Someone once asked if Cairo graffiti was a trend that would die out eventually. As a documenter of the past 18 months’ worth of street art around Cairo, I had noticed that most street art was sparked, influenced and shaped by politics. Graffiti was made for, during and after protests on the streets of Cairo, announcing, educating and commemorating.

Aside from the sporadic stencil and experimentation with freehand styles here and there, the Cairo street art scene had experienced a lull in recent months, equally reflected in the political scene: save for the recent US embassy protests, in which a very small but vocal representation of the Cairo population participated, very little had happened to spark a renewed surge in a quantifiable protest movement and protest art.

Then, three nights ago at around three in the morning, Egyptian government workers began to paint over graffiti on the Mohamed Mahmoud wall, just off of Tahrir Square. As they whitewashed the wall, a row of central security foot soldiers guarded them against a cluster of angry citizens and bystanders, decrying them for their inhumane act. Why was it inhumane? The Mohamed Mahmoud wall carried a magnificent mural that depicted just some of the 75 young football fans who were crushed and stabbed to death in a riot at Port Said stadium on February 1st, 2012. A group of graffiti artists led by Ammar Abo Bakr started working on the mural one day later as a tribute and memorial of the young martyrs– it was a labor of love and dedication that took over 50 days and thousands of pounds’ worth of paint and equipment to complete.

Portraits of the Ultras who were killed in Port Said in February, 2012

Much has been written about the mural, visitors have flocked from all around Cairo and the world to photograph the mural and interview the artists, and the American University in Cairo (AUC), whose wall carries most of the massive mural, succumbed to pressure from the street and its own faculty to preserve the mural and prevent government workers from removing it.

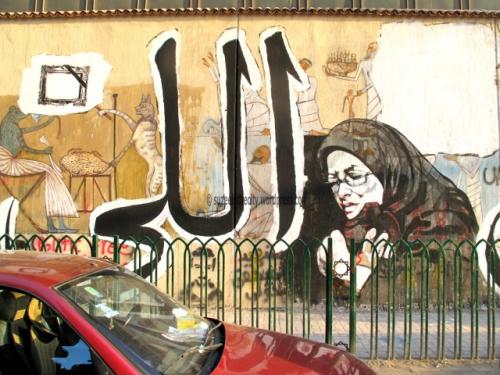

Several months after the mural was completed, it became a shrine for the families of the dead youth and an open museum where bystanders would read the names of the martyrs remember their faces and pose for photographs in front of their favorite images. Abo Bakr and his friends returned to the mural and added a new and shocking layer: the faces of martyrs’ mothers dressed in funeral black and hugging photographs of their sons, and the phrase ‘Forget what has passed and stick to the elections instead.’

Forget what has passed

And stick to the elections instead

The act of painting over a mural that gained so much emotional power and became an integral part of the visual memory of the revolution was shocking in itself; the sarcastic message that the artists had added was even bolder: Abo Bakr said that the Egyptian conscience had become too preoccupied with the presidential elections of May 2012, and had forgotten about the serious issue of justice: the Port Said trial had extended over several months until public interest had faded and eventually all perpetrators and officials accused of involved were exonerated of all charges. This was the last straw; and the last of several trials over the past year in which policemen accused of killing protesters during the January 25 uprising and beyond and officials accused of issuing the orders were found innocent of all charges.

The mural managed to move from an emotionally evocative memorial to a shocking reminder of everything we lost in the fires and what little we had gained. And then, when the mural was painted over on September 18, 2012, we had lost that little gain. Street art is one of the few tangible testaments to one of the revolution’s greatest triumphs: breaking the fear barrier, which enabled hundreds of young Egyptians to reclaim their public space and produce their personal expressions through graffiti. Erasing the Mohamed Mahmoud mural – arguably the largest and most famous example of street art in Cairo – was a senseless and clumsy attempt to regain control of the public space, of enforcing authoritarian order and also – most importantly – erasing a visual historical archive that doesn’t glorify or glamorize the authorities.

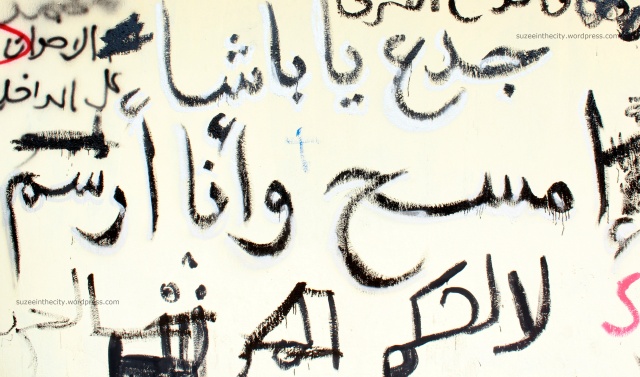

It was also poorly timed; the public conscience has not forgotten the martyrs of Port Said yet, and the importance of Mohamed Mahmoud’s walls and all the bloodshed and violence it witnessed had not diminished. Barely after the white paint had dried, street artists, political activists and relatives of the martyrs attacked the walls with fierce scribbles full of lewd attacks on the government, the police and Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi.

Keep [wiping it off], you cowardly regime

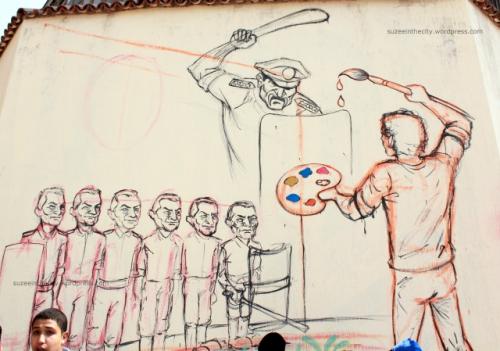

The face of Hosni Mubarak returned to haunt the walls, appearing on the heads of a row of soldiers protecting a baton-wielding officer from a paintbrush-holding artist. The message is clear. The new regime was no different from the old; one had killed protesters, and the other had betrayed them. Of all the taunts, insults and warnings, the largest two were ‘Vindication’ and ‘Keep wiping it off and I’ll repaint’, a testament that street art carries on the spirit of the January 25 revolution: unabated resilience to fight for justice.

The following night, supporters of the Freedom and Justice Party – the Muslim Brotherhood’s political arm – painted the party’s logo on the wall and wrote ‘the revolution is an idea, not a memory’, as if to justify the removal of the martyrs’ mural. Barely hours later on Friday morning, the slogan had been removed and new graffiti appeared: the familiar faces of Sheikh Effat, Mina Daniel and 14-year-old Anas returned – all martyrs who had previously been commemorated by the artists on the Mohamed Mahmoud walls.

Mohamed Morsi’s face was painted onto a queen of clubs, as nearby Banksy’s rats were replicated, one holding a paintbrush while the other stood by. At the very end, a masked warrior straddled a horse against the Egyptian flag, carrying a paintbrush beneath the message ‘graffiti will never end’. This is just one of many layers of graffiti that will be made over the coming days.

Before: A martyr’s mother hugging a photo of her son, who died in the Port Said riots in February 2012

Now: Graffiti of Morsi and Mubarak, one and the same

The Egyptian presidency and Interior Ministry have denied issuing orders to remove the graffiti, a claim that is hard to believe considering that admission would mean neither party has control over its streets. In an attempt to placate the angry artists, Prime Minister Hisham Qandil allegedly offered to allocate youth cultural centers where graffiti could be made, completely missing the point of it all.

If the goal was to clean the walls, the new graffiti is far more sordid and chaotic than the previous mural. By preserving and protecting the Mohamed Mahmoud mural, AUC had managed to establish a sense of calm and order. Now, the mess is an explosion of colours, words and clear outrage. The artists are now back in droves on the walls, painting, designing and discussing ambitious collaboration projects. If the goal was to suppress or crush the Cairo graffiti scene, then the erasing of the wall did the exact opposite.

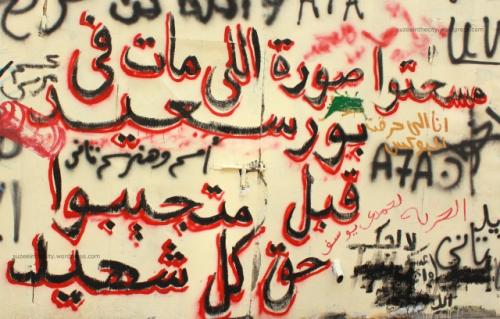

You wiped off the faces of the martyrs of Port Said before you vindicated their deaths

Soraya Morayef is a journalist and writer based in Cairo. She blogs under suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com

Featured image reads: Keep wiping it off and I’ll repaint

All images © Soraya Morayef

Image: Wipe%20it%20off.jpg