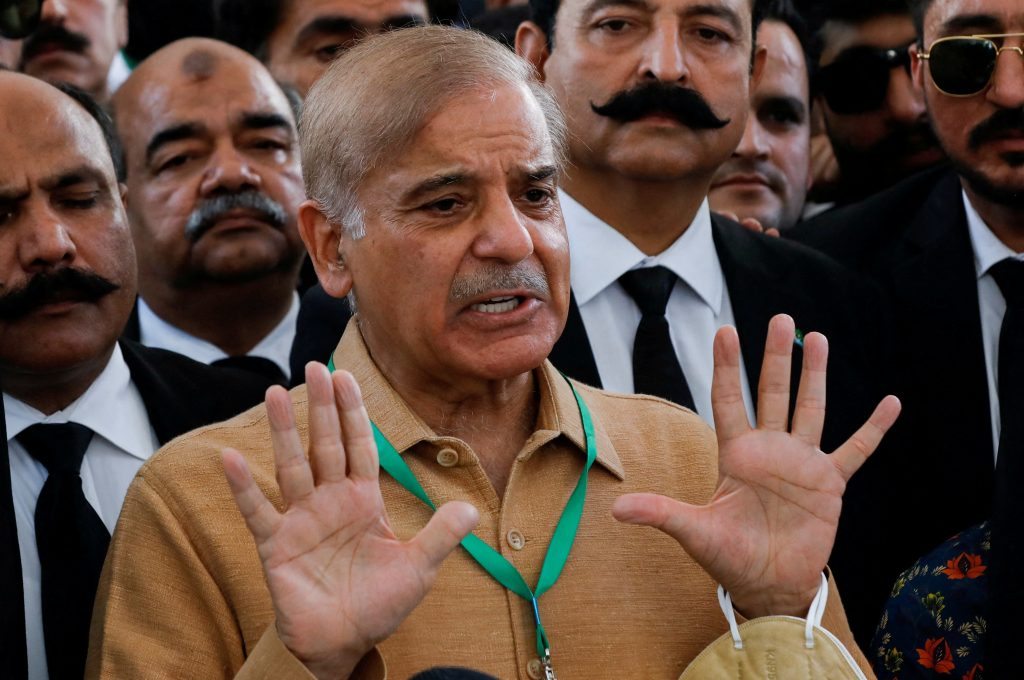

There’s a new bowler in town. Pakistan’s parliament removed cricket star-turned-populist Prime Minister Imran Khan from power on Sunday and, a day later, installed opposition leader Shehbaz Sharif, the brother of former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. As Khan’s supporters rally in the streets and the ousted premier hopes for a swift return to power, Sharif is working on forming a government, tackling soaring inflation—and guiding his country out of a political crisis. We reached out to Pakistan-based experts for their thoughts on Sharif and what comes next in the pivotal South Asian nation.

Jump to an expert reaction:

Amber Rahim Shamsi: Can Khan’s ‘agitational politics’ mount a comeback?

Farieha Aziz: An opportunity to bring back free speech

Ammar Habib Khan: A brewing economic crisis requires a steady hand

Can Khan’s ‘agitational politics’ mount a comeback?

The big question for the incoming Shahbaz Sharif-led coalition government will be when to hold elections. The timing will depend on political opportunities and costs, the economic agenda, and administrative delays. The current parliamentary tenure—during which two prime ministers were elected—comes to an end in summer 2023.

Ousted Prime Minister Imran Khan is pushing for early elections. He is betting on riding a sympathy wave triggered by his narrative of “regime change” through a foreign conspiracy, a notion hyped through rallies. His party also hopes to build pressure for snap polls through resignations from the lower house of parliament. Khan is hoping agitational politics will be enough to overcome the loss of military support and political allies.

The Sharif government will want the agitations by Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party to die down as it aims to pick the next army chief before November and avoid the political fallout from the persistent inflation and high taxes that marked the Khan government’s economic management. The government-allied parties also have a legislative agenda to prevent the forms of electoral rigging they condemned in 2018, which included the failure of the electronic results transmission system and alleged irregularities in counting votes.

There are also legal and administrative impediments to early elections—constituencies will need to be redrawn based on a new census due next year. The 2017 census was marred by legal challenges mounted by several political parties that are now allied with Shahbaz Sharif.

The last government alliance between the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) lasted less than a year. The stability of this coalition between the two parties will depend on its ability to see through a common legislative agenda with an eye on the next election.

Throughout the hybrid regime experiment headed by Khan, the army had to fend off political attacks from the Pashtun nationalist movement called the PTM and subsequently from PML-N supremo Nawaz Sharif and his daughter. Now an army that is sensitive to its cohesion, morale, and domestic image will need to contend with an angry Khan and his supporters.

There were several reports the evening that Khan was ousted that he had tried or threatened to engineer a military coup. The next day, his supporters were on the streets in large numbers calling out the army chief, the judiciary, the government alliance, and the United States, which is accused of facilitating Khan’s removal.

A number of pro-PTI social media users who have pushed trending hashtags against the army have been arrested, but with more PTI rallies planned in the coming weeks, matters could escalate. It remains to be seen whether Khan, who has been careful not to directly accuse the army chief of collusion so far, will go his rival Nawaz Sharif’s way and openly name the military leadership or, more cunningly, continue to let his support base do the talking.

— Amber Rahim Shamsi is the director of the Center of Excellence in Journalism at IBA Karachi.

An opportunity to bring back free speech

In a tweet on April 9, now Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif congratulated media outlets and civil-society organizations for their efforts in getting the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) Amendment Ordinance—an executive order by the Imran Khan government to restrict free expression—declared unconstitutional by the Islamabad High Court. He also acknowledged what he called “unprecedented curbs on freedom of expression.”

Undoubtedly the striking down of Khan’s amendments to PECA is a welcome step. But the court also struck down language from the 2016 law, which was introduced by Sharif’s PML-N, after a challenge brought by journalists who were victimized by the law.

It is the 2016 law—bulldozed through parliament by the PML-N as it enjoyed a majority—that was used to clamp down on political opponents, dissidents, activists, and journalists. Khan’s PTI put the law toward the same end and sought to expand its scope, though that effort was challenged and thwarted before it could be used.

Going forward, the hope is that the incoming regime will have learned its lessons and now understands what it means to be discredited, kept off air, be targeted with malicious cases, and prevented from organizing and expressing themselves through ‘legal’ manipulations and extra-legal means—whether online or offline. The expectation of civil society is that the new government will not only put an end to all such policies and practices, but they must ensure illegal detentions of critics do not remain the norm. To do so, the new coalition must withdraw all politically motivated cases under PECA and other laws, take down the social media rules created under PECA, put in the legislative work to undo laws such as PECA, refrain from using media and telecommunications regulators in a partisan manner, and be open to feedback and criticism. That means hearing out the same civil-society groups and media outlets that the prime minister congratulated on what they require to really end Pakistan’s culture of censorship and self-censorship.

—Farieha Aziz, is a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

A brewing economic crisis requires a steady hand

A commodity supercycle of rising prices that refuses to take a breather, a global transition toward hawkish monetary policy, and the vulnerability of Pakistan’s economy to food and energy prices are going to add a layer of complexity in a volatile political environment. If the populist economic decisions taken by the outgoing government are not reversed, they are going to have an adverse impact on fiscal and external deficits, which would constrain the new government’s capacity to drive meaningful change.

The first order of business ought to include a phase-out of energy subsidies and ensuring the availability of food staples at affordable prices, which is as much of a supply-chain issue as it is a pricing issue. A phase-out of energy subsidies would lead to a spurt in inflation, followed by second-round effects as goods and wages are repriced. How soft or hard the landing will be depends on whether monetary policy is more proactive or reactive. A resumption of Pakistan’s International Monetary Fund program and securing external funds from key partners would be critical to avoid an external funding crisis, given the excessive reliance of the economy on imported food and energy. On the economic front, the next two quarters will be challenging, and navigating them without any populist uprising backed by the opposition can be deemed a short-term success.

—Ammar Habib Khan is a non-resident senior fellow at the South Asia Center.

Further reading

Thu, Mar 24, 2022

As no-confidence vote looms, Pakistan’s democracy faces key stress test

SouthAsiaSource By

Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan faces a no-confidence motion in the country’s National Assembly (the lower house of its Parliament).

Mon, Mar 28, 2022

Pakistan: The next great infrastructure connector

Issue Brief By

Pakistan sits at the crossroads of the abundant resources of Central Asia and the Middle East, and the lucrative markets of China and India. It therefore has the potential to play a significant connecting role, one that enables broader regional interdependency while boosting domestic economic prospects.

Tue, Mar 15, 2022

A terror redux in Pakistan?

SouthAsiaSource By

The recent surge in terror attacks may be a harbinger for another wave of militancy in Pakistan, which it will have to fight alone.

Image: Leader of the opposition Mian Muhammad Shehbaz Sherif, brother of ex-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, gestures as he speaks to the media at the Supreme Court of Pakistan in Islamabad, Pakistan, on April 7, 2022. Photo by Akhtar Soomro/Reuters.