When top US and Indian trade officials met in New Delhi in late November, they managed to agree to a sweeping joint statement that reflects the growing friendship between their governments. US Trade Representative Katherine Tai and Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal even hit it off on a personal level, I’ve been told by those at the table—and with the able assistance of their senior officials, set an ambitious timetable of goals for 2022 to ensure no stone was left unturned in identifying the full range of trade issues to be addressed in the future. Those include agriculture, manufacturing, digital trade, trade-unfriendly regulatory measures, worker rights, and environmental policies.

But what lies ahead in this trade relationship is the real test—which the two sides could easily fail, vaulting both back to the days when neither prioritized their trade ties. My own instinctive cynicism from experience as a trade negotiator in both bilateral and multilateral talks tells me that’s a distinct possibility. If that happens, they’ll continue to diverge on an array of issues, from measures to protect domestic interests and trade-restrictive regulatory trends to broader perspectives on climate, labor, and human rights that have implications for trade relations.

Yet I’m also cautiously optimistic, particularly on the bilateral front. The stark reality is that the United States and India cannot build out a robust, twenty-first century strategic partnership unless they can better align their economic and trade relationship. In the not-too-distant future, they’re likely to be the first- and third-largest economies in the world. That fact alone, along with their emerging joint commitment to set a course for a bright future for the Indo-Pacific area, requires that this trade relationship becomes a top priority for each country.

This brings me back to the modest, but important, accomplishment of Tai and Goyal in reinvigorating the bilateral Trade Policy Forum. The joint statement from this first ministerial meeting could easily fade into the ether, like so many before it, absent a series of immediate and concrete steps. These should be strongly supported by the foreign- and strategic-policy teams on both sides while allowing the trade teams to do their work. Trade policy requires coordination across all government agencies and must be informed by the perspectives of stakeholders across the spectrum—but is otherwise best left to the experts.

Here’s what I suggest both sides should do:

- Begin work immediately on the full range of digital and health trade issues and seek specific outcomes, even if incremental, throughout 2022. The regulatory approaches of the United States and India have taken divergent paths in recent years, and the longer this continues, the greater the tensions will be (and more discordant the policy misalignments) in the trade relationship. On the digital front, there should be a concerted effort to identify common ground on data localization, privacy, fair competition among e-commerce platforms, and reasonable guardrails for social media responsibilities. On the health front, there needs to be a better understanding of international best practices on regulation, price controls, public procurement, and the protection of intellectual-property rights.

- Solve the major outstanding issues left over from the failed effort to strike a bilateral trade deal in 2020. These include more access for agricultural exports, such as lifting India’s ban on fuel ethanol imports (which surely is non-compliant with World Trade Organization rules), the pricing of medical devices, and a strong commitment on the reinstatement of India’s Generalized System of Preferences benefits, which the United States suspended in 2019 over concerns about India’s closed market. Near-term, market-opening results should include the reduction of the growing number of technical barriers to trade that have been cropping up in recent years as India has veered toward national standards and testing requirements that are at odds with international alignment.

- Venture into frank discussion on emerging trade issues, such as labor and the environment and good regulatory practices, but keep immediate expectations low. Labor and the environment are priority areas for the Biden administration’s trade policy, as Tai frequently reminds us, and they deserve appropriate attention. While India may be allergic to discussing these issues, out of fear that they may be an excuse for new US trade restrictions, I know from my own experience that there can be tremendous scope for trade negotiators to cooperate on pressing issues. But they should also lose no time in taking up work on good regulatory practices, which involve the basics of transparency, predictability, and accountability in developing new regulations. This promises to be an area that provides a positive impetus for bilateral work (just as trade facilitation has been).

- Achieve early results on trade in services, which have been neglected in bilateral discussions in recent years. This may not be a full-blown free-trade agreement on services—that should wait for the launch of a comprehensive free-trade negotiation—but there certainly is scope for sectoral market-opening commitments. For example, more progress is due on insurance and education, as well as on greater predictability in the US administration of H1B visas for temporary foreign workers.

- Finally, be explicit on a conditional plan to engage in free-trade agreement negotiations. While the circumstances are not yet ripe for embarking on talks in the near future, progress on the aforementioned issues could create those circumstances sooner than later. This plan would be conditional in the sense that continued failure to achieve market-opening results will delay the day for taking up a free-trade agreement. But it’s important not to waste time in articulating this vision. That, in itself, can be an impetus to achieving short-term goals.

During my time in government, I played a role in both the highs (such as the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement in 2013 and an agreement to phase out agricultural export subsidies in 2015) and lows (the failure to conclude a first-ever bilateral trade deal during the Trump administration) of the US-India relationship. And I remain committed to cheering these efforts on.

But the relationship deserves more cheerleaders than simply fading former trade negotiators. The respective trade ministries, with encouragement from their foreign-policy and national-security counterparts, need to prioritize it. Stakeholders in both countries need to be vocal about their goals but also realistic in their expectations. Academics and think tanks will need to continue playing important roles.

One key stipulation, however, is that the goal of a comprehensive trade relationship between the United States and India will not be reached via ongoing Indo-Pacific initiatives, such as a regional digital trade agreement. These are important, but bilateral trade must be addressed in true bilateral fashion—with the United States and India alone at the table. This formula will undoubtedly experience its share of frustrations on both sides, but the two can emerge as stronger allies with much better prospects for cementing their economic paths in a mutual vision for the future.

Mark Linscott is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center and the former assistant US trade representative for South and Central Asian affairs, and WTO and multilateral affairs.

Further reading

Thu, Sep 30, 2021

Why the Quad summit was a strategic success

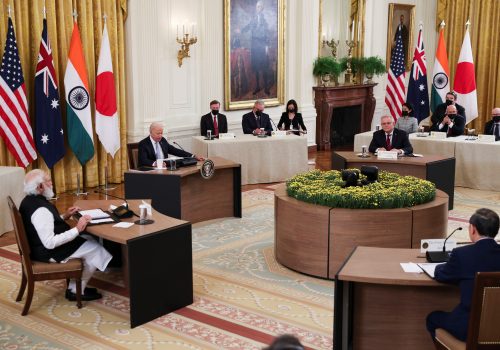

New Atlanticist By Ash Jain

While its specific outcomes may have been relatively modest, the summit successfully laid the foundation to advance three strategic US goals: countering China, aligning India, and revitalizing alliances.

Wed, Oct 6, 2021

Trade could transform US-India ties

New Atlanticist By Mark Linscott

Washington and New Delhi need a joint vision for a deeper, broader, and more integrated economic relationship.

Fri, Dec 17, 2021

The multilateral trade system isn’t what it used to be. Here’s why it still matters.

New Atlanticist By Mark Linscott

The WTO may have its fair share of problems—but it still serves a valuable purpose.

Image: US Trade Representative Katherine Tai and Indian Minister of Commerce and Industry Piyush Goyal pose for in New Delhi, India, on November 22, 2021. Photo by Adnan Abidi/Pool/File Photo/REUTERS