by Josh Lipsky

Changing the narrative

Once upon a time, the dominant narrative about China’s rise went something like this: What used to be a country stuck in a state-run economic morass had, thanks to its embrace of open-market reforms, broken out from the pack—putting it on track to eventually converge with the world’s largest economies. China might become a geopolitical challenger of the United States and its allies, the narrative went, but commercially both powers would increasingly play the same game. The story we in the capitalist world told ourselves was perhaps even comforting: On the economic front, at least, what China really wanted was to be more like us.

But then China seemingly changed course. In recent years, an increasingly powerful Xi Jinping reasserted the role of the state in the economy. Beijing’s new direction was no longer so clear—or comforting. Amid this uncertainty, a counternarrative was born: China’s purported economic liberalization had been an illusion all along, designed to get a naive United States to give Beijing a free pass as it gathered strength to become a superpower.

Both of these narratives are wrong. With China, the story is never so simple. The truth is that China still hasn’t decided which direction its economy is ultimately headed. And we need a credible way to track its trajectory.

Seeking clarity on China’s economic course, the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center, which I direct, joined with the China experts at Rhodium Group to launch an innovative, data-driven investigation. What we found tells a nuanced and often surprising story about China and its economic model—a primary source of tension between Beijing and the rest of the world.

Here’s the key takeaway: China is, in fact, conflicted—slowly opening up its economy in some areas while swiftly retrenching in others. In key sectors, Chinese leaders are backtracking. In others, they simply can’t figure out how to successfully reform. And while this zigzag worked in the 2010s, it could become a self-inflicted wound in the 2020s. That’s because China’s economy is now on shaky ground. Its growth over the last decade was largely built on credit-fueled spending that the country can’t afford to replicate in the decade ahead. This means officials in Beijing will need to get serious about the liberalizing reforms they’ve been promising since China’s accession to the World Trade Organization twenty years ago. Otherwise they may face a severe economic slowdown, which would upend the march to prosperity that has been so central to the Chinese Communist Party’s success.

China is, in fact, conflicted—slowly opening up its economy in some areas while swiftly retrenching in others.

Our project started with a foundational question: Is China’s economy becoming more or less like those of the United States and other open-market countries? The answer couldn’t be more important. Mutual trust between the two powers has eroded dramatically—with the United States convinced that it has been taken advantage of through unfair Chinese economic practices, and China insisting that it is in fact reforming and just needs more time to do so like any developing nation.

If China is converging with open-market systems, it would mean that its leaders still see benefit in economic liberalization. Policymakers in the United States and other open-market economies could assume Xi will eventually be compelled—by his desire for continued growth—to make more concessions to international norms such as reducing industrial subsidies and opening up to foreign capital. The United States could slowly reduce tariffs and step away from the mutually destructive trade wars that began in 2018. US and European businesses could count on predictability and continue to invest in China with confidence.

But if China is diverging from open-market systems, it would signal that Beijing believes the country can sustain sufficient growth even as the government clamps down on its private market. Policymakers in the West would then be justified in reassessing the way their countries engage with China and thinking more strategically about protecting their own supply chains and companies (even if those companies haven’t yet fully realized the risk).

To find the answer, we’re launching the inaugural report of our China Pathfinder Project—an exploration of China’s economy in six areas that economists consider critical for open markets. We used this data to create a new scoring system that compares both China’s record of liberalization and its economic performance with those of the United States and nine other leading open-market economies. We then tracked how China has progressed on these metrics over the last decade.

The story is there in the data: China has actually moved closer to the world’s open-market economies since 2010, making progress in all six economic dimensions in our study. At the same time, the pace of change isn’t nearly fast enough. China is in last place in all but one category. If we went back in time and presented this study in 2001, when China was preparing to join the World Trade Organization, its membership would likely have been blocked. In key areas, such as foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio investment (for example, the ability for Chinese investors to put their money in foreign stocks and bonds), China is moving so slowly that it is at risk of backsliding.

As Daniel Rosen of Rhodium Group, one of the report’s lead authors, has argued, the truth is that Chinese leaders have tried to make reforms. They’ve just done so in fits and starts, experimenting with measures such as giving companies more autonomy only to reverse course and tighten the reins when they didn’t like the results. Time and again, fear of potential economic volatility won out over the promise of liberalization and growth. Indeed, this dynamic is playing out right now with Beijing’s crackdowns on the big tech companies that have helped fuel so much of the country’s economic progress. But China still hasn’t paid a painful economic price for that tradeoff—yet.

These failures to reform are hurting China more than its leaders might realize. As we assessed the results from the study, we were struck not by how much China has grown in the last decade, but rather by how marginal its growth has been compared to its size and potential. In other words, China has been leaving a lot of money on the table. That may no longer be viable; the People’s Bank of China has estimated that if the economy were to experience “severe stress”—something that could result from further COVID-19 lockdowns or aftershocks from the potential burst of its property bubble—growth could slow to as little as 2 percent by 2023.

That is not sustainable in a country accustomed to more than 6 percent GDP growth over the last decade. While advanced economies like the United States and United Kingdom routinely experience growth around 2 percent, such a scenario in China could lead to mass layoffs, a rapid tightening of credit, and, perhaps most troubling for Xi, a serious blow to his authority.

The study reveals a number of additional ways that the conventional wisdom often gets the Chinese economy wrong. We tend to think of China as a titan in the realm of foreign direct investment—both incoming and outgoing. But the data comparing each country’s outward FDI stock (i.e. total accumulated value) to the size of its economy shows that China is lagging behind countries such as South Korea and Italy.

Or take the inclination in Washington, DC to overestimate the reach of China’s currency, the renminbi (RMB). Much has been written about how the RMB might even rival the US dollar one day. That’s an impression bolstered by the RMB’s 2016 inclusion in the International Monetary Fund’s vaunted Special Drawing Rights basket, which is essentially a stamp of approval that a currency is truly “global.” But the actual data shows that international use of the RMB has flatlined.

The RMB is the currency of choice in less than 3 percent of all cross-border transactions, with no signs of an uptick in the future. The reality is that without the Chinese government implementing reforms to capital controls, the RMB will remain a regional currency at best.

On the other hand, the study shows that there are areas where China’s economy is actually more competitive than we often think. The highest market concentration of enterprises—meaning only one or two companies in a particular industry—is not in China but in Canada. China and Italy are roughly tied on the measure of trade openness, and South Korea ranks last. In 2020, in fact, China had a lower average tariff rate than the United States did, thanks to Beijing dropping barriers on other countries even as it raised them on the US. Meanwhile, China’s innovation sector is not in terrible shape, with venture-capital investment as a share of GDP outpacing nearly every other country except the United States and the United Kingdom.

The China story, in other words, is more complicated than either the Chinese—or Americans—like to admit.

* * *

This is exactly the sort of complex picture of China’s economy that policymakers need to see but currently lack. One of the main causes of this knowledge deficit is that governments have often been operating with obsolete data on China—they’re gazing at the stars without recognizing that they are looking at light from years ago. Too comfortable in their prior assumptions, policymakers have failed to adapt to the rapid transformations happening in the country.

We can’t even answer basic questions: What is China’s economic model? Is China becoming more or less like open-market economies? Or some combination of both?

The upshot is that the decisions being made in the halls of power around the world are based on a lack of understanding about the economic forces driving China’s ascendance and its new assertiveness in domains ranging from military to technology. We can’t even answer basic questions: What is China’s economic model? Is China becoming more or less like open-market economies? Or some combination of both? And how are the United States and its allies stacking up against China across the various dimensions of their economic competition? In short, what’s the score?

Keeping score

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Too often, the idea of assessing China’s economy is dismissed as impossible because Beijing keeps the relevant data opaque and even manipulates it. But our teams have shown that it is possible to uncover objective data about the Chinese economy and ground analysis in the facts. We can set benchmarks, and we can use them to measure China’s movement toward or away from open-market norms—not just today, but in the coming months and years. We’ve created a new way of looking at China’s economy, the China Pathfinder data-visualization hub, to do exactly that. We’ll be updating it every quarter with analysis of the most recent trends and refreshing the entire project annually.

This common language to measure and make sense of China’s economy doesn’t just benefit the United States. It benefits US allies in Europe and the Pacific. And it benefits China, too. Right now, there is no ground for mutual understanding between Beijing and Washington and its allies. Our goal with this project is to help establish that common ground, at least when it comes to economics.

The study, compiled over the past eight months, focused on six key economic domains: a sophisticated financial system, a competitive market, the ability to innovate, openness to trade, and openness to foreign companies investing from overseas in both the real economy and markets.

Governments have often been operating with obsolete data on China—they’re gazing at the stars without recognizing that they are looking at light from years ago.

Our data compares the China of 2010 with the China of 2020, and then compares that recent version of China with the world’s ten largest open-market economies. We created composite scores in each area on a scale of 0-10 (0 being the least open, 10 being the most open). In tracking China’s progress, the study is only comparing the years 2010 and 2020. It does not incorporate, for example, how more recent shifts like Xi’s tech crackdown have altered China’s trajectory. Those are the kind of changes that will be factored into the analysis as we update China Pathfinder and track China’s progress—or lack thereof—over time.

With that in mind, let’s get to the scorecards.

Scorecard 1

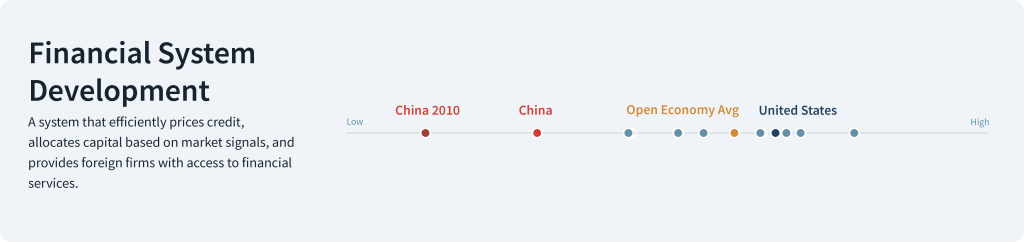

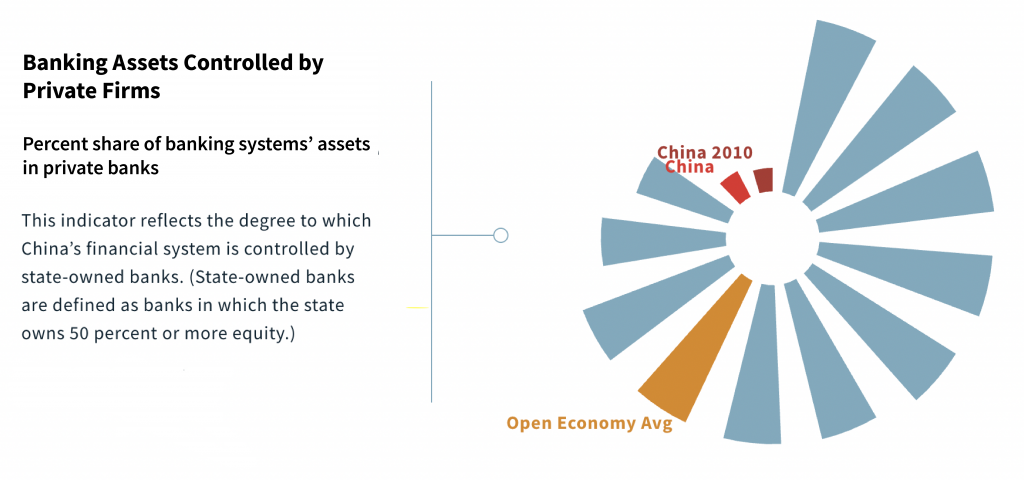

In open-market economies, a modern financial system allows for the efficient pricing of risk and allocation of capital. That may seem technical, but societies run on the ability to gain credit easily and at a fair and predictable rate. Think about a small business getting a loan with a reasonable interest rate so it can expand or a consumer shopping for credit among different banks—or governments refraining from overly intervening in these markets and manipulating outcomes.

Here, based on our scoring system, China clocks in at 2.6 out of 10, compared with an average of 5.8 among our sample of the ten largest open-market economies. That is a step forward from a score of 0.85 in 2010 and reflects progress toward more options—in banking, for example—in China’s financial system. China has been somewhat successful in forcing local governments and corporations to reduce their debt load, but the latest news about the country’s debt-burdened property market shows the fault lines that China’s state-dominated financial system has created. Today China remains a major outlier with nearly 70 percent of banking assets under management by state-related financial entities. The average of the economies we studied is just 9 percent.

Scorecard 2

Market competition is what it sounds like: Firms face low entry and exit barriers, consumer interests are prioritized, and government participation in the marketplace is limited and governed by clear competitive principles. People don’t typically associate China with an “open” or “free market” economy where any business can compete. The data tells us that this is still true, but also that the story is changing. The transformation began in 1978 as a fully state-run economy gradually evolved into what is now a hybrid model.

China scored a 2.97 here in 2020, relative to an open-economy average of 7.82. While this shows that China is lagging considerably, the country actually has progressed from its 2010 score. It’s a mixed bag: In some industries, China has a high level of competition—including from foreign companies. (Think of the American company Tesla, which has been allowed to build the first fully foreign-owned auto factory in China and is now posting strong sales in the country.) Yet China’s state-owned enterprises now account for a higher share of China’s GDP than in 2010, and the Chinese government's promises to make them less harmful to other market participants have not materialized. Market competition is a microcosm of a story we see repeated in different parts of China’s economy: one step forward, two steps back.

Scorecard 3

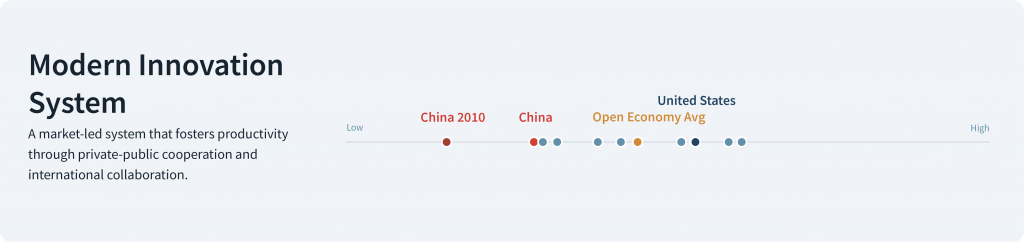

Any healthy economy relies on innovation to drive competition, increase productivity, and create wealth. Innovation systems vary across countries, but they share some general characteristics in open markets: They rely on government funding for basic research but emphasize private-sector investment; they encourage the commercial application of knowledge through the strong protection of intellectual-property rights; and they encourage collaboration with and participation by foreign firms and researchers, except in defense-relevant technologies.

China is more innovative than you might think. In fact, venture capital as a percentage of its GDP has jumped significantly over the past decade. China now trails only the United States and United Kingdom in this department, in part thanks to a vibrant technology startup sector that has created huge returns for investors. China’s deficit in other areas of innovation, however, drags down its overall score considerably. It scored a 2.4 in this category in 2020, compared to an open-economy average of 4.4. While that represents progress from 2010, China still suffers from substantial institutional shortcomings ranging from heavy state intervention to poor intellectual-property protections to the exclusion of foreign companies from large swathes of the creative economy. These results amount to a major dose of reality for China, which aims to be an exporter, not just an importer, of innovation.

Scorecard 4

Free trade is a key feature of open-market economies. It forms the basis of their ability to grow, specialize in areas where they excel, and deliver goods and services to citizens at low costs. But free trade is not always free, as the last few years have reminded us. Countries are moving to protect their own industries and impose tariffs on foreign competitors in a world where there is more focus on the costs of globalization. In our study, we define trade openness as the cross-border flow of goods free from heavy government influence.

Here, China is surprisingly catching up with the pack. Consider tariffs: With a tariff rate of 7.45 percent, China is just above the open-economy average of 6.97 percent. Tariff rates, it’s worth noting, can be volatile due to geopolitical clashes; the average US tariff rate more than doubled to 10 percent between 2018 and 2020, due primarily to the ongoing trade war with China. Meanwhile, China’s tariff rates with countries other than the United States have fallen.

In addition to tariffs, we looked at other ways that countries restrict trade in goods and services and created a trade openness index. China scored a 4.3 on the index in 2020, compared with an open-economy average of 5.6—a substantial improvement relative to China’s score of 3 in 2010 and its best overall score in all six clusters.

It’s findings like these that China might want to highlight as it seeks to portray itself as moving close enough to an open-market economy to meet the requirements for joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, the free-trade agreement that the United States left but eleven other nations have embraced.

The bottom line? China has reduced tariffs to a level comparable with its open-market rivals and has become the world’s largest trading nation in goods. However, restrictions on the services trade—and especially digital services—remain higher than in open-market economies. And China’s relatively strong score comes with an asterisk, since it is known to erect non-tariff barriers such as subjecting foreign companies to burdensome administrative licensing requirements.

Scorecard 5

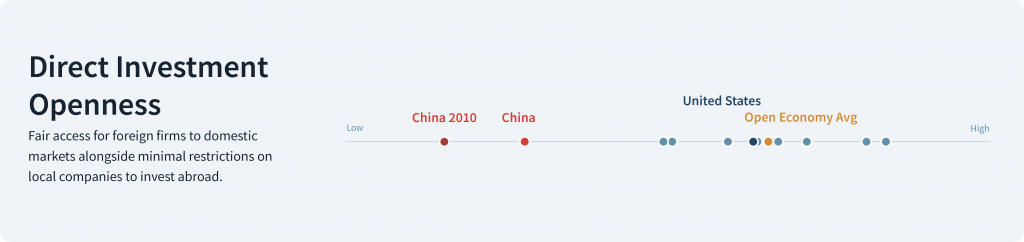

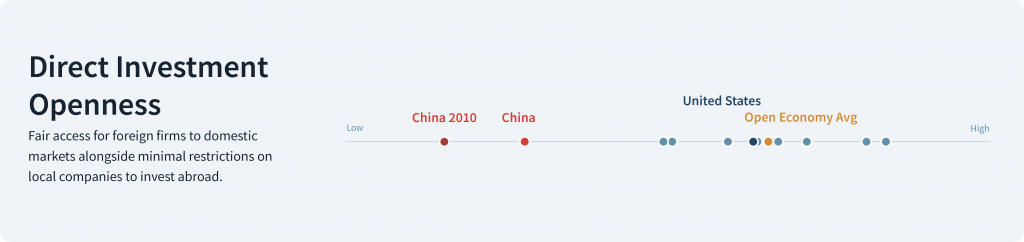

Direct investment openness refers to access for foreign firms to invest in domestic businesses, and freedom for local companies to invest abroad. These are key features of open economies and encourage competitive international markets.

China landed at 2.24 on this measure in 2020, relative to an average of 6.94 within our sample. It’s an improvement from a decade ago. But if you look at inward FDI intensity—meaning the total value of foreign investment as a percentage of its GDP—China is actually regressing. That’s a shocking result. It should be a golden age in this regard for China, which aims to become one of the largest FDI recipients in the world. Over the last several years, however, the Chinese government has slowed the pace of liberalization and failed to create a level playing field for foreign companies. It has also continued to tightly control outbound FDI by Chinese companies, after a short episode of liberalism from 2014 to 2016. Our data shows how much China is hampered by its own restrictions. Despite a surge in mergers and acquisitions (M&A), the share of foreign buyers in Chinese M&A deals has declined over the past decade as persistent government restrictions on foreign ownership and high political risk have curbed foreign appetite for investment.

Scorecard 6

Portfolio investment openness involves limited state controls on cross-border flows, both incoming and outgoing, in equities (i.e. stocks), debt (i.e. bonds), and other financial instruments. It’s a key component of financial-market efficiency. In the United States, most mutual funds or pensions will aim to have about a quarter of their investments in overseas companies—reflecting the old investing adage that you don’t put all your eggs in one basket. The ability to have a diversified portfolio is something we can take for granted in the United States. Not so in China.

The study discredits the narrative that Chinese leaders have cracked the code coveted by so many authoritarians to have a dynamic economy and illiberal political controls all at once.

Over the past several years, foreign investors have flocked to Chinese markets in search of the higher returns that usually outpace the near-zero yields offered in Western bond markets. Nevertheless, China scored a 1.1 on this metric in 2020, compared with 7.86 for our open-market sample. It has barely progressed on this measure over the last decade. But that's not necessarily for lack of trying. Arguably no area of the Chinese economy has seen more attempts at liberalization than portfolio investment, including the creation of new systems to enable foreigners to invest in Chinese markets.

Coming into 2021, the dominant message out of China was that it intended to deepen its integration with the global financial system. But fear of volatility seems to have once again won the day, at least for now. Recently the Chinese government rolled out a series of ostensibly security- and data privacy-oriented restrictions on incoming and outgoing investment. Don’t underestimate the impact of these restrictions. If China were to open up cross-border investment, it could inject tens of trillions of dollars into the global economy—perhaps over $20 trillion cumulatively between now and 2030, according to one estimate from our teams, or roughly a quarter of the value of the global economy in 2021. That’s not going to happen. But the numbers show the potential not just for China but for the rest of the world if Beijing were to finally undertake the reforms it has been promising.

The big picture

This study confounds the narrative that China has never wanted to play by international economic rules. The data demonstrates that under Xi, China has tried to implement some liberalizing reforms. Much of its post-2010 convergence with open-market economies, after all, was under his direction. But, in large part because Xi and other Chinese leaders have been unable to reconcile those efforts with their desire for more control, the reforms have failed to deliver.

That’s a significant distinction. If you’re a US strategist dealing with a Chinese economy that is on its way to becoming more interoperable with your own economy, you’ll play your cards differently than if you believe that Beijing is truly trying to move away from your economic model. For years, policymakers in Washington assumed that Chinese leaders wanted their economy to be more like America’s. Then many of those same people decided that China never wanted to emulate open-market economies at all. US policies have swung like a pendulum because of these assumptions, but both miss the mark.

For US policymakers, the key message from the study is this: China shouldn’t be treated as if it’s attempting to completely diverge from the international economic system. Chinese leaders might yet decide that liberalization is the answer after all. An effort to decouple the US and Chinese economies would thus be not only an implausible and costly economic strategy, but one that treats China like something it isn’t. Washington—and Wall Street—should instead respond to the China that actually exists and focus on areas where there’s real potential to make a difference. If you want to address an emerging problem rather than an old one, place less scrutiny on trade and more on China’s restrictive financial system and Chinese companies that are seeking to list on US exchanges.

The study also discredits the narrative that Chinese leaders have cracked the code coveted by so many authoritarians—that they have figured out a way to have a dynamic economy and illiberal political controls all at once. In category after category, China is inflicting costs on itself through its decisions to not be more like open-market economies. China’s own projections for its GDP growth in 2022 and beyond underscore the risk of this approach. Beijing has reached the limits of what it can achieve with the strategy it’s been pursuing for the past twenty years of attempting to have it both ways.

That means the 2020s could take the country in dramatically different directions. Pathfinder is designed to track the journey ahead. China could either jump to the middle of our dashboard and deliver strong economic growth, or stay mired in its current system and stagnate. Despite what you read about Xi and his intentions, neither outcome is predestined.

Josh Lipsky is the director of the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.

This story draws from the new report “China Pathfinder: Annual Scorecard,” produced by Rhodium Group’s China team in collaboration with the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center. The principal contributors to the report on Rhodium’s team were Daniel H. Rosen, Thilo Hanemann, Rachel Lietzow, and Ryan Featherston. The principal contributors from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center were Josh Lipsky and Niels Graham. Check out the full report and our exclusive interactive database on China’s economy at http://chinapathfinder.org/