alternative is clear: a perpetuation of conflict. Russia is currently deploying more troops to its border with Ukraine. Efforts through the Minsk and Normandy processes to restore Ukrainian sovereignty over occupied east Ukraine have utterly failed. There is no prospect on the horizon for an end to the violence that has claimed an estimated 14,000 lives thus far.

US sanctions on Nord Stream 2 (NS2) have been effective to date in delaying completion of the project, but they do not come cost-free. Rather, they come at the price of straining US–German relations at a time when such ties need to be rebuilt. And, of course, NS2 sanctions also do further damage to US relations with Russia.

There may be opportunities for a new approach. Revulsion in Germany over the poisoning and imprisonment of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny has cast a shadow over NS2. This leverage will not last forever. The best place to deploy it is not in stopping NS2, whose harm to European energy security, thanks to concerted efforts by the EU and key partners such as Poland, has diminished in recent years. Rather, the leverage should be used to secure a much more important aim: Russia’s withdrawal from eastern Ukraine.

There would, of course, be no war in eastern Ukraine without Russian instigation. Russian forces have no right to be there. But there they are. And there they will stay until the Kremlin determines it is in its interests to withdraw them. Nothing proposed thus far outweighs the Kremlin’s desire to maintain its hold on the Donbas region as a pressure point on Ukraine. Putting NS2 on the table could change that.

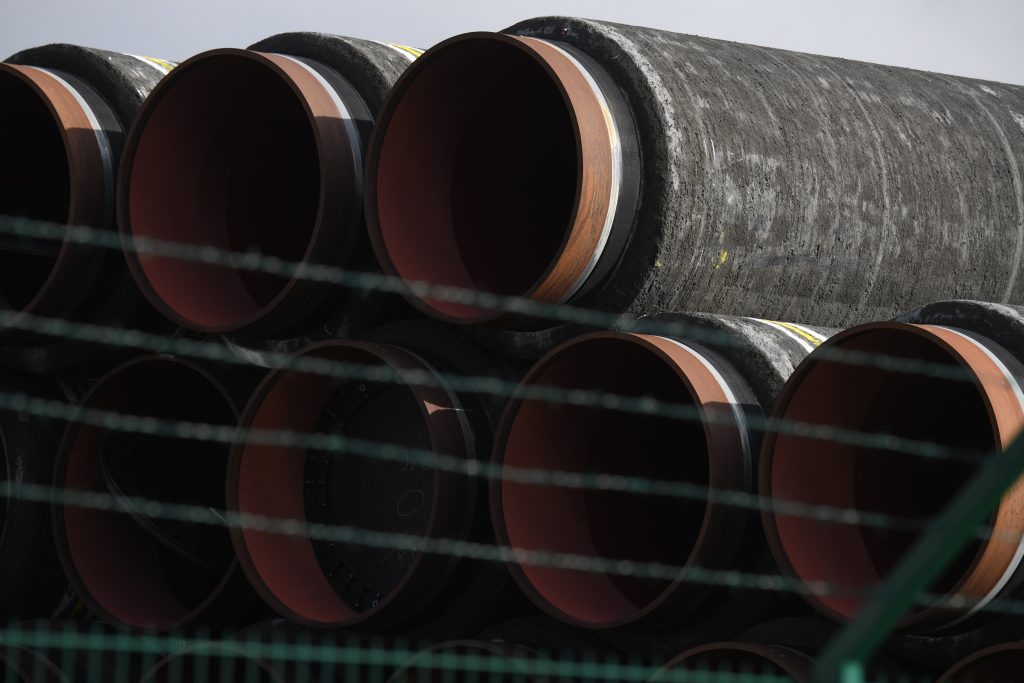

NS2 is a prestige project for Putin. German relations hold a special place for him. It is hard to imagine the Kremlin not doing everything in its power to avoid the prospect of dismantling eleven billion dollars worth of NS2 pipe now in the Baltic.

Yet NS2 is not a done deal, despite being 95% completed. Even if Gazprom were able to circumvent sanctions and finish construction late this year as it intends, broader US sanctions imposed in December 2020 could, if enforced, block insurance and certification that would enable gas to actually flow.

NS2 has until now served the Kremlin’s geopolitical purposes by creating a rift between Germany and the US and between Germany and other partners, such as Poland, the Baltic States, and Ukraine. But being in bed with Gazprom is an embarrassment for Germany after the poisoning of Navalny. Furthermore, the Greens oppose the project on environmental grounds and may well be in a position to kill it as part of a future government after German elections in September.

Recently, the European Parliament has again called for an end to the project. Even the French Minister for European Affairs has stated that NS2 could be scrapped as a response to the Navalny poisoning.

Given all this flack, the Kremlin may determine that ending its hold over the Donbas in return for securing agreement to allow NS2 to operate would be in its interest. NS2 is now poisoning Russian relations with Germany; there may be an appetite in the Kremlin to reverse that.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

COVID-19 and the fall of energy prices have put serious financial burdens on Russia. The cost of the Donbas occupation might be something that the Kremlin, after seven years, may be interested in shedding. Given the devastated state of occupied Donbas, the Kremlin may see an advantage in its return to Kyiv’s control, thus making it Ukraine’s problem to fix.

Sanctions alone will not compel Russia to withdraw from eastern Ukraine. But relief of sanctions related to NS2 and the Donbas as part of a broader package leading to more normal economic relations with the West may serve the Kremlin’s purposes.

The Kremlin may also see the inclusion of a few million voters from the currently occupied Donbas into the Ukrainian political system as an important plus. These voters could be expected to be more mindful than other Ukrainians of the need to take Russian interests into account.

Of course, the Kremlin would have to explain a policy shift on Ukraine to the Russian public. The Kremlin needs to avoid the optic of being seen as abandoning Russian-speaking “compatriots.” But opinion polls indicate that average Russians have become wary of foreign adventures. The Kremlin’s PR machine is up to the task of spinning a deal as a victory for Russia, if so ordered.

NS2 at its core was always about diverting gas flows from Ukraine and cementing Russian-German energy and economic ties, not about major new Russian gas supplies for Europe. Following Russia’s cutoff of gas flows through Ukraine in 2009, the EU and individual members like Poland took steps to address the threat of Russian efforts to dominate the European gas market. Poland, for example, has built significant LNG import facilities on its Baltic coast and is completing a gas pipeline with Norway. As a result, Poland is no longer at the mercy of Russia for its natural gas.

Ditte Juul-Jorgensen, Director General for Energy for the European Commission, stated flatly in February that the EU does not need the NS2 project to ensure security of natural gas supply. Rather, she noted that investments made over the past decade on LNG terminals, interconnectors, and storage had secured adequate gas supplies to meet EU needs without NS2. The accelerating push in the EU to transition to renewables under the Green Deal has also served to make the NS2 project even more of a redundancy.

The US was right to oppose NS2. But timing is everything. If the Trump administration had been serious about stopping NS2, it should have done so in summer 2017 when the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions (CAATSA) legislation became law and NS2 construction had still not begun.

But the US missed the boat. Secretary Tillerson gave a pass to the NS2 project and that pass, in the form of State Department “guidance”, remained in effect for years after he left. European energy companies, which at Gazprom’s behest had put up five billion dollars to finance half of NS2 construction, were thus deprived of clear grounds upon which to exit.

Enter Congress, belatedly, which passed mandatory sanctions in December 2019 targeting pipe-laying vessels involved in NS2. The Swiss pipe-laying company Allseas immediately pulled out, halting the project. But by this time, NS2 was largely completed.

Eurasia Center events

Meanwhile, the impasse in occupied east Ukraine has centered around the Kremlin’s insistence on a federalized “special status” for the region. This would undermine Ukrainian statehood. For any deal to happen, the Kremlin will have to accept the decentralized status now in place in all regions of Ukraine as sufficient. That would be a major concession. Unless something more is put on the table, such as a green light for NS2 and better trade and economic prospects for Russia, there is no prospect the Kremlin will accept such terms.

Furthermore, the occupied territory should be turned over to OSCE interim administration. Following a reasonable interval, elections supervised by the OSCE should be held in the territory under Ukrainian law. Ukraine would then assume full control. Once that happens, the US would end sanctions on NS2 and the US and EU would end sanctions related to Russia’s aggression in eastern Ukraine.

Germany’s decision to move forward with NS2 even after Russian aggression in Crimea and the Donbas was a cynical move. It is therefore incumbent on Germany to help fix the mess they helped create. The Navalny poisoning should be a motivator. There is a precedent: German diplomacy played a constructive role in late 2019 in helping Ukraine obtain guaranteed volumes for transit of Russian gas for the subsequent five years. Germany should reaffirm its commitment to ensure that significant volumes of gas would continue to transit Ukraine after NS2 is online.

Getting Donbas back on its terms would be a big win for Ukraine. Naftogaz would suffer from a drop in gas transit revenue when NS2 comes online, but it is already adjusting for that. Indeed, the natural gas relationship with Russia has been such a source of corruption in Ukraine since independence that a lessening of these ties is far from all bad. Germany and the EU should also pledge to explore using the Ukrainian gas transit system as a future conduit for hydrogen gas, as that source is developed. That would soften the financial blow.

If all countries were led by angels, there would be no need for diplomacy. Demanding that the Kremlin do what is right, but without making it worth their while, will lead nowhere except to a perpetuation of conflict. The current spike in tension in eastern Ukraine makes the danger clear and threatens to torpedo potential progress in other vital areas in US-Russian relations, such as arms control. It is time for a new paradigm.

A potential NS2-for-Donbas deal would be in the interest of all parties. And if the Kremlin were to reject it, then the path of more sticks and fewer carrots remains open.

Colin Cleary is a retired Senior US Foreign Service Officer. He was Director for Energy Diplomacy for Europe in the Energy Bureau at the State Department. He also served as Political Counselor at US Embassy Kyiv and Science Counselor at US Embassy Moscow.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

Image: Pipes for the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline in storage at the port of Mukran. (Stefan Sauer/dpa via REUTERS)