November 4, 2021

What future for the Western Sahel?

Pour lire la version française de ce rapport, cliquez ici.

A recording of the official launch event is available here.

The region’s demography and its implications by 2045

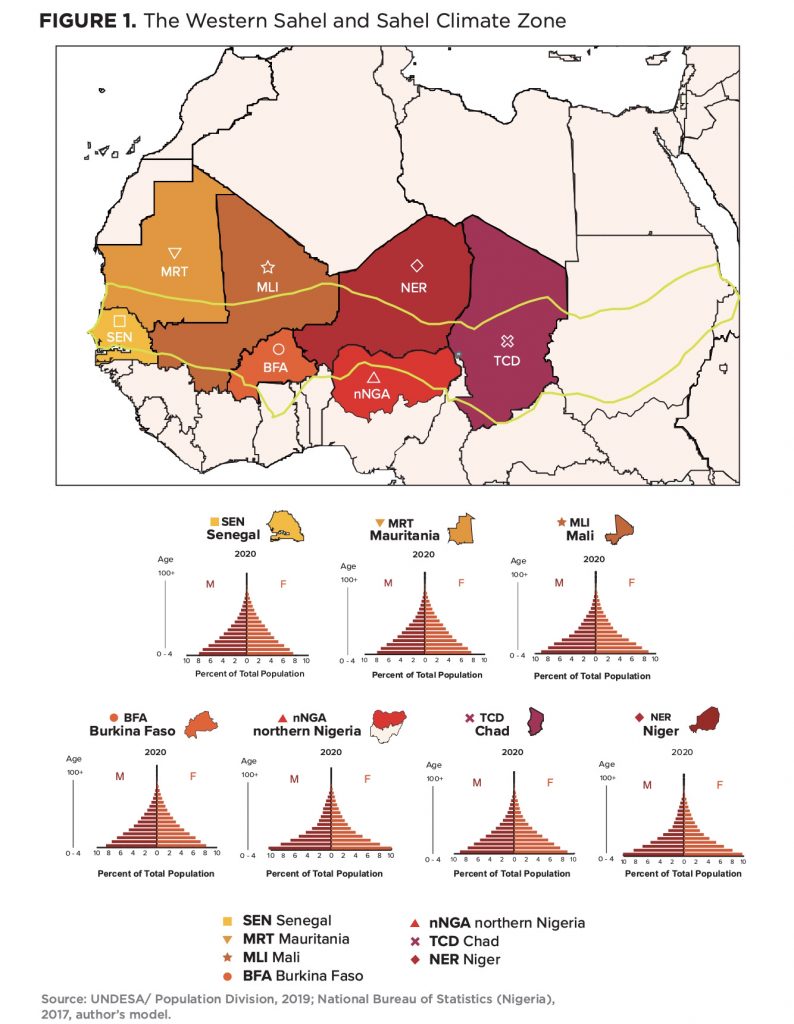

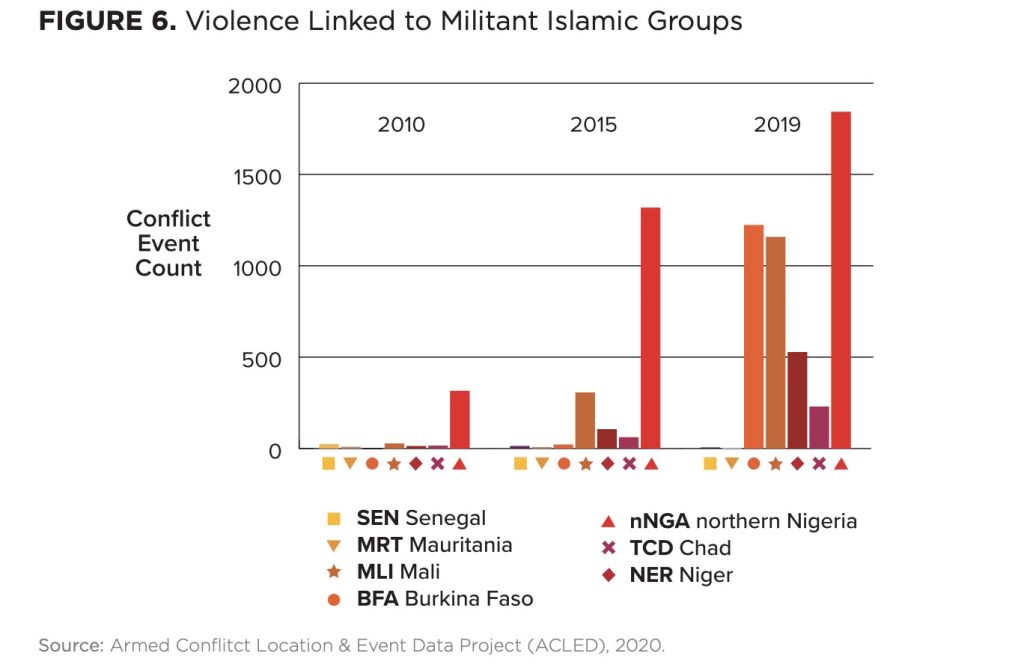

The Western Sahel—a region stretching from Senegal and Mauritania to Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad, and including the twelve sharia law states of northern Nigeria—is in a demographic impasse. Rather than yielding an economic dividend, the conditions spawned by the region’s persistently youthful, rapidly growing, high-fertility populations overwhelm the capabilities of state-run services, generate extensive urban slum conditions, slow if not stall economic and social progress, and aggravate ethnic tensions. Decades of exposure to these mutually reinforcing conditions have undermined the legitimacy of central governments and rendered the region’s states vulnerable to the spread of Islamic populism and regime instability.

Due to the growth momentum of their youthful age structures, from now through the 2040-to-2045 period (the time horizon of this study), the region’s states will be driven to respond to the urgent needs to build infrastructure, increase agricultural productivity, maintain security, and generate jobs in their attempt to employ and politically pacify young-adult cohorts of unprecedented size who, each year, vie to enter the already underemployed Sahelian workforce. Yet these well-intentioned development efforts can never be sufficient unless the region’s governments prioritize policies and programs that address a key underlying impediment to development: sustained high fertility.

To work their way out of this dilemma, Sahelian governments must shift a significant part of their development focus and funding to policies and programs aimed at preventing adolescent marriages and childbearing, promoting girls’ education, securing women’s participation in public- and private-sector workplaces, and achieving small, healthy, well-educated families. However, the region’s persistent jihadist insurgency raises questions as to how far women-centered programs can be safely and successfully extended beyond the edges of the Western Sahel’s inland cities. Absent serious progress on these coupled crises, policy makers in the EU, the United States, and their non-European allies may eventually disengage (as they already have from Somalia today), concluding that containing the Western Sahel’s jihadist insurgency and out-migration at the region’s frontiers is a more viable option than continued development assistance.

Adjoining discussion paper: Regional policy and program perspectives

To gain further insights and cover policy and program issues that extend beyond the authors’ expertise, the Atlantic Council’s Foresight, Strategy, and Risk Initiative commissioned Organizing to Advance Solutions in the Sahel (OASIS), a reproductive health policy organization based in Berkeley, California, to convene a series of consultative discussions among West African public health and education professionals. These professionals discussed the merits of current policy and programmatic approaches in the Sahelian states, identified the major obstacles encountered, and recommended areas for additional effort and investment. A synopsis of these consultations appear in the OASIS discussion paper titled “Accelerating a Demographic Transition”. An additional analysis of international assistance to the Sahel for reproductive health and girls’ education is available in an accompanying OASIS brief. Several of their key points are discussed and cited in this report.

Key findings

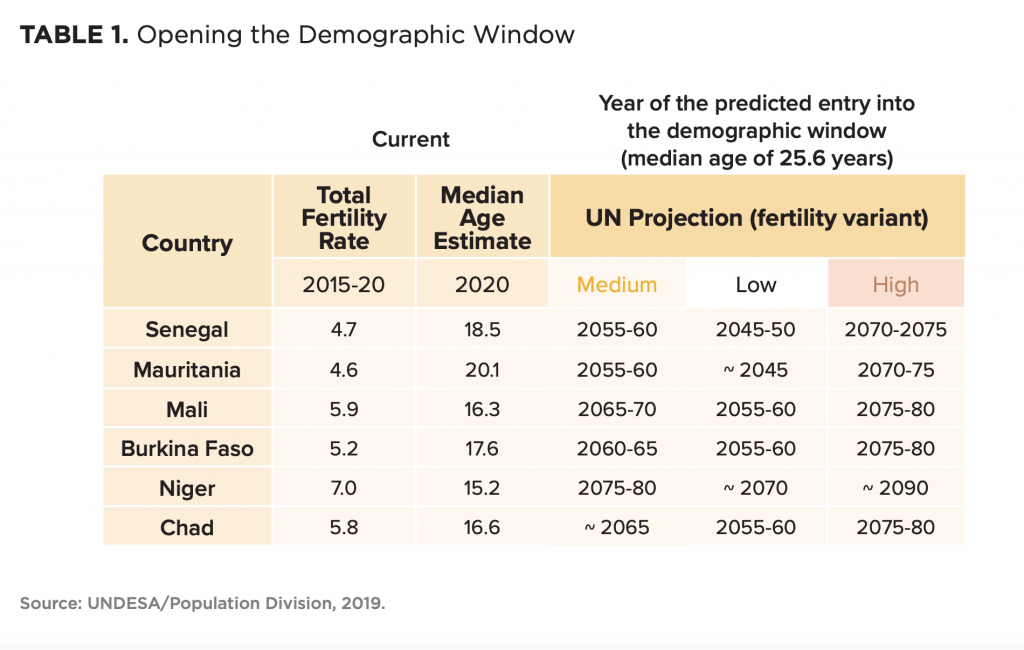

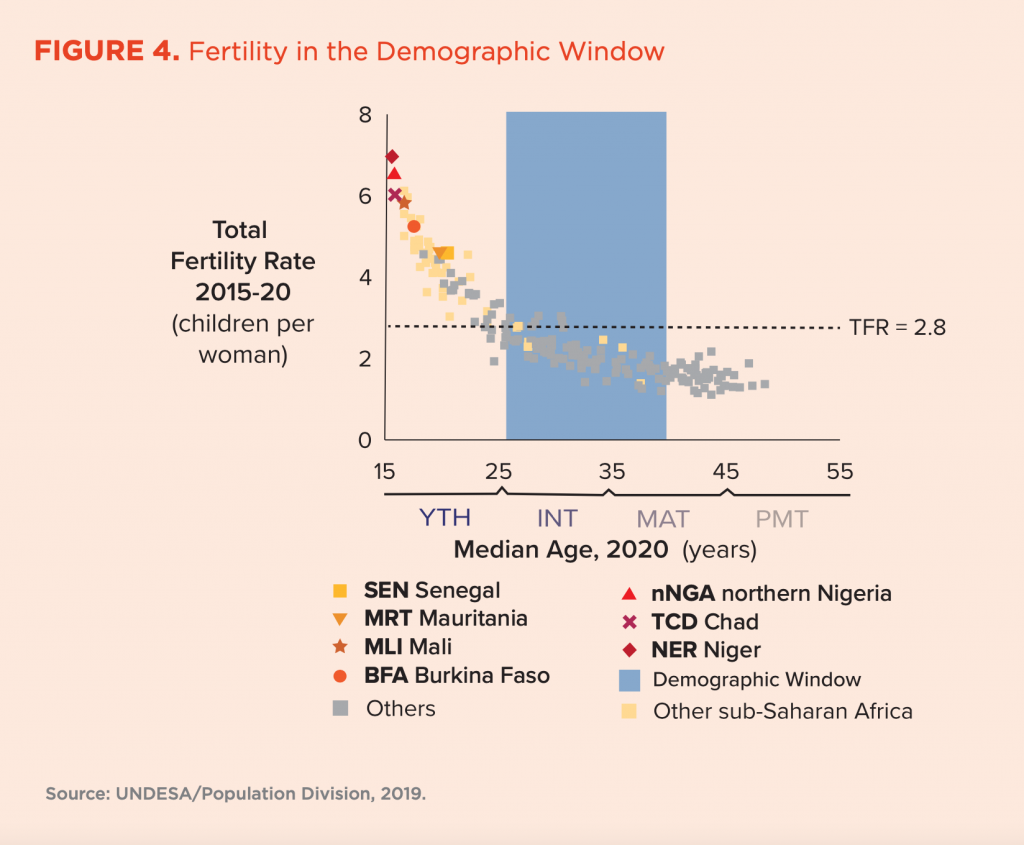

Age structure and the demographic window. As a group, the Western Sahelian countries remain among the world’s most youthful populations. Moreover, within the 20-to-25-year period of this report, none of the Western Sahelian countries are projected by the United Nations (UN) Population Division’s medium-fertility projection to reach the demographic window, namely a period of socioeconomically and fiscally favorable age structures (the so-called demographic dividend). Over the past seventy years, it has been within this window—beginning at a median age of around 25 or 26 years—that countries generally have reached upper-middle levels of development (e.g., the World Bank’s upper-middle income category and associated levels of educational attainment and child survival). Notably, Mauritania and Senegal will approach this demographic window by 2045 in the current UN’s low-fertility projection—the most optimistic scenario in the Population Division’s standard series.

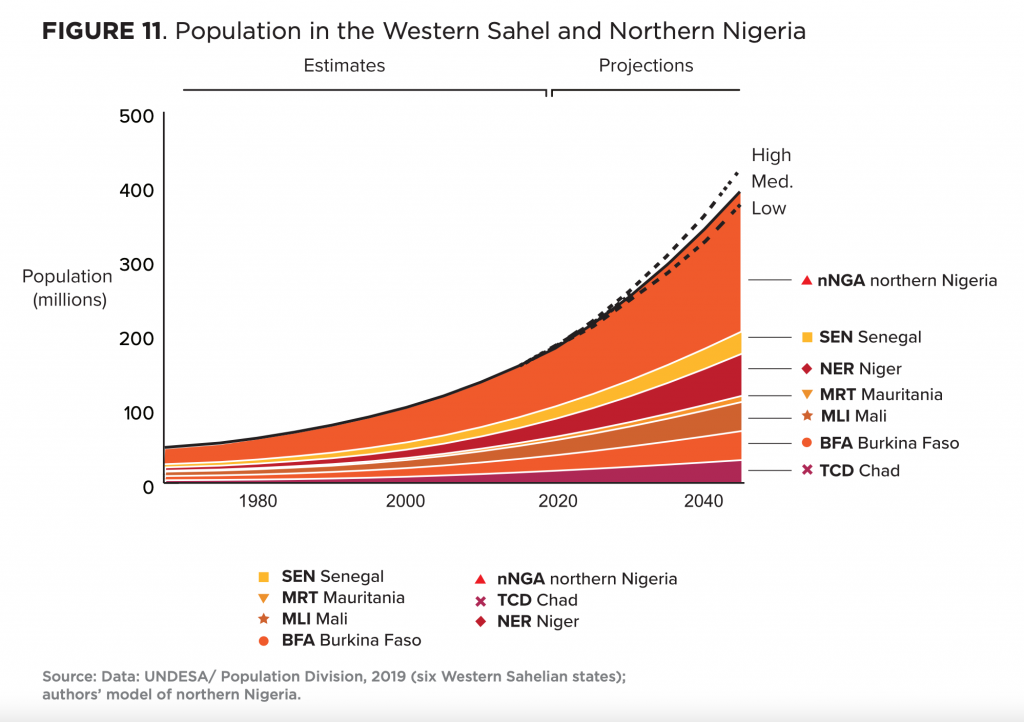

Population growth. UN demographers estimate that the overall population of the six states of the Western Sahel has grown from nearly 21 million inhabitants in 1960 to about 103 million in 2020—an almost five-fold increase over sixty years. For the twelve states of northern Nigeria, the authors’ modeled estimates suggest that the population trajectory has been comparably steep, reaching nearly 78 million in 2020. Those sources expect the combined populations of the six Western Sahelian countries and northern Nigeria to grow from today’s estimate of about 181 million to somewhere between a projected high, in 2045, of about 415 million, and a projected low of about 370 million people. Much of this growth is produced by age-structural momentum, a largely unavoidable consequence of the region’s extremely youthful age distribution.

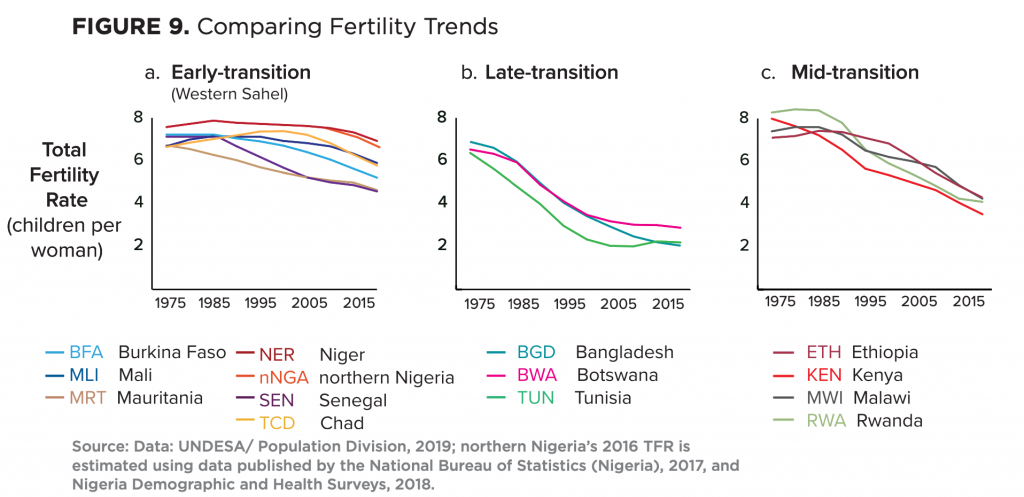

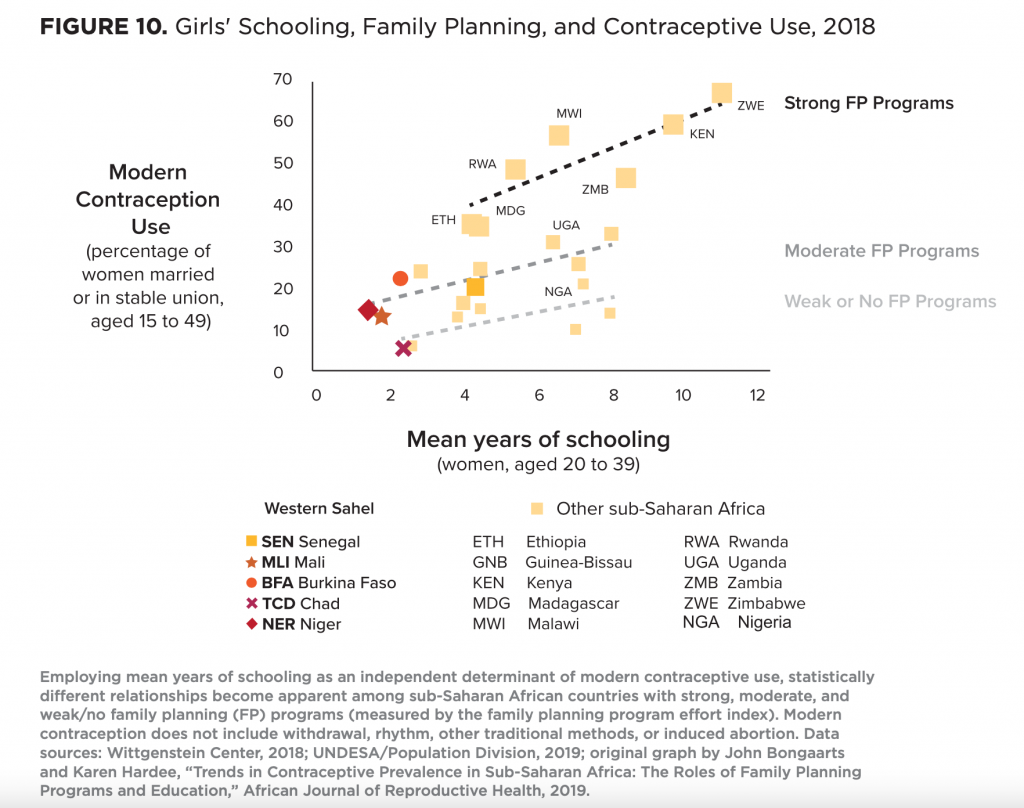

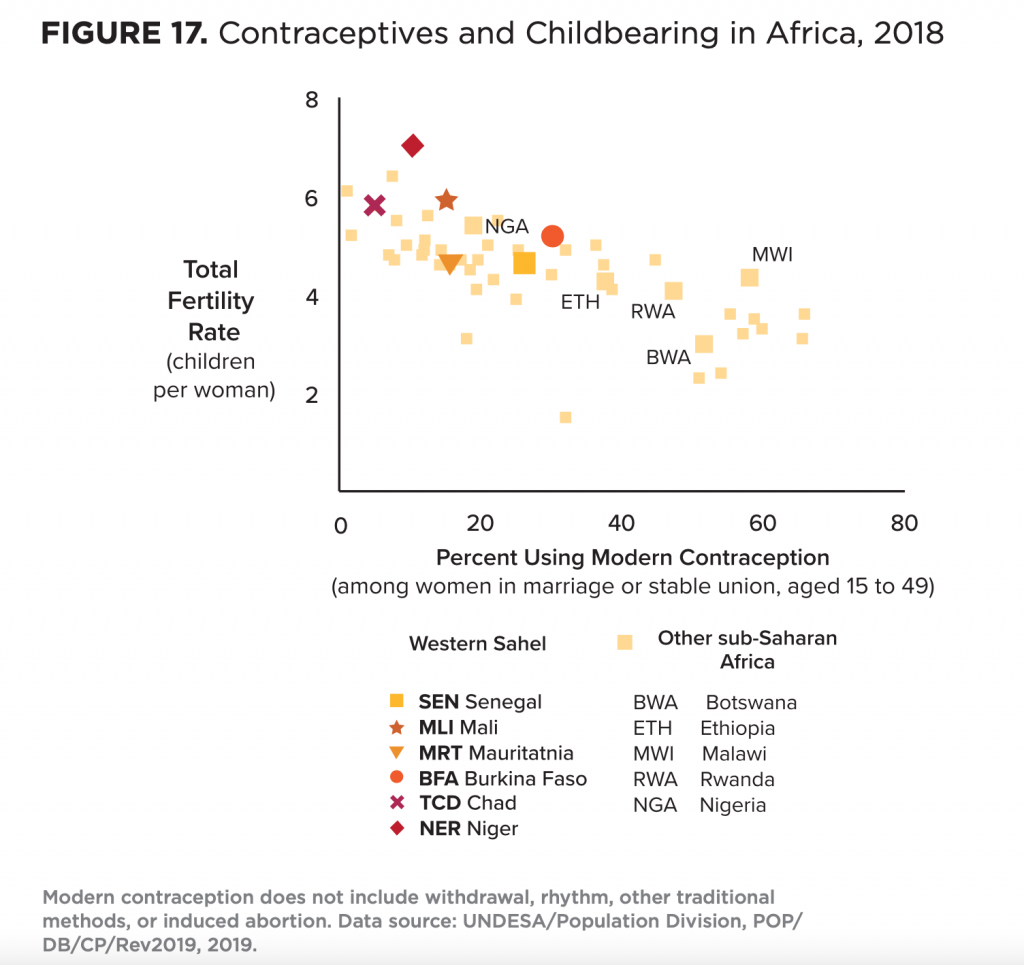

Fertility decline. The region’s total fertility rates currently range between about 4.6 children per woman in Senegal and Mauritania, to pretransition rates—above 6.5 children per woman—in Niger and the twelve sharia law states of northern Nigeria. Throughout the Western Sahel, rates of adolescent childbearing remain extremely high, and ideal family size generally equals or exceeds realized fertility. Even in the recent past—up to and including the UN’s 2010 data series—the Population Division’s medium-fertility projections for the countries of the Western Sahel have proved overly optimistic. Yet, recent local surveys in the region indicate that the current version of its medium-fertility projection is not out of reach. That scenario assumes that, between 2040 and 2045, fertility will decline to between 3.4 and 4.0 children per woman in most of the Western Sahel’s states, and near 4.7 in Niger. Significant differences in modern contraceptive use and patterns of childbearing are already evident between rural women and more educated urban women, but the differences are not yet as pronounced as in East or southern Africa, where fertility decline is proceeding at a faster pace.

Maternal and child health, as well as girls’ education. Whereas childhood mortality has steadily declined in the Western Sahel, still one in ten children die before the age of five in Mali and Chad. Recent World Health Organization (WHO) estimates indicate that in Niger and Chad, more than 40 percent of children below age five exhibit stunting. According to the WHO, Chad’s maternal mortality rate is the world’s second highest, while Mauritania, Mali, and Niger are also among the twenty countries in which pregnancy and childbirth are the most dangerous. In Chad and Niger, just one in five eligible girls are enrolled in secondary school, and net secondary enrollment has yet to rise above 40 percent elsewhere in the region. Adolescent marriages remain the region’s most serious deterrent to increasing girls’ educational attainment.

Women’s autonomy and rights. Despite the advice of regional health professionals and the criticisms of UN agencies, successive governments have, so far, done little to enforce already existing laws that would reduce adolescent marriages, eliminate female genital cutting, protect women from forced marriages, restrict polygamy, and give women inheritance rights and custody of their own children in case of marital separation or widowhood. While women’s advocates see these as key to a shift in preferences to smaller, healthier, and better-educated families, current Sahelian political leadership fears political blowback. High levels of organized resistance—such as the large demonstrations by Islamic organizations in Mali, in 2009, that turned back women’s rights—have convinced some development professionals that for several states in the Western Sahel, the only route to change currently available may be through intensive investments in girls’ education and financial support for women’s health care networks, as well as progressive legal, professional, educational, and cooperative societies.

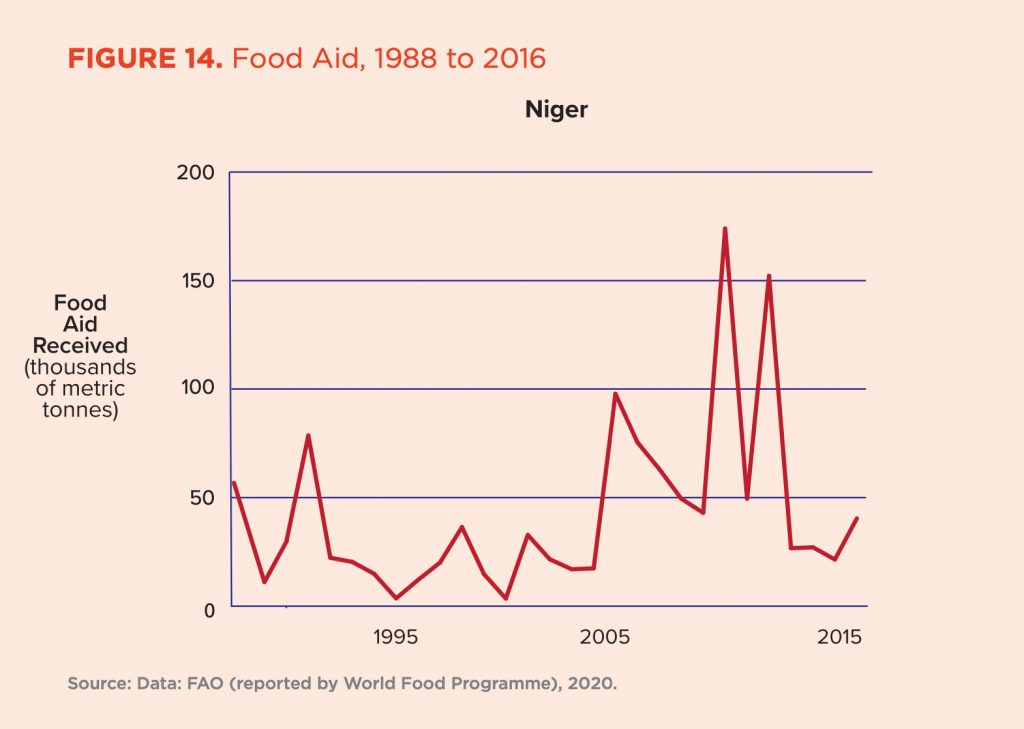

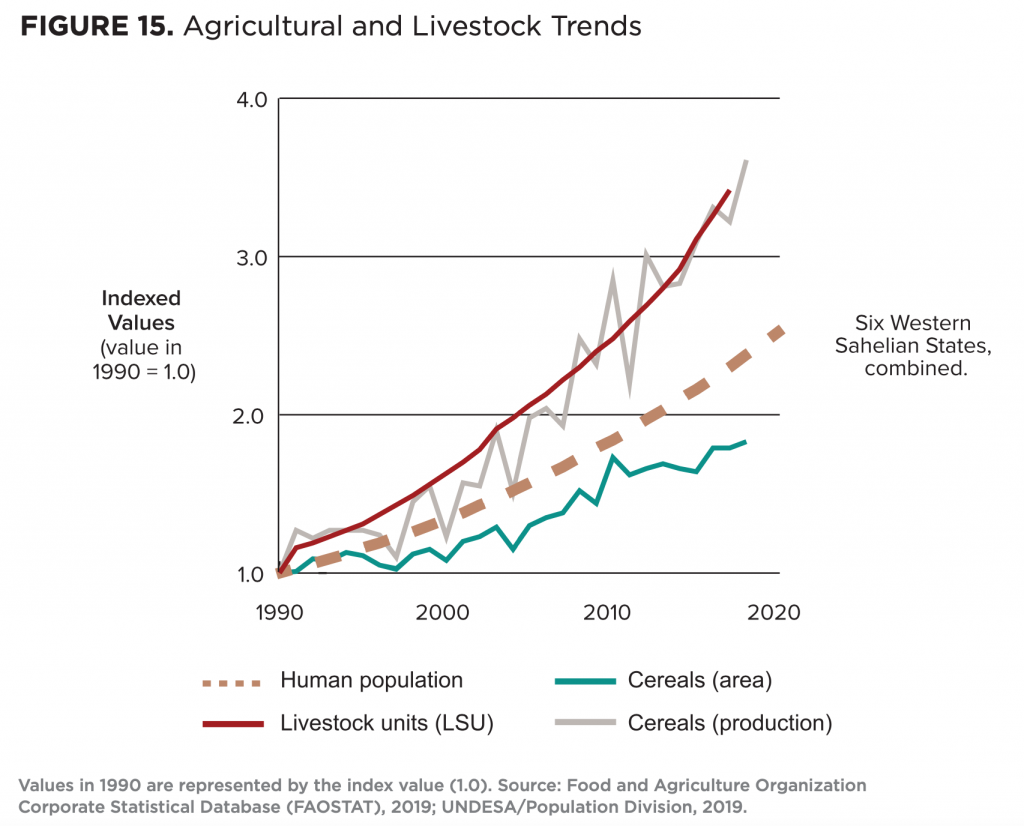

Farming. Despite rising temperatures and the recent slowdown of cropland expansion, the growth of grain production has, since 1990, exceeded the pace of the region’s roughly three percent per year rate of population growth. However, due to erratic harvests on mar- ginally productive croplands, armed conflict, and the presence of displaced populations, the region’s states are regular recipients of substantial food aid. Whereas ground-water irrigation is likely to become a more important input in the future, the combined effects of future population growth, continued climatic warming, persistent insurgency, and periodic drought in the Western Sahel make food self-sufficiency highly unlikely in the foreseeable future.

Pastoralism. After three decades of relatively steady increases in rainfall in parts of the region, livestock numbers (adjusted for species body-size differences) have grown significantly since the 1990s. Yet the most productive pastoral rangelands, put under the plow by growing populations of dryland farmers, have dwindled in surface area. Meanwhile, the numbers of grazing-rights holders have proliferated and vegetation on the remaining rangelands have dramatically deteriorated in form and forage quality, precipitating shifts from cattle to sheep and goats. Across the Sahel, agro-ecologists have noted the emergence of what they call neopastoral production systems that feature wealthy absentee owners of large herds, the proliferation of light but sophisticated weaponry, and a growing impoverished and politically marginalized pastoral underclass that is increasingly vulnerable to radicalization.

Security. The region is in the throes of rapidly growing Islamic insurgencies. Whereas demographic models of persistent non-territorial (revolutionary) conflict predict substantial declines in the risk of such conflict during the demographic window, none of the region’s states are currently projected by the UN Population Division to reach that window during the period of this report. Thus, the authors’ models suggest that ongoing conflicts in Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, Chad, and northern Nigeria are statistically likely to continue, at some level, through the 2040-2045 period. Unlike the Marxist-inspired insurgencies that ignited across Southeast Asia and Latin America during the second half of the twentieth century, the jihadist presence in the rural portions of the Western Sahel restricts the educational progress of women, their autonomy, and delivery of the family planning services that could facilitate fertility decline and improve reproductive health and nutrition.

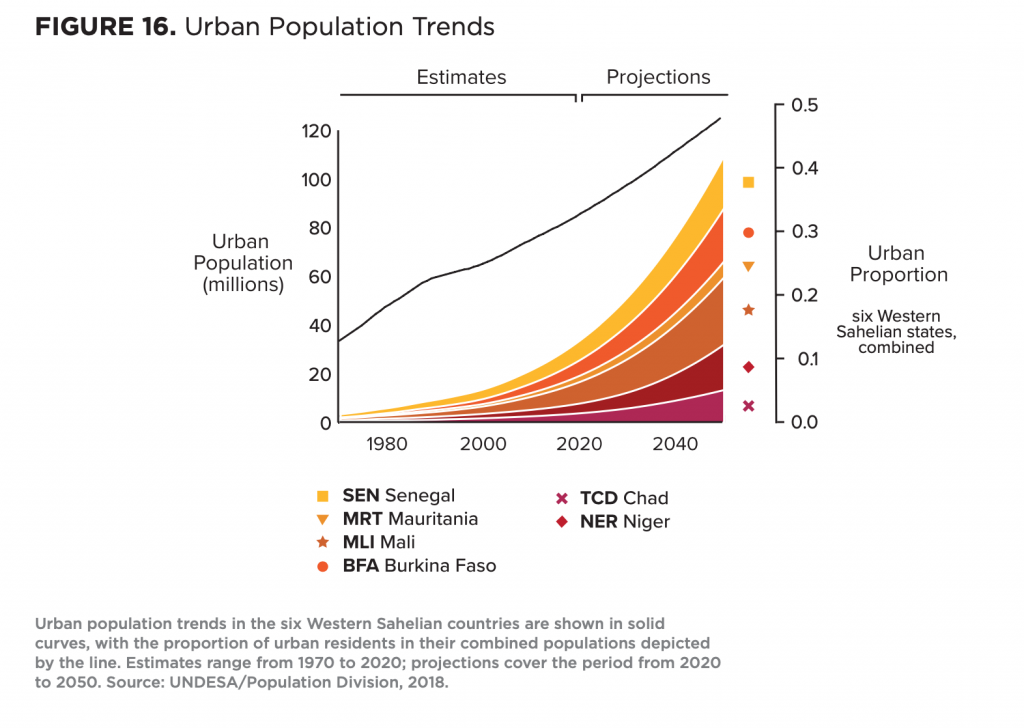

Urbanization. The rapidly growing urban population of the six countries of the Western Sahel currently comprises about one-third of the region’s population and is projected to approach half by 2045. Despite laudable investments in housing that have dramatically reduced the proportion of slum dwellers in the urban population in several states, these efforts have been outpaced by rapid urban growth. Consequently, the region’s slum-resident population has nearly doubled since 1990. As income-generating opportunities evaporate in the agricultural and livestock sectors, the hopes of young men will rest on the urban job market and the educational opportunities that make them fit for employment. Yet employment in the formal sector of the economy will remain elusive throughout the region, and rapid urbanization is bound to present new housing, fresh water, energy, health, sanitation, and security challenges. Still, if governments and donors heavily invest, urban transformation could stimulate transitions to greater female autonomy and smaller, better educated, more well-nourished families with skills and prospects for urban employment in the region.

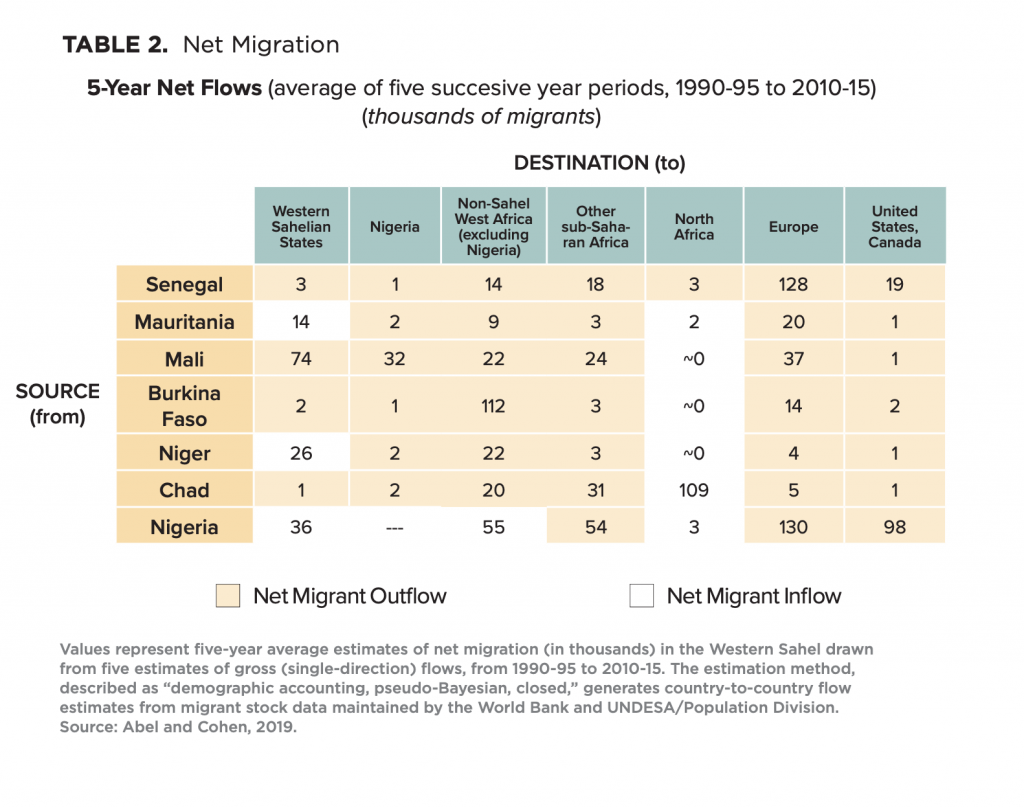

Migration. Between 1990 and 2015, more than 80 percent of migrant flows that originated in the six Western Sahelian countries ended beyond the region’s borders. During this period, slightly more than 60 percent of the net outward flows were added to populations in other African countries, whereas nearly 40 percent were added to populations in Europe, North America, and destinations elsewhere. Senegal and Nigeria in particular, represent significant migrant gateways to Europe and North America. This analysis does not even account for substantial refugee flows during the 2015-2020 period, which are associated with escalating conflict in the Lake Chad Basin, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali. For young Sahelians surviving on marginal rural livelihoods and in urban slums, episodic drought, looming conflict, and sustained economic hardship represent weighty “push factors” that readily tip personal decision-making toward migration. In this arid and poorly developed part of the world, the region’s population size is clearly important. It adds to the ranks of those in marginal livelihoods who might be pressured to leave during episodic disasters and seek greater opportunities elsewhere, while creating few “pull factors” encouraging potential migrants to stay.

Models of demographic progress

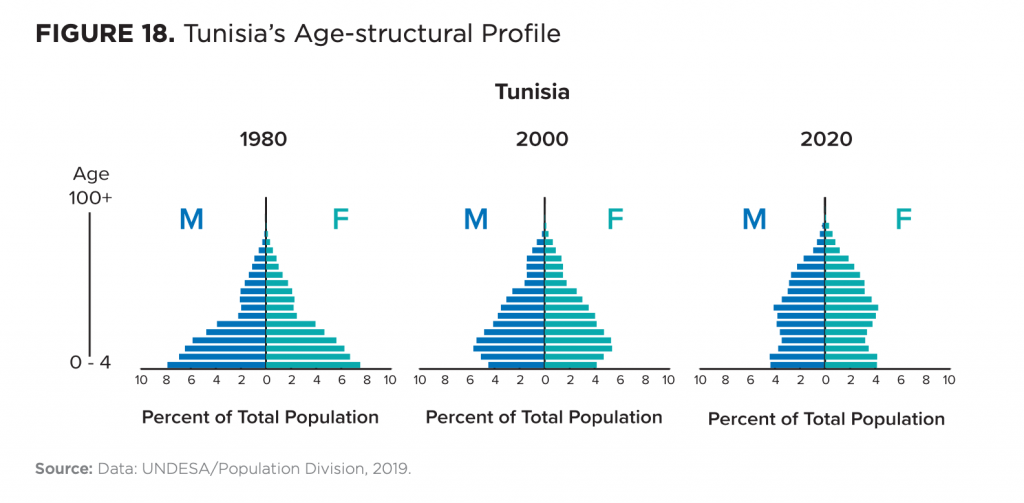

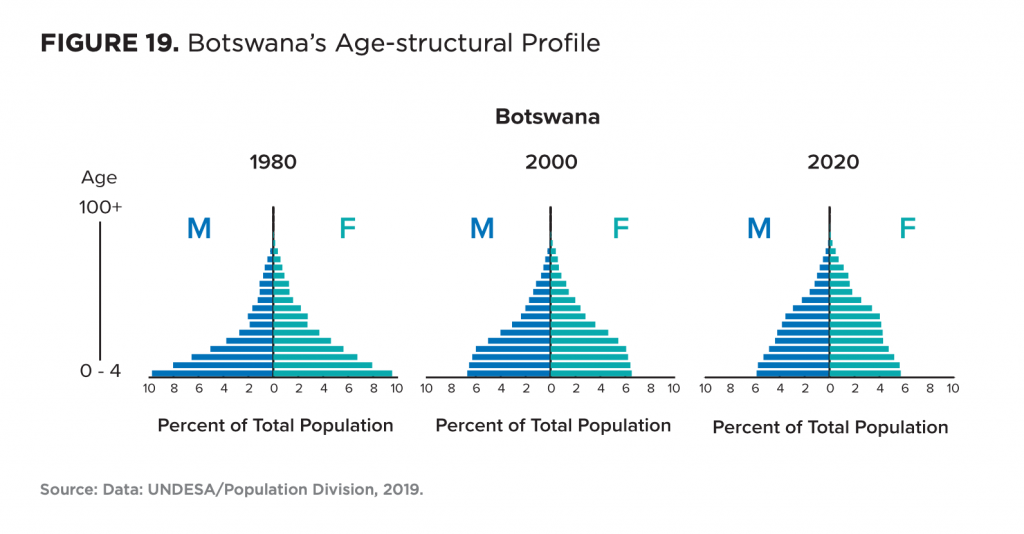

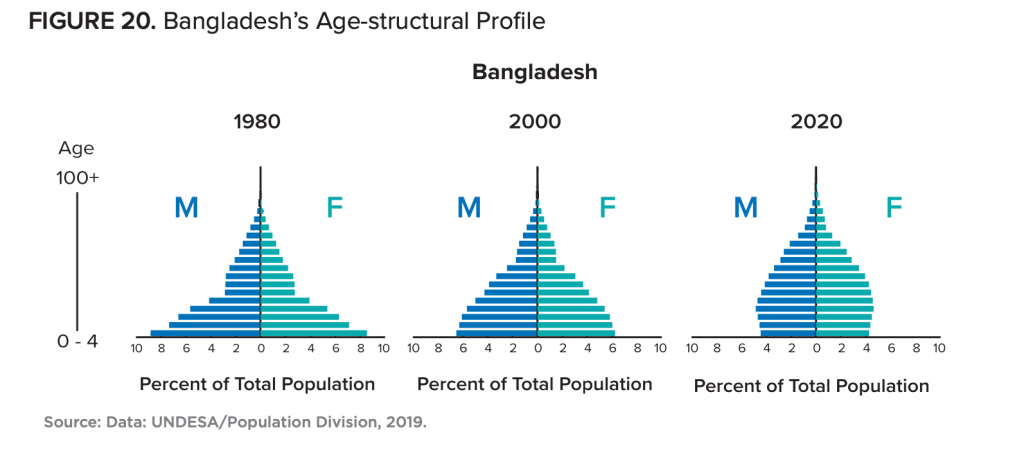

The report also highlights the pathways taken by three countries that politically, programmatically, and without coercion, facilitated relatively rapid fertility transitions and age-structural transformations: Tunisia, Botswana, and Bangladesh. While these states differ geographically, culturally, and economically from the Western Sahelian states, their demographic starting points were similar. Initially, each experienced a broadly pyramidal profile with a median age under twenty years and, in each, the total fertility rate was estimated at between six and seven children per woman. To these, the paper adds a discussion of ongoing programmatic efforts that are influencing the patterns of reproduction in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Rwanda.

Tunisia. This North African country’s rapid journey out of the age-structural transition’s youthful phase was the product of the vision and leadership of Habib Bourguiba, the country’s first president. His Neo-Destour political party legislated a package of pro-women reforms, including laws that compelled parents to send their daughters to school, raised the legal age of marriage, prohibited polygamy, gave women full inheritance rights, made divorce a judicial process, provided decentralized centers of voluntary family planning, mandated that women could work outside the home, opposed the veil, and curtailed the power of local imams.

Botswana. From its inception, professional care and affordability have been key elements of this country’s reproductive health effort. Family planning services, provided free of charge since 1970, were directly integrated into maternal and child health care at all local primary health facilities. Moreover, the country is one of the few in the sub-Saharan region where girls’ secondary-school enrollment rates—now above 90 percent—exceed boys’ rates. While Botswana shared the initial challenge of high rates of adolescent pregnancy and early marriage with Sahelian countries, its history of effective governance and wise use of mineral rents sets Botswana apart from most countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Bangladesh. This country’s remarkable demographic turnaround was brought about by a dedicated health administration that mobilized tens of thousands of community-based health workers and volunteers, teamed up with a local non-governmental organization called Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), and used an infusion of health commodities and funds from foreign donors. Begun in 1975, Bangladesh’s successful donor-funded approach and its country-wide public-health communications program helped trigger demand for other long-term contraception methods (e.g., injectables and implants), countrywide expansion of the village worker program, and formalization of Bangladesh’s public health supply chain.

Programs in East Africa. Applying lessons learned from Asia and Latin America, reproductive health programs in Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, and Rwanda have attained strong support from national leaders, achieved high public profiles, and obtained strong financial commitments from foreign donors. Over the past three decades, greater attention to girls’ educational attainment, organized efforts to augment women’s reproductive rights and increase political participation, and effective public health communications have improved the effectiveness of donor-funded programs for maternal and child health as well as family planning. Significant service delivery and contraceptive acceptance challenges remain in each of these eastern African countries, including high contraceptive-discontinuation rates, and wide gaps in contraceptive use between the lowest-income households and wealthier, urban families.

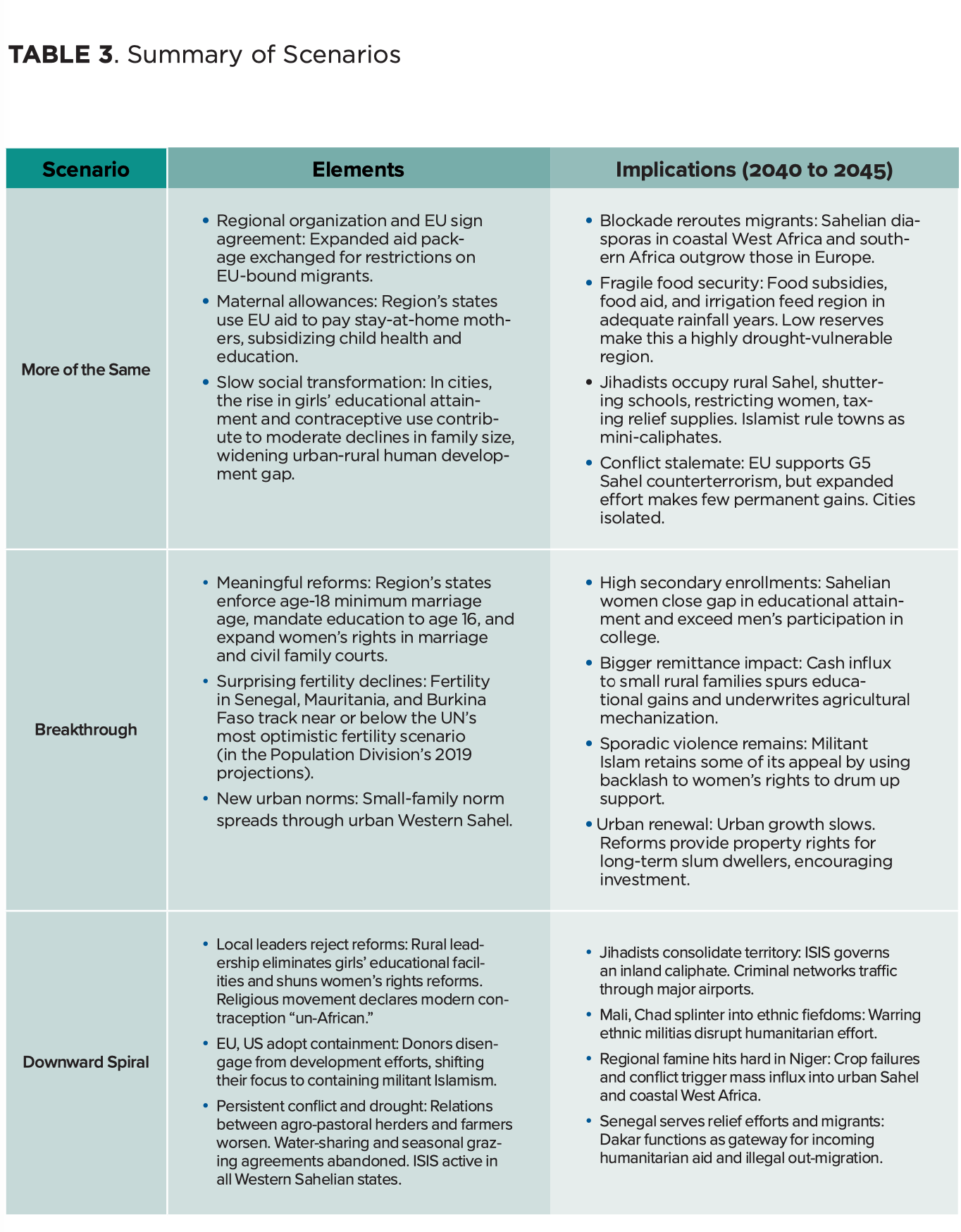

Scenarios

In situations of crisis and uncertainty, scenarios help reduce the scope of options and unveil poorly visible possibilities that could, in the future, catch policy makers unaware. These fictitious futures allow analysts to depart from the most obvious event trajectories and explore other possibilities without having to imagine discontinuities or explain complex chains of events that, throughout history, have led to surprises. For the sake of didactic brevity, we present the following three scenarios under the guise of news dispatches, which shine a light on the situation in the Western Sahel in the early 2040s.

“More of the Same.” In an interregional summit, held in 2043, the European Union (EU) and an organization of Sahelian states agree to a fourth five-year multilateral Migration Convention. The agreement limits and controls the flow of migrants from and through the Sahel in return for a generous increase in the EU’s regional aid package. Girls’ school enrollments continue to rise in the region, and modern contraceptive use increases slowly, spreading from the burgeoning urban areas into smaller cities and towns. However, governments make little serious effort to expand women’s rights or to perturb the patriarchal system that condones adolescent marriages and childbearing. Meanwhile, some Western Sahelian states have instituted cash income supplements for stay-at-home mothers, offering an alternative to women competing in the region’s crowded job market. Meanwhile, Sahelian states continue to pool military resources to contain jihadist groups that remain active across the rural Sahel.

“Breakthrough.” A summit of the expanded group known as G7/Sahel, held in 2043, opens with the rollout of a UN-sponsored report highlighting a reproductive turnaround in several member states in the region and outlines significant progress in others. A local representative of the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) reports on the results of demographic and health surveys indicating that, in both Senegal and Burkina Faso, countrywide total fertility rates have fallen below three children per woman, and that Niger appears to be following on a similar path. Local surveys in several Sahelian cities provide evidence that fertility is near the two-child-per-woman replacement level and that maternal and childhood clinical caseloads as well as school class sizes have dramatically declined. Despite a slowdown in the region’s rate of population increase, ongoing growth due to momentum, increasing temperatures, periodic crop failures, and sporadic jihadist violence, grain imports and food aid remain critical elements of the food-security equation in the Sahel.

“Downward Spiral.” In a UN Security Council session convened in 2043, the Sahel’s special representative calls for international action to address a multifaceted crisis unfolding across the Western Sahel. He describes Somalia-like state failures and territorial infighting among warlords in Mali and Chad, and further outlines deteriorating security conditions across the Hausa-speaking regions of northern Nigeria and Niger, where loosely affiliated jihadist groups have proliferated and, in some cases, gained political control. He also notes that airfields in the Sahel have become the interregional hub for moving contraband, including human trafficking. In his report, the Sahel’s special representative calls the Security Council’s attention to Niger, currently in the throes of a famine on a scale that occurred in the latter half of the twentieth century. This time, Niamey, the capital, is faced with feeding a population nearing sixty million, rather than the 5.2 million of the mid-1970s. Senegal, the region’s only gateway for food aid and other humanitarian assistance, is also the jumping-off place for illegal migration to Europe.

Recommendations

For international aid donors, the report offers a general recommendation: Successful demographic turnarounds over the coming twenty to twenty-five years would feature at least one, and hopefully two, countrywide programmatic success stories, providing exemplars of best practices, a pool of local expertise, and models of community participation that might spread elsewhere. Senegal may be the best candidate to host such a model program. Another focused effort should be launched in an inland state—perhaps Burkina Faso, if its rural areas are pacified. In Niger, Mali, and Chad, the most effective interventions will likely be those that vastly improve urban services and expand a trained cadre of dedicated health workers to deploy in urban peripheries and refugee camps, where demands for education, family planning, and other reproductive services are typically high. In addition to the more general take-aways, the report’s specific recommendations are as follows:

Gain from urbanization. By 2045, nearly half of the region’s growing population is projected to live in urban areas. If services can be mobilized and funded, it will be in these urban centers that young Sahelians receive the vocational and professional education and attain the income-generating employment that could keep many of them from slipping into the illegal or extremist margins of their societies. It is imperative that girls’ education and voluntary family planning—along with other reproductive, maternal, and child health services—are also in place in these expanding cities and towns, and that women gain access to both the private- and public-sector workforce.

Ramp up girls’ education and family planning. Governments in the region should reinvigorate their commitments to increasing levels of girls’ educational attainment and, with the assistance of international donors, vastly increase levels of spending on family planning and other reproductive health services. States should elevate the administrative profile of family planning to a ministerial responsibility and augment its public profile through information campaigns. Education and health administrations should eliminate bureaucratic, traditional, and religious barriers to girls’ school attendance and facilitate easy and affordable access to family planning services for both married as well as single individuals. Methods of delivery that directly bring basic reproductive health services to people in their urban neighborhoods and rural homes—including village health workers and mobile clinics—may prove most effective in Sahelian conditions. At this stage of development, it would be helpful if Sahelian professional societies develop an online library of local success stories that cover girls’ education, family planning, as well as sexual and reproductive health.

Work with respected religious and political leaders, and other public figures; involve and inform men. Exposure to supportive messages from religious leaders who address questions of religious acceptability is generally associated with higher levels of modern contraceptive use. Moreover, recent studies indicate that local programs that inform and involve men and seek the support of local leaders may be the most likely to succeed in the Western Sahel. For decades, health communicators have worked with television and radio producers as well as entertainers, particularly those involved in popular daytime dramas (i.e., soap operas) and talk shows to impart public service messaging concerning maternal and child health, nutrition, HIV/AIDS, family planning, women’s rights, and sexual relationships.

Augment women’s rights. In the Western Sahel, much can be accomplished by protecting girls and women from multiple forms of discrimination and violence, and by expanding their rights in marriage. This effort begins by enforcing current national laws that already prohibit all forms of female genital cutting, that outlaw forced marriages, and prohibit marriage before the age of eighteen years. Once married, the region’s women should deserve the rights to initiate divorce, obtain recourse against violence, and secure custodianship over their children in case of marital separation, divorce, or the death of their spouse. Women should have the right to legal recourse and equal treatment in state-run family courts of law, rather than being limited to the judgments of religious and traditional courts, which have generally failed to protect women and children from physical, psychological, and economic harm. Where political resistance has rolled back legislative efforts to augment women’s rights (as it has been the case in Mali), government support and endorsement of women’s legal, professional, cooperative, and educational societies may offer alternative routes for many Sahelian women to achieve greater autonomy and attain leadership positions.

Bring services to marginalized minorities. Health and education ministries should ensure that significant programmatic efforts in girls’ education, voluntary family planning, and women’s rights be distributed, in some form, among marginalized minorities—no matter how geographically or culturally isolated these minorities might be. Prior experiences in other regions suggest that regional, socioeconomic, ethnic, or caste fertility disparities later develop into hard-to-overcome social and economic inequalities that generate political tensions and exacerbate animosities.

Promote women-centered efforts in all agricultural, economic, and infrastructural development projects. All government, private, and donor-supported projects should contain components that facilitate extending girls’ educational attainment and/or quality of education, improve access to reproductive health services, and promote women’s rights and their economic autonomy. No donor-supported project should facilitate the efforts of governments, political parties, or traditional and religious leaders to impede women’s progress in any sector of development.

Manage resource-related tensions between farming and pastoralism. In a more-populous Western Sahel, the future of agricultural and pastoral livelihoods will depend on the development of groundwater irrigation and intensified agropastoralism (a more deliberate integration of agricultural and grazing uses of land), as well as their relation to urban markets. In this more-populous future, the region’s governments should consider enforcing schemes that restrict absentee rangeland users, protect rangelands from further agricultural encroachment, and help pastoralists deter cattle rustling. Meanwhile, governments in the Western Sahel should continue to develop industries that add value to agricultural and livestock products, promote cooperation between farmers and pastoralists, and develop more efficient transport to urban markets.

Protect development gains with investments in local security. In an environment of rapidly spreading jihadist conflict, geographic pockets of progressive local leadership and popular support for girls’ education and other women-centered programs could become primary targets of militants. Affected communities and their leaders deserve special protection provided by police or anti-terrorist units.

Watch the official launch event

Lire le rapport en français

The Foresight, Strategy, and Risks Initiative (FSR) provides actionable foresight and innovative strategies to a global community of policymakers, business leaders, and citizens.