Although the United States and China have increasingly confronted each other on issues such as trade, 5G infrastructure, and the expulsion of journalists, both sides continue to insist that they are seeking a positive relationship. But mutual trust and friendly bilateral relations are unachievable as long as Beijing and Washington view each other as a potential threat to their national security or interests. The coronavirus pandemic has fueled these perceptions, with US officials increasingly concerned about how failures in Chinese governance could impact the United States, while Beijing has pushed back on criticism of its ideological and political system.

Using data from 336 announcements and documents published by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs from January 1 to May 12, 2020, as well as statements issued by US government officials, it is clear that the pandemic has worsened the threat perception by both sides, placing even more obstacles in the way of positive US-Sino relations.

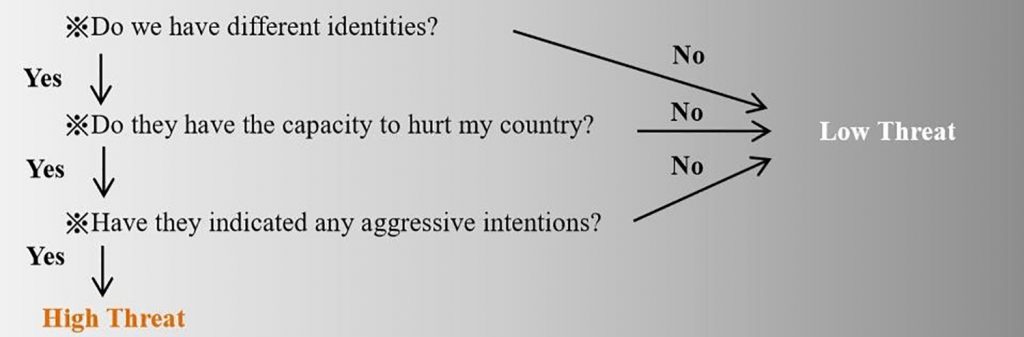

The perception of a “threat” is essentially a sense of insecurity constructed by interactions between subjects under certain circumstances and conditions, and dependent on factors such as history and norms. As shown in Figure 1, the level of threat to the other can be analyzed through the three aspects of identity, capacity, and intention.

Washington sees Beijing’s governance as a threat

Although the United States and China jointly established mechanisms for diplomatic security, economics, law enforcement, cyber security, social sciences and humanities, and other security dialogues in 2017, Washington’s perception of potential threats from Beijing is outlined in the 2017 National Security Strategy and 2019 National Defense Authorization Act. The documents clearly identify China as a revisionist power and strategic competitor, and also use many performative utterances such as “steal” and “aggression” to emphasize a rising China’s intention to threaten the United States.

It is undeniable that the differences in political systems and ideology, combined with the historical experience of the Cold War, created the basis for the rift between the United States and China. In recent years, however, China’s overall national power has increased, and it has gradually become capable of militarily, economically, and culturally challenging the United States. In terms of identifying the threat posed by China, the United States has focused on economic and trade issues in relation to national security, while it has rarely mentioned national governance as a key concern.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed potential structural flaws in China’s internal governance, whose failure in containing the virus has heavily impacted the US economy and healthcare system. On May 6, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo publicly criticized the Chinese government for its lack of transparency and attempts to conceal early signs of the outbreak of the coronavirus. US President Donald J. Trump told reporters at the White House on May 7 that the global pandemic was a worse “attack” than Pearl Harbor, accusing China of failing to do its duty by allowing the virus to spread globally. The United States Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) also issued a joint announcement on May 13 accusing the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) of stealing US vaccine research data, posing a “significant threat” to the United States’ response to the epidemic.

The term “securitization” in international relations refers to the subjective assessments of perceived danger to national security which compels states to “securitize” non-defense sectors to protect them from foreign influence or attack. The statements by US officials have in essence shown the “securitization” of the public health field, as Washington now fears the potential disruption Beijing can cause to the US healthcare system. At the core of this new perception is the growing concern about the ability of the communist system and the Chinese state to govern effectively and prevent crises like this one in the future.

Beijing’s response: China is a model to follow

Since the founding of the CCP the concept of “peaceful development” (和平發展) has been at the core of its diplomatic theory. Throughout his tenure, President Xi Jinping has sought to actively participate in global institutions, using “multilateralism” to rebut those who see Beijing as “anti-hegemonic” and a potential threat to the international order. In terms of relations with Washington, the CCP clearly understands that the United States is still the world’s superpower and has a certain degree of influence in the world, and there is still a gap in the comprehensive national strength between China and the United States. Therefore, China still needs to cooperate with the United States in many aspects. Despite Washington’s increasingly bellicose language, the CCP has sought “non-conflict and confrontation” and “mutual cooperation” through its statements in recent years.

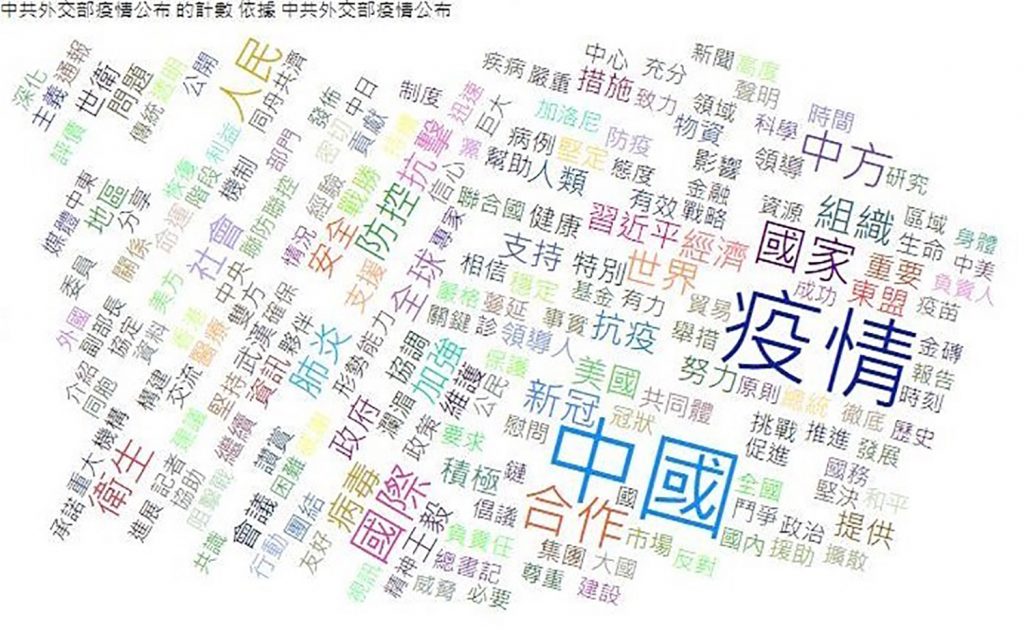

This approach is also evident in Chinese statements on the coronavirus pandemic, but the tone and substance of Beijing’s rhetoric changed dramatically throughout the crisis. Chinese officials utilized “neutral” diplomatic terms in an effort to shirk the idea that China was exclusively responsible for the outbreak. The most mentioned words in the documents are “China,” “cooperation,” “international,” “unity,” “humanity,” “health,” “world,” and other collective nouns. Most of the content of the documents is used to depict China as an international model for epidemic resistance, and to bolster the image of Xi Jinping as leading China’s successful coronavirus response.

As China’s domestic epidemic was brought under control, however, China’s diplomatic strategy turned into an offensive campaign. Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Lijian Zhao shared messages on Twitter in March implying that the virus originated in the United States. Chinese diplomats in various countries have changed their traditionally prudent and conservative language, proactively demonstrating their new style of confrontation, and vigorously publishing articles in various countries to defend China’s position with sharp and threatening language. The English version of the Global Times of the CCP stated on Twitter that “the days when China can be put in a submissive position are long gone. As Western diplomats fall into disgrace, they are getting a taste of China’s “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy.”

Beijing’s sensitivities to Washington’s attacks on China’s governance system are also reflected in various texts of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The CCP’s targeted attacks on the United States in the early stage of the epidemic mostly called on Western countries to “respect the political system chosen by the Chinese people” and avoided using controversial terms such as “ideology.” The statements decried “prejudice against China and its ideology” to shape the role of “China as a victim,” and made rationally-worded calls for strengthening international cooperation and avoiding intensification of its antagonistic relationship with the United States. In an attempt to shift attention away from its political system, the CCP has defined the epidemic as “a sudden epidemic disease, an unprecedented global crisis.”

After coronavirus: The competition continues

In the post-COVID era, US-China relations will enter a more difficult phase. From the analysis of the diplomatic vocabulary used by the two countries during this period, it is clear that Washington no longer sees China simply as a rival, but as a clear threat to its security, economy, and now even its society. In contrast, China still defines itself as a seeking “partnership” with the United States, but has shown itself more willing to hit back rhetorically at Washington and has grown concerned at US criticism about Beijing’s political system. China’s response to these attacks—publicizing its national experience in the fight against COVID-19 as a model for others to follow and touting its centralized state system—could further deepen the US-Sino rift. The history of ideological confrontation during the Cold War will make it difficult for Western countries, mainly the United States, to back away from ideological challenges.

Coronavirus has accelerated changing perceptions in Washington and Beijing and deepened the ideological confrontation between the two different political systems symbolizing “democracy” and “centralization.” While both countries had hoped to forge a positive bilateral relationship, the coronavirus crisis has only driven this possibility further away.

Chang-Ching Tu is the Taiwan senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and assistant professor at the ROC (Taiwan) National Defense University.

Further reading:

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping is seen on a screen during the opening session of the National People's Congress (NPC) at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China May 22, 2020. REUTERS/Carlos Garcia Rawlins