Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), chairwoman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resource Committee, and Senator Mark Warner (D-VA), co-chaired the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center’s US Energy Boom and National Security task force, which convened foreign policy, defense, and energy experts. The experts assessed how the United States can strengthen American leadership, advance international security, and promote global prosperity by leveraging necessary hydrocarbon export policies and deploying US prowess in energy innovation and technology to others.

The task force report, Empowering America: How energy abundance can strengthen US global leadership, makes the case for a more robust energy strategy that capitalizes on US energy resources to advance our foreign policy and economic interests. It calls on US policymakers to repeal the crude oil export ban, ease the process of licensing for LNG exports, sustain research and investment in clean energy technology, support energy diplomacy and technical assistance abroad, advance North American energy integration efforts, and more. The report unequivocally concludes that, if properly utilized, American energy abundance will be an extremely valuable tool that favorably impacts global energy security, trade, and US foreign policy.

Table of contents

Energy and national security: regional perspective

Economic and market benefits of the US energy boom

Executive summary

For decades, America’s prosperity and security have been grounded in a strong economy, preeminent military power, promotion of open, rules-based trading systems, and networks of regional security and economic cooperation. Today, American leadership is challenged by an arc of instability from Pakistan to the Persian Gulf and Africa, a belligerent Russia, an increasingly aggressive China, and political polarization at home. Given the breadth and scope of the threats our nation faces, we must make critical choices: how to deepen commercial and security ties with partners in the Pacific and Atlantic, how to combat terrorist threats in the heart of the world’s global energy reserves, and how to promote the rule of law and international order.

We are fortunate at this moment to have access to a new source of American power and leadership that can help us surmount these challenges—our energy abundance. Thanks to a uniquely American blend of innovation and entrepreneurship, the United States has become the world’s largest oil and natural gas producer, with exportable surpluses of natural gas, light oil, and petroleum products. We managed to reduce our own greenhouse gas emissions from power generation largely through market forces.

The choice we face today is whether we will embrace this remarkable resource to enhance our global leadership, in tandem with our traditional diplomatic, development, and security tools. Led by Senators Lisa Murkowski and Mark Warner, our task force of foreign policy, defense, and energy security experts unequivocally believe that we should.

The importance of growing and sustaining a powerful energy production base is essential. Today, we enjoy more self-sufficiency in energy than we could have imagined in the 1970s. Along with Canada and Mexico, we have achieved continental self-sufficiency, reducing the risk of a physical disruption of supply from the Middle East. Relinquishing this achievement, by failing to encourage the US productive base, would be illogical and irresponsible.

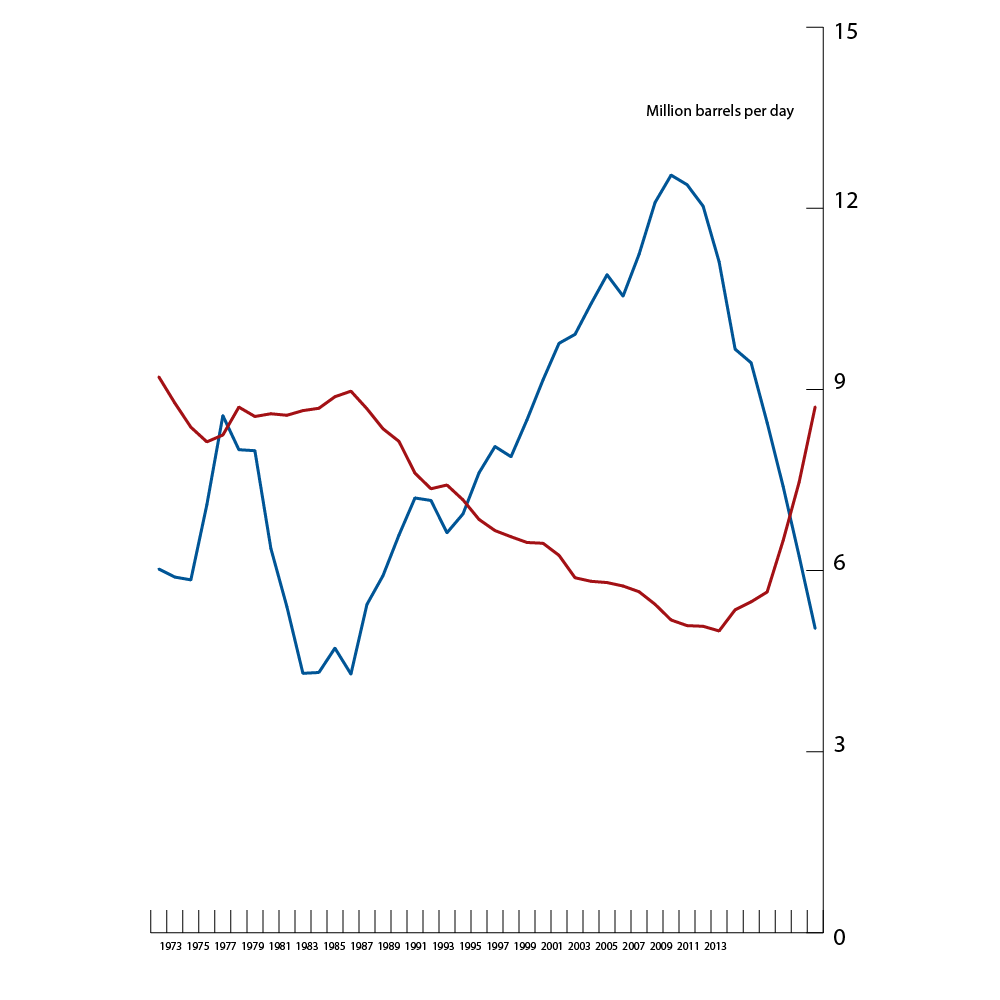

Our energy abundance impacts global energy security as well as domestic security. Our resource base gives us the ability to make energy markets more competitive and transparent, and to reduce the impact of oil and natural gas supply disruptions from abroad. Our natural gas production has created a global surplus of liquefied natural gas (LNG). This surplus brought down energy prices in Europe and Asia, forced Russia to reduce its monopoly pricing in Europe, and eroded historical linkages of natural gas prices to oil prices in Russian gas contracts in Europe and for spot contracts in Asia. Our unprecedented rise in oil production, from 5 million barrels per day (b/d) to a 40-year high of 9.5 million b/d in only 7 years,1US Energy Information Administration, Short Term Energy Outlook (July 2015), http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/steo/report/us_oil.cfm. The 9.5 million b/d is EIA’s projection for US crude oil production in 2015. helped to prevent a price spike from being triggered by the Libyan revolution, to sustain Iran oil sanctions, and to mitigate the market effects of a series of unplanned oil disruptions across the globe.

We are fortunate at this moment to have access to a new source of American power and leadership that can help us surmount these challenges—our energy abundance.

America now must practice the philosophy we have preached at home and abroad since 1973: join the global market and reject protectionism. The United States has many tools with which we can help other nations gain autonomy, prosperity, and energy security, but allowing unfettered exports of our natural gas and oil abundance would be a force multiplier with powerful results.

Many of the foreign policy challenges our nation faces today have a strong energy component—full US participation in energy markets can play a critical and positive role in helping to address these issues. Europe seeks to diversify oil and gas supplies away from Russia. Asian consumers will account for most energy demand growth for decades to come but seek to diversify their supplies of oil and gas to ease their current dependence on the Middle East. Latin America and the Caribbean, faced with declining credit from Venezuela, seek cost-competitive sources of energy supply. The African continent, India, and many nations elsewhere seek natural gas as a more available and affordable source of feedstock for power generation.

Energy supply, and indeed hydrocarbon supply, is only one pillar of the US energy security architecture. As our report details, we will need to encourage competitive markets, multiple pipelines in Europe, and cost effective systems of integrating renewables to enhance European energy security. Price reform, distributed power, and better investment frameworks will be essential to expand both Africa’s and South Asia’s access to energy. Renewable energy, nuclear power, and more efficient coal combustion systems will also be essential to Asian energy security. US leadership in diplomacy, innovation, development assistance, and support to other areas will be indispensable for fostering both energy security and a sure path to a lower-carbon global economy.

But we must be clear eyed about the continuing salience of oil and gas supply in international security today and (in nearly every energy outlook) through 2040. While the world today faces a seeming oversupply of crude oil, with prices that dropped dramatically in less than a year, it is naïve to assume that this situation is permanent. More than half of the world’s oil reserves lie in the Middle East and North Africa, with approximately 17 million barrels per day of oil and 30 percent of the world’s LNG traffic traversing the Strait of Hormuz.2BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2015. With Syria, Yemen, Iraq, and Libya immersed in civil war, with an Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) presence in Iraq, Libya, and Yemen, persistent threats to Saudi Arabia’s government from al-Qaeda and ISIS, and a potential competition for regional hegemony between Iran and Saudi Arabia, it would be negligent not to plan for significant oil supply disruptions.

America’s energy abundance cannot solve every nation’s energy insecurity, or replace all disrupted supply from the Middle East. But we can engage in an unprecedented level of support and self-help. We can give other nations a choice in where they buy their oil and gas. With modest exports, or even with the mere prospects of exports, we can make energy markets more competitive and diminish the market power of those who seek to earn monopoly rents. We can lower global energy prices by increasing global supply. We can accelerate the transition to a lower carbon global economy by facilitating a more global market for LNG and leveraging American next-generation energy technologies. US oil production is unlikely to continue to increase indefinitely and withdrawing from the world market now may be very costly later.

While we cannot be the world’s market balancer like Saudi Arabia has been, with spare capacity in the ground to bring to market in thirty days, we can be the world’s surge producer. American shale oil and gas can come to market in months, faster than deep water or other forms of oil and gas production that can take years. All we need to do is to allow the price signals of global energy demand to reach the American entrepreneurs who can deliver surge supply. This requires removal of export constraints designed for another time and another market.3See footnote 42.

This task force report details the nature of our abundance, the importance of deploying our prowess in energy innovation and technology to others, and the ways in which we can pursue our responsibilities as a global leader on energy and the environment, while leveraging our supply abundance at the same time. America must embrace this new tool of power and leadership, not shrink from it. This embrace will support our global leadership in trade and security, and signal an outstretched helping hand to Europe and Asia that they clearly seek. To ignore this opportunity would be a signal of withdrawal and retreat when the need for greater leadership is acute. We hope this report will be a roadmap for a powerful path forward.

Organization of the report

This report describes the nature of the new US energy endowment, US energy security interests, the linkages between US energy and security interests in key regional areas, the key findings of the task force, and our recommendations.

Key recommendations

- Lift the ban on crude oil exports, while retaining presidential authority to add restrictions when in the national interest.

- Further lift export restrictions on LNG, while preserving the environmental and safety review process.

- Conclude the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations without restrictions on access to US energy exports.

- Support energy diplomacy and technical assistance.

- Combat global energy poverty by encouraging the development of affordable and reliable energy systems that include both traditional and renewable sources.

- Sustain research and investment into energy storage, renewables, carbon capture and storage (CCS), and other critical technologies.

- Consider ways to expand the collective energy security system to include more producers and consumers, especially China and India—which are developing strategic stocks—and trading partners with insufficient strategic stocks to address a supply disruption.

- Work with Canada and Mexico to use North American energy production and infrastructure to advance common security goals.

- Work with Europe and within NATO to support allies’ energy security.

The US energy endowment

The United States has significant natural resources endowments and technological prowess that can empower US policymakers to help meet US national security and global economic interests.

US oil and gas resources

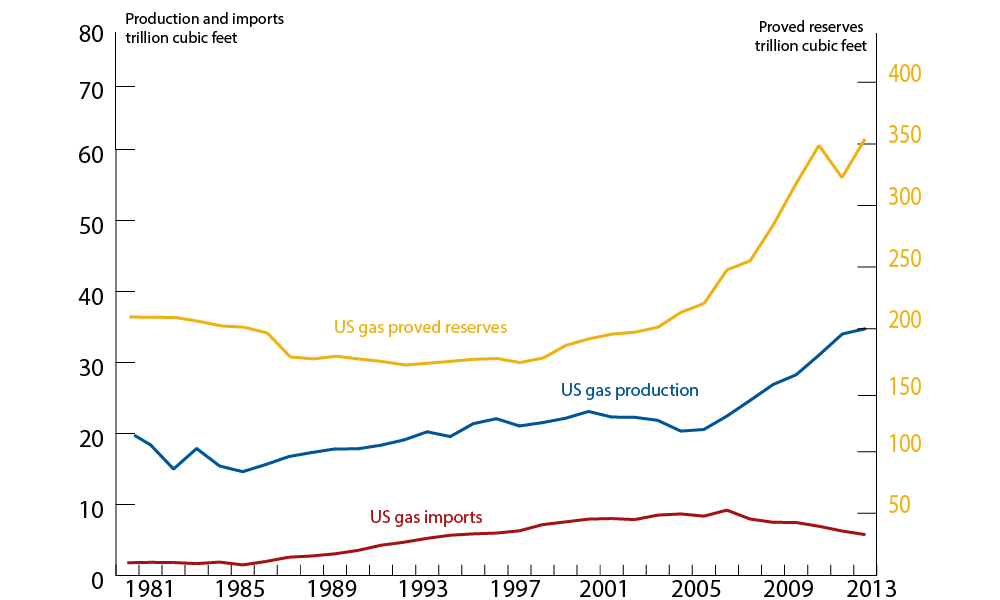

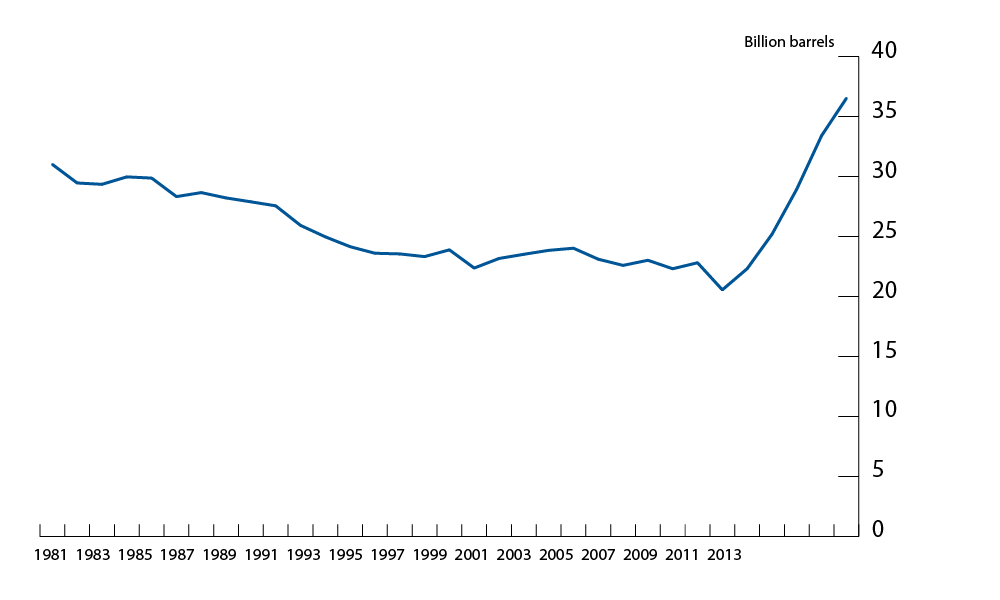

US natural gas and oil reserves are enormous. Proved natural gas reserves grew to 354 trillion cubic feet (tcf) in 2013,4EIA, “US Crude Oil and Natural Gas Proved Reserves,” December 2014. while technically recoverable gas resources were estimated in 2012 to be 2,266 tcf,5EIA, “Oil and Gas Module,” 2014. or more than 80 years of US consumption at current rates. Crude oil and lease condensate reserves increased from 20.5 billion barrels in 2008 to 36.5 in 2013.6EIA, “US Crude Oil and Natural Gas Proved Reserves,” op. cit. This is the result of US-pioneered advances in hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling that have allowed production of hydrocarbon resources from low permeability shale with low cost applications (graphs 1, 2, and 3). These advances were a product of private property and mineral rights ownership, technology advances, open domestic markets, a geological database from more than a century and a half of oil and gas production, a transparent, stable and predictable regulatory environment, and entrepreneurship that has yet to be replicated outside of North America. Both our system and our resources represent unique comparative advantages.7Ed Chow, CSIS, statement to the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, “Importing Energy, Exporting Jobs, Can it be Reversed?,”March 2014.While not the focus of this report, the United States also possesses 19.7 billion short tons of recoverable coal reserves, and 256.7 billion short tons estimated recoverable reserves. The United States produced 984.8 million short tons of coal in 2013, a decline of 187 million short tons since 2008, which supplied 39 percent of US power generation in 2013. The United States exported 118 million short tons of coal in 2013. EIA, Annual Coal Report (April 2015) and EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2015.

The United States experienced an unprecedented rate of growth in crude oil production over the past six years, even as production in many countries stagnated. US production of crude oil and other liquids surged by 5.4 million barrels per day (b/d) as global growth rose by 6.4 million b/d during 2008-14, according to EIA data (graph 4).8EIA International Energy Statistics, July 2015. Includes crude oil, lease condensate, natural gas liquids (NGL), refinery processing gains, and other liquids.

A similar phenomenon took place earlier in natural gas. US natural gas production rose from 18.0 to 25.7 tcf during 2005-14.9EIA, “Natural Gas Summary,” http://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/ng_sum_lsum_dcu_nus_a.htm. The United States began exporting LNG from the Kenai plant in Alaska in 1969. Projects in the lower forty-eight states are coming on-line rapidly, with the US Energy Information Administration projecting that the country will be a net natural gas exporter by 2017.10EIA, Annual Energy Outlook 2015.

New production from this expanded resource base boosted the US economy at a time when other Organization for Cooperation and Development (OECD) economies were stagnating. Energy development directly contributed nearly 1 percent to annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the United States over the last six years and accounted for about 40 percent of overall GDP growth over that period, according to a recent study by consulting company IHS. 11IHS, Unleashing the Supply Chain (March 2015). The US energy boom improved the US trade balance, boosted jobs, personal incomes, and state revenues, and lowered commodity prices.12Charles Ebinger and Heather L. Greenley, “Changing Markets, Economic Opportunities from Lifting the US Ban on Oil Exports,” Brookings Institution,September 2014. According to Moody’s Analytics, oil and gas-related industries created more than 250,000 jobs since 2006, most resulting from the surge in shale oil and gas development. For each of these jobs, an estimated 3.4 additional jobs are created, producing a total of just over 1 million jobs.13Chris Lafakis, Moody’s Analytics, presentation to Atlantic Council Task Force on the Energy Boom and National Security, April 2015.

New production from this expanded resource base boosted the US economy at a time when other Organization for Cooperation andrnDevelopment (OECD) economies were stagnating.

Additionally, growth in domestic oil production and refined products exports improved the US trade balance and helped support the dollar as net oil imports declined. Without the shale oil boom, the $215 billion oil import bill amassed by the United States in 2014 would have been an estimated $360 billion, according to a US investment specialist.14Ibid.

Graph 1. Shale projects have increased US proved natural gas reserves and production, and reversed growth in imports

Graph 2. Shale projects have dramatically increased US proved oil reserves

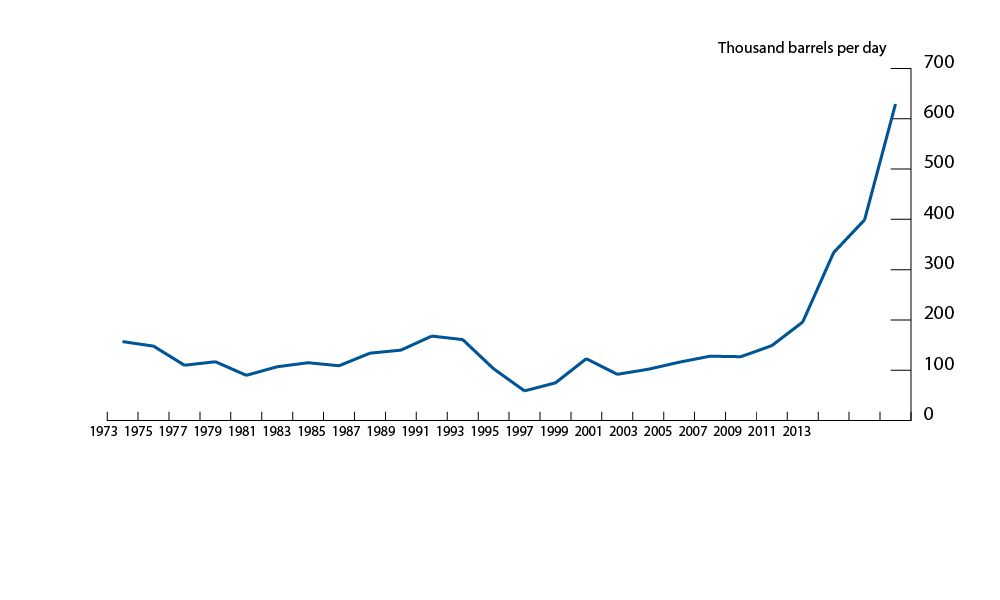

Graph 3. US crude oil production has soared while oil imports have plunged*

*Includes lease condensate, which the EIA defines as light liquid hydrocarbons recovered from lease separators or field facilities at associated and non-associated natural gas wells. Mostly pentanes and heavier hydrocarbons. Normally enters the crude oil stream after production.

The expanded oil and gas resource base also improved US competitiveness by increasing the attractiveness of investment in US energy development and lowering electricity prices. Moody’s Analytics assessed that oil and gas structured investment rose by $41 billion since 2006 while non-oil and gas structured investment fell. Additionally, as the result of the availability of low-cost feedstocks, global companies announced $70 billion in petrochemical investment in the United States by 2020.15Ibid.

Energy, technology and innovation

The United States also possesses a rich capacity for energy innovation, provided both by private sources, such as industry and academia, as well as by government outreach and institutions, including our national laboratories. For example, the development of the hydraulic fracturing technology that made possible today’s oil and gas abundance was the result of research and development (R&D) undertaken and funded by both the US government and by private industry. Similar success stories in the realms of nuclear energy, renewable energy sources, and energy efficiency all exemplify the key role that R&D has had in making US energy capacity what it is today.

Graph 4. US exports of crude oil are rising steeply*

*Includes lease condensate, which the EIA defines as light liquid hydrocarbons recovered from lease separators or field facilities at associated and non-associated natural gas wells. Mostly pentanes and heavier hydrocarbons. Normally enters the crude oil stream after production.

The United States is a leader in numerous technology research areas. Some, such as advanced renewable technologies, carbon capture, and energy storage, are often billed as the technologies of the future. But it is important not to forget the technological prowess that the United States has in more conventional energy resources as well. In spite of the fact that the United States has not built significant new nuclear power generation capacity since the 1970s, US companies remain leaders in nuclear research and development. Similarly, continued advances in natural gas-fueled power generation technologies such as combined cycle gas turbines, high-efficiency power transmission lines, ‘smart’ power grids and meters, and others, have provided significant advances in energy efficiency and cost savings. By sharing these technologies in open and transparent markets, and by working to promote the capabilities of US companies to global consumers, the United States can spread the benefits of our technology prowess to our allies and trading partners abroad and enable them to diversify their sources of power generation and their energy suppliers, and enhance the efficiency of their energy systems.

US energy security interests

US interests in the energy space are long standing and closely integrated with our broader national security and economic goals.16Daniel Yergin, “Energy Security and Markets,” in Jan H. Kalicki and David L. Goldwyn, eds., Energy & Security: Toward a New Foreign Policy Strategy, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2013). “Energy security requires continuing commitment and attention—today and tomorrow. Of course, energy security is hardly a new concern. It has been a recurrent issue for more than a century, ever since oil became critical to transportation.” These interests include maximizing diversity of supply and open energy markets, mitigating the energy insecurity of others through bilateral support and collective action, enabling energy access in the developing world, and, more recently, hardening our energy systems against terrorism and cyberattacks.

The United States has long maintained a strong interest in maximizing open, transparent, and freely flowing energy markets. Following the 1973 Arab oil embargo and the creation of the International Energy Agency (IEA), consuming nations abandoned oil sharing allocations and saw the creation of flexible spot markets and an efficient global trading market as the best defense against cartel power.17Thijs Van de Graaf, “International Energy Agency,” in James Sperling, ed., Handbook of Governance and Security, (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2014), pp. 497-498. Global energy security and economic strength are maximized when the market can move supply to meet demand free of mercantile or political constraints. This principle is as important for the viability of renewable technology as it is for oil and gas. The United States embraces this principle by strongly pressing nations abundant in rare earth elements not to restrict their exports, which could deny accessibility on a global basis.

The United States has a paramount and long-standing security interest in reducing the vulnerability of allies and trading partners to political and economic coercion from dominant energy suppliers. The United States is stronger and more secure when our allies and partners enjoy energy security and a resulting stronger economic vitality. Vice President Joe Biden noted similar themes at the 2014 Atlantic Council Istanbul Energy and Economic Summit and called upon leaders to recognize energy as a tool for cooperation: “As leaders in the formulation of energy policy around the world, it’s within your power to help make energy insecurity in Europe and many other places a thing of the past. That should be one of our goals. We have to keep our eye on the horizon, keep moving past old ways of doing business, keep making energy a tool of cooperation, not a tool of division.”18Vice President Biden speech at Atlantic Council’s Istanbul Energy and Economic Summit, November 22, 2014.

In this vein, the United States has an interest in maintaining a collective energy security system with the IEA and our North American partners. With the rise of the developing world, however, global consumption patterns are changing in fundamental ways; the world looks very different than it did when the IEA was created. It is appropriate to consider how these new consumers may be integrated responsibly into a collective energy security system.

The United States has an equally important national security interest in promoting sustainable energy development in emerging countries whose populations currently lack access to energy and energy services, as we are seeking to do through the Power Africa initiative. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton highlighted that expanded, transparent energy access can enhance education and entrepreneurship, increase incomes, fight corruption, and mitigate political instability.19Hillary Clinton speech at Georgetown University, October 18, 2012, http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/texttrans/2012/10/20121018137692.html#axzz3bRyyEGnQ.

The linkage between US energy and security interests, and the embrace of multiple paths to advance these interests, is both bipartisan and long standing. We can agree that increased availability of US energy supplies on the global market increases price competition, boosts countries’ purchasing power, and strengthens resilience during uncertain times. We can agree that US efforts to develop technologies and share experiences in technological advancements enables other nations better access to domestic energy supplies, including both conventional and renewable sources, and boosts energy efficiency.20National Energy Policy, May 2001, http://prop1.org/thomas/peacefulenergy/cnesM.pdf; Comprehensive National Energy Strategy, April 1998, http://www.wtrg.com/EnergyReport/National-Energy-Policy.pdf. As we survey how these challenges manifest themselves across the globe, the use of a combination of tools is key in every region.

Energy and national security: regional perspectives

Energy plays a salient role in addressing the primary security challenges that US allies and trading partners face. Although these challenges vary in kind and degree, they all contain an essential energy component. The manner in which these challenges are addressed will affect Washington’s ability to muster coalitions to address key national security issues.

Europe

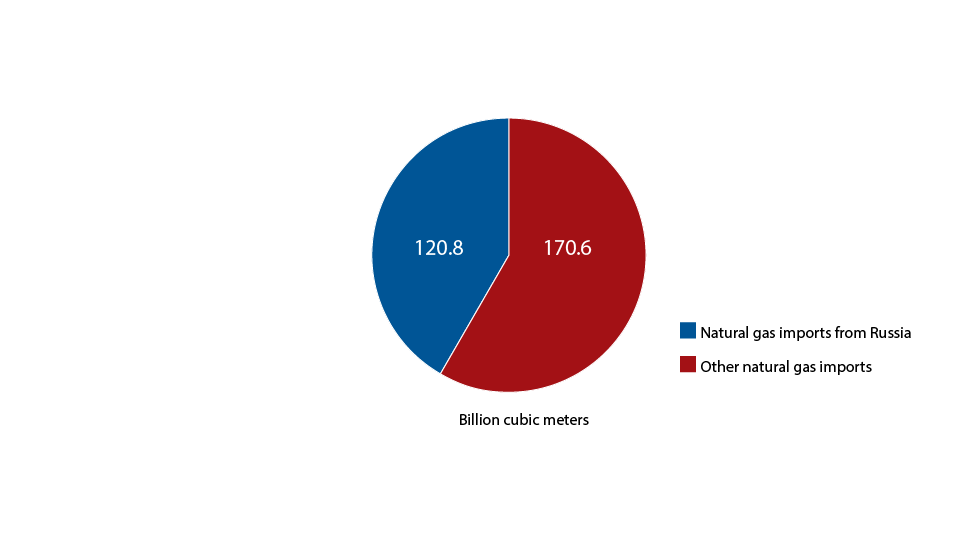

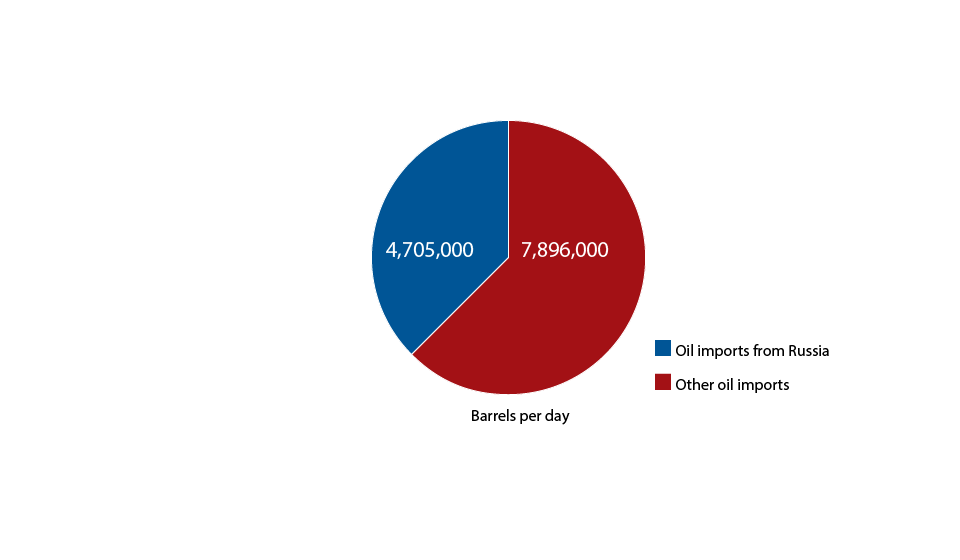

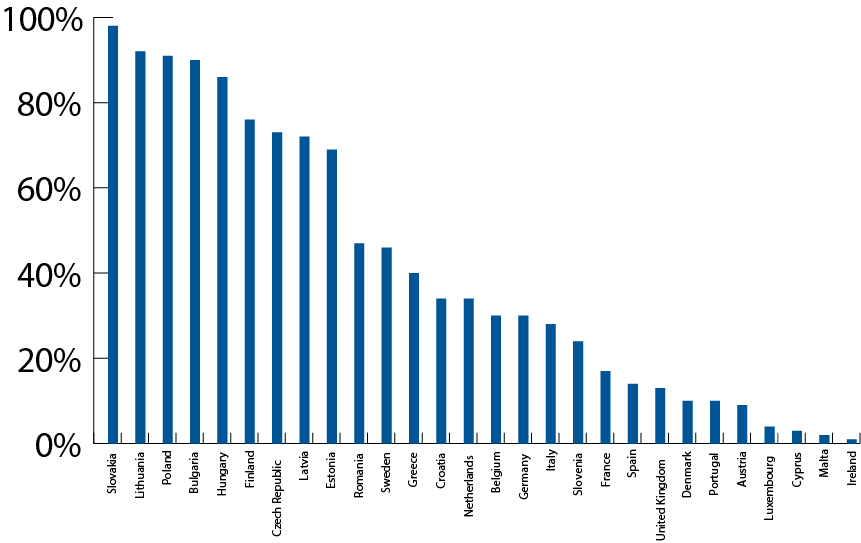

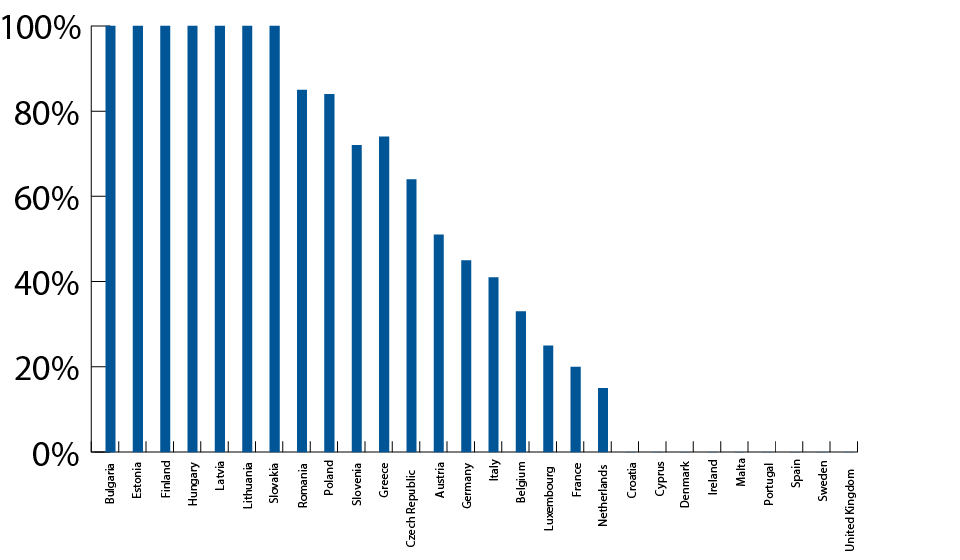

In Europe, the primary security challenge is resisting Russia’s rejection of international law, disrespect for sovereign borders, and use of energy as a tool of coercion. There is a direct connection between some nations’ reliance on Russian energy supplies and their ability to enjoy true autonomy. Ongoing European work toward and Washington’s support for a fully integrated European gas market is critical. However, efforts are challenged by a lack of natural gas supply diversification, pipeline interconnections, and Gazprom’s close ties to many Western European companies. In addition, while the United States has thus far proven successful in working with the European Union (EU) to impose multilateral sanctions on Russia’s financial and energy industries and tie future sanctions relief to Russian implementation of the Minsk agreements, Moscow’s dominant position in the European gas market and—when it chooses to be—the lowest cost supplier may make this success very challenging to sustain (graphs 5, 6, 7, and 8).

While Russia can always be the lowest cost supplier of gas to Europe, the key to US and EU policy has been to make the European market competitive and to allow consumers real choice to alternative supply, as a way of checking Russia’s monopoly power.

Europe’s energy insecurity is rising, not falling. Europe’s declining oil and gas production and growing import dependency are making the continent, especially the Eastern Partnership countries, even more vulnerable to Russian supply disruptions. Russia’s gas pipeline policies, first Nordstream and then South Stream and Turkish Stream, and potential expansion of Nordstream to four pipelines to Germany, all threaten to cut Ukraine and the Baltic states off from existing supply routes.21Atlantic Council and Central Europe Energy Partners, Completing Europe—From the North-South Corridor to Energy, Transportation, and Telecommunications Union (2014), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/reports/completing-europe-from-the-north-south-corridor-to-energy-transportation-and-telecommunications-union. Russia is attempting to assert control in the petroleum product market by acquiring refinery assets in Europe to tie product supply to its crude stream. Russia’s Lukoil has a stake in refineries in Bulgaria, Italy, the Netherlands, and Romania, and Russian state oil firm Rosneft owns 50 percent of Germany’s largest refining company, Ruhr Oel, which owns stakes in four German refineries.22Isabel Gorst, “Rosneft: Still Buying Assets,” beyondbrics (blog), FT.com, April 2013,http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2013/04/16/rosneft-still-buying-assets/.“Russian Strategy to Buy up Europe’s Refineries Exposed,” EurActiv.com,May 23, 2014. http://www.euractiv.com/sections/energy/russian-strategy-buy-europes-refineries-exposed-302329.

While Russia can always be the lowest cost supplier of gas to Europe, the key to US and EU policy has been to make the European market competitive and to allow consumers real choice to alternative supply, as a way of checking Russia’s monopoly power.

The European Commission has been actively pursuing, through its laws and regulations, competition policies that would limit the ability of Russia—or any other single supplier—to dominate the European fuels markets and jeopardize regional security. Yet implementation and enforcement of these policies remains a work in progress.23Atlantic Council Conference on the Global Ramifications of the European Energy Union, April 2015.

Ensuring that Europe has access to diverse and market- priced supplies of oil and gas remains a paramount US security concern. The United States has strong trade and treaty ties to the nations of Europe, and has been engaged with these nations in an attempt to minimize the continent’s energy insecurity for decades. Europe showed how US energy abundance enhances its economic security when increased US crude oil and natural gas production enabled European buyers to renegotiate existing contracts at more competitive prices that reflected lower world natural gas prices.24Richard Morningstar speech, “Re-designing the European Energy Map,”March 2012, http://www.hazliseconomist.com/uploads/speeches/Ivestment_Energy_2012/MORNINGSTAR_ENG.pdf. 25Richard Morningstar speech to Plenary Session of Caspian Oil and Gas Conference, June 2011, http://photos.state.gov/libraries/azerbaijan/366196/Press%20Releases/MorningstarCOG%20speech-ENG.pdf.

Graph 5. Russia is the EU’s largest source of natural gas imports

Graph 6. Russia supplies more than one-third of Europe’s total oil imports*

*Europe includes the EU, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, the Western Balkans, and the European microstates.

The utility of US supply of LNG and oil to help make Europe’s energy markets more competitive is evident in European demands to include gas trade in TTIP and bilateral requests to consider including crude oil trade in those agreements.26Gabriele Steinhauser, “EU Wants U.S. to Lift Ban on Oil Exports,” Wall Street Journal, May 17, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/eu-wants-u-s-to-lift-ban-on-oil-exports-1431885401. In addition, encouraging European countries to enhance conditions for investment in indigenous energy supplies could help complement diversification efforts.

Finally, working within NATO in cooperation and partnership with EU and other partners is particularly important to deal with threats to energy security. Energy factors play a major role in the current crisis in Ukraine and are also used to create political and economic pressures on the Baltic, Central and Eastern European, and Eastern Partnership countries. NATO and the EU share interests in threats to critical infrastructure such as major oil and gas pipelines, cyber security, and potential maritime chokepoints for oil and gas flows such as the Baltic and Turkish Straits, which together handle more than 6 million b/d of oil.27EIA, “World Oil Transit Chokepoints Critical to Global Energy Security,”December 1, 2014. NATO also provides an important vehicle to assist new and potential oil and gas suppliers with energy security planning and expertise. Cooperation in energy security can be deepened through increased strategic planning and action at the NATO-EU level, sharing of intelligence on threats to energy supplies, and coordinated responses to energy supply disruptions. As US energy exports increase, NATO’s role in maritime security is also likely to grow.

Graph 7. Share of EU-28 total energy imports from Russia varies by country

Graph 8. Share of EU-28 total natural gas imports from Russia varies considerably by country

East Asia

US demands for nations to diminish imports or investments in hydrocarbons, without willingness to export our own resources, left few options to ameliorate the economic burden of those demands and hampered US sanctions policy—on Iran, Iraq under Saddam Hussein, and Burma.

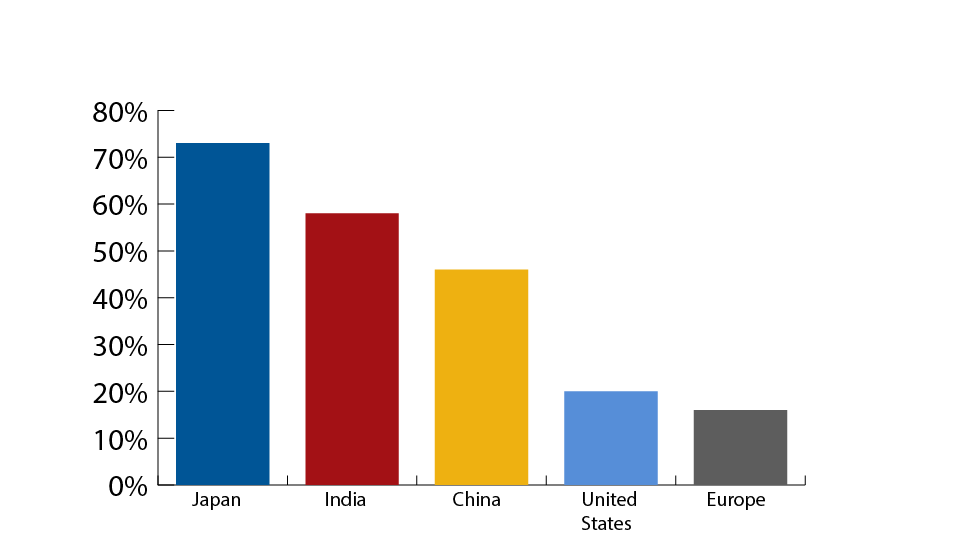

Graph 9. Asian Countries have a higher dependence on oil imports from the Middle East as a share of total imports than other major importers

A lack of indigenous oil supply leaves key regional allies and trading partners increasingly dependent on the Middle East for crude oil and natural gas (graph 9). The absence of strategic stocks in much of the region leaves countries highly vulnerable to supply disruptions and price shocks. South Korea, a US treaty ally and free trade agreement partner, is highly dependent on imported oil and gas supplies. Despite the high cost of energy to these nations’ economies, energy demand continues to grow faster in Asia than in any other region.28The International Energy Agency, in the World Energy Outlook 2014, suggests that China will remain the primary driver of energy growth in the short-run, before growth slows and the primary source of growth shifts to India, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. See http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/media/weowebsite/2014/WEO2014_LondonNovember.pdf. Energy companies in China, South Korea, and Japan have all invested heavily in energy development projects around the world in an attempt to address their lack of, or inability to develop, indigenous resources.

Asia’s desire for energy security—both security and affordability of supply—is unavoidably linked to the efforts of many nations to reduce pollution, better protect the environment, and produce and consume cleaner energy. Many nations in East Asia, particularly China and Japan, are developing renewable resources and utilizing energy efficient technologies. But every one of these systems requires both baseload and backup power to support the share of renewable energy. Today, and in the future, the most cost effective baseload fuel is coal, which is projected to comprise a large share of Asian fuel supply for decades to come. If Asian nations are to add an economic source of baseload fuel to their energy mix, especially where nuclear power is not a viable option, enabling a lower cost supply of natural gas will be essential to carbon reduction and economic growth.

US demands for nations to diminish imports or investments in hydrocarbons, without willingness to export our own resources, left few options to ameliorate the economic burden of those demands and hampered US sanctions policy—on Iran, Iraq under Saddam Hussein, and Burma.

The obvious ways in which the United States can help address these energy insecurities are three fold. First, to the extent that the US energy resource base can increase global energy supplies, provide new alternatives, and reduce costs in the process, exports of crude oil and LNG from the United States can provide a new, reliable, and more affordable source of energy. Increasing global LNG supply, and allowing Asia exposure to Henry Hub priced gas and purchases without destination clauses can further erode the price linkage between oil and gas.

Second, the United States can also promote investment conditions that help Asian countries gain needed technology for unconventional and conventional energy development to increase indigenous supplies and for efficiency improvements that slow demand growth. Where Asian nations have natural resources, such as unconventional resources in China and India, the public and private sectors in the United States can use their combined technological prowess and regulatory expertise to help these nations develop their resources safely and efficiently. These countries should also work to provide the needed incentives for private sector investment. Where nations lack energy access due to inefficient economic frameworks, such as in India and Indonesia, the United States and others can provide technical and regulatory assistance to help modernize these systems in a way that will attract investment and create an enabling environment for clean and other energy investments, including in energy efficiency and subsidy reforms.

Third, the United States can continue to try to integrate major Asian energy consumers, like China and India, into a global emergency management system to minimize market disruptions. Today, neither China nor India are members of the IEA (and have not expressed interest in becoming members), and as such are not directly included in the Coordinated Emergency Response Mechanism (CERM) decision-making structure that coordinates releases of oil from national strategic stocks to stabilize markets in times of supply disruption. Yet both nations are actively developing strategic reserves similar in structure to that of the United States, and as such could be integrated into a global emergency response mechanism to great effect.

Africa/South Asia

In Africa and large parts of South Asia, lack of access to energy services presents acute security and economic challenges. Energy poverty can contribute to internal unrest and opportunities for destabilizing campaigns by groups like al-Shabab in East Africa. Solutions on the supply side include developing indigenous resources, more renewable energy, and adopting modern technologies.

To be effective, the US energy security toolkit for both these regions must prioritize helping these nations to create frameworks that attract international investment and foster governmental and other institutional capacity. For example, integrating renewable energy into existing energy systems while fairly sharing the costs of backup power is a major challenge.29 IEA, Energy for All: Financing Access for the Poor (October 2011), http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/weo2011_energy_for_all.pdf.

Tanzania and Mozambique are examples of where US bilateral and multilateral diplomacy are essential in helping officials to continue to design governance frameworks to manage their world-class natural gas reserves. Support for good governance of the energy sector and, once commercial production begins, effective use of wealth derived from these resources will help promote stability in these countries and may, in the longer-term, provide an example that other emerging producers in the region can follow.

In South Asia, access to global resource markets is essential to development. Access to natural gas, for example, is limited in India, which needs access to low cost LNG to diversify its baseload supply from coal. India also seeks to diversify its oil supply.30India is currently looking as far away as Mexico for oil supply to lessen its dependence on the Middle East.

Africa and South Asia both provide important examples of where US energy diplomacy and policy should be practical and non-ideological. Moving countries in these regions toward economies that use cleaner sources of energy, emit less pollution, and are more protective of the environment may look drastically different from the plans in OECD nations. For countries where large portions of the population still rely on the unhealthy burning of biomass (wood, dung, or charcoal) as their primary source of cooking or heating fuel, a switch to electricity generated from coal or natural gas could be an exponential improvement.

Helping these nations gain access to baseload power in conjunction with renewables and off-grid technology could provide the economic growth engine that will be required to move them further down the carbon chain.

US policy in Africa promotes energy access as a component of economic growth and counterterrorism strategy. The United States has numerous policy tools it can deploy. The scope and funding of these programs should be sustained and, where appropriate and feasible, expanded.31Examples include the US State Department’s Energy Governance and Capacity Initiative (EGCI), the Unconventional Gas Technical Engagement Program (UGTEP), US Power Africa, and US support for the UN Sustainable Energy for All.

Middle East

The threat of price shocks from supply disruptions emanating from the Middle East has long shaped US thinking and planning on energy security. The source of disruption has ranged from the 1973 Arab oil embargo to the Iran-Iraq war, to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, to internal unrest in Iran, Iraq, and Libya, and to US sanctions themselves. As noted earlier there has long been a direct relationship between our partners’ access to alternative energy resources and the US ability to foster support for non-proliferation and other policies through sanctions. US oil and gas production growth, to the extent it lowered the cost of compliance with sanctions, played a key role in mustering the political support for tougher sanctions on Iran that has brought the P5+1 negotiations to an agreement.32The P5+1 group that negotiated with Iran on restrictions to its nuclear program consists of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—plus Germany.

Today, we need to consider the utility of increasing US ability to enhance global oil supply in two major respects: backstopping US policy on Iran and ameliorating future supply shocks from the Middle East.

On Iran policy, the United States needs to be able to help replace lost oil supply if the P5+1 agreement is not successfully implemented.

The need to sustain coalition support will continue if Tehran fails to comply with the deal and sanctions snap back into place. It will be challenging for the United States to convince other countries to once again limit or forgo Iranian crude oil imports if the United States refuses to allow domestic producers to export its own crude to countries that consume Iranian crude.33Elizabeth Rosenberg, CNAS, presentation to Atlantic Council, May 2015.Stephen J. Hadley and Leon E. Panetta, “The Oil-Export Ban Harms National Security,” Wall Street Journal, May 19, 2015.

Moreover it may be in the US interest to moderate the resumption of oil and gas relationships between Iran and East Asia and between Iran and Europe as the strategic focus shifts to the security challenge of Iran’s role in the Middle East and its regional policies. Conceding these trade relationships to Iran prior to real progress on the nuclear and other briefs would be a strategic error. Allowing Iran to market its oil and condensate while denying the same right to our own producers would be unfair.

The second major consideration for US energy policy is the threat of an energy disruption in the Middle East. The bulk of the world’s oil and gas reserves lie in the Middle East. Saudi Arabia, the region’s largest producer, continues to play a dominant role in the global oil market by virtue of accounting for roughly a third of the cartel’s 31 million b/d crude oil production34IEA, Oil Market Report (June 2015). The OPEC crude oil production does not include approximately 6.5 million b/d of natural gas liquids produced by OPEC. and the lion’s share of global spare capacity. Riyadh renounced its role as the market stabilizer in 2014 as it opted instead to compete for market share, particularly in Asia.35Robert McNally, The Rapidan Group, presentation to the Atlantic Council, April 2015.

Saudi Arabia’s political stability is perhaps the most salient variable in the global oil market, and recent leadership changes, shifting demographics, and rising geopolitical competition with Iran create uncertainties and make it an important area to watch. Saudi Arabia is also short of natural gas and uses increasing shares of its oil production for power generation.36EIA, “Saudi Arabia Uses Largest Amount of Crude Oil for Power Generation Since 2010,” Today in Energy, September 2014, http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=18111. However, Saudi Arabia lacks a presently accessible and economic natural gas supply and these shortages could open the door for collaboration with its gas rich competitors Qatar and Iran or, more likely, a move to large-scale renewable energy, likely solar energy, where the United States can be a useful partner.

Iran will be emerging from sanctions if a pact is ratified on nuclear and other issues, and Iraq continues to emerge from war and sanctions. Both seek to vastly increase their oil and gas production to secure necessary revenues for national priorities. Competition has led to a race to the bottom in oil prices that could underprice and crowd out non-OPEC supplies, especially in high cost areas such as Brazil’s pre-salt fields and the Canadian oil sands.

Despite its ample resource endowment, the region continues to be a major source of geopolitical and market instability. It is unclear yet whether the rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran will lead to direct conflict, more proxy wars, or rapprochement. The threat that ISIS poses to Saudi Arabia, or the degree to which it might destabilize the Kingdom’s Eastern Province, is unclear. Supply disruptions or the threat thereof in Iraq, Libya, and Yemen, in addition to the threat of a larger-scale conflict in the Persian Gulf, continue to endanger the stability of global markets and the energy security of the United States and its allies and trading partners worldwide.37Greg Priddy, Eurasia Group, presentation to the Atlantic Council, May 2015.

In order to mitigate these risks, and to deter the threat of a return to the use of oil as a weapon by future Middle East governments, it remains an axiomatic principle of global energy security that the United States should continue to foster non-OPEC supply as a hedge against intentional or unintentional disruptions from the region. European and Asian buyers overtly seek alternatives to hedge against disruptions in Middle East crude supply, which the United States has an abundant supply to export. While the Middle East can always dominate incremental oil production due to low costs of production and transportation, we cannot count on the state-run national oil companies in the Middle East to invest sufficiently to meet rising demand. If we want to hedge against a rising market we would do better to count on our own privately driven production.38Investment by national oil companies can be less responsive than that of private oil companies to higher prices because countries can meet their budget needs more easily without raising production.

Finally, while the United States cannot be the world’s market balancer like Saudi Arabia has been, with spare capacity in the ground and surface facilities to bring to market in thirty days, we can be the world’s surge producer.39Unlike Saudi Arabia, and to a lesser extent the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Kuwait, the United States is not a market balancer because it does not have spare oil production capacity in the ground and in surface facilities that would allow it to increase or decrease production at will. But the shale oil revolution has provided the United States an ability to surge its output because the techniques and supporting equipment and infrastructure used to increase shale oil production can be applied quickly and flows from new wells can be brought on line rapidly. This ability to surge production provides additional flexibility to the US and global markets.We use the EIA’s definition of spare capacity as the volume of production that can be brought on the market within thirty days and sustained for at least ninety days. The IEA recently changed its measure of spare capacity from production that can be brought on the market within thirty days to production that can be brought on the market within ninety days, which matches Saudi Arabia’s approach.

Central/South America and the Caribbean

In Central America and the Caribbean, energy insecurity arises both from dependence on high cost, high carbon fuels and on credit from a single supplier. In South America, economic and energy demand growth is expected to continue over the coming decades. In both Central America and the Caribbean the cost of electricity can reach three or four times that of the level in the United States.40Castalia Strategic Advisors, Natural Gas in the Caribbean—Feasibility Studies, Report to the Inter-American Development Bank (August 2014), p. iii, http://www.iadb.org/Document.cfm?id=39205253. From a diplomatic perspective, dependence on credit financing of diesel and crude oil from Venezuela has long handicapped US efforts at democracy promotion through the Organization of American States (OAS), and stifled the transition of these economies to lower cost and lower carbon fuels.

It is in the national security interest of the United States to support the economic growth of our neighbors, but volatile fuel prices and limited supply could endanger that growth.41Most of Latin America is short of refined products due to strong domestic demand growth and an inability of local refiners to expand refining capacity. These trends are likely to continue, creating a strong market for North American exporters, in turn supporting continued high refinery utilization and refiners’ ability to absorb large volumes of LTO supply.” See Tim Fitzgibbon and Matt Rogers, “Implications of Light Tight Oil Growth for Refiners in North America and Worldwide,” McKinsey & Company, January 2014.

The United States now possesses an opportunity to apply its energy endowment to transition regional influence away from Venezuela and reorient the region toward a more prosperous, sustainable, and environment friendly economic development trajectory.42David L. Goldwyn and Cory R. Gill Uncertain Energy, The Caribbean’s Gamble with Venezuela (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, July 2014), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/images/files/Petrocaribe_RDO_18.pdf.

The United States has three major long-term policy efforts to support the region. The Vice President’s Caribbean Energy Security Initiative (CESI) seeks to create an enabling environment for renewable energy to make Central American and Caribbean economies competitive and provide certainty to investors in the form of more robust regional security of supply.43Vice President Biden’s remarks at the Caribbean Energy Security Initiative, hosted at the Atlantic Council on January 2015, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/01/26/remarks-vice-president-biden-caribbean-energy-security-initiative. Connect 2022 intends to create electricity interconnection.44Connect 2022, launched in 2012 by Colombia’s former Minister of Mines and Energy Mauricio Cardenas and US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton, is an initiative involving all the governments in the Western Hemisphere to achieve electrical interconnection and improve access throughout the hemisphere by 2022. See US Department of State, “Connecting the Americas 2022,”http://www.state.gov/e/enr/c52654.htm. The State Department’s Energy Governance and Capacity Initiative (EGCI) aims to foster sustainable indigenous development in certain countries.

The United States now possesses an opportunity to apply its energy endowment to transition regional influence away from Venezuela and reorient the region toward a more prosperous, sustainable, and environment friendly economic development trajectory.

In the immediate term, enhanced access to US natural gas can play a key role in helping replace more expensive, less efficient fuels for electricity generation. Access to proximate US crude oil can help provide cost competitive crude supplies to the region’s refineries. It has been suggested that US light oil would be a natural fit for the simple refineries of Latin America, which cannot use the heavy, sour crudes that can be processed more efficiently in the complex refineries on the US Gulf Coast.45Fitzgibbon and Rogers, “Implications of Light Tight Oil Growth for Refiners in North America and Worldwide,” op. cit. US exports of diesel and gasoline to Latin America are already helping to mitigate some of the shortages of oil products currently facing the economies of South America.

North America

In North America, the growth in Canadian oil and gas production and revival of investment incentives and interest in Mexican energy development and reform provides a unique opportunity for the United States to partner with its neighbors to create a North American energy powerhouse. As highlighted by the first edition of the Quadrennial Energy Review, the “changing North American energy landscape presents opportunities for increased integration of markets and policies to further energy, economic, and environmental objectives.”46Quadrennial Energy Review: Energy Transmission, Storage, and Distribution Infrastructure, April 2015, pp. 6-3.

Three key areas of cooperation are energy trade to make both US and Mexican energy systems more efficient and robust, support to Mexico’s new energy development in the areas of improving investment conditions, safety and sustainable energy development, and enhanced trade and connection in gas and electricity.

First, the United States can help make Mexico’s refineries more effective, less carbon intensive, and more profitable by allowing Mexico the same standing as we give to Canada to buy US oil.47Like most refineries in Central and South America and the Caribbean, and unlike refineries on the US Gulf coast, refineries in Mexico are not equipped with the more advanced equipment and processing facilities needed to handle and refine heavy, sour crude oil. Importing light crude oil from the United States would help enable Mexican refiners to operate more effectively and produce a slate of lighter petroleum products. Such a policy signal could enable collaboration and infrastructure expansion and provide a mix of crude oil better suited to Mexico’s refineries.48Ebinger and Greenley, “Changing Markets, Economic Opportunities from Lifting the US Ban on Oil Exports,” op. cit. 49Kevin Book, Clearview Energy Partners, presentation at the Atlantic Council, June 2015. To fully benefit from the opportunity for a greater North American energy market, the US government should facilitate greater infrastructure and policy integration, including cross-border pipelines like the Keystone XL.50Already, energy trade and infrastructure links among the three North American countries are expanding to take advantage of arising transport and market efficiencies associated in part with development of oil and gas shale and Canadian oil sands development.

Second, as the Quadrennial Energy Review identified, greater integration of US and Canadian electricity systems will allow for cross-border assistance for emergency response, which has clear security benefits and could be expanded to the US-Mexico border.51Quadrennial Energy Review: Energy Transmission, Storage, and Distribution Infrastructure, April 2015, pp. 6-10.

Third, Mexico needs massive investment across the energy value chain to capitalize on its resources. Technical assistance and greater participation by US and Canadian companies in oil and gas development could help development of Mexico’s shale and deepwater as well as conventional oil and gas resources. Such collaboration would flow from higher incentives for investment and lead to higher energy production in all three countries and further the ability of North America to improve regional and global market stability by providing stable supplies of oil and gas.

Economic and market benefits of the US energy boom

As we have noted, US foreign policy is grounded in a strong domestic economy. Throughout our history, mitigating oil price shocks has been important to achieving macroeconomic stability. Today, sustaining competitive energy markets and maintaining a strong energy production base is an important source of US GDP growth. The added step of allowing expanded exports of oil and gas would help maintain a strong US base in energy production.

We highlight five collateral benefits of the US energy boom that impact the US economy or our role as global economic power: 1) the impact of energy production on the US economy (and the linkage of exports to further production growth), 2) the impact of US energy export policy on our current account deficit and on the US ability to meet its export goals, 3) the disproportionate impact of US oil and gas exports on regional or product markets, 4) the impact of US production and exports on price volatility, and 5) the impact on global energy investment conditions.

In addition we considered the impact additional US oil and gas production could have on US environmental imperatives, and detail why we think the United States can harmonize both objectives.

Improve the US economy and economic competitiveness

Greater energy production clearly provides greater net benefits to the US economy. In a major study conducted by NERA Economic Consulting on the economic benefits of lifting the US crude oil export ban, NERA assesses in its reference case that lifting the crude oil export ban would raise GDP by 0.4 percent in the year the ban is lifted and the additional net present value of GDP during 2015-35 would exceed $550 billion, compared to the impact of keeping current policies in place.52NERA Economic Consulting, Economic Benefits of Lifting the Crude Oil Export Ban (September 2014). Lifting the oil export ban would also provide about 400,000 new jobs annually, 25 percent higher pay for workers in the supply chain—about $158 per household—and $1.3 trillion in federal, state, and municipal revenue from corporate and personal taxes, according to IHS.53IHS, Unleashing the Supply Chain (March 2015). Although oil price changes since the NERA study was concluded in September 2014 might dampen the economic benefits somewhat, few actions available to the US government could benefit the economy this much. Absent a change in policy, we will forgo these economic benefits.54In particular, oil prices are lower than in September 2014 and the price spread between Brent and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crudes has narrowed, as Brent-quality crude imports to North America have been displaced by rising output of US light crude oil, reducing Brent prices, and WTI prices have increased as infrastructure constraints to transport and refine US crude oil have eased. EIA, “Short-Term Energy Outlook,” Market Prices and Uncertainty Report (July 2015), http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/steo/uncertainty/.

Unless the United States lifts export restrictions, US light oil production growth soon could be so much greater than US demand or refining capacity that prices jeopardize the continuation of the US shale oil revolution.

The lack of an export outlet for oil will limit production once we reach the “day of reckoning” or the point when existing outlets for light oil are saturated and the price discount required to make light oil useful to domestic refineries is below the level at which it is economic to produce. 55EIA, Technical Options for Processing Additional Light Tight Oil Volumes Within the United States (April 2015), http://www.eia.gov/analysis/studies/petroleum/lto/. Prices for light sweet crude already have dropped relative to international levels. Unless the United States lifts export restrictions, US light oil production growth soon could be so much greater than US demand or refining capacity that prices jeopardize the continuation of the US shale oil revolution.

Maintain the US commitment to free trade

The United States is a major trading nation and has led in setting the rules for the World Trade Organization (WTO), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and nearly every major global trade agreement. US officials frequently argue that nations that do not have scarcity of natural resources should not withhold them from the global market.56Carlos Pascual, IHS, testimony in front of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Hearing on US Crude Oil Export Policy, March 2015. A US failure to practice what it has preached for decades with respect to its energy endowment reduces US influence in trade talks and serves only to undermine long-held goals. Additionally, it is important to note that some of the proposals may leave the United States open to World Trade Organization suits.

Increase competitiveness of global and regional energy markets

While the volume of US oil and gas exports might not be large in terms of the global market, it can be significant to volumes actually traded and especially to destination markets, providing outsized impacts. According to analysis by Citibank, US gas exports to Mexico could reach 6 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d) in 2020, which is only 7 percent of the US market but more than 50 percent of Mexico’s gas supply. US condensate production could approach 2 million b/d in 2020, with a naphtha content of about 1.6 million b/d, which could account for roughly 20 percent of the global market for naphtha by 2020, according to the Citibank study. (Notably Iran is a significant condensate producer and exporter). US export capacity for liquid petroleum gas (propane and butane) should reach 1 million b/d by 2016, which will be roughly equivalent to about 12 percent of global demand. This could have a particularly large impact on the global petrochemicals sector.57Ed Morse et al., Energy 2020: Out of America, The Rapid Rise of the United States as a Global Superpower,(Citi, November 2014). https://www.citivelocity.com/citigps/ReportSeries.action?recordId=30.

US LNG exports could reach 8-10 bcf/d in 2020 according to the Citibank study,58Ibid. amounting to roughly 10 percent of the US gas market but 20 percent of the global LNG market. Even before the United States approved new LNG export projects, planned LNG imports to the United States displaced by increased US domestic production lowered global LNG prices and eroded oil-linked pricing in Europe and Asia. Recently, Henry Hub-linked LNG pricing has challenged the status quo of natural gas exports and has provided a hedge against oil prices for LNG importers. As the availability of LNG exported from the United States continues to grow, global market prices for LNG should become increasingly more competitive.

The United States can—and should—maintain the dual goals of assuring energy security for its allies and trading partners while supporting efforts to help the world address climate change.

Enhanced US participation in crude oil markets would have an equally powerful competitive effect by lowering Brent prices, increasing the diversity of supply available to European and Asian buyers, and reducing price volatility.

US crude oil exports of 3 million b/d, for example, would represent only about 3 percent of global supply but constitute about 5 percent of all traded crudes and a much higher percentage of traded light crudes.59The figure of 3 million b/d of US crude oil exports is posited as a possible future volume of US crude oil exports if the export ban is lifted. IHS projected in 2014 that with free trade US crude oil production would rise to a peak of 11.2 million b/d in 2022 in its Base Production Case and to 14.3 million b/d in 2025 in its Potential Production Case, which assumes higher spending than the Base Production Case. See IHS, US Crude Oil Export Decision (2014). By comparison, the North Sea provided only about 5 percent of global supply during the 1980s when North Sea oil supply was one of the key factors undermining OPEC’s ability to raise oil prices.60BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2015, http://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/pdf/Energy-economics/statistical-review-2015/bp-statistical-review-of-world-energy-2015-full-report.pdf. US producers also have a quicker ability to bring production online, as shown by the rapid increase in shale gas production.

Stabilize and reduce volatility of global markets

The abundant US resource base can help to stabilize markets in two primary ways: as a surge producer, with quicker time to market than other global producers, and through strategic measures designed to stabilize the market short term in times of emergency. The first can be achieved through increasing the volume of reliable, cost-competitive energy supply available on the market through exports (addressed in the prior section). The second is through the utilization of emergency response mechanisms like the US strategic petroleum reserve and the IEA’s Coordinated Emergency Response Mechanism (CERM).

Originally designed to protect the US economy and consumers from oil supply disruptions, the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) remains an unequalled strategic asset. The United States should assure that the SPR can be used effectively to deploy oil to the global market by ensuring that the infrastructure needed for withdrawals is up to par, and that the triggers for release reflect the changes in the energy market since its inception. On a global scale, as Europe’s strategic reserves decline in proportion to their import coverage needs, the United States and its IEA partners should discuss ways that the CERM stocks and release mechanisms can be modernized as well. As the United States considers modernizing the SPR, it should consider the benefits of creative solutions, such as considering ways that IEA members or non-member affiliates can share in US SPR supplies.

Finally, today’s energy demand picture has shifted significantly enough that the IEA CERM, which only includes OECD nations, does not include the primary drivers of energy demand today—all of whom are in the developing world. It is vital that new or enhanced emergency response mechanisms are developed to address supply disruptions that include countries outside of the OECD. If major consumers like China and India prefer not to join in the IEA CERM, developing a new structure that would allow for coordinated action would benefit all of the involved parties.

Incentivize improved investment conditions globally

The success of the US energy boom and increased competition from US exports can also improve the global investment environment for oil development and enhance the efficiency of other non-OPEC suppliers, adding to market resilience and diversity. By expanding energy investment at home, the United States puts pressure on other producers to improve investment incentives and conditions to attract greater investment in their energy development. This includes pressure on other countries to honor contract sanctity, improve transparency, reduce corruption, and reduce price subsidies for domestic energy consumption. In short, US expanded opportunities to invest in energy development in the United States changes dynamics everywhere.61Matthew Sagers, IHS, presentation to the Atlantic Council, May 2015.Sarah O. Ladislaw, et al., New Energy, New Geopolitics (CSIS, April 2014).

Support cleaner energy production

The United States can—and should—maintain the dual goals of assuring energy security for its allies and trading partners while supporting efforts to help the world address climate change. Indeed, the United States has successfully increased renewable energy shares and hydrocarbon production shares over the past ten years.62EIA, “Table 1.2, Primary Energy Production by Source,” Monthly Energy Review (June 2015), http://www.eia.gov/totalenergy/data/monthly/pdf/mer.pdf.

The upstream carbon effects of increased production from lifting the crude oil ban or expanding LNG exports are difficult to calculate. Only a portion of the increased US production, perhaps half, would be added to the global supply. It should be noted that US production occurs under some of the strictest environmental safeguards on the planet, irrespective of concerns over emissions.

Easing export policies will not deter the United States and other countries from exploring efficient methods of reducing carbon dioxide emissions. Increasing access to natural gas for economies that currently rely on more carbon-intensive sources, for example, will help reduce their emissions. Deploying nuclear power and renewable energy, coupled with increased energy efficiency, can also make a significant contribution to improving national and global energy security. Outside of the United States, opportunities for efficiency gains are especially large in countries such as Egypt and Ukraine, which have had large subsidies that promote over-consumption of energy. To facilitate these changes, credible policies are needed at home and abroad to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. As these domestic and international objectives are pursued, allowing US oil exports can provide stability to global markets without affecting the growth of renewables since oil accounts for such a relatively small share of electricity generation in the United States.63According to the EIA Annual Energy Outlook 2015, petroleum and other liquids only account for 1 percent of US electricity generation.

Recommendations

US energy abundance is a new and powerful foreign policy asset, remarkable after decades of scarcity, and offers a new element of US national strength. It enhances our role in the world and provides us with the power to make energy markets more competitive and resilient. Combined with our technological prowess and policy tools, we can dramatically enhance our ability to address foreign policy challenges abroad—if we choose to leverage this power. Any effective energy security strategy must combine demand-side measures with supply-side strategies. We see no contradiction between assuring diversity of supply and promoting the increased use of renewable energy sources, enhanced energy efficiency strategies, and improved fiscal measures such as reducing inefficient energy subsidies.

Lift the ban on crude oil exports, while retaining presidential authority to add restrictions when in the national interest.The consensus of our task force experts is that the arguments for lifting the crude oil export ban are very strong, based on economic, security, and fair trade principles. Moreover, the combination of these elements would increase US strength and leadership capabilities that are essential to optimizing the foreign policy benefits of the energy boom to a wide range of security and geopolitical interests. Broad action to lift the ban and let the market dictate the destination of US crude oil exports is preferable to piecemeal actions. Achieving this will require educating the public on several points, including: (1) the net benefits that would flow to the United States from expanding export markets and US economic growth; (2) US gasoline prices would not be affected by allowing exports; and (3) failing to lift the ban harms our efforts to aid allies and address risks emanating from Russia, the Middle East, and Asia. We see this as a major leadership challenge but one that the Congress and the Executive branch are up to. We recommend the President determine crude oil exports to be in the national interest under EPCA, which does not require Congressional approval. We believe that Congress should fully repeal the outdated prohibitions.

Further lift export restrictions on LNG, while preserving the environmental and safety review process.Our task force experts see the chief benefits of US export of LNG as providing the enhanced diversification, competition, and energy security for global and regional markets through the expansion of the overall volume of global LNG supply. For these purposes, the more LNG exports the better for our foreign trading partners. We believe that US gas supply is now so robust that all LNG exports should be deemed to be in the national interest, regardless of free trade agreement status. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) should still ensure that all environmental reviews are performed as required and the Department of Energy should retain the power to change its determination under the Natural Gas Act if market conditions should subsequently change. What matters most is not directing the additional LNG supply to specific destinations, but adding to global supply. This way, all countries can benefit from price competition and pressures to delink gas prices from oil prices. This measure strengthens the incentive for US producers to invest in gas production, without having a large impact on US consumers because of the added costs of liquefaction, transportation, and re-gasification that have to be paid by foreign customers to import LNG from the United States.

Conclude the TPP and TTIP negotiations without restrictions on access to US energy exports. US allies and trading partners already are clamoring for access to LNG and crude oil exports from the United States, including asking that LNG and crude oil be included in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).64EC Directorate General for Internal Policies, TTIP Impact on European Energy Markets and Manufacturing Industries (January 2015), http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/536316/IPOL_STU(2015)536316_EN.pdf. We believe that a direct removal of restrictions on oil and gas exports is the most efficient path to addressing energy access for our trading partners. A failure of TTP and TTIP would be a setback for US relations with European and Asian allies and trading partners, and negate some of the potential economic and foreign relations benefits of the US energy boom.65Rem Korteweg, “It’s the Geopolitics, Stupid: Why TTIP Matters,” Center for European Reform, April 2, 2015, http://www.cer.org.uk/insights/it%E2%80%99s-geopolitics-stupid-why-ttip-matters.

Support energy diplomacy and technical assistance. US energy diplomacy is practiced within a number of federal agencies, including the US Department of Energy, State Department, Agency for International Development, Department of Commerce, US Trade Development Agency, Export-Import Bank, and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation. Energy diplomacy and assistance is an effective means to help improve energy security abroad by encouraging and facilitating multi-country projects, boosting supply, improving energy efficiency, and managing energy systems. US-European energy security strategy has long combined these approaches with important success.66Georgia, for example, benefited from US and European help in negotiating new pipelines from Azerbaijan through Georgia to western markets, from technical assistance in rehabilitating and expanding its hydroelectric plants and an array of measures to improve energy intensity, including reducing subsidies, installing electric meters, and raising collections of payments for energy use. Ukraine and others could benefit from similar assistance, from assistance in unconventional oil and gas development, and from a variety of diplomatic initiatives to assist energy-poor countries and to coordinate responses to supply disruptions. These programs should be funded to support the market and regulatory advice that will be needed to address energy insecurity concerns abroad. The Senate should confirm an Assistant Secretary of State for Energy and Natural Resources.

Combat global energy poverty by encouraging the development of affordable and reliable energy systems that include both traditional and renewable sources.Some 1.3 billion people—18 percent of the global population—lack access to electricity.67Hillary Clinton speech at Georgetown University, op cit. Many more lack dependable supplies of electric power. The challenge of developing power systems that can combine the use of renewables with the use of more traditional fuels that provide baseload and back-up power is a major impediment to the expansion of affordable electricity. Expanding grids to share the costs of back-up power is one solution, but it requires access to credit, planning, and technical assistance that that the United States can help provide. Emerging economies in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean are most in need of such assistance.68IEA, World Energy Outlook 2014. In addition, distributed renewable power, in particular to replace expensive diesel generators and unhealthy firewood is needed. The United States can leverage energy diplomacy and strong US technological innovation to help countries address these matters.

Sustain research and investment into energy storage, renewables, CCS, and other critical technologies.Recent advancements in energy storage technology—especially super batteries—have the potential to make renewable energy sources such as solar and wind a viable alternative to fossil fuels. CCS could play an important role in reducing GHG emissions. The United States has a rich history of research and investment that needs to be sustained—especially at the national labs—to further advance these and other technologies to increase energy availability, efficiency, and affordability, and reduce GHG emissions. Application of these technologies also needs to be pursued aggressively, especially through incentives and requirements that promote energy efficiency.

Consider ways to expand the collective energy security system to include more producers and consumers, especially China and India—which are developing strategic stocks—and trading partners with insufficient strategic stocks to address a supply disruption. Countries outside the IEA account for more than half of the world’s energy consumption and will account for almost all growth in energy demand up to 2030, according to the IEA. The IEA now has close relationships with key countries outside the IEA, including Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Thailand, as well as some key Caspian, Middle Eastern, and North African energy producers.69IEA, “Non Member Countries,”July 2015, http://www.iea.org/countries/non-membercountries/. But more is needed to include the largest consumers—especially China and India—in energy emergency plans, including response plans for major supply disruptions. China is the only country outside the IEA that holds major volumes of strategic oil stocks. India recently approved a budget of $338 million to create a strategic reserve, according to the IEA.70Javier Blas, “IEA Sees China, India Filling Strategic Reserves with Cheap Oil,”Bloomberg, March 2015, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-03-13/iea-sees-china-india-filling-strategic-reserves-with-cheap-oil. No other country outside the IEA holds major volumes of strategic stocks, leaving a large number of US trading partners highly vulnerable to supply shocks. The United States should work with these countries and within the IEA on ways to strengthen ties and better prepare for such shocks, including selling drawing rights to stocks held in the United States or elsewhere.