One hundred and eighteen seconds after launching from southern Kazakhstan, Nick Hague found himself plunging toward Earth instead of heading for the stars. On October 11, the NASA astronaut was jettisoned from his shuttle, along with his Russian crewmate Aleksey Ovchinin, after one of the side boosters on their Soyuz rocket crashed into their second-stage boosters, rather than detaching from the system. Both astronauts safely returned to Earth, a welcome relief given the tragically long list of launch accidents.

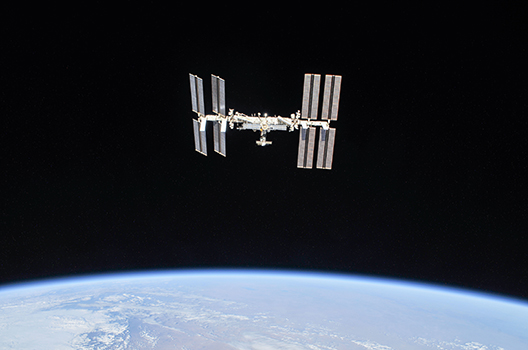

Hague and Ovchinin’s mission was already something of an anomaly in 2018. At a time when Russia and the United States spend most of their time preparing for conflict, space remains one of the few areas where both countries cooperate extensively. The two astronauts were headed to the International Space Station (ISS), an experiment in international cooperation launched twenty years ago on November 20, 1998, which has housed astronauts from more than ten countries. Ever since the end of the NASA Space Shuttle program in 2011, US astronauts have relied on Russian Soyuz rockets to get them to the ISS, a startling dependence given the tension between both countries.

NASA never envisioned this arrangement to be anything more than temporary as it hopes to send future US astronauts on US private launch systems as soon as sometime next year.

The problem with the October 11 launch came just a month after astronauts on the ISS had to plug a small hole in a Soyuz return vehicle docked at the station with “rags and other trash.” Signaling growing discord in the relationship, Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Roscosmos, the state corporation responsible for Russia’s space flight and cosmonautics program, shifted blame for the incident from potential assembly flaws on the Russian-made Soyuz craft to outrageous claims of sabotage by an ISS crewmember (Roscosmos and NASA now stress that no ISS crewmembers are being charged with any wrongdoing). NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine has been quick to dismiss suggestions that NASA has doubts about Roscosmos’ capabilities, but US-Russian space relations, once the bedrock of international space cooperation, have clearly hit bumps in the road.

The problems with the Russian Soyuz launcher come at a time when international cooperation on the final frontier appears to be in retreat. Space has been a cornerstone of US-Russian cooperation since the last days of the Cold War, but it may not be able to weather continued tension between Moscow and Washington, especially as NASA grows wary of Russian technical competence.

The United States has also shown the cold shoulder to the new kid in town: China. Since the mid-1990s, NASA has been required to seek congressional approval before undertaking any cooperation or contact with Chinese government officials. This rule has effectively limited NASA’s contact with the fastest-growing space power to discussions on civilian aerospace and earth science. While NASA continues to push for greater contact, the Trump administration’s growing displeasure with Beijing—along with very real concerns about intellectual property theft—makes it unlikely that Washington will warm to the idea of extensive cooperation with Beijing in space anytime soon.

At the same time, space has dramatically shifted from a domain for science and exploration to a vitally important theater for economic and military expansion. Satellite orbits are now vital economic resources for countries around the world and US President Donald J. Trump’s stated desire for a new “Space Force” reflects a very real understanding amongst militaries that the final frontier is as much of a potential conflict zone as air, sea, or land. With an endorsement from the National Space Council, a new space-focused military branch looks imminent for the United States, which could further push Washington away from cooperating with other space partners, especially potential adversaries China and Russia.

International cooperation has been the cornerstone of US forays into space since the early days of the Cold War. President Dwight D. Eisenhower specifically created NASA as a civilian agency in order to prevent the domination of space activities by the US military. NASA has nearly eight hundred active international agreements, which are vital for powering research in physics, chemistry, medicine, biology, and environmental science. This cooperation will be vital in addressing both space specific problems, such as increasing satellite traffic and dangerous orbital debris, but also in addressing close-to-home threats like climate change and natural disasters.

Despite incredible leaps in technology, humanity’s desire to explore and utilize space still requires vast amounts of wealth and expertise, making the pooling of resources with international partners vital to achieving missions. Certainly, NASA will continue its vast cooperation with its natural partners such as Europe, Canada, and Japan. Indeed on November 16, NASA celebrated the arrival of a European-built service module, which will power NASA’s Orion spacecraft in development for possible human exploration of Mars.

But the promise of the International Space Station, and indeed much of the cooperation in space, was the ideal that geopolitical competition could be forgotten beyond Earth’s atmosphere. For now, this international cooperation remains in place, as at this moment a German, an American, and a Russian are living 250 miles above the Earth, entirely dependent on each other and cooperation between their governments for their survival. As space becomes more and more intertwined with the global economy and geopolitical competition, humanity risks abandoning the spirit of cooperation and extending the conflicts of the Earth to the stars.

David A. Wemer is assistant director, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

Image: The International Space Station (ISS) photographed by Expedition 56 crew members from a Soyuz spacecraft after undocking, October 4, 2018. (NASA/Roscosmos/Handout via REUTERS)