On April 6, 2018, the Trump Administration imposed stiff economic sanctions on 37 Russian oligarchs, oligarch-owned companies, Russian government officials, and state-owned companies.

Our fellow Brian O’Toole called it “far and away the most significant sanctions action against Russia since the imposition of sectoral sanctions in 2014.” This edition of our EconoGraphic series uses the example of the sanctioned Russian aluminium producer United Company RUSAL, which is controlled by the sanctioned Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, to illustrate how the potent combination of primary and secondary sanctions can impact global supply chains and markets.

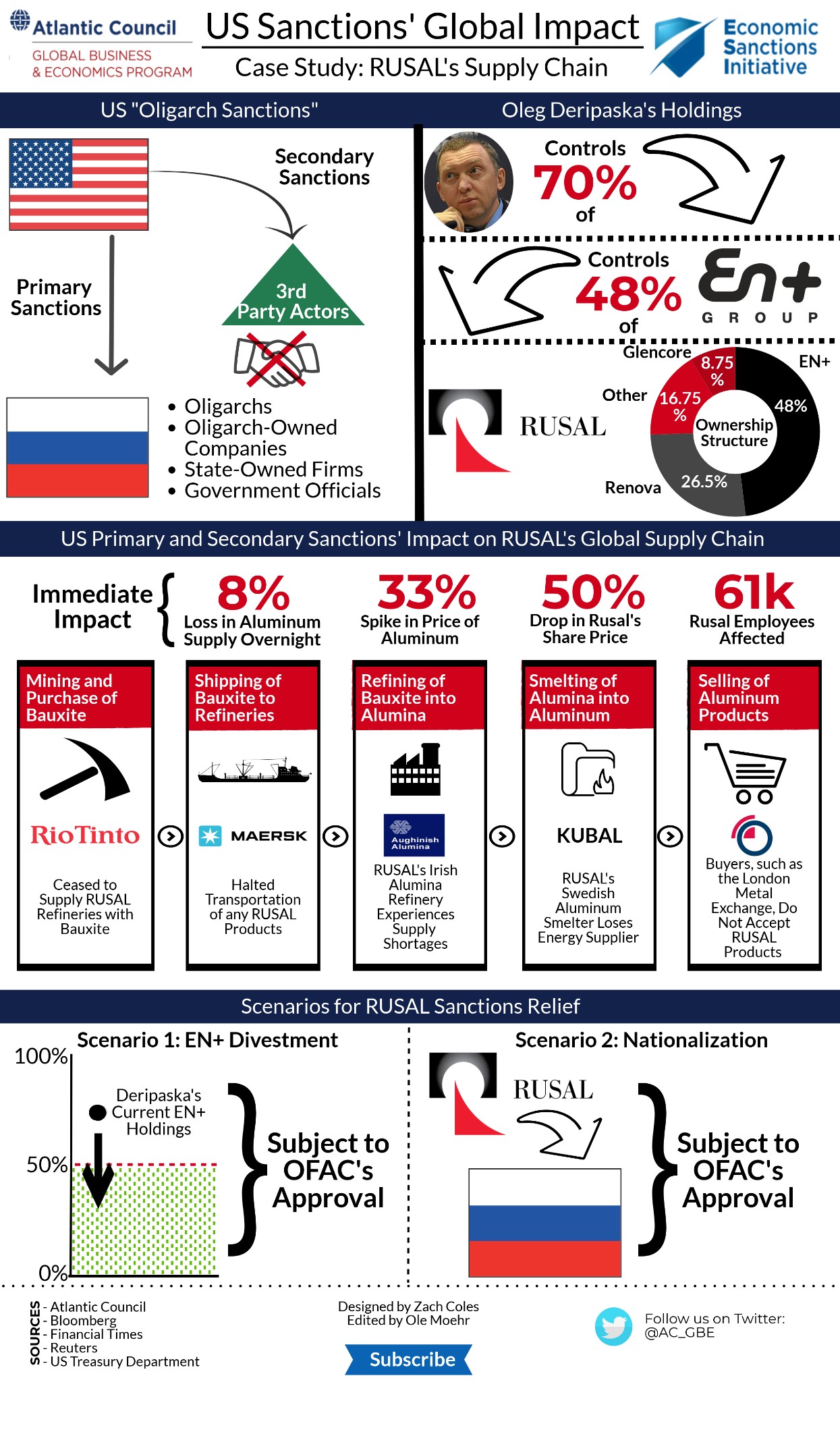

First, a brief review of how the primary and secondary sanctions work in practice. The primary sanctions, which the US Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) announced on April 6, freeze any assets under US jurisdiction that are owned or controlled by the 37 Russian individuals and entities. In addition, US persons (i.e. individuals and corporations) are not allowed to engage in any dealings or transactions with the sanctioned Russian oligarchs, officials, and companies. For RUSAL, whose operations are tightly interwoven with global commodity supply chains, this means that it is prohibited from making or accepting payments in US dollars. This in turn effectively cuts RUSAL off from global commodity markets. RUSAL is subject to sanctions because Oleg Deripaska controls the company through a combination of his EN+ Group’s minority stake in RUSAL with a shareholder agreement that includes fellow sanctioned oligarch Vikor Vekselberg’s Renova Group and the multinational trading company Glencore. To amplify the impact of these primary sanctions, OFAC also imposed Congressionally-mandated secondary sanctions on April 6 that are meant to deter non-US persons from engaging in any “significant transactions” with the 37 Russian individuals and entities. In practice, any company or individual that does significant business with RUSAL and/or is involved in the company’s supply chain could become a sanctions target.

By sanctioning RUSAL, the world’s second largest aluminium producer, the US administration shocked commodity exchanges, caused a jump in aluminium prices, and threatened to disrupt manufacturing processes of aluminium products around the world. RUSAL’s large global footprint, operating in 12 countries, and deep integration in the global aluminium supply chain exposes its business operations to US sanctions. Following the imposition of sanctions, the multinational mining company Rio Tinto declared a force majeure (i.e. an event or effect that cannot be reasonably anticipated or controlled) to justify its decision to stop supplying bauxite to RUSAL’s alumina refineries. To produce primary aluminium, Bauxite is mined and refined into alumina, which is then processed into aluminium. Rio Tinto is not only an important supplier of bauxite, but also a big buyer of alumina from RUSAL’s refineries. This illustrates how the sanctions affect both inputs and outputs in RUSAL’s supply chain. As a result, RUSAL’s alumina production might be severely disrupted. RUSAL refines 64 percent of its alumina outside Russia. Alumina refineries, including RUSAL’s Irish plant, might be forced to shut down. Similarly, RUSAL depends on shipping and logistics companies to connect its own operations as well as its web of suppliers and customers. After the US announced the sanctions, the shipping companies Maersk and Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) suspended the transport of any RUSAL-related products. If RUSAL is unable to replace key upstream companies, such as Rio Tinto and Maersk, its global supply chain would effectively be broken. This would jeopardize the existence of RUSAL in its current form. Further downstream, the Kubal aluminium smelter in northern Sweden, RUSAL’s only smelter in Europe, lost its primary energy supplier because of the US sanctions and faces the prospect of ballooning electricity costs. The smelter also stopped receiving deliveries of alumina. Finally, end users, such as can makers, car manufacturers, and the airplane industry, began buying aluminium from different sources. Commodity exchanges, including the London Metal Exchange, reacted to the sanctions by prohibiting deliveries of RUSAL products to its warehouses. As explained above, any non-US company that engages in a commercial transaction with RUSAL is at risk of becoming a target of US secondary sanctions.

Following global market’s strong reaction given RUSAL’s vital role in global aluminium production, and growing pressure from US companies as well as key European countries, including France and Germany, the US government offered RUSAL a path toward sanctions relief. On April 23, OFAC extended the deadline for investors to sell their interests in RUSAL from May 7 until June 6. In addition, US and international companies will now have until October 23, instead of June 5, to wind-down their business transactions with RUSAL. US Treasury Secretary Mnuchin further reassured markets by stressing that the sanctions are aimed at Oleg Deripaska and not RUSAL. He indicated that primary and secondary sanctions against RUSAL could be lifted if Deripaska divests his controlling stake in the company. These actions triggered a drop in the price of aluminium and potentially allowed key components of RUSAL’s supply chain, such as the Irish alumina refinery and the Swedish smelter, to continue to operate for the next few months. The long-term outlook is less certain. Should the sanctions not be lifted after the wind-down period ends, RUSAL-owned companies outside of Russia might have to change ownership to avoid going under.

There are two often cited scenarios for the future of RUSAL. First, Mr. Deripaska could reduce his stake in EN+ from currently 70 percent to less than 50 percent to relinquish control of RUSAL and open the door for the sanctions to be lifted. Of course, Deripaska would also have to cancel the above-mentioned shareholder agreement with Vekselberg’s Renova Group and Glencore that allows him to control RUSAL. In principle, Deripaska has agreed to do both. However, since RUSAL is listed on OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN), a divestment by Deripaska will not automatically lift the sanctions against RUSAL. Instead, the Treasury Department will have to manually remove RUSAL from the SDN to revoke the sanctions. Thus, even if Deripaska reduces his stake in EN+ below 50 percent, OFAC might decide to keep the sanctions against RUSAL in place because the new ownership structure does not meet the US government’s requirements. In the second scenario, the Russian government would buy Deripaska’s share to nationalize RUSAL and shield it from the US sanctions. Yet, such a step would likely not satisfy the US government’s conditions for lifting sanctions against RUSAL. In turn, RUSAL’s assets, especially those outside of Russia, would continue to suffer from the sanctions. OFAC in the past has pursued divestiture that does not confer significant benefit to the target of the sanctions, which suggests that Deripaska may not have an easy or lucrative way out. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Russian government is reportedly exploring ways to provide financial support to RUSAL in lieu of nationalizing the company.

For a more in-depth look at the impact of secondary sanctions, read our issue brief “Secondary Economic Sanctions: Effective Policy or Risky Business” by Atlantic Council senior fellow John Forrer.