Pakistan is at a precarious point in its faltering return to democratic order, after yet another extended period of military-dominated rule that has left its bureaucratic system and civilian institutions stunted. Its polity and society have undergone rapid change, with countervailing forces emerging to counter the military’s overwhelming power. Though political parties remain weak and divided, the democratic impulse appears to be taking hold in civil society, as illustrated by the emergence of active media and social networks combined with an increasingly assertive judiciary. Although elements in the intelligence services still occasionally attempt to control the media and political actors, the military has neither the will nor the capacity to mount a coup, nor the ability to effect major political change.

Public opinion in the U.S. and views on the Hill are heavily biased against a cordial relationship with Pakistan, reflecting years of mistrust of Pakistan’s role in the Afghan war. Pakistan’s two-handed approach to the Afghan Taliban, taking U.S. assistance and payments for military operations in the borderlands while allowing selected groups of Afghans free movement to and from Afghanistan, hinders the Administration’s ability to provide more military aid to Pakistan. On the Pakistani side, suspicions that the U.S. has shifted its stance away from Pakistan and towards India, with the ultimate goal of defanging Pakistan’s nuclear weapons capability, make it nearly impossible for U.S. officials and aid representatives to operate freely inside the country. Public denunciation of the drone campaign by government and civil society actors fuels antipathy toward the U.S. Pakistan’s Parliament has echoed these fears in its calls for protection of national sovereignty and for greater controls and taxes on coalition supplies going through Pakistan to Afghanistan.

In such an environment, cutting our losses and walking away from the region, and specifically from Pakistan, might seem an obvious —and popular—choice. But such a decision would entail significant longer-term costs. Not only will the withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan require ground and air lines of communications via Pakistan, our Afghan allies will continue to require supplies and air support via Pakistan. Cutbacks in air and military support would be disruptive at a critical stage when their security forces are being prepared to take on more ground operations. Without air support, those might be jeopardized and Afghan morale would plummet.

What happens inside Pakistan affects its immediate neighbors— India, China, Iran, and Afghanistan—instantly, and more distant countries over time. A precipitous U.S. withdrawal could lead to heightened conflict in the borderlands of Pakistan, allowing the Pakistani Taliban and their Punjabi allies to use the Federally Administered Tribal Areas as well as contiguous Afghan territory as sanctuaries in fighting the Pakistani army and state. It would give extremist elements inside Pakistan greater voice and control over public discourse in civil society and the military.

Latent anti-U.S. sentiment in the military, especially among younger officers and perhaps the soldiery, is indicated by the fact that some of the attacks against General Pervez Musharraf and military headquarters included lower-level personnel from both the army and air force.

Large portions of public opinion in Pakistan view the U.S. civil nuclear deal with India as an anti-Pakistan move, and the absence of any attempt to engage Pakistan in a similar dialogue as proof of an entrenched anti-Pakistan bias. A shift toward India, if this were to accompany U.S. withdrawal, would strengthen conspiracy theorists inside Pakistan in their belief that the U.S. always intended to compromise and weaken Pakistan.

The U.S. has been and remains the largest supplier of assistance to Pakistan, both civil and military, and via the International Financial Institutions (the International Monetary Fund, World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, in particular). But our aid program has been sporadic and tied to regional or global aims in a manner that has led Pakistanis to become wary of U.S. ties, understandably regarding their relations with China more kindly. The U.S. has an opportunity now to change that dialogue and move toward a longer-term relationship with Pakistan as the center of gravity of U.S. engagement in the region, rather than as an after-thought relative to emerging regional crises or changing global policies.

What needs to be done?

Firstly, the U.S. should expand its approach to Pakistan by working with regional partners, many of them Pakistan‘s friends, to ensure a stable Pakistan and a steady U.S.-Pakistan relationship. Building on the Pew Global Attitudes Poll results that regularly indicate that six out of 10 Pakistanis polled want better relations with the U.S., we can create a steady, longer-term relationship that is not tied to short-term goals.

Helping Pakistan to help itself should be the key to this new relationship. If Pakistan’s people and government want to improve governance and provide jobs and education to their growing population of nearly 200 million, then the U.S. should make that its aim too.

Combining our resources with those of the United Kingdom in the education sector, as has been done recently, offers a good model. Working with China in building infrastructure and the energy sector could bolster Pakistan’s ability to get out of its economic hole. Open borders with India for trade and the movement of people would help to remove decades of fear and hostility on Pakistan’s eastern border. Our new strategic relationship with India enables us to use moral suasion on India to show “strategic altruism” and give Pakistan the breathing room for its economic and political development. A moratorium on active Indian and U.S. intelligence operations inside Pakistan would most likely win Pakistan’s trust in this endeavor.

Secondly, the U.S. should review and rebalance its policies on aid to Pakistan. Specifically, U.S. assistance to Pakistan can gain from the multiplier effect of aid from IFIs that Pakistan sorely needs and is more willing to accept. U.S. support in the boards of these institutions can help Pakistan to garner the resources it needs to restructure its economy. The U.S. can also help in persuading Pakistan’s government and bureaucracy to move faster on the reform path.

An Aid to Pakistan Club may be one way of doing this. The U.S. Congress may be able to help the Pakistani Parliament, via direct parliamentary contacts, to allow Pakistani parliamentarians better understand economic issues and the value of a reform agenda that has been crafted inside Pakistan but still lacks support from its politicians. Congress could thus come to be seen as a partner of Pakistan, rather than the hectoring controller of the U.S. aid purse that it is often perceived to be.

A greater role for civil society

Thirdly, U.S. aid and a strengthened relationship with Pakistan should be made contingent on actions by Pakistan to allow civil society and business to play a greater role in setting it on the path to economic and political stability. The civilian government needs to show a desire and ability to re-establish its control over government, instead of outsourcing decision-making to the military. Once the military recedes into the background, relinquishing its role as default drafter of policy on India, nuclear policy, Afghanistan, and U.S. relations, the U.S. could commit, under an agreed military aid program, to improve Pakistan’s ability to combat insurgency and defend its borders with a more mobile and better-equipped army and an improved and integrated police force.

Pakistan is both a strategic ally and a potential bulwark of stability. If its people and government are prepared to align and commit themselves to fulfilling that potential, the United States must be willing to help them.

Shuja Nawaz is director of the South Asia Center at the Atlantic Council. He is the author of Crossed Swords: Pakistan, Its Army, and the Wars Within. This piece is taken from the Atlantic Council publication The Task Ahead: Memos for the Winner of the 2012 Presidential Election.

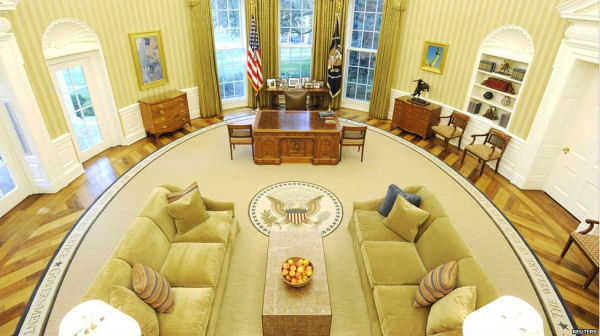

Image: oval-office-2010-new-overview.jpg