March 14, 2020

The price of great power politics

This report recap is part of the AI & China: Smart Partnerships for Global Challenges project, focused on data and AI. The Atlantic Council GeoTech Center produces events, pioneers efforts, and promotes educational activities on the Future of Work, Data, Trust, Space, and Health to inform leaders across sectors. We do this by:

- Identifying public and private sector choices affecting the use of new technologies and data that explicitly benefit people, prosperity, and peace.

- Recommending positive paths forward to help markets and societies adapt in light of technology- and data-induced changes.

- Determining priorities for future investment and cooperation between public and private sector entities seeking to develop new technologies and data initiatives specifically for global benefit.

@acgeotech: Championing positive paths forward that nations, economies, and societies can pursue to ensure new technologies and data empower people, prosperity, and peace.

Summary of the Berlin Roundtable on China & AI — November 7, 2019

After having been awarded a Rockefeller Foundation grant in the fall of 2019, the Atlantic Council started the project of evaluating the implications of China’s mastery of emerging technologies on politics, society, and international relations. The endeavor started with workshops in Paris and Brussels where high-level participants had the opportunity to exchange views, consult about disagreements, and map out paths towards potential global cooperation — always with a special focus on China’s role as a global citizen and the country’s use and development of artificial intelligence.

The third meeting of the series was co-hosted by the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) and held in Berlin on November 7, 2019. Unlike previous gatherings where a majority of participants represented government institutions, the roundtable in Germany brought together business- and private-sector representatives. Together with policy experts, they discussed the emergence of new technologies, the rise of China, and the implications of a global AI race. The meeting, which was held under strict Chatham House Rules, was thereby the last Eurocentric roundtable before the journey continued eastwards and an Atlantic Council delegation visited China in early January 2020.

Discussions started with one participant challenging the notion that IT has always been and always will be global. “AI is important, of course, but it is only a certain aspect of the IT revolution. There is this original idea that IT must be global, but is that really true? Or is it mainly because of the unipolar moment that the United States defined after the end of the Cold War? What happens if we start looking at completely different IT stacks, with different regions implementing different regulations and technologies?” The idea of tech regionalism caused some push back from others who argued that “a regional approach might work with regard to other IT systems, but AI is truly global. Almost all developments are happening internationally, with world-wide applications and consequences.”

The warning of “technological regionalization,” however, introduced an interesting thought experiment, especially since modern technologies seem to have become the new playing field for great power competition between the United States and China. In such an environment, the lack of essential EU funding and leading European tech companies, missing unity among EU member states, and a difficult environment for the collection and application of data are all indications that Europe is falling behind. There might be an ongoing debate about necessary investment strategies, but “looking at emerging technologies from a foreign policy perspective has never been a tradition, neither in Germany nor in the European Union — and that only started to change recently,” one participant explained. More discussants worried that Europe is increasingly being challenged by the new political reality, and risks becoming even more dependent on external players, if it does not develop a stronger policy stance on emerging technologies all together.

An Ever Increasing Rivalry

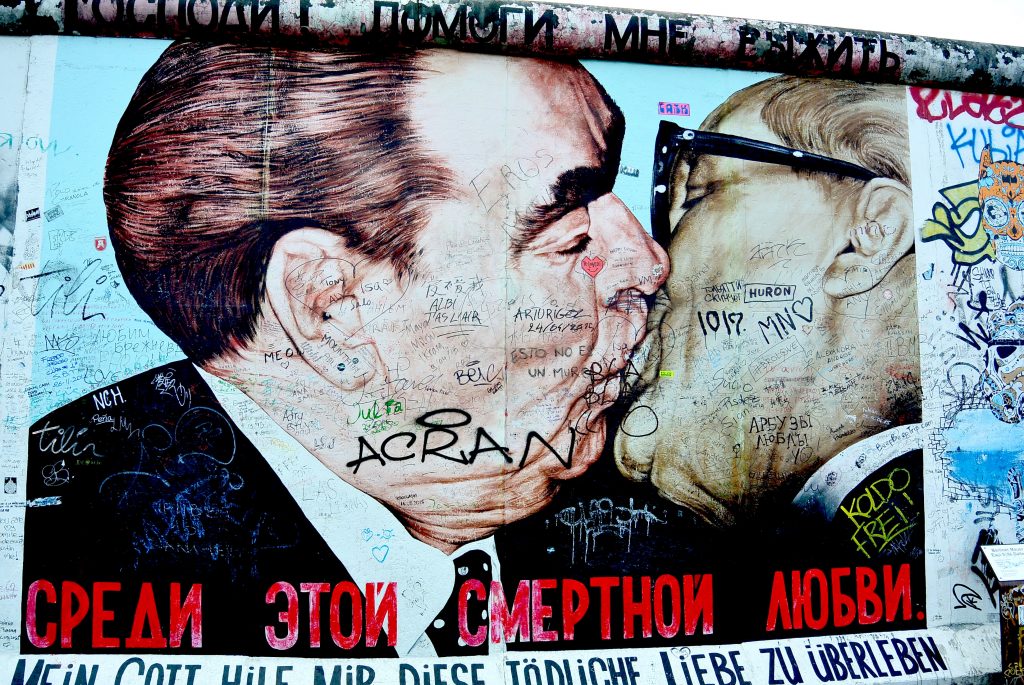

For a long time, there were advocates in both the US and China who argued for broader, international coalitions — policy stands that would have ensured greater convergence on the norms and regulations for developing and implementing AI as well as for other technologies. This more constructive notion, however, changed significantly, one participant warned: “The United States and China have entered a rivalry that is beyond personality or nationalism. American decision-makers feel as if their country’s supremacy is being threatened by a rising China. To put it bluntly, Washington is fearful of losing its primary status.” The expert continued by alluding to the securitization of technologies. “Technology is shifting from the area of manageable competition to an arena of intense rivalry. We see that particularly with regard to AI that is now regarded as central to national security concerns. Technological rivalry has become integral to warfare, and the fear in the Pentagon is that the United States may not be able to dominate in the way the country used to lead in other fields.” Of course, even rivals can cooperate and war is not inevitable, but subsequent discussions made clear that many believe the potential for unintentional conflict exists. “China has never confronted a rival or competitor like the United States, but neither has the US — today’s China is far from being the Soviet Union of the past and Cold War analogies are therefore short-sighted.”

Particularly worrisome for participants in Berlin was the lack of understanding between Washington and Beijing. As an example, one discussant explained that Chinese never refer to the ‘rise’ of the People’s Republic (PRC), but rather see it as a ‘restoration.’ He continued by saying that Beijing might have been able to play at the high table, “but always being told who owns the casino resembles a humiliation, rather than a fair equilibrium.” Furthermore, “Chinese decision makers, even Deng Xiaoping, never thought the convergence theory is applicable, because the Chinese concept of legitimacy and order is obviously very different to Western-style liberalism.” Unlike the Western notion of any government having to achieve legitimacy through democratic accountability, the key point in China seems to be whether the policy system is delivering economic prosperity, social stability, and constant progress. “For the Chinese government, emerging technologies are seen as a useful tool for preserving domestic stability on the one hand, and increasing defense capabilities on the other.” Such military uses especially worry US decision-makers who think that they “need to get tough on China before it is too late.”

Europe’s Dilemma

According to most participants, subsequent decoupling efforts, especially in the technological realm, would come at a high price and put European states in a “complicated” situation. “Of course, a human-centered and values-based AI approach is important for Germany and positions us closer to the United States,” one think-tank representative emphasized, when referencing the EU’s recent GDPR privacy regulation — a policy that exemplifies Europe’s interest that the internet, and social media platforms in particular, do not override individual rights and privacy. Following suit, many participants saw the GDPR as a success story in which Europe’s market power was used to enforce norms with wide ranging implications, visible both in the United States and China.

However, there was also worry about Europe’s growing economic dependency on the PRC: “China is a huge market and therefore very important for European and especially German businesses. I can’t stress enough that the idea of having to choose sides is incredibly worrisome and needs to be avoided at all costs. Already today, China creates guidelines that turn out to be incompatible with international standards. If you want to sell a computer to the Chinese market, for example, you need to include a Chinese made control program (CPM). [Western] companies already have to make choices which side to follow.” Discussants agreed that in a globalized world, economies are so intertwined that “choosing sides” will be very painful for businesses, particularly in export-oriented countries. Circumstances that go some way to explain Europe’s reluctance to join in with the United States’ emerging anti-China doctrine.

Some even went one step further and argued for digital sovereignty. “From a European perspective, you can neither trust the Americans nor the Chinese. We do not have digital autonomy, which is the main problem. In a situation of global mistrust and ineffective international institutions that weren’t built for today’s world, it might already be too late for Germany to become an effective player.” Even if there are areas where European companies develop cutting edge technologies, the fact that the EU allegedly doesn’t have many other strengths in the global AI race worsens the situation. “We lack necessary ecosystems, fail to adopt our education policy, and grapple with a lot of inadequate infrastructure,” one rather pessimistic participant concluded. “Our only strength is the industrial application of data and artificial intelligence, but even that status is challenged by the Chinese.”

Societies under Pressure

One would think that the magnitude of potential disruptions for society as well as the speed at which modern technologies are developing would incentivize governments to cooperate. However, quite the opposite is happening, and discussants worried that the world is moving into a scenario “where bipolarity and political forces will dictate economic activity.” Particularly evident in Berlin was the difficulty of moving from diagnostics to strategy. Who will take up the reigns of regulation, if the world has come to an impasse, where rivalry is the dominating force? Can businesses step up and lead the way towards technological cooperation, while braving political storms at the same time?

A variety of scenarios was discussed, and participants highlighted the need for pragmatism. By focusing on value chains, one academic suggested that norm setting and oversight “might be areas of successful international collaboration.” She added, that such an endeavor, “of course, requires a sophisticated understanding of the very nature of AI, other emerging technologies, and the collection of necessary data.” Others broadened the focus and emphasized the need for extracting raw materials in a sustainable and collaborative way, avoiding a new battle over semi-conductors, and jointly securing supply chains in a world of increasing disarray. “Before speaking about potential cooperation on the international stage, Germany as well as the European Union have to define what they want. Despite the EU’s preferred third way approach, there is certainly a lack of strategy. Long term planning, however, is needed more than ever,” one participant emphasized. When China is striving for global leadership by 2030 and the United States is trying to protect its superior role, Europe risks getting stuck in the middle, constantly under pressure to choose sides all the while scared of being crushed in a fight that is likely to only know losers.

Similar to other sensitive policy-areas, there is no “black-and-white approach when it comes to China.” Though, one participant warned that “we can continue to sell stuff in China, but only as long as the Chinese need us. Once they are able to build things by themselves, they will do so for sure. International corporations might continue to be active there, though under much tougher restrictions than today. That’s why despite Trump and growing populism, there’s no world where Germany and the EU should not be embedded in the Western system.” Given the rise of highly asymmetric network structures that centralize power in key nodes, one of the most interesting discussion points was the concept of “weaponized interdependence” in which global economic networks shape state coercion and gather valuable information, while potentially denying network access to adversaries.

By focusing on the ‘people’ factor in all of this, some suggested that the current unpredictability in the global system is not necessarily coming from China, but more from the United States, given the highly erratic Trump administration. “At this point, it is completely unclear what follows Pax Americana, especially since providing global security is a very costly endeavor.” For Europe, a continent that has benefited from the liberal international order like no other, the current trajectory could not be more concerning — “the Genie, however, is out of the bottle now,” as one participant suggested, and decision makers are under pressure to prepare for a new world in the digital age. “The Chinese want to be seen as an equal, and the US, initially, might have planned to see them as such.” But both countries didn’t seem to be ready for geopolitical rearrangements of that magnitude, and one can only hope that the new bipolarity doesn’t descend into chaos.

The meeting in Berlin was part of the Atlantic Council’s ongoing endeavor to establish forums, enable discussions about opportunities and challenges of modern technologies, and evaluate their implications for societies as well as international relations — efforts that are championed by the newly established GeoTech Center. Prior to its formation and to help lay the groundwork for the launch of the Center in March 2020, the Atlantic Council’s Foresight, Strategy, and Risks Initiative was awarded a Rockefeller Foundation grant to evaluate China’s role as a global citizen and the country’s use of AI as a development tool. The work that the grant commissioned the Atlantic Council to do focused on data and AI efforts by China around the world, included the publication of reports, and the organization of conferences in Europe, China, Africa, and India. At these gatherings, international participants evaluate how AI and the collection of data will influence their societies, and how countries can successfully collaborate on emerging technologies, while putting a special emphasis on the People’s Republic in an ever-changing world. Meetings in Africa and India are scheduled to take place later this year and summaries of the roundtables in Paris, Brussels, Beijing, and Shanghai have been published.