August 26, 2021

Before the Taliban took Afghanistan, it took the internet

The Taliban insurgents who conquered nearly all of Afghanistan in just two weeks counted social media among their weapons. They deployed Facebook and WhatsApp to help prevail over their opponents on the battlefield. They issued hundreds of premature declarations of victory via Twitter—using spam to amplify their messages and create a sense of inevitability. Their smartphones proved just as handy as their rifles when they entered Kabul on August 15, enabling them to film the first propaganda footage of their occupation.

Many Western observers have expressed surprise at the sophistication of these Taliban information operations. Some have suggested that this new media savvy signals the birth of a fundamentally different movement: a “Taliban 2.0.”

Yet this is an oversimplification. A closer review of the group’s history and the conflict in Afghanistan reveals that the Taliban has waged—and now won—a singular, focused, twenty-year information war. While the platforms and methods of this conflict have evolved, the Taliban’s Islamic fundamentalist goals have not.

This article examines the evolution of the Taliban’s information operations, focusing especially on the group’s aggressive exploitation of the internet. It charts three periods: the origins of the Taliban’s propaganda and early digital strategy (2002-2009), its adoption of modern social media platforms and distribution techniques (2009-2017), and its rapid ascent and diplomatic legitimization (2017-2021), which vastly expanded its access to online tools and services.

For a generation, the Taliban clearly articulated the purpose of its propaganda regime. This information strategy helped the Taliban seize power in Afghanistan. It will likely continue to guide Taliban actions in the months ahead.

Going digital (2002-2009)

The Taliban rose to prominence in 1993 amid the decade-long civil war that followed the Soviet Union’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. Many of these militants hailed from Afghan refugee camps in western Pakistan, where they had been educated in schools devoted to a deeply fundamentalist sect of Islam (talib means “student” in Arabic).

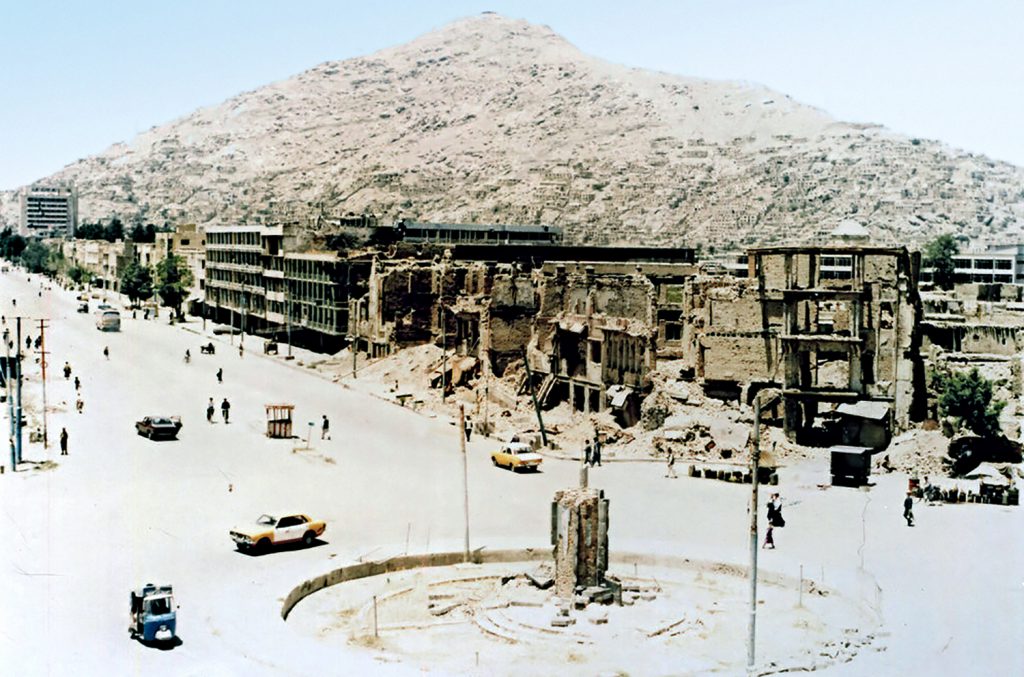

By 1996, the Taliban had consolidated control over enough of the country to declare the creation of the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.” Although strict Sharia law had never been especially popular in Afghanistan, it came to govern every aspect of daily life under the group’s rule. Women and girls were treated as property. Religious minorities were persecuted. Those who didn’t belong to the ethnic Pashtun majority were targeted for mass killing.

Despite the Taliban’s Islamic fundamentalism, it had little in common—at first—with the anti-Western, pan-Islamic jihadism preached by groups such as al-Qaeda. The Taliban did not want to remake the world; it wanted to rule Afghanistan. Indeed, it tried for several years to win representation in the United Nations. Even as it banned photography, television, and the internet at home, the Taliban sought to be portrayed positively in Western media, going so far as to launch its first primitive website (www.taliban.com) in 1998. Yet the group could not obscure evidence of its obvious atrocities. The Taliban’s decision to give refuge to the virulently anti-Western Osama bin Laden in 1996, and to support his anti-US fatwa two years later, was an acknowledgement that its engagement strategy had failed.

After the 9/11 attacks and the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the Taliban was temporarily shattered. Rebuilding its forces in the relative safety of Pakistan’s western tribal regions, it prepared for a decades-long insurgency. The group’s success would largely be decided by its ability to shape the information environment and rapidly disseminate narratives promoting its own benevolence and casting the United States and US-backed Afghan forces in a negative light.

In 2002, the Taliban founded a revitalized media arm that focused on winning legitimacy, both among the local populace and in the eyes of the international community, and undermining the US-backed Afghan government. That same year, the Taliban also suspended its ban on “living images.” The propaganda value of photographs and videos of dead Afghan civilians, allegedly killed at the hands of the US occupation, was too great to ignore.

Initially, the group did not invest heavily in a formal web presence. Instead, it focused on propaganda materials that could be spread in the predominantly rural areas where Taliban fighters operated. These often took the form of shabnamah (“night letters”), delivered surreptitiously under the cover of darkness, which exaggerated the Taliban’s power and threatened violent retaliation against anyone who aided US forces or the Afghan government. The Taliban also distributed audio cassettes—well-suited for a population in which adult literacy was still a relative rarity.

Even in these early stages, the Taliban demonstrated an interest in studying and emulating the propaganda of other terrorist and insurgent groups. When al-Qaeda in Iraq made international headlines by beheading hostages and circulating the footage on DVDs, the Taliban tried the same thing. But as public backlash grew, the Taliban determined that the beheadings were alienating the Afghan people. It reverted to shooting its prisoners instead.

The official website of the Taliban insurgency, Al Emarah (The Emirate), came online in 2005. It published in five languages: English, Arabic, Pashto, Dari, and Urdu. Much of its content came in the form of short, rapid-fire press releases either claiming various victories over the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) or disputing casualty figures. Later, this constellation of websites would grow to include downloadable audio and video propaganda. Curiously—and perhaps because of its single-minded focus on capturing Afghan territory—the Taliban did not seek to cultivate the same web-forum and chatroom culture that characterized global Islamic terror movements of the period.

Yet even as it sought to influence and manipulate it, the group exhibited deep anger toward media. In a 2006 Pashto-language statement, the Taliban complained about widespread bias in news reports, threatening violence if the situation did not improve. “Many news sources cruelly treat the Taliban,” the statement read. “They do not air our reports… We will kill anyone who mistreats us like this.” At the same time, the group was becoming adept at quickly spreading its preferred narratives. In a 2008 interview, the Taliban’s then-information minister bragged that it took twenty-four hours for the Afghan government to put out a press release to journalists, “while we can give the information through satellite phones in record time.”

The group’s information operations, however, were far from seamless. The “Taliban” label had long been claimed by a shifting coalition of other Islamic militant groups, led by warlords with different backgrounds and aspirations. This organizational confusion extended to the Taliban’s propaganda apparatus: For years, Taliban officials alternated between fury and frustration as they dealt with a flood of fake or unauthorized spokespeople.

By 2008, however, Taliban communications had been consolidated under the control of a few individuals. One of these men (or a group of men, according to media speculation), referred to publicly as “Zabihullah Mujahid,” would become the online voice of the Taliban for the next thirteen years. In August 2021, a man claiming to be Mujahid gave the Taliban’s first press conference in the conquered city of Kabul.

He sat in the chair of the former Afghan information minister assassinated by the Taliban only several weeks earlier.

Harnessing social media (2009-2017)

In 2009, the Taliban posted an English-language message on its website regarding the stakes and objectives of its information war. In short, it accused the West of a concerted disinformation campaign:

“[T]he biased media constantly publish the official story and the people under the influence of the partial reports are confused and some time [sic], misjudge the events because they do not know to tell facts from lies. On the other hand, the mainstream media do not publish the stand of Mujahideen regarding every event, fearing the invading Americans will accuse them of helping the so-called terrorists. In fact, the world has now been taken hostage by the media suffocation unleashed by the colonialism.

“Pentagon [sic] has a psychological war department. This department is charged with spreading lies against Mujahideen. They spend millions of dollars to try to make it possible that the lies fabricated in the Pentagon reach every ear in the world.”

The Taliban also offered a solution: “Those journalists who are committed to human dignity, liberation, and justice should form Mujahideen Support Groups,” the message continued. “[They must] wage an unwavering and constant campaign against the black propaganda launched by the colonialists.”

It was no longer enough to simply bombard Western journalists with press releases—the militants needed an online network of advocates and supporters. The answer lay in social media.

Seeking to expand the reach of its propaganda videos, the Taliban joined YouTube in 2009. It also added a Facebook “share” button to its website. By 2011, the Taliban was posting regular updates to Facebook and Twitter. Whereas it had once been largely insular, the group was now cultivating a network of friendly bloggers. In turn, these digital voices worked to associate the Taliban more directly with pan-Islamic and pan-Arab causes, seeking to tie its mission to popular movements such as the Arab Spring.

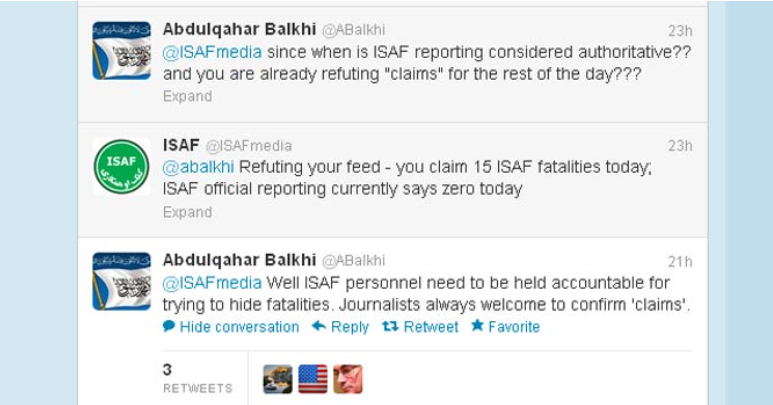

As the Taliban’s propaganda apparatus expanded, it was also enjoying a reversal of fortune on the ground. The insurgents had re-established effective shadow governments in several Afghan provinces and become more militarily aggressive, often engaging US and NATO soldiers directly. The group’s Twitter presence seemed especially designed to capitalize on this, sharing details about various battles—even providing comments to Western journalists—hours before ISAF or the Afghan government could muster a formal announcement. A survey of the Taliban’s 2012 Twitter activity found surprisingly little evidence that it was inflating the number of ISAF or Afghan troops that it killed. But the Taliban never acknowledged the thousands of civilian deaths that it caused.

When the horror of the Syrian civil war gave rise to the Islamic State beginning in 2013, the Taliban watched carefully. Although it had no love for the group—the Taliban would ultimately battle the ISIS franchise in Afghanistan—it appreciated the Islamic State’s highly effective viral propaganda. It also appreciated how US coalition forces had exploited ISIS fighters’ incessant social media use to trace and kill them. In 2015, the Taliban announced the launch of Telegram and WhatsApp channels. Not only did this move improve the group’s outreach efforts, but it also pulled communications onto encrypted platforms—and beyond the reach of US military intelligence.

As time passed, Taliban propaganda increasingly resembled the content flowing out of ISIS-controlled Syria and Iraq. Video quality notably increased, and there was a new emphasis on action—typically firefights or suicide attacks—set to Islamic nasheeds (chants) and sometimes filmed by drones.

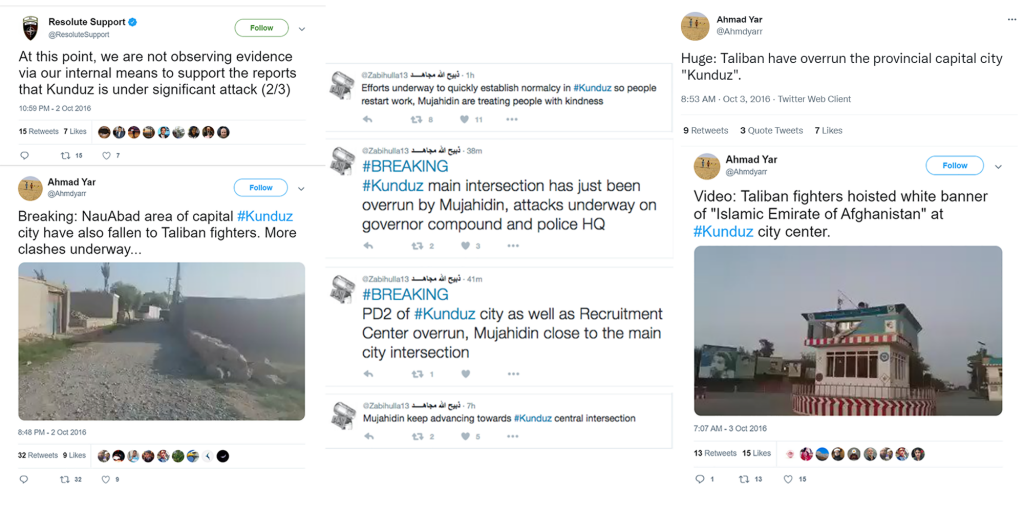

During a series of assaults on the city of Kunduz throughout 2015 and 2016, a surprising number of Taliban fighters carried smartphones. In one case, militants shared triumphant selfies as Afghan civilians tweeted for help just a few blocks away. In another, they captured a major downtown intersection and hoisted the Taliban’s white flag, holding the spot for several hours. As Taliban propagandists and Kunduz residents flooded Twitter with video evidence, the ISAF spokesperson’s account was still insisting that a major attack had not taken place.

For years, the Taliban’s digital operations flourished amid relative inaction by social media companies. Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter only sporadically deleted Taliban content when it got too graphic or attracted the anger of US policymakers. But after 2014, as those platforms acceded to public pressure to stop hosting Islamic State propaganda, the Taliban was swept up in the resulting crackdown.

When the Taliban launched a Pashto-language Android app in late 2016, for instance, the app was almost immediately yanked from the Google Play store. Although the Taliban never disappeared from these services, it became harder for the group to maintain persistent accounts and distribution networks. Instead of spamming Facebook with loud propaganda, Taliban militants were more likely to use the service to locate possible targets for reprisal, in part by identifying and tracking them through their public profiles.

After years of embarrassment at the hands of the Taliban’s increasingly adroit internet presence, the Afghan government was also determined to destroy this propaganda apparatus. As ISAF combat missions ended and many US troops left the country, Kabul inherited more power over matters of public transparency, public relations, and information policy. But it would not use this power well.

Winning the information war (2017-present)

By 2017, the US-backed Afghan government was becoming less forthcoming about combat operations and more willing to engage in censorship. For years, the US military had periodically disclosed figures related to the strength, performance, and attrition of Afghan forces, as well as estimated US and Afghan military and civilian casualties. By late 2017, at the request of the Afghan government, these figures were withheld from the Afghan and US public.

At the same time, Kabul ordered a twenty-day shutdown of WhatsApp and Telegram inside the country, citing unspecified “security reasons.” Afghan journalists erupted with fury, arguing that the ban was incompatible with the constitutional guarantee of free speech. Facing mounting public outrage, the Afghan government reversed course. But the damage to its credibility had been done.

Naturally, the Taliban reveled in claiming that it was more accessible and transparent than Afghan government spokespeople. Indeed, it did all it could to handicap officials even further. As part of their battle preparations, Taliban fighters began sabotaging nearby cellphone towers, limiting the Afghan government’s ability to communicate with local citizens and issue timely updates. As Zabihullah Mujahid explained to The New York Times in a 2016 interview, the purpose was to create an information vacuum—one that the Taliban could fill itself.

In 2018, then-President Ashraf Ghani announced a three-day, unconditional ceasefire with the Taliban, leading to the first (brief) truce in the country since 2001. Crucially, news of the ceasefire came first via Ghani’s Facebook page, an indication of how drastically Afghanistan’s information environment had changed. At the time of the US invasion, the internet and cellphones were virtually nonexistent. By 2018, roughly 40 percent of Afghan households had access to the internet—and 90 percent to a mobile device. Social media, no longer merely a novelty or plaything of the rich, had become a pillar of Afghan civic life.

By 2019, the Taliban’s digital propaganda had fully matured. It issued rapid-fire English-language news alerts about ongoing battles, often accompanied by ready-to-share infographics and short video clips. Zabihullah Mujahid’s Twitter account—which had enjoyed a stable presence on the platform since 2017, with the first hint of informal Afghan-Taliban peace talks—was now regularly amplified by a network of spam accounts intended to boost his reach.

According to a 2020 study of Twitter use during the conflict, Mujahid’s account tweeted more frequently—that is, more than fifteen times daily—than the rival Afghan Ministry of Defense account. It also enjoyed roughly twice as many followers.

The Taliban also appeared to moderate its tone, at least when addressing the international community. In an English-language press release following the 2019 anti-Muslim terror attack in Christchurch, New Zealand, the Taliban called for investigation—not jihad. “We ask the government of New Zealand to prevent the repeat of such occurrences [and to] carry out a comprehensive investigation to find root of cause [sic] of such terrorism,” the Taliban said. Its words contrasted sharply with statements from al-Qaeda and ISIS leaders, who called for bloody vengeance against the West.

In 2019, the United States entered formal peace talks with the Taliban. A year later, US and Taliban representatives reached a formal settlement, agreeing to the withdrawal of all US and international forces by May 2021 in return for a Taliban guarantee that Islamic terror groups would not operate from Afghan soil. The Taliban also ceased attacks on US personnel following the February 2020 settlement, marking the end of US combat deaths in Afghanistan.

This agreement vastly increased the Taliban’s apparent power and international legitimacy. One Taliban official even published an op-ed in The New York Times, pledging a “lasting peace” through which to “lay the foundation of a new Afghanistan.” At the same time, the Taliban intensified its attacks on Afghan military positions. A separate intra-Afghanistan peace process proved fruitless.

By late 2020, it was clear that the Afghan government was losing the information war, thanks to faltering institutions and relentless Taliban pressure. In October 2020, local officials reported that an errant Afghan air strike on a rural religious school had killed eleven children and their prayer leader. But the Afghan government contradicted the reports, insisting that no civilians had died. When a local spokesperson who had visited the surviving children in the hospital refused to echo the central government’s position, he was arrested and imprisoned. The spokesman felt “amid two stones,” as he later explained to The New York Times: caught between the Afghan government and the Taliban.

The spread of this attitude would mark the death knell for the Afghan government. For two decades, the Taliban had cast itself as the legitimate claimant to Afghanistan—no more corrupt or violent than the US-backed administration in Kabul. A growing number of Afghans came around to this view of the US-backed government, and by the time the Taliban began its blitzkrieg offensive in August 2021, many defenders had run out of reasons to fight.

These sorts of incidents only served to further erode the Afghan people’s loyalty to–and contribute to a significant loss of trust in–the US-backed government.

Not “Taliban 2.0”

The beliefs and objectives of the Taliban militants who streamed into Kabul this August are little changed from those held by the members of the group who fled the city twenty years earlier. Instead, what has changed is their willingness to use modern technology to realize their medieval ends.

Today’s Taliban understands how to disseminate its propaganda at scale and speed. It has come to appreciate how its English-language propaganda can be used to disarm and distract the international community—projecting a “moderate” face that helps obscure the massacres and violent retribution that have already begun under its reign.

This information conflict will not end with the Taliban’s control of Afghanistan. Already, anti-Taliban fighters are appealing to the West for military aid. Using pseudonyms, Afghan citizens have begun the first rumblings of an online resistance movement, intent on puncturing the Taliban’s claims of moderation and clemency and revealing the increasingly savage reality of its rule. The months ahead will bring a flurry of competing online narratives around Afghanistan, spanning numerous social media platforms and drawing in actors from around the world.

In 2021, this is a war that the Taliban is prepared to fight.

Emerson Brooking is a resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) and the co-author of LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media.

Further reading

Image: Taliban spokesman Suhail Shaheen leaves after a news conference in Moscow, Russia July 9, 2021. Photo via REUTERS/Tatyana Makeyeva.