When it comes to women and the Islamic Republic, “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.”

For forty years, women have resisted the Islamic Republic’s attempt to deny them rights previously won. They have waged a war—on the streets, in social media and even in the privacy of their homes—for equality and against the regime’s attempts to impose on them a broad range of controls.

When I say “women,” I mean all women—liberal and conservative, religious and secular, old and young. Women were already growing conscious of their rights and sought to expand their participation in society under the monarchy; this trend continued after the 1979 revolution. Even today, women remain the most vocal group pushing back against a regime bent on societal control.

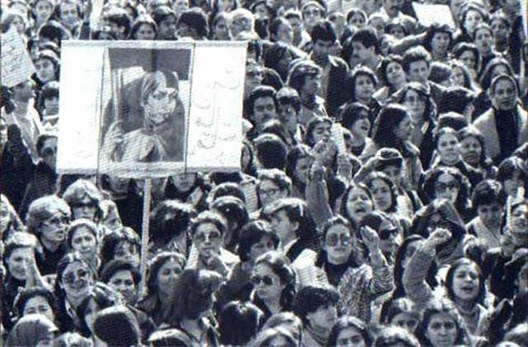

On March 8, 1979, on the occasion of International Women’s Day and one month after the establishment of the Islamic Republic, women poured into the streets of Tehran to protest the imposition of the veil. They marched to the prime minister’s office, where then Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan was shocked to hear that thousands of women stood outside his gates. The protesters were attacked by thugs and hooligans and had to take refuge in side streets. For women, this was a taste of what was to come. They had supported the revolution; tens of thousands had joined the marches against the monarchy. Little did they know that, once in power, the revolutionaries had no interest in promoting women’s rights, nor did they want women demonstrators in the streets.

One of the first acts of the new regime was a decree issued by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the revolution, to suspend the Family Protection Law. This law, enacted in 1967 and revised in 1975, was one of the most progressive of its kind in the region. It gave women the right to seek a divorce, raised the age of marriage to eighteen for girls, and allowed a man to take a second wife only with the consent of his first wife and the permission of a family court. In effect, polygamy became very difficult and temporary marriage—a permitted practice in Shia Islam—was discouraged. Child custody would go to the mother unless the courts decided otherwise. Wives received the right to prevent their spouses from pursuing a profession, for example, drug dealing or smuggling, that exposed the family to danger or dishonor. This was a right that, until the passage of the law, was granted to husbands only.

With a stroke of a pen this progressive family law was suspended. Overnight the age of marriage for girls was reduced from eighteen to nine; it took ten years of effort by women activists to raise it again, but only to thirteen. Women lost the right to seek a divorce and the right to child custody. Family protection courts were dissolved, eventually replaced by civil courts, and women no longer could become judges. Polygamy once again was permissible under the law.

At the same time, women were gradually eased out of government offices and were barred from specified fields of studies such as agriculture and law. Male instructors were barred from teaching in girls’ schools. At the university, women and men ended up sitting in separate sections of the classroom.

The new regime interfered with the daily lives of women. Unless related as brother and sister, father and daughter or husband and wife, men and women could not walk together on city streets, be together in a car, attend movies or shop together. The ubiquitous Revolutionary Committees could arrest anyone who violated these rules. The sanctity of the home and of privacy was erased. The Revolutionary Committees felt free to barge into peoples’ homes if they suspected mixed gatherings and alcohol consumption were taking place. The streets became a sea of black, brown, and navy manteaus (ankle-long coats) and head covers; bright colors were banned. Smiling was frowned upon. Only loose women, it was assumed, would smile at strangers or laugh out loud in public.

The Islamic punishments of lashing for violating the Islamic dress code, stoning for adultery and the amputation of hands for theft became the law of the land. The regime showed no respect for human rights, let alone women’s rights.

Despite all these pressures, Iranian women, after the initial shock and having reluctantly adjusted themselves to the new environment, began to push back—first in small, incremental steps to test the waters and then by leaps and bounds. Women succeeded in reversing the laws barring them from fields of study in higher education. Today women comprise between fifty and sixty percent of entering classes at universities. Some minor adjustments were made to the Family Law. For example, as noted, the age of marriage was raised to thirteen for girls; and while no woman can preside as a judge, women lawyers regularly appear in courts to represent clients. Most fields of employment are open to women; among the younger generation, families of two wage earners are common.

Politically, women have fared better. Women were never denied the vote and they have been voting in large numbers in parliamentary, presidential and local council elections. A substantial number of women seek political office, including for parliament and president—although a woman has yet to be allowed to run for the later position. Today, seventeen women sit in parliament. In the current government, there are two women vice-presidents, one woman ambassador, four women governors of minor provinces and a handful of women mayors. In the last forty years, only one woman was appointed to the cabinet as minister. Even reform presidents—Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Mohammad Khatami and Hassan Rouhani—were unable to appoint a woman as a minister because of hardline clerical opposition.

Four decades after the revolution, the old tactics of repression, intimidation, imprisonment and even torture continue, but they haven’t intimidated or silenced women—and they can’t. Just a year ago, a young woman sparked a mini-movement by standing in a prominent spot on a Tehran street and publicly, defiantly, removing her headscarf. The practice quickly spread; other women selected a visible spot on a city street and removed their scarves. They were arrested and sentenced to long prison terms, but that did not stop them.

The fact is that, today, the regime is dealing with a new generation of women, the children of the revolution. In 2006, they launched the One Million Signatures for the Repeal of Discriminatory Laws movement. The movement aimed at collecting one million signatures on a petition for equality under the law. The initiators of the movement were arrested and sentenced to prison terms. Again in 2009, young people including many women poured out into the streets in massive numbers shouting, “Where is my vote?” believing that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected to a second term as president in an engineered vote count. Many of them also suffered arrest, torture and prison terms.

This generation of Iranian women is as bold as its predecessor and, in fact, bolder—unafraid to speak out and determined to secure the legal, social and personal rights they believe are their due. They continue to push the boundaries. They continue the struggle against the regime in social media and on the streets in big cities, small towns, and villages. They represent a backlash against a bullying government and difficult economic conditions. They are not easy to control.

Meanwhile, on the streets of Tehran, all is no longer drab and dark. The long manteau hardly exists; coats have become increasingly shorter and brighter. The streets are full of color—a sea of color like a fine Persian carpet. This generation of young women—and men—may yet prove to be the instrument of fundamental change in the country.

Haleh Esfandiari, the former and founding Director of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, is a Public Policy Fellow at the Wilson Center.

Image: Iranian women protest the imposition of the veil on March 8, 1979 (fozoolemahaleh)