What will the world be like in 2035? The forecast seems dire. In the four years since Global Trends 2030 was published, the biggest change in the world is the increased risk of major conflict. In 2012, a large-scale US/NATO conflict with Russia or China was close to unthinkable. Now, the post-Cold War security order has broken down, and the consequences are immense, potentially threatening globalization.

“The world certainly faces challenges, and Global Risks 2035, one of the most important documents about our global future written in recent years, describes this darkness in detail…Reading this Atlantic Council Strategy Paper, and the following two in this series which will outline a strategy for the twenty-first century and how best to implement strategic plans, is where all leaders—including our own—should begin.”

Lieutenant General Brent Scowcroft, USAF (ret.)

The report projects that, given the broader geopolitical and technological trends, in the best case, the world is looking at multipolarity with limited multilateralism. There would still exist some cooperation where there was strong interest among the great powers. However, fragmentation could easily slide into open conflict. In that worst case, the multipolarity would evolve into another bipolarity—with China, Russia, and their partners pitted against the United States, Europe, Japan, and other allies. In that scenario, conflict would be almost inevitable.

Authored by Dr. Mathew J. Burrows, director of the Strategic Foresight Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security and the principal drafter the highly influential National Intelligence Council publication Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, the report emphasizes that world leaders and policymakers must understand global risks and take imminent actions to make sure that the world of 2035 is a safe and prosperous one.

Table of contents

Part 2: The breakdown of post-Cold War order

Foreword

To many, we live in dark times. A cursory glance around the world confirms that it is not as safe and prosperous as it could, and perhaps should, be. For the first time in history, a terrorist organization has claimed land as its own sovereign territory. A rising global power threatens its neighbors in theSouth China Sea. A once-great power purposefully destabilizes Europe at the same time the continent struggles with weak economic growth, an historic influx of refugees, and political upheaval. As the world becomes more interconnected, it is evident that leaders in both the public and private sectors have not thought through or planned for all the risks.

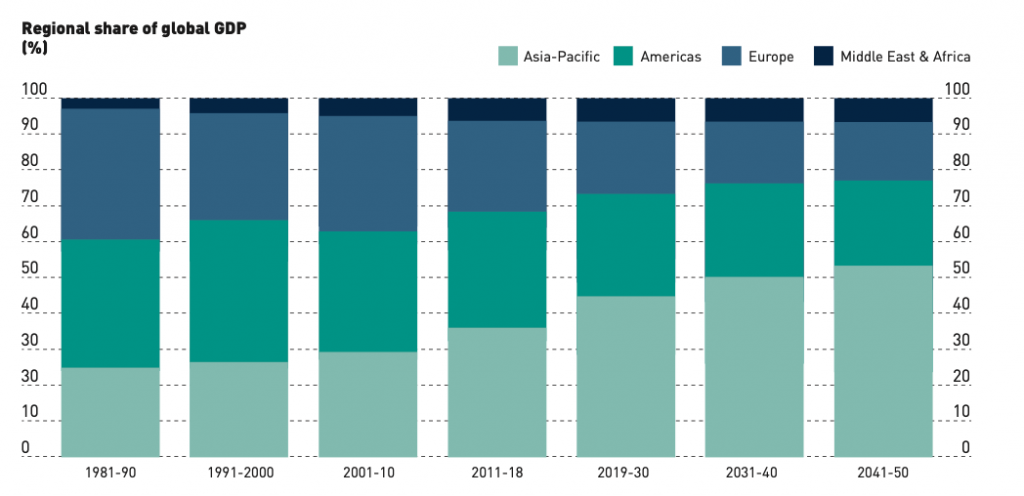

While these are worrisome developments, they conceal the fact that the world is in a better place than it has ever been. Violence continues to decline across the globe as the ages and wages of billions of people increase. Effective governance, while challenged, is prevalent from the state to the municipal level. Technology is empowering a growing global middle class, allowing millions to find opportunity. A power transfer from the West to the East and South will continue to bring many out of poverty and allow those regions to care for their own security. Even in the Middle East, the poster child for instability, a growing private sector and youth bulge may actually prove a positive more so than an impediment to order.

The world certainly faces challenges, and Global Risks 2035, one of the most important documents about our global future written in recent years, describes this darkness in detail. Mat Burrows, the Director of the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Foresight Initiative in the Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security and author of this paper, was optimistic about our collective future when he wrote the National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends 2030 report four years ago. Today, he fears what is coming next and many of his rationales are compelling. Still, there is much light to behold. The world may be full of risks, but there are many opportunities for the United States, along with its allies and partners, to pursue. As the United States looks to weather the storm of the next twenty years, it would do well to prepare for constant change and find ways to harness it for national advantages.

The task for the next president, whoever it might be, will be tougher than for any previous administration. After all, strategy was easier during the Cold War since we knew who our adversary was, what our goals were, and how we would achieve them. Today, the challenges are many, the goals are disparate, and the paths are either politically challenging or completely new for the Western world. Regardless, leaders around the world must understand the global context that they are navigating and how these circumstances help or hinder progress toward desired strategic goals. Reading this Atlantic Council Strategy Paper, and the following two in this series which will outline a strategy for the twenty-first century and how best to implement strategic plans, is where all leaders—including our own—should begin.

Lt. Gen. Brent Scowcroft, USAF (Ret.)

Chairman, International Advisory Board

Atlantic Council

Navigating the future: A strategy for our turbulent world

Strategic foresight: 100-day checklist for the new administration

- Incorporate strategic foresight into decision making in an effort to get ahead of the crisis curve.

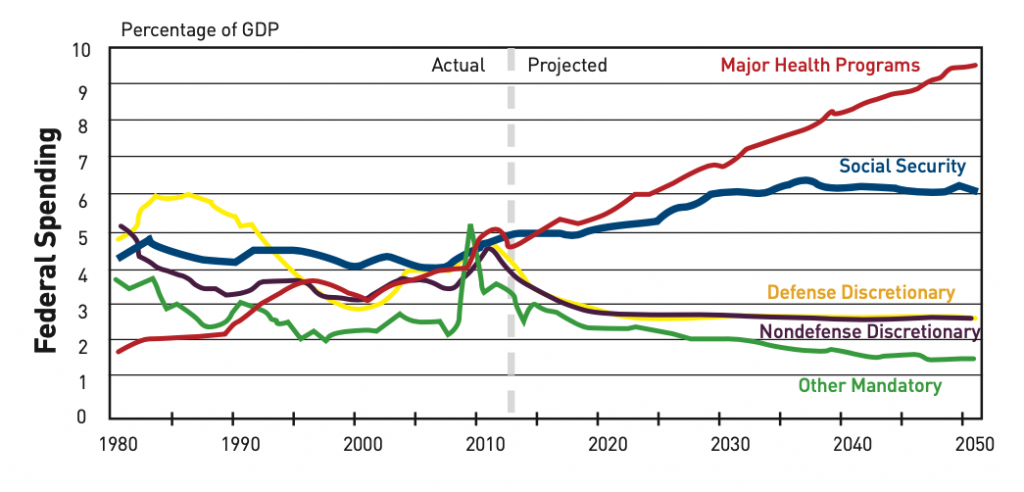

- Undertake entitlement reform. Not putting entitlements on a more solid fiscal foundation willendanger the US’s long term security.

- Treat water security for US allies and partners as a national security priority.

- Put fighting corruption up there with counterterrorism.

- Develop strategies for ensuring new technologies such as geoengineering, drones, synthetic biology, and nanotechnology don’t end up becoming national security threats.

- Stop the slide towards a segmented internet. There is needs to be rules governing offensive cyber.

- Identify new areas of joint cooperation with Russia and China so as to prevent further deteriorationin ties.

- Raise public awareness of rapidly changing world. Consider government funding for area studies programs at US universities.

- Ease barriers to immigration of highly skilled workers.

- Bolster tech training and vocational education.

- Help Saudi Arabia and other Middle East countries develop their economic reform efforts.

Executive summary

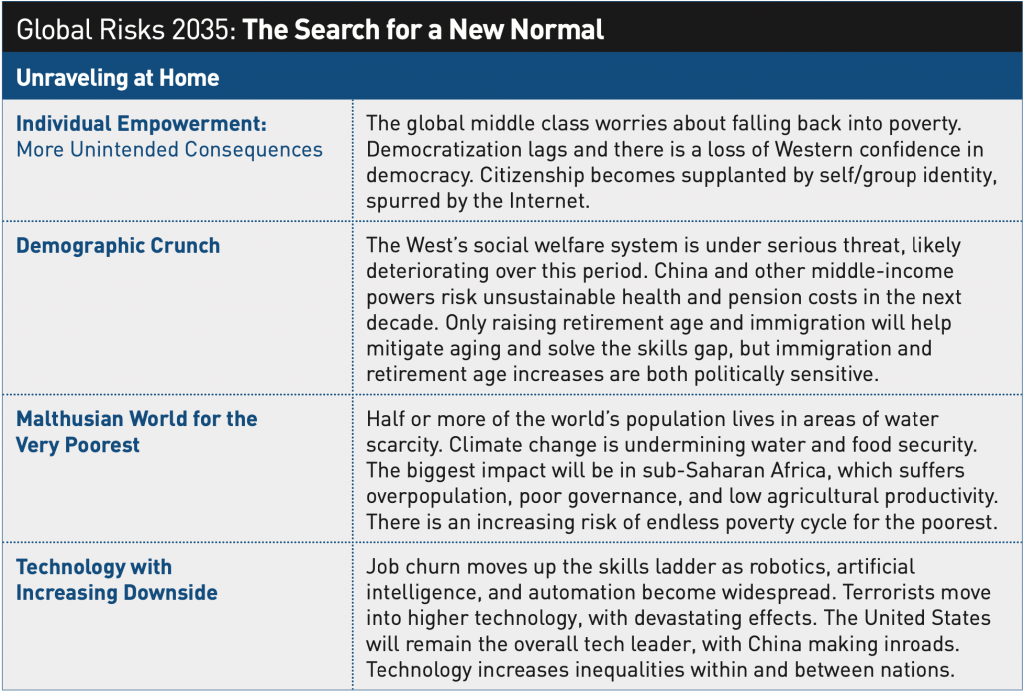

In the four years since Global Trends 2030 was published, the biggest change in the world is the increased risk of major conflict. In 2012, a large-scale US/NATO conflict with Russia or China was close to unthinkable. Now, the post-Cold War security order has broken down, and the consequences are immense, potentially threatening globalization.

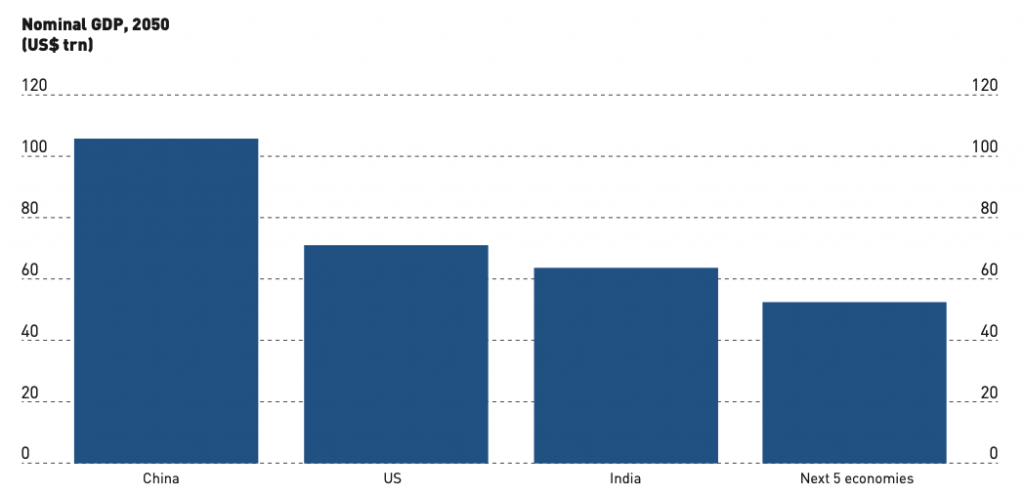

The fracturing of the post-Cold War global system is accompanied by the internal fraying in the political, social, and economic fabric of practically all states. For some time, the Global Trends editions have charted the significant unravelling of societies in the developing world. This unravelling replicates many of the same upheavals associated with the modernization process of any country undergoing rapid change. The spectacular growth of a large global middle class over the last couple of decades is emblematic of the overall success of that modernization process. Never before have so many people been lifted out of extreme poverty and economically empowered, to the point that the future of the middle class now lies in the global East and South. By any calculation, their numbers will dwarf the Western middle classes, even though it will take decades before the per-capita incomes of the global middle class converge with the West’s higher standard of living.

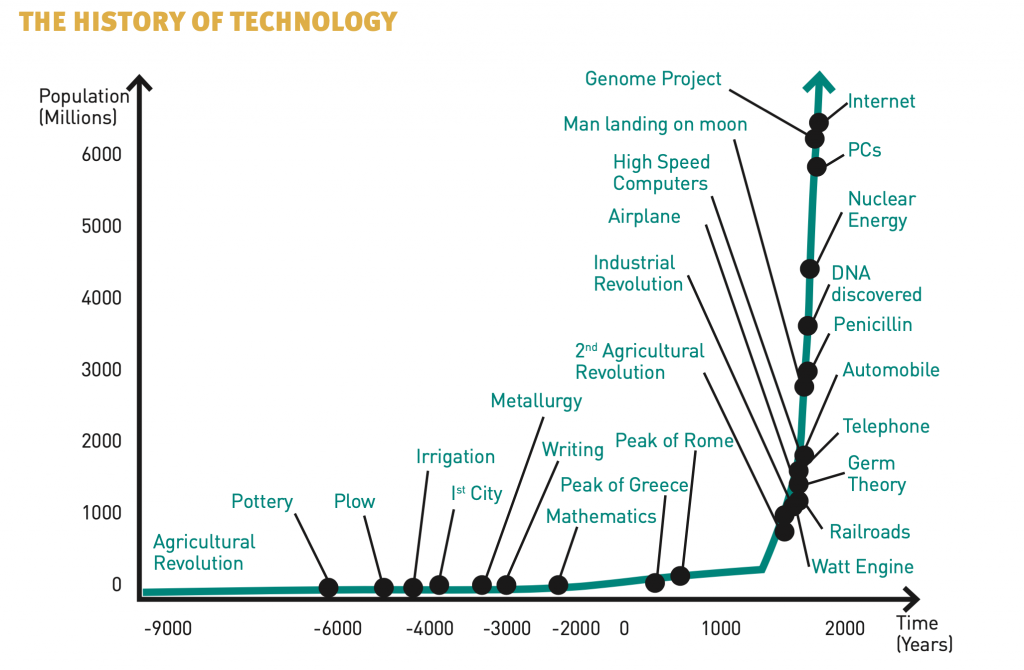

Still, the global middle class is encountering many of the same headwinds affecting the Western middle class. We have learned over the past decade that technology spares no one. The job prospects of Western and global middle classes are already affected, and it is just the beginning. Robotics, artificial intelligence, 3D printing, and automation have the potential to upend both skilled and unskilled occupations. The broad social and economic benefits of the products and services provided by emerging technologies could be immense, but there may be few big winners and many more losers in the short term. This is a far cry from the earlier notion that globalization and technological change would “lift all boats.”

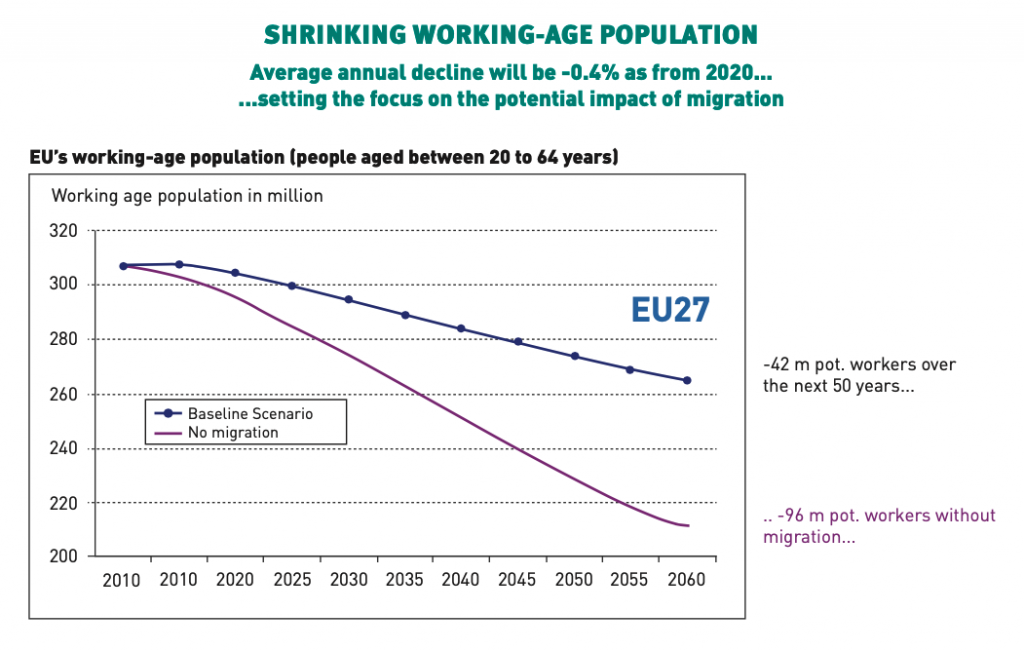

The West is also facing a new demographic challenge that, over time, will affect the developing world. Aging, health, and pension costs are beginning to balloon. It is not clear how Western societies, including the United States, will be able to afford their social-welfare and entitlement programs without squeezing spending on defense, infrastructure, education, and research and development (R&D). Many Western states are facing a drop-off in working-age populations, at a time when these states are often heavily in debt. This fact makes it even more challenging to avoid sacrificing the future for the sake of meeting current social- welfare commitments. Moreover, the stagnant incomes of many members of the Western middle classes are making them unwilling to compromise on what they see as their “entitlements.” The current populist trend in politics looks like it is here for the long haul, undermining the likelihood of decisive action to deal with these challenges.

Developing countries have more time and can learn from the demographic problems facing the advanced economies. But many of the poorest of the developing countries face stiffer, potentially existential, challenges linked to climate change, poor governance, higher incidences of civil conflict, and overpopulation. Climate change will impact everyone in the coming decades, but the poorest areas—sub- Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia—will be hit hardest by rising temperatures and rising

sea levels. Already, the Middle East and North Africa are the driest regions on Earth. Malthusian food and water scarcities could result in the absence of slowing population growth—particularly without good governance and/or peace in many of the areas most affected. This is an avoidable tragedy, except for the fact that the governments and societies do not have the wherewithal to meet the challenge. Richer developing countries, like China and India, will be severely impacted, but have more means to deal with the problem. Unfortunately, the richest countries—such as the United States and European nations—are only beginning to see that the political instability resulting from food and water scarcities cannot be cordoned off. Western security will be profoundly affected by climate insecurity. Syria experienced several years of serious drought before its civil war. Drought was not the sole factor triggering the conflict, but it increased the likelihood of the outbreak. The huge influx of Syrian migrants into Europe in the summer of 2015 should be a vivid reminder that “no man is an island.”

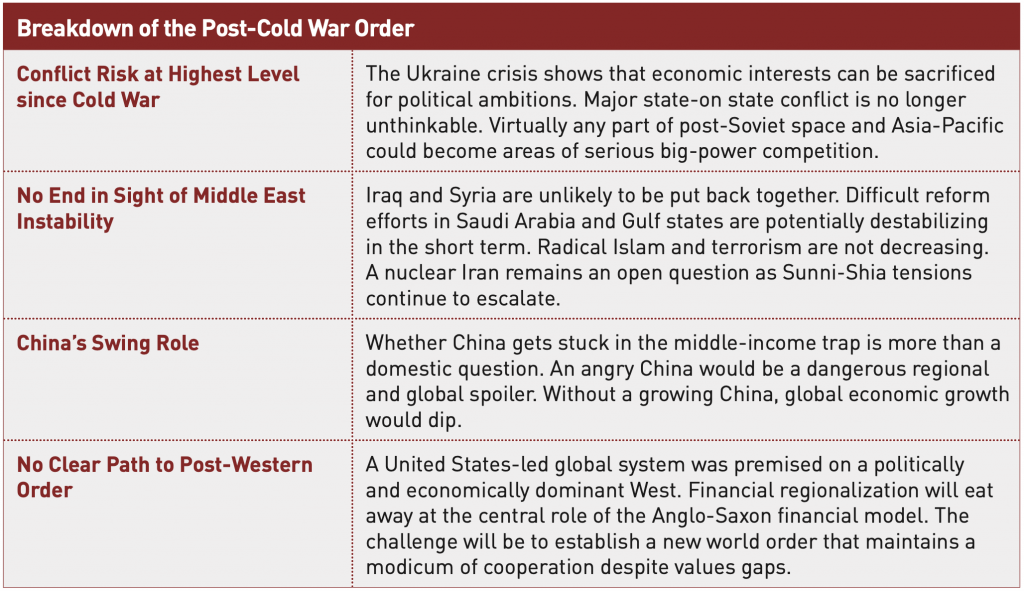

Besides the immense internal unraveling, there are other forces at play in the breakdown of the post-Cold War order. The growing resentment of Western dominance by Russia, China, and other powers has been unappreciated. The crisis in relations between Russia and the West over Ukraine shows the degree to which economic interests and cooperation in international security can be sacrificed for the sake of political, geopolitical, and ideological motives. Virtually any part of the post-Soviet space and surrounding regions, as well as the western part of the Asia-Pacific region and northern part of the Indian Ocean, could become the site of serious competition between the main power centers. The situation is more dangerous than the second half of the Cold War era (mid-1960s to mid-1980s), when tacit “untouchable” geopolitical spheres of influence were very clearly delineated, and other zones were considered not worth the risk of a direct military conflict.

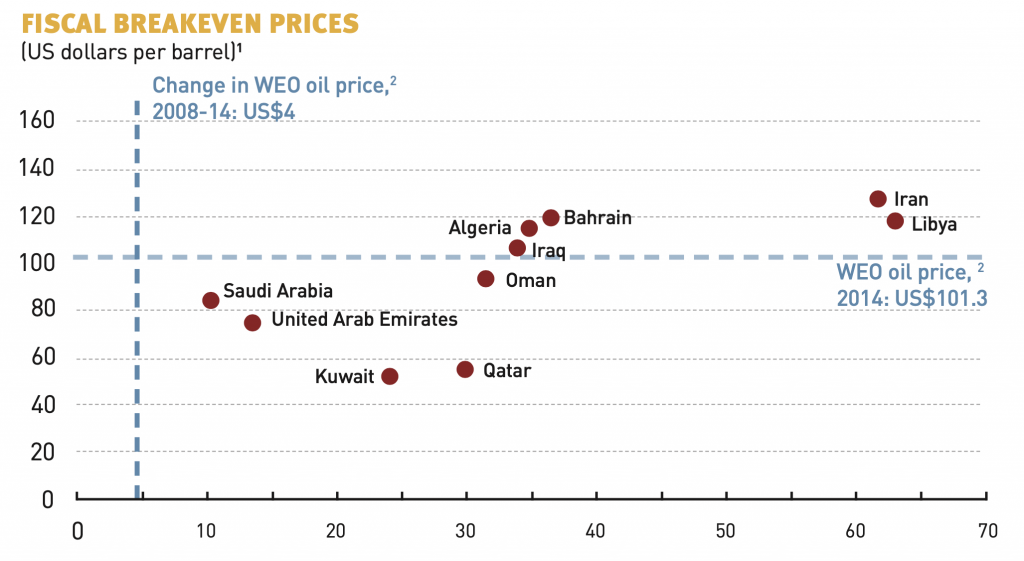

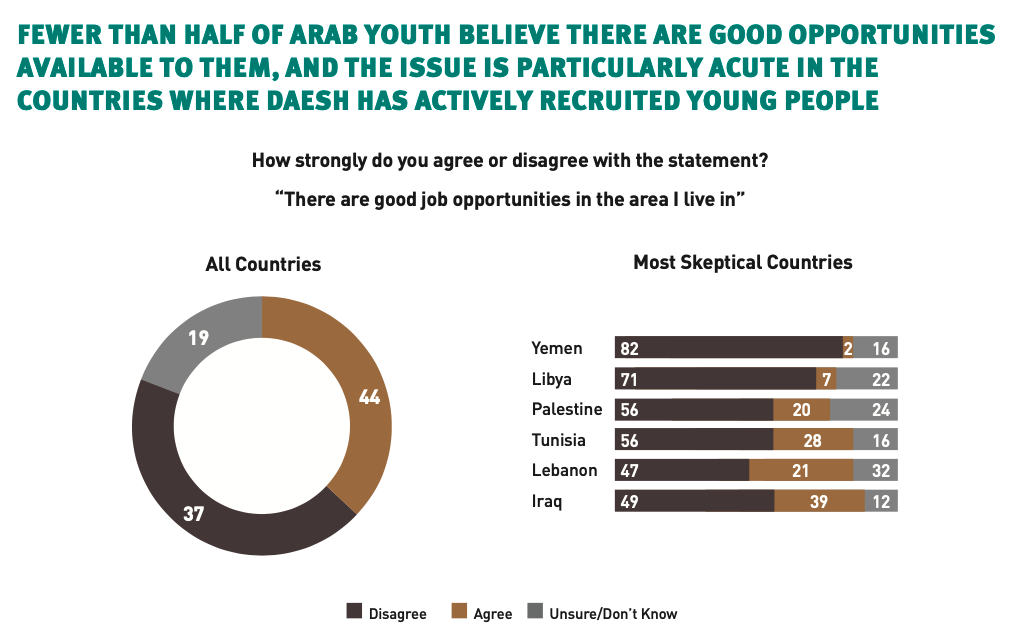

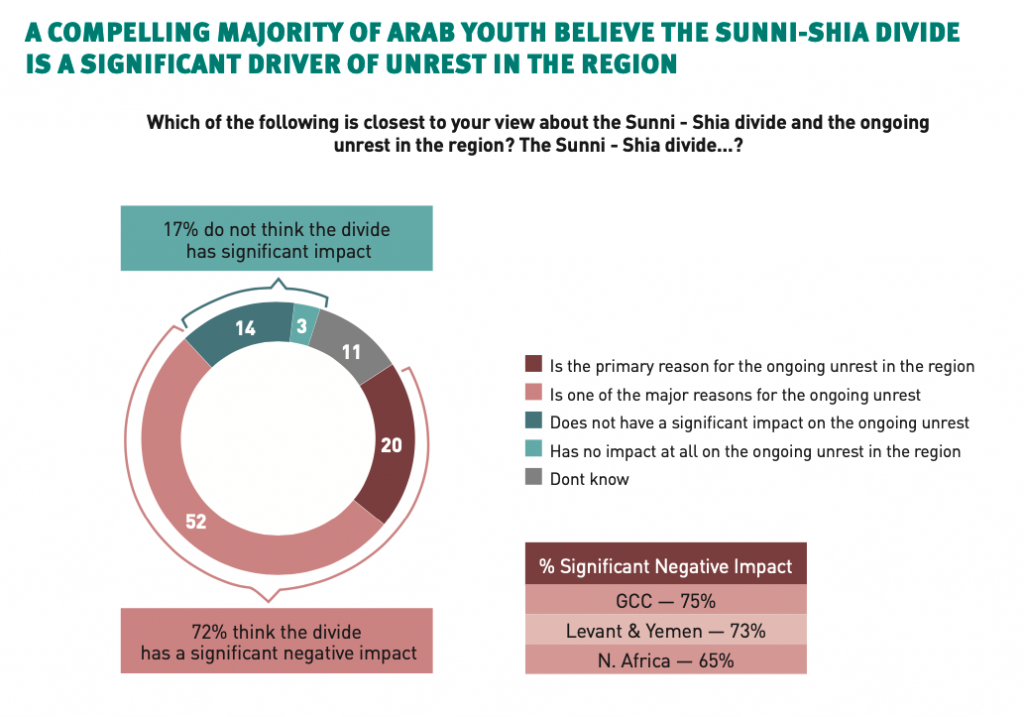

Equally important has been the growth of regionalized conflict, especially in the Middle East, which also threatens global peace and security. There, the decades-long unravelling of the economic and social fabric of countries such as Egypt, Syria, Libya, Yemen, and Iraq has played an instrumental role in the rise of civil strife. For various reasons, governments in those countries could no longer provide the needed economic opportunities for growing youth populations. The increasing importance of ethnic and religious identity has helped ignite internecine conflicts. The end of Tehran’s isolation has raised Arab fears about growing Iranian and Shia influence. The Syrian conflict was internationalized with the participation of actors from around and outside the region. The rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) introduced a new factor—a nonstate group growing so powerful that it has been able to aspire to statehood and, indeed, to the renewal of the old caliphate. The sources of economic and political instability for the region are unlikely to end soon. Civil conflicts tend to last six to nine years, and have a high potential for reigniting. The likely end of high oil prices is a further challenge, forcing Saudi Arabia and other oil producers to find alternative sources of economic growth and state revenue.

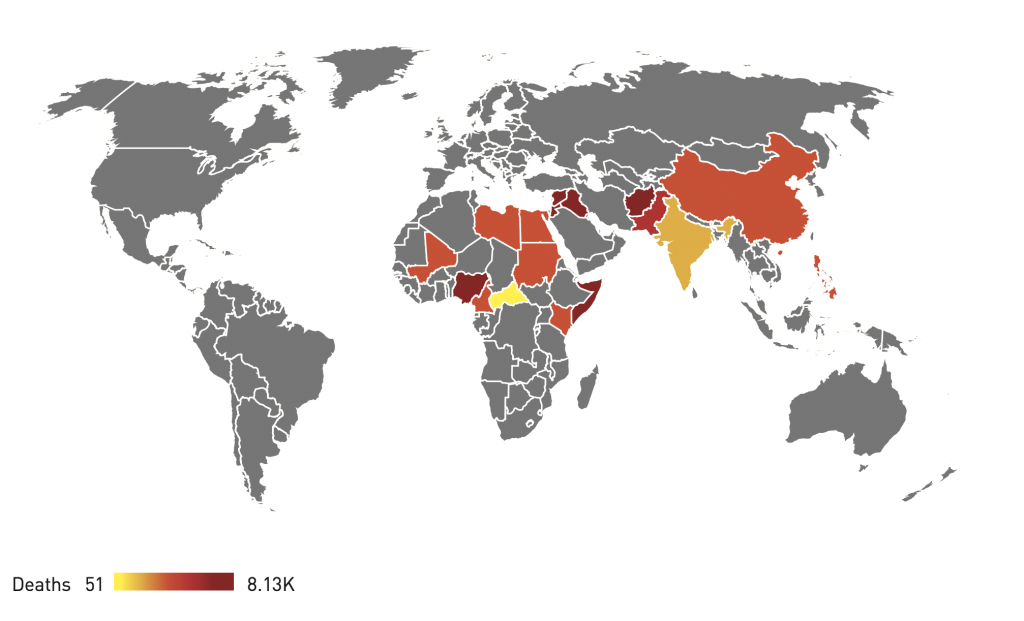

For the rest of the world, an unstable Middle East is a growing threat, exporting terrorism and ethnic and religious division. Other regions where conflict might spread include Central and Southeast Asia, as well as equatorial Africa, where a growing number of countries could be drawn into conflict between Muslim and Christian populations. If major states are unable to act together to stop such wars, they might be drawn into them.

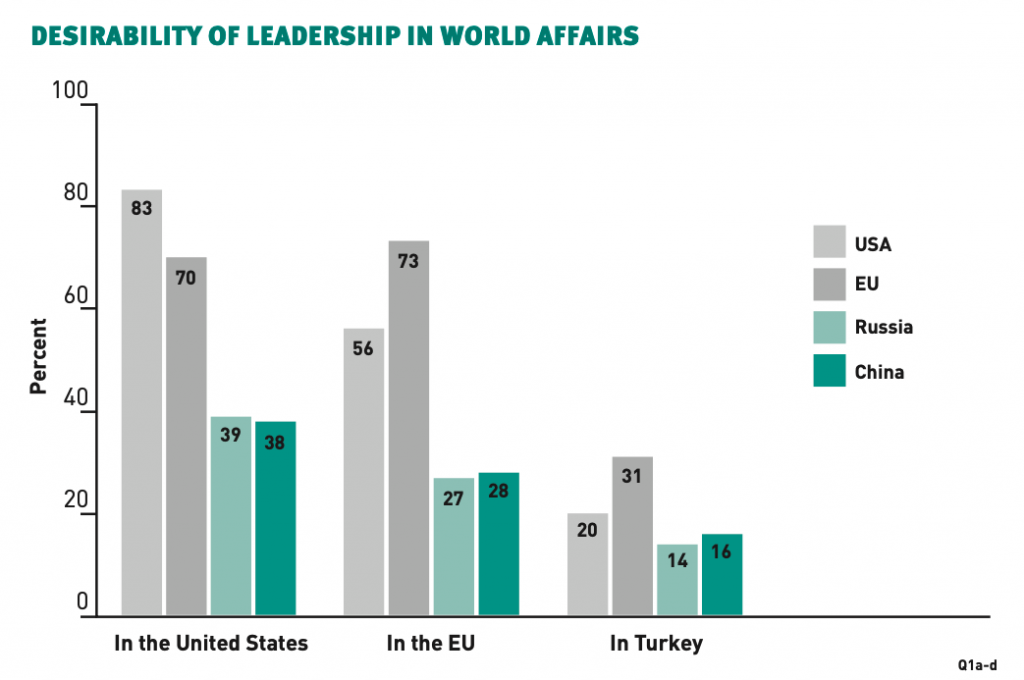

Another threat to international stability comes from within the United States and the West, which are responsible for establishing the current global order. As advanced economies, the United States and its NATO allies are seeing the foundations of their societies begin to buckle under pressure from technological change and more economic competition from the rest of the world. Most US and European citizens have grown up expecting governments to provide economic opportunity, or at least a substantial social safety net. For the first time, a plurality of Americans and Europeans believe their children will not have the opportunities they had. Polling shows that some are even beginning to doubt the merits of democracy. In Europe, discontent has increasingly turned into opposition to the European Union. Western pessimism stands in stark contrast to public sentiment in many parts of the developing world, which is very optimistic about the future. Many Americans say they do not want isolationism, but nevertheless believe the United States can no longer be the world’s policeman and needs to tend to problems at home. A growing number of Americans and Europeans want to close the gates to Middle Eastern and African refugees, even though migrants have been a source of new jobs and entrepreneurship.

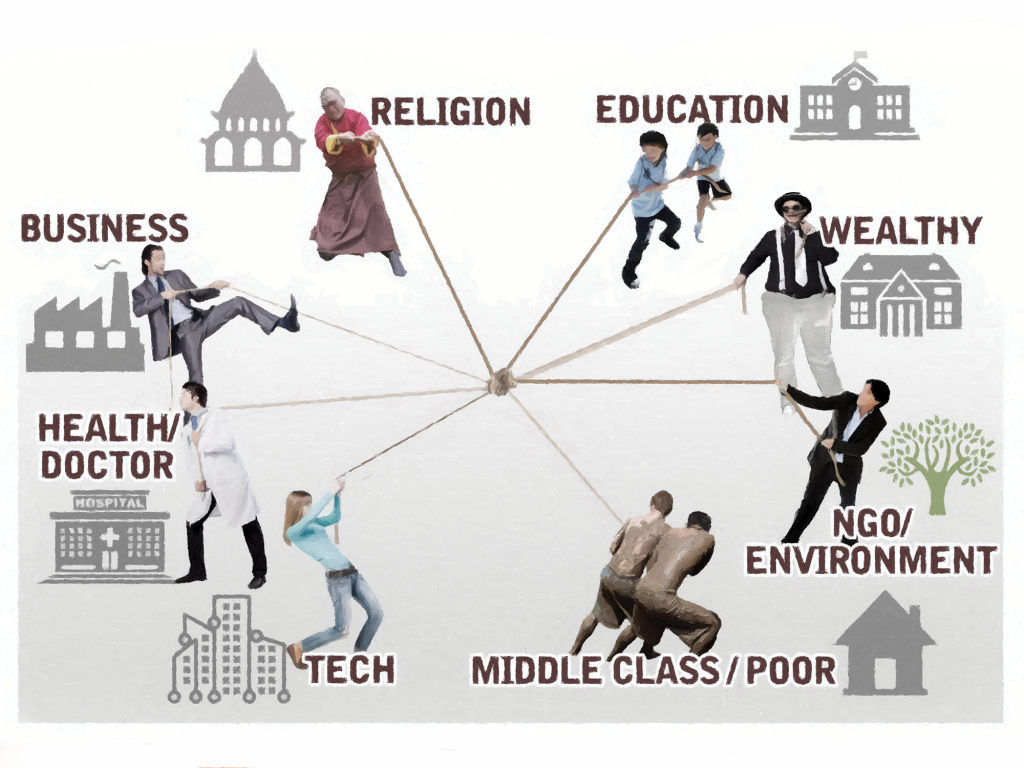

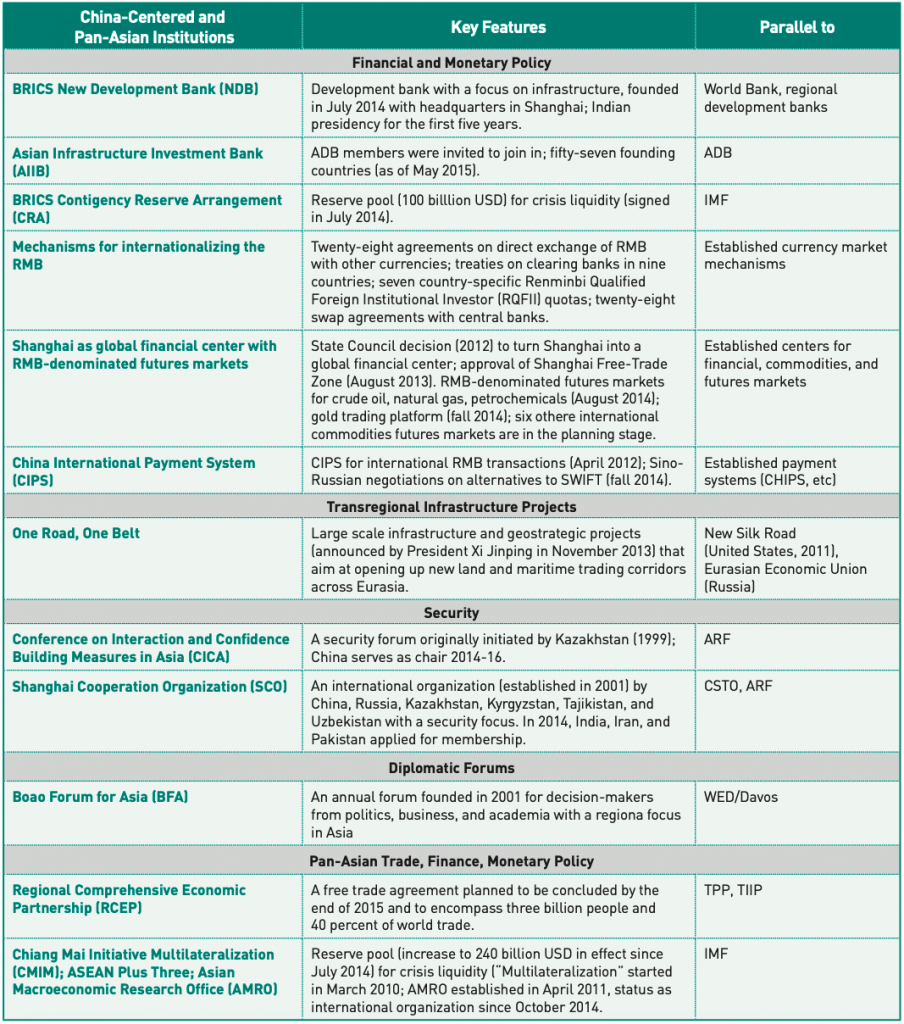

The West’s interrelated crises are coming at a time when Russia, China, Iran, and other powers are questioning the legitimacy and tenets of the West’s international order. The lag between the diffusion of power in the international system and the distribution of power in the structure of multilateral institutions has fostered resentment. Ironically, what appear most in question are Western policies that are falling out of favor with many Western publics—such as humanitarian intervention, regime change, and democracy promotion. China, Russia, and other emerging powers view international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) as agents of Western meddling that threaten their national sovereignty and interests. In recent years, China, particularly, has started to establish a network of parallel regional institutions that provide it with more independence from Western-dominated institutions such as Bretton Woods. While the world is not in a state of anarchy, it is also not primed to take on many of the big challenges, such as state failure, underdevelopment, and civil war.

Besides the tectonic shifts at the geopolitical level, the technology revolutions have changed, and will continue to upend, everyday life for most everyone. The political and social responses to the new technological developments are not as linear as once thought. In the early days of globalization and technological breakthroughs, the thinking was that each would reinforce the other. Two decades later, it is becoming evident that what was once thought inviolable—the World Wide Web—could end up being broken up. China’s firewall is maybe the first indication of that segmentation. There is an economic cost to the increasing fragmentation, but it may not be as high as previously thought.

Given the broader geopolitical and technological trends, in the best case, the world is looking at multipolarity with limited multilateralism. There would still exist some cooperation where there was strong interest among the great powers. However, fragmentation could easily slide into open conflict. In that worst case, the multipolarity would evolve into another bipolarity—with China, Russia, and their partners pitted against the United States, Europe, Japan, and other allies. In that scenario, conflict would be almost inevitable.

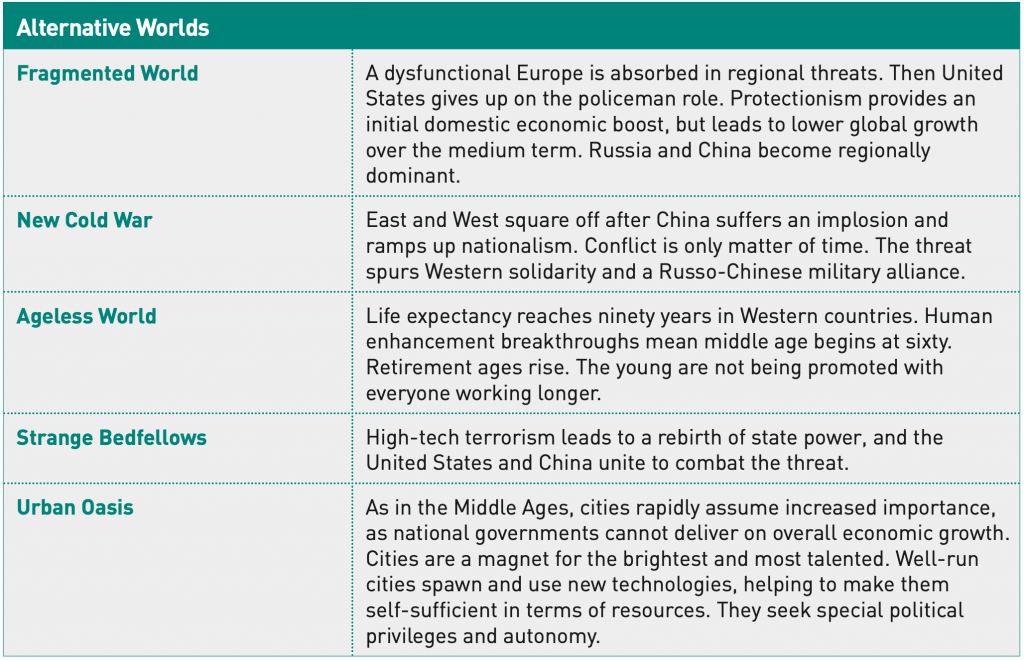

The base-case scenario—here called Fragmented World—linearly projects the current trajectory. Globalization would slow appreciably, but not die. It would assume that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) would not pass, or will be significantly truncated. Protectionist forces would strengthen, but not dominate. There would be little forward movement on free trade, but limited backsliding. The one area in which protectionist forces would prevail is immigration policy. Borders along the EU’s outside perimeter would harden. There would be no repeat of German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s open asylum policy. After two years of negotiations, there would be a soft Brexit deal, allowing the United Kingdom (UK) access to the single market. However, the UK would have to adhere to the EU rules—except those regarding free movement, for which the UK would set its

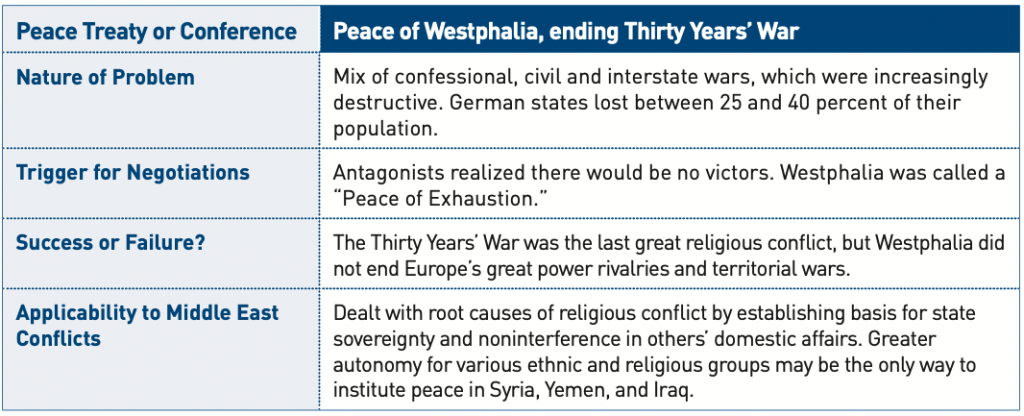

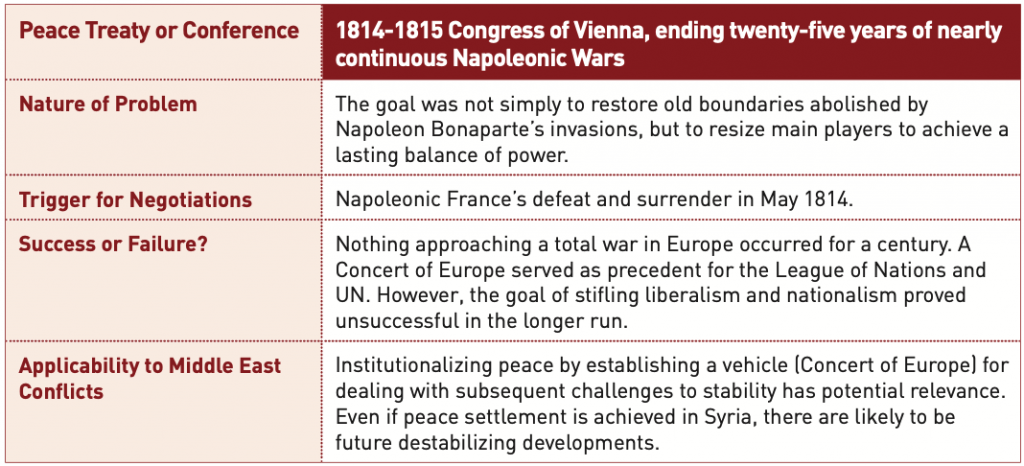

own policies. A harsher settlement would reflect an accelerating fragmentation and fear of breakup in the EU. There would be limited efforts to try to end the Middle East conflicts. Even if a peace settlement is finally reached, Western governments would have difficulty getting public support for marshaling any large-scale peacekeeping efforts. Iraq and Syria would likely remain failing states and relative safe havens for terrorist groups. The conditions would remain for a large-scale war between Sunni and Shia powers. Saudi Arabia would find it more difficult to reform in this lower-growth, less-open economic environment. Global cooperation between the West and the emerging powers would continue on selected issues, such as climate change. Seeing a more inward West, Russia and China might feel less threatened, and their defensiveness could ease. For the Chinese, a less assertive United States on the world stage might give them hope that they could strike a deal with the United States regarding the South China Sea. Over time, as domestic problems are tackled, there may be more appetite in Western and developing states to boost cooperation.

With the growth of inward-looking regional blocs, there is always the risk that Fragmented World would get catapulted into a New Cold War scenario. US isolationism and the protectionism of the 1930s increased distrust and suspicion and laid the groundwork for the outbreak of the Second World War. Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan miscalculated Allied reaction to their aggression. A Russia, China, or Iran that sought its own revisionism with a slowly declining West might come in for a rude awakening. Certain sets of conflicts—China vs. the United States, Russia vs. NATO, or Western and Sunni powers vs. Iran, Russia, and China—would greatly accelerate the breakup into bipolar camps. A United States that slaps high tariffs on Chinese goods, breaks with its EU and NATO partners, and picks a fight with its neighbors over immigration could also trigger a more rapid reversal of globalization and an ending of multilateral cooperation. Nations in any variant of this conflict scenario would wage economic war, if not indulge in more kinetic varieties. Cyberspace would be turned into a key battleground, where states and terrorist groups would seek advantage by taking out key infrastructure in each other’s territory. There would always be the chance that hybrid warfare would escalate into full-scale conventional or nuclear exchange.

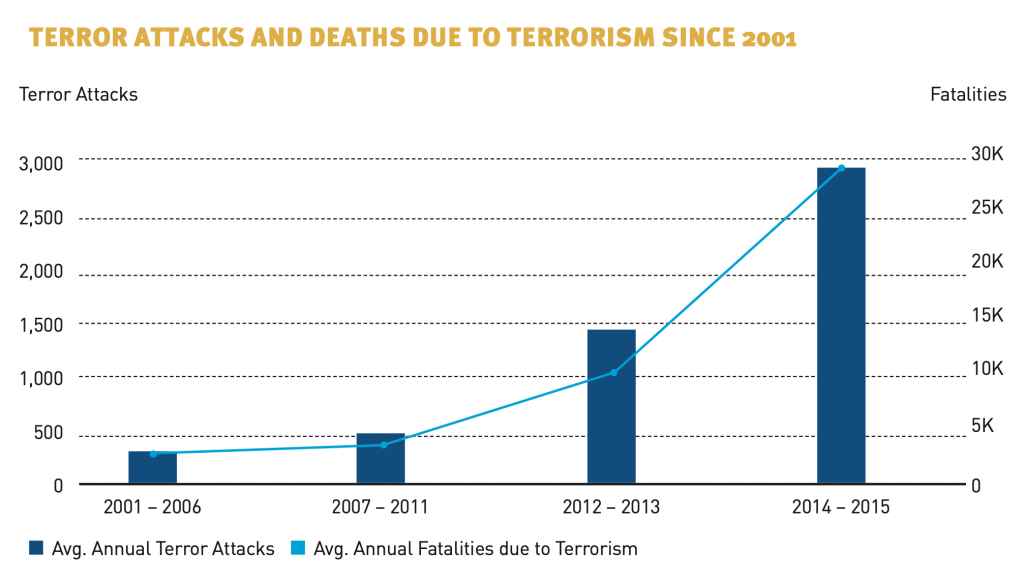

With the rising terrorist capacity for lethality, it is worthwhile to think about the possibility of Strange Bedfellows, in which states are forced to band together to counter the growing power of terrorist and criminal groups that are greatly empowered with high-tech weaponry, such as cyber and biotech. In a high-tech world in which the bar to entry has been lowered and the focus of terrorist groups gradually turns from high-casualty events to disabling critical infrastructure, the fight might turn into one between states and nonstate actors. It would be in all states’ interests to see high-tech capabilities under their control. Suddenly, the world would see state-run labs having monopolies on bio or cyber technology. This would be close to a Hobbesian world in which security, much more than economic growth, becomes the overriding goal for all regimes. While states may still worry about threats from one another, there would be a big incentive for them to cooperate on a selected basis against nonstate targets, mitigating their differences elsewhere.

Each of the above worlds would be colored, if not driven, by two key social and economic trends.

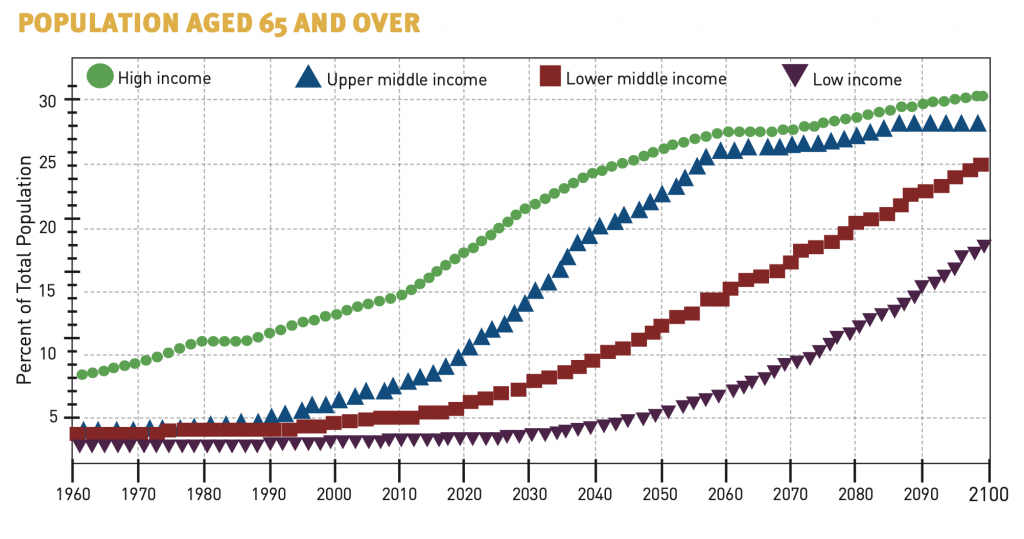

First, as life expectancy reaches ninety years for advanced economies, how to pay for pensions and healthcare programs will increasingly become the state’s focus. Aging and aged societies tend to be conservative ones; a rapidly aging world would favor a West that turns more inward and is hostile to the changes that come with globalization. Brexit, for example, was supported by the older generation. Aging societies are less likely to be interested in going to war, which might prevent the slide into major state- on-state warfare. And all the major powers—the United States, Russia, China, and Europe—will be aging rapidly by the 2020s. There may still be a battleground, but it will be one at home between the young and old. Wealth and income will be concentrated in the older generation. Over time, more intergenerational distribution of wealth may become the norm, in order to avoid an escalation in social tensions and a burst of youthful frustrations.

Growing urbanization may be another feature, adding to the power diffusion in the base scenario, even while moderating any bipolar divisions in the second and third scenarios above. As in previous eras, cities are the focus of technological development and a source of economic growth. Youths are attracted to cities because of the economic opportunities they offer. For as long as cities have been in existence, they have been the places with the most diversity and acceptance of the foreign or “the other.” In the most stressful international environments, major cities would band together in a modern-day Hanseatic League, maintaining levels of cooperation on technology, resource management, and free exchange of people and immigration. Cities may never be able to prevent regions’ downward spirals into conflict, but they could act as the source for regeneration or renaissance. Given that metropolitan cities encompass many more people than ever before, their clout would be greater, and they could be more efficacious in braking the slide into full-scale protectionism or state-on-state conflict.

Importance of leadership

The lack of thinking about and action on repairing the international fabric is itself a concern, given the risks of more open conflict. In her magisterial work on the causes of the First World War—The War That Ended Peace—Margaret MacMillan analyzed how slowly the options for not going to war were eliminated in the fifteen or so years before the outbreak in 1914.1“Margaret MacMillan, The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (New York: Random House, 2013). World War I was not inevitable, but there was little leadership to stop the drift. The assassination in late June 1914 of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s heir— Archduke Franz Ferdinand—shattered the increasingly fragile peace. It would be a pity if, a century later, we had forgotten those lessons.

Introduction

Looking back at what the future was supposed to be

Much of the distress the world has experienced during the last five to ten years has been due to mistaken ideas about what was supposed to happen. With these notions now shaken, it is worthwhile to start by looking back twenty or so years before projecting ahead to 2035. In the 1990s, the United States and the West were enjoying the benefits of the end of the Cold War and the initial burst of globalization. Certainly, the Yugoslav breakup clouded the mid-1990s, but most assumed things were still on track toward a more peaceful, prosperous, and secure future, in which the rest of the world would catch up to and model itself on the West. Four key assumptions shaped the view of the future at that point; all of them now lie in tatters:

- 1. With increasing economic interdependence, the risks of conflict would go down. Instead, the risk of state-on-state conflict has increased, with new conflicts (e.g., Russia-Ukraine-West; China-Vietnam- Philippines-Japan-United States) and old (India-Pakistan and continued turmoil in the Middle East) proving intractable, despite the clear-cut economic benefits of peaceful relations.

- Ideology was dead. The “End of History” hope that all ideological wars had been won by the West was misplaced. Jihadism is worldwide and is proving attractive to marginalized youths, including women. Authoritarianism is staging a comeback, and state capitalism is now an alternative to laissez-faire liberal capitalism. Citizenship is being supplanted by self/group identity.

- The liberal order’s appeal would be enduring, particularly to nonaligned historic powers. Instead, China and Russia have other ideas about how the international system should be run, rejecting post- Westphalia rule sets and harking back to a period when national sovereignty was respected. And they have adherents in the West: Europe’s new right-wing parties want to renationalize European politics and, in the United States, the Tea Party and nativist politicians want to get rid of immigration and downgrade US participation in multilateral institutions. Where does that leave the liberal order?

- Technological growth would be purely beneficial. Silicon Valley’s brain trust has operated under the assumption that, if left alone, technology would solve all of the world’s problems. However, in the short term, automation has eliminated—rather than created—more jobs. Authoritarians have been able to use social media for better citizen surveillance. Revolutions in biotech could be a time bomb if left unaddressed.

There is a cautionary tale here for futurologists. Clearly, it is hard to forecast the future, even if there is more need for better planning than ever before. Instead of one favorable future, all must think about events and developments that can reshape the future away from the linear and positive post-Cold War projections. However, the world in 2035 is not destined to turn out badly, if leaders begin thinking about how to

steer toward more positive outcomes. The original intent of the Global Trends series was to encourage policymakers not to dwell on the current crisis, but to take actions that would help avoid future ones. The innumerable surprises and deceptions over the past decade show the degree to which past planning has been inadequate, pointing to the need to develop better mechanisms for focusing on the medium-to-long term.

Global trends’ track record

The National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends series has never pretended to be a modern-day oracle, but it has held up better than other forecasts—partly because the authors understood that they lived in

a revolutionary age with change, not continuity, as the overall megatrend. The authors were criticized in 2004 for questioning whether the emerging powers would gravitate to the Western liberal order or want to develop their own rules for how the international order should be run. From the policymaker standpoint, it appeared illogical that China—which had benefitted so much from that Western order—would not end up like Japan or South Korea, which had been integrated into the West. Why also should the NIC raise such issues as the relative decline of the United States or Europe? In 2004, when the NIC’s Global Trends 2020 questioned whether the EU could or would be a superpower in 2020, the European Commission quickly dispatched a memo criticizing the report for even raising the issue. Less than fifteen years on, the question seems highly relevant.

Before work was started on Global Trends 2030, two academics, University of California at Berkeley Professor Steve Weber and then-RAND analyst Eli Ratner, were asked to evaluate the previous four editions. The Weber/Ratner verdict was very positive, praising the works for identifying the key drivers of change and praising the regional analysis. The shortfall was in forecasting the rate of change. Even in subsequent editions after Global Trends 2010, the authors underestimated how quickly change was happening. Global Trends 2025 foresaw, for example, the future international system as becoming multipolar, but not as early as the 2010s. The report assumed that China would be, in the mid-2010s, following Deng Xiaoping’s advice of “coolly observe, calmly deal with things, hold your position, hide your capacities, bide your time, accomplish things where possible.”2“Less Biding and Hiding,” The Economist, December 2, 2010, http://www.economist.com/node/17601475. It also assumed that Russia would remain mired in its internal problems, not challenge international rule of law by its annexation of Crimea and become again an active player in the Middle East. Over the longer run, the authors did foresee a breakdown of the international system, warning rather presciently in the 2008 edition that “…we cannot rule out a nineteenth century-like scenario of arms races, territorial expansion, and military rivalries.”

Another key gap was in ideology. This was a recurrent criticism, and one that the authors found difficult to overcome. Certainly, as everyone acknowledged, the world no longer lived in an ideological age like the Cold War, when communism presented a direct challenge to Western market capitalism and democracy. Global Trends 2025 (published in 2008) spent some time delving into state capitalism. The possibility of the return of a caliphate was also addressed, featured as one of the four key scenarios in the Global Trends 2020 volume (published in 2004).

However, it was still difficult to get a fix on the scope and extent of the ideological challenges. Many experts inside and outside the NIC found it hard to imagine that there could be a real challenge to the Western system of market capitalism and democracy. Conservative critics were particularly scathing regarding Global Trends 2025’s forecasts of a relative US decline and of the growing clout of non-Western powers. Even those who acknowledged the emergence of an increasingly non-Western world did not see there would be stiff ideological challenges to the Western model.

On jihadism, there was more acknowledgement in the Global Trends works of its attractiveness and sustainability, rooted in societal struggles over the Middle East’s backwardness, inequalities, and modernization challenges. However, even here, there was perhaps too much optimism about jihadism being eventually vanquished and an assumption that, over time, Western values would prevail. Global Trends 2030, for example, talked about “political pragmatism” trumping “ideology helped by a growing civil society and eventually producing a new cadre of pragmatic, entrepreneurial and social leaders.” This may still happen. However, that report was certainly too optimistic about the immediate aftermath of the Arab Spring—which, with the possible exception of Tunisia, has only led to more authoritarianism in the region.

The approach

Because Global Trends and its methodology is so well-known, this paper will draw on Global Trends 2030’s categorization of megatrends, gamechangers, and scenarios. For the most part, policymakers found that framework useful for helping them think about the future. Where necessary in this study, the author has updated the findings in Global Trends 2030, augmenting them with more recent research and greater understanding of the potential futures out to 2035. But, the author has decided to organize this work differently, given the acceleration of many of the more negative trends. Part I groups together the internal megatrends and potential gamechangers that increase the domestic political, economic, and social dislocations and crises out to 2035. Part II focuses on the megatrends and potential gamechangers that are breaking down the Western-dominated global order. Throughout, this report does not ignore that the current workings of internal and external crises could have long-term positive yields. The world has come to the brink before, and out of it has come order and stability. The title—The Search for a New Normal—is indicative of the author’s view that the world is in a difficult transition, and both positive and negative outcomes are possible. Part III explores where the current megatrends and gamechangers could lead out to 2035. Achieving a new “normal” will be difficult. Centrifugal forces are in ascendancy. Leadership will be needed to prevent a more dangerous slide into conflict, and provide a needed breathing space for societies across the world to work out internal problems and begin to stabilize. As pointed out in Global Trends 2030, a multipolar world is not inherently unstable.

The Global Trends literature has been greatly enriched in recent years as more governmental organizations, businesses, universities, think tanks, and others have begun to study the rapidly changing geopolitical, socioeconomic, and technological landscapes. Since leaving the intelligence community, the author has directed the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Foresight Initiative in the Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security. The initiative has undertaken important research and writing on a number of the trends analyzed in this volume. Other units of the Atlantic Council have also contributed important insights to this study. Several chapters indicate the places where the findings of those researches and reports have been used, in some cases extensively so.

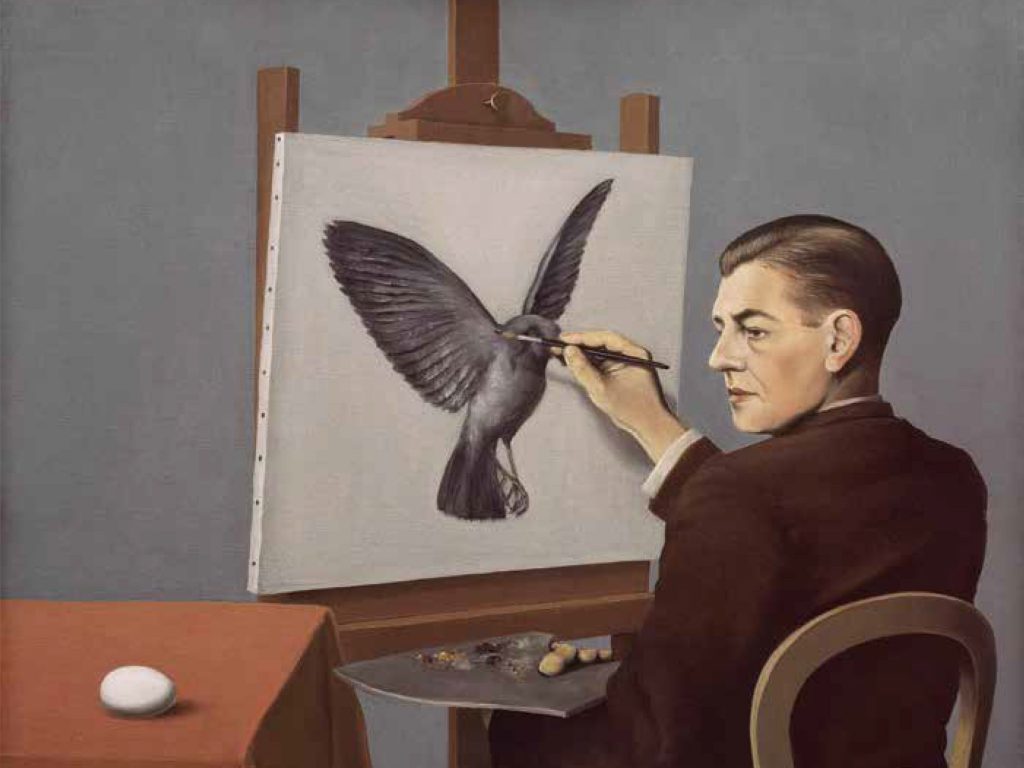

There is no substitute for creative thinking—particularly in depicting alternative futures—and the National Intelligence Council has deliberately developed an “Art of the Future” project to solicit short stories and images about what life will be like in 2035. Some of the entries in those contests will be featured in this publication. (A fuller representation will go on the website.)

The author wants to stress that this volume has not been produced under the auspices of the National Intelligence Council, from which he retired in 2013. As author of the last three Global Trends editions (2004, 2008, 2012), this study uses—as explained above—the methodology and insights of the previous works as a starting point for analyzing the trends and scenarios out to 2035.

Part 1: Unraveling at home

Chapter 1

Individual empowerment with more unintended consequences

The introduction of the “individual empowerment” megatrend was the biggest innovation in Global Trends 2030, and the one that has gained increasing traction. Other Global Trends editions acknowledged the increasing clout of nonstate actors, but the focus—given it was a government publication—was on states. Every previous Global Trends volume led with a discussion of state power, usually about how new powers were rapidly coming onto the geopolitical landscape. In Global Trends 2030, individual empowerment was rooted in a number of underlying subtrends, such as the expanding global middle class, growing educational attainment worldwide with a closing gender gap, an expanding role for information technology, and what was labelled a “more conflicted ideological landscape.” Increasingly, the second- and third-order effects are seen. This tends to reflect the immediate risks more than the longer-range benefits.

Terrorism has spread with more attacks, particularly in the Middle East and Africa. ISIS and al-Qaeda get much of the attention in Western media for their killings of civilians. Boko Haram, however, has displaced one million Nigerians, killing more than 6,300 civilians in 2014, including two thousand people during one day.3Mark Anderson, “Nigeria Suffers Highest Number of Civilian Deaths in African War Zones,” Guardian, January 23, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/jan/23/boko-haram-nigeria-civilian-death-toll-highest-acled-african-war-zones.

Though less violent, the more frequent cyberattacks are also evidence of the capability of individuals and small groups to use new information technologies to do increasing harm. In collaboration with Zurich Insurance Group and the University of Denver’s Pardee Center, the Atlantic Council recently published a study showing the eye-popping consequences of increasing cybercrime, mostly from nonstate groups and individuals.4Atlantic Council, Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures, and Zurich, Risk Nexus: Overcome by Cyber Risks? Economic Benefits and Cost of Alternate Cyber Futures, (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2015), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/images/publications/risk-nexus-september-2015-overcome-by-cyber-risks.pdf. For advanced economies, the costs of protecting against cyberattacks have begun to outweigh cyber benefits.5Ibid. Although states such as the United States, Russia, China, and European nations have the ability to do even more harm, terrorist networks are becoming more tech savvy and may soon be able to cause large-scale harm.

An increasingly frustrated middle class

There is no doubt that the rise of the global middle class is a story of epic proportions, contributing greatly to individual empowerment. More and more individuals have the ability to realize their potential, no longer trapped in a day-to-day struggle to survive. The world is on track eliminate most extreme poverty in several decades—a historic achievement in view of the fact that, for much of human history, the vast majority of the world’s population was poor. However, the emerging global middle class is waking up to a new reality of lowered expectations, if not frustration. In 2015, the Pew Research Center published a study that saw

the emergence of a truly global middle class as “still more promise than reality.” The big gains were concentrated in China, South America, and Eastern Europe, with China accounting for more than half the additional middle-class population—203 million—between 2001 and 2011. While the global middle-income population doubled in just a decade, the biggest gains were made by those who had moved from poor to low-income level (defined as $2-10 per day). The low-income population increased from 2.7 billion to 3.4 billion. The share of poor diminished from 29 percent to 15 percent, again all in a decade.6Rakesh Kochhar, “6 Key Takeaways About the World’s Emerging Middle Class,” Pew Research Center Fact Tank (blog), July 8, 2015, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/07/08/6-key-takeaways-about-the-worlds-emerging-middle-class/.

Indeed, the biggest fear for the newly emerged middle class is falling back into poverty. One Kenyan official told the author during the writing of Global Trends 2030, “The middle class is still really close to the lower class. They are vulnerable and prone to go back to the poverty level.” One recent economic study estimated that 39 percent of the total population in Latin America is vulnerable; they could see their newly found middle-class status taken away from them as economic growth ebbs in coming years.7Michael Penfold and Harold Trinkunas, “Prospects for Latin America’s Middle Class After the Commodity Boom,” Brookings, February 10, 2015, http://www.brookings.edu/research/articles/2015/02/10-latin-america-middle-class-prospects.

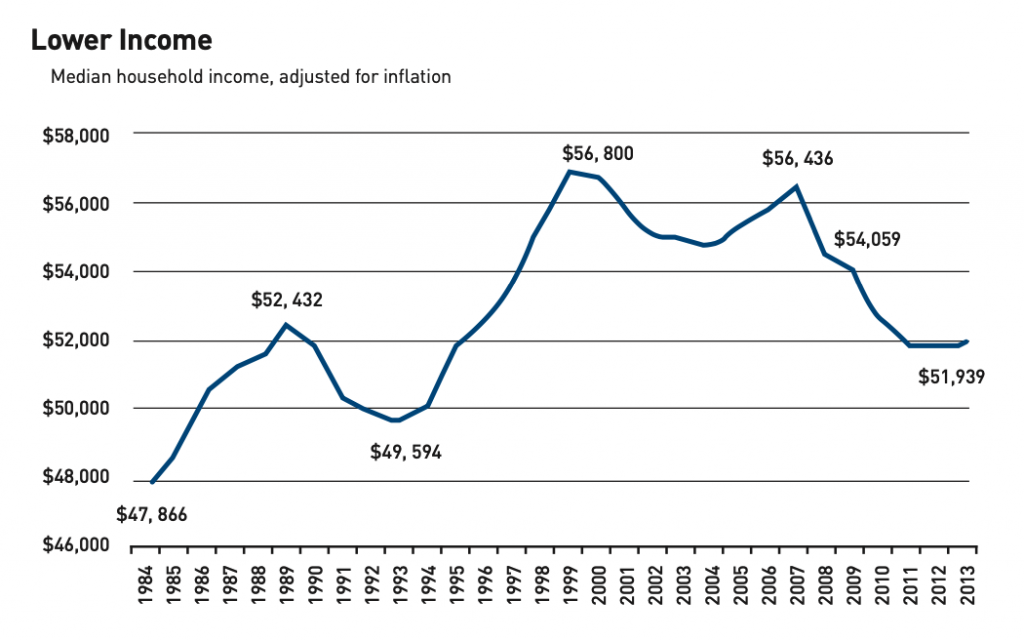

Western middle classes are also frustrated. They have seen their household incomes stagnate or decline as there is increasing competition from new globalized labor markets in the developing world. The 2008 financial crisis accelerated the sense of decline. American adults are now as pessimistic as their European counterparts about their children’s future. The technological revolution is a new question mark, increasing job insecurity for the middle classes in both the advanced and developing world. (See chapter 4 for more on the impacts of technological revolution.)

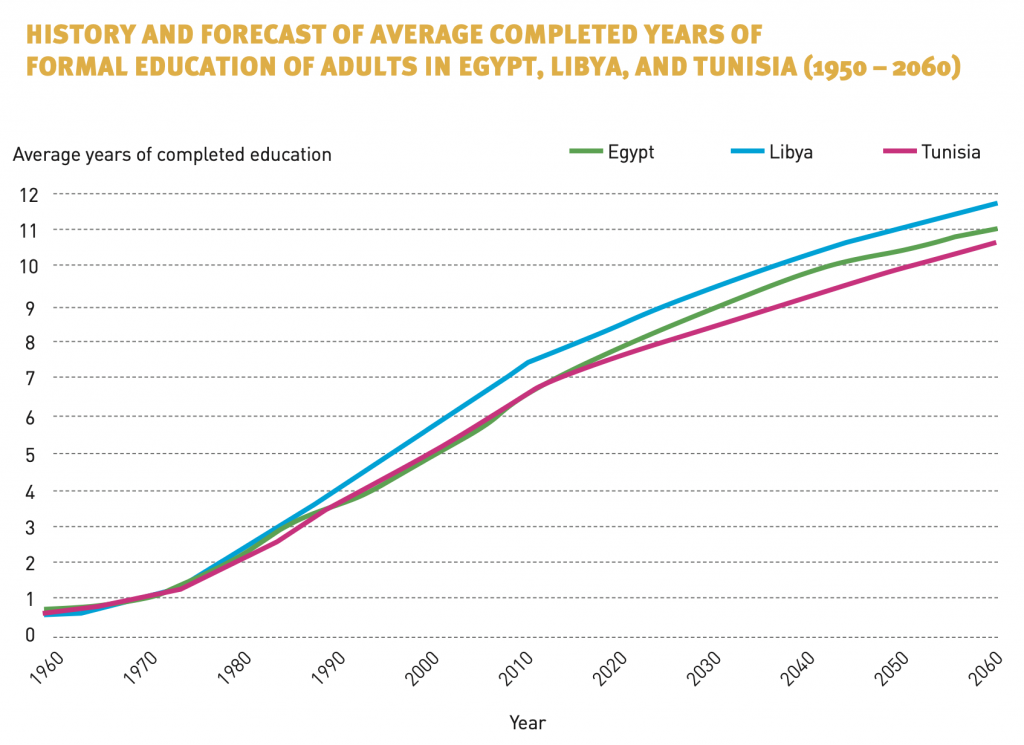

The increasing levels of educational attainment are perhaps the most positive element of individual empowerment, which has long-term positive implications. The progress of the developing world toward convergence with the advanced world bears emphasis. “In 1960, the relative distance between the region with the highest average education years and the region with the lowest was a ratio of over 7-to-1 for North America and West Europe compared to the Arab State. Already in 2000, the greatest distance was a ratio of 4-to-1 for North America and Western Europe compared to sub-Saharan Africa.”8Janet R. Dickson, Barry B. Hughes, and Mohammed T. Irfan, Advancing Global Education: Patterns of Potential Human Progress (New Delhi: Oxford University Press India, 2010), p. 24. Projections for the Middle East and North Africa state that the average years of completed formal education will rise from 7.1 to more than 8.7 years by 2030.9Mathew Burrows, Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds (Washington, DC: National Intelligence Council, 2012), p. 11, https://www.dni.gov/index.php/about/organization/global-trends-2030 Moreover, the level for women in that region could rise from five to seven years.10Ibid.

The highly skilled, wherever they come from, are already in demand—and will be in even more demand in the future. For developing states, the challenge will be to avoid brain drain. More and more students are leaving to get a better education at higher levels. Offering a quality education at home is likely to become a priority if developing states want to keep the “best and the brightest.” Asians have taken this message on board; Asian universities are increasingly showing up in the rankings of the top two hundred universities in the world. However, other regions—Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East—are only slowly improving their quality of, and access to, higher education.

Even when they have graduate degrees, including PhDs, some students cannot find relevant employment at home. In many Middle Eastern countries, higher educational attainment surprisingly correlates with rising joblessness. Some of this unemployment is due to women not being encouraged to join the workforce; the new Saudi reform effort—Vision 2030—seeks to increase women’s participation in the economy. Educational systems in the Middle East and elsewhere have also struggled to deliver graduates with the skills necessary for finding productive jobs. In Saudi Arabia, few private employers want to hire Saudi graduates, complaining that they are unprepared and lack modern skills and a strong work ethic.

Source: Historical data from Barro and Lee 2010; forecast from IFs Version 6.68 Base Cse. IFs database variation is EdYearsAge 25, and forecast variable is EDYRSAG25.

Lagging democracy, too

Besides the socioeconomic benefits, rising educational attainment has historically been—along with rising household incomes—a driver of democratic change. While it is difficult to forecast the precise point at which rising incomes and educational level bring about democratic change, there is a strong correlation over time. Education and income growth also have a “strong relationship with governance quality and especially government effectiveness.”11Ibid. Education is also strongly correlated with corruption reduction.12Ibid.

The problem has been to identify a particular date when education attainment and higher income levels trigger rapid democratization. Global Trends 2030 suggested increasing democracy might be closer, with per-capita income levels reaching purchasing power parity (PPP) of $12,000 in emerging middle-income countries, such as China. However, it also said that the “rise of middle classes has led to populism and dictatorship” on the way to greater democracy.

The democratic slippage has not been as great as some democracy activists have made out. The majority of countries in the world profess to be democracies. It is the most democratic age in human history, without question. The number of authoritarians has decreased from what it was only a few decades ago, although those remaining are more resilient, at least for the moment.

Historically, democratic progress has come in bursts or waves, as the late Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington so brilliantly analyzed. What distinguishes the current moment is the number of semi-democracies or “anocracies.” The Polity IV data series—which measures along a 20-point scale of government behavior, with autocracy below 5 and democracy above 15—currently lists about fifty countries falling into the awkward stage. The greatest number of these so-called anocracies are in sub- Saharan Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. Anocracies are unstable and transitory, with “over 50 percent experiencing a major regime change within 5 years and over 70 percent within 10 years… Anocracies are about 3 times more susceptible to autocratic backsliding than full democracies” and about four times more likely than democracies to experience coup plots.13Monty G. Marshall and Benjamin R. Cole, Global Report 2014: Conflict, Governance, and State Fragility (Vienna, Va: Center for Systemic Peace, 2014), p.24, http://www.systemicpeace.org/vlibrary/GlobalReport2014.pdf. They are also more vulnerable to outbreaks of armed societal conflict.

Maybe because there was such a push toward democratization in the wake of Cold War’s end and the fall of communism, the transition periods for anocracies or semi-democracies to mature into full democracies has been lengthening, particularly for those countries with little previous experience with democratic governance.14Ibid. In the decade following the end of the Cold War (1990-99), there were approximately 3.2 democratic transitions per year. From 2000-12, however, that number fell to just 1.8 per year.

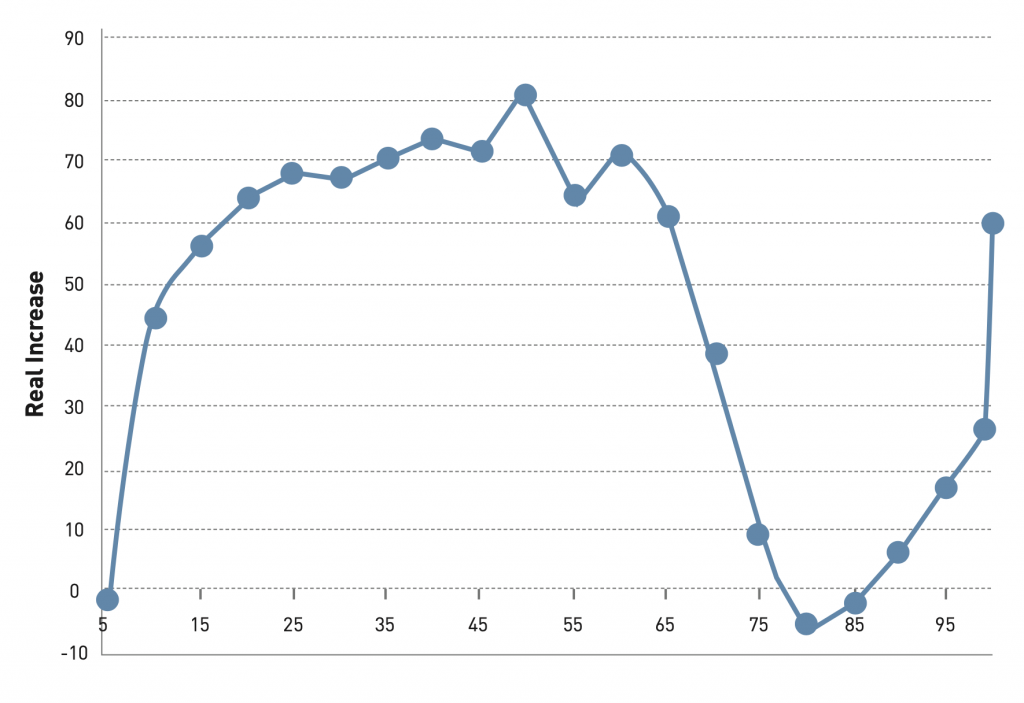

Who benefitted the most from globalization?

Winners and losers: Change in real income between 1988 and 2008 at various percentiles of global income distribution (calculated in 2005 international dollars)

Source: Branko Milanovic, Global Income Inequality by the Numbers: In History and Now (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2012), http://www-wds.worldbank.org/externaldefault/WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2012/11/06/000158349_20121106085546/Rendered/PDF/wps6259.pdf.

Winners: Certainly, this graphic shows that the top-fifth percentile has done very well, seeing incomes increase by up to 60 percent in the 1988-2008 period. But, it also shows that other income groups have done well. According to Branko Milanovic, “The bottom third, with the exception of the very poorest, became significantly better and many of (the) people there escaped absolute poverty.” The middle third also greatly benefitted, by approximately 3 percent per capita annually. All in all, the change in global income was huge: “It was probably the profoundest global reshuffle of people’s economic positions since the Industrial Revolution.” This combined group that escaped poverty are those known today as the global middle class.

Losers: Besides those in extreme poverty who did not do well, there are other losers. The group below the top 5 percent, in the next 20-30 percentile, gained very little or saw stagnant incomes. These big losers are mostly made up of the US and European middle classes.

“When asked by the World Values Survey to rate how democratically their country is being governed on a 10-point scale, a third of Americans now tend toward the end (of the spectrum)—‘not at all democratic.’”15Roberto Foa and Yascha Mounk, “Across the Globe, a Growing Disillusionment with Democracy,” New York Times, September 15, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/15/opinion/across-the-globe-a-growing-disillusionment-with-democracy.html?_r=0.

Since the early 1990s, these researchers found that “votes for populists have soared in most major Western democracies, whether the National Front in France or the People’s Party in Denmark.”16Ibid. The rise of populist, nationalist, and extremist far-right and far-left parties and groups recalls the 1920s and 1930s, when many Western intellectuals and other groups were attracted to totalitarianism and fascism in the wake of the post-World War I political revolutions and accompanying economic crises. Pew Research surveys have also documented the historic decline in trust in government over recent years; the most recent survey showed that trust is “mired near record lows.”17Pew Research Center, “Beyond Red vs Blue: The Political Typology: Section 2: Views of the Nation, the Constitution and Government,” June 26, 2014, http://www.people-press.org/2014/06/26/section-2-views-of-the-nation-the-constitution-and-government/.

Meanwhile, authoritarianism is no longer equated with economic backwardness. Among the poorest countries, only Eritrea is an autocracy. China is the big exception, experiencing three decades of unbroken high economic growth that is only now slowing, after it has become the biggest economic power according to PPP measures. China—whose authoritarian regime faces a weak opposition—is now slated to pass the threshold of $15,000 per capita PPP, which some scholars assumed would be a trigger for democratization. Moreover, some of the highest per-capita incomes in the world are in countries ruled by authoritarians, particularly in the Persian Gulf. Authoritarian regimes in oil-rich countries have historically been able to resist democratization pressures, partly because of generous social-welfare programs. The existence of a number of economically successful authoritarian states undercuts the argument that democracy is critical to economic modernization. Eminent scholars like Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson have found evidence that oligarchies are more conducive than full-scale democracy to economic modernization—at least in the “medium run”—because they are apt to create environments favoring entrepreneurs with low taxation. Only later do oligarchies create problems by erecting entry barriers to protect current economic incumbents.

Authoritarians may be getting smarter, too

Numerous scholars, as well as this report’s own analysis, point to how authoritarians increasingly understand ways to manipulate democratic processes and institutions—such as elections, parties, and legislatures—for their purposes. They also turned the tables on social media. “With few exceptions, social-media fueled challenges to authoritarian regimes have faltered.”18See Zeynep Tufekci’s article, “Authoritarian Use of Social Media,” in Mathew Burrows and Maria Stephan, Is Authoritarianism Staging a Comeback? (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2015), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/books/is-authoritarianism-staging-a-comeback. (This is also true in the case of protests in more democratic countries, such as the Occupy movement or the M15 anti-austerity protests in Europe.) While China has the resources to censor and block politically sensitive material, less resource-rich authoritarian regimes, like Russia, or authoritarian-leaning ones, like Turkey, rely on self-censorship. Media-owning tycoons in those countries generally have other business interests, which make them “beholden to the government’s patronage or good graces.”19Ibid. Media bosses routinely fire journalists for crossing the government’s lines. Those media outlets that do cross swords end up being hit with huge and spurious tax bills that can put them out of business.20Ibid.

Authoritarians use national sovereignty and the threat of instability to contest any universal legal right by outside groups to assist democratic activists. Russian and Chinese government spokespersons point to the widespread turmoil and humanitarian tragedies caused by US and Western intervention in Libya and Iraq to oust the Muammar Gaddafi and Saddam Hussain regimes. In their minds, Western support and encouragement to democratic activists in Egypt, Syria, and Yemen only further destabilized the region. Authoritarian governments have been very effective in using images of disorder and humanitarian disaster to “feed anti-Western narratives, discredit local activists and opposition leaders” and “justify increased harassment of opposition groups.”21Andrea Kendall-Taylor, Changing Authoritarian Dynamics and the Limits of Traditional Engagement: A Case for A Legitimacy Narrative, unpublished paper.

It is important, however, not to see current authoritarians as ten feet tall. Authoritarians have grown more media savvy, for example, because they are conscious that the proportion of autocrats being ousted by public revolt has been on the rise. This is a shift from an earlier pattern, in which the ouster was an inside job—a coup d’etat—that resulted from divisions within the elite. Authoritarians are also conscious that they live in a democratic age, and find it necessary to adopt many democratic forms and processes, even if those are gutted to suit their advantages.

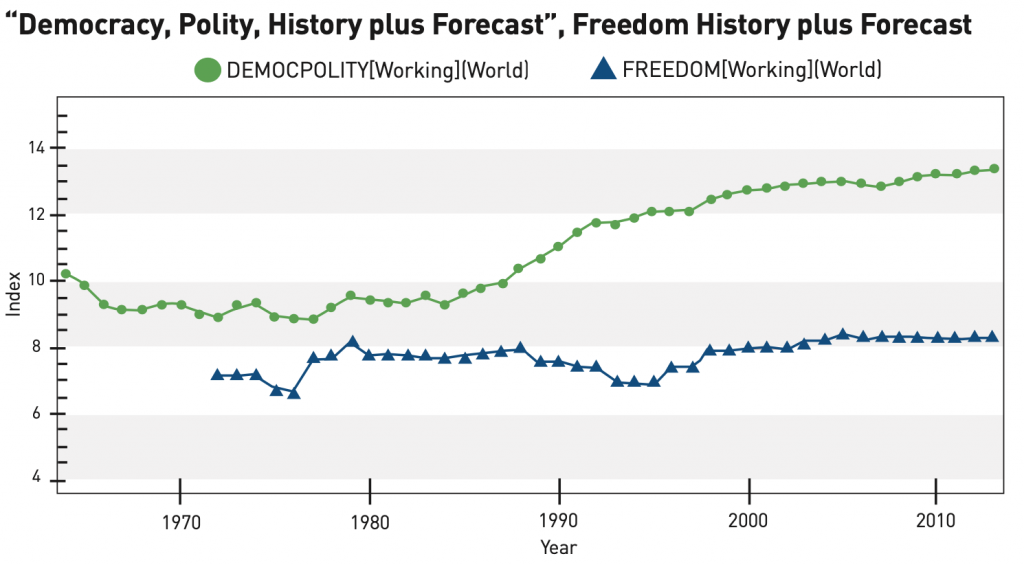

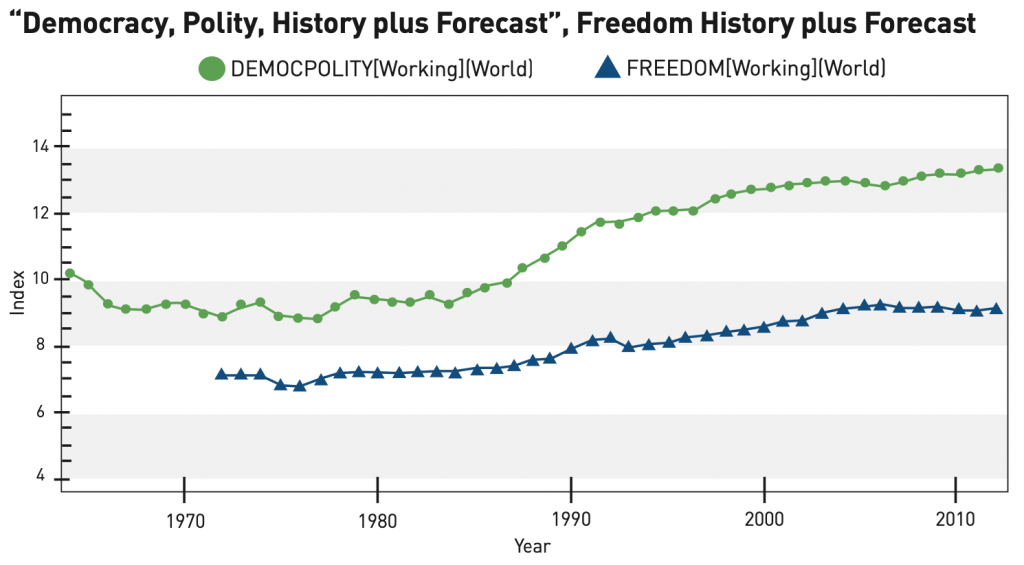

Flat rather than a decline in worldwide democracy

The charts below plot the spread of democracy using the 20-point Polity IV and Freedom House scores (reversed so that higher is more free). The first chart shows world democracy values with population weighting of countries. The second is simple country average. Freedom House scores have been basically flat, with Polity IV showing some incremental progress in recent years.

Chapter 2

Growing demographic crunch for everybody except sub-saharan Africa

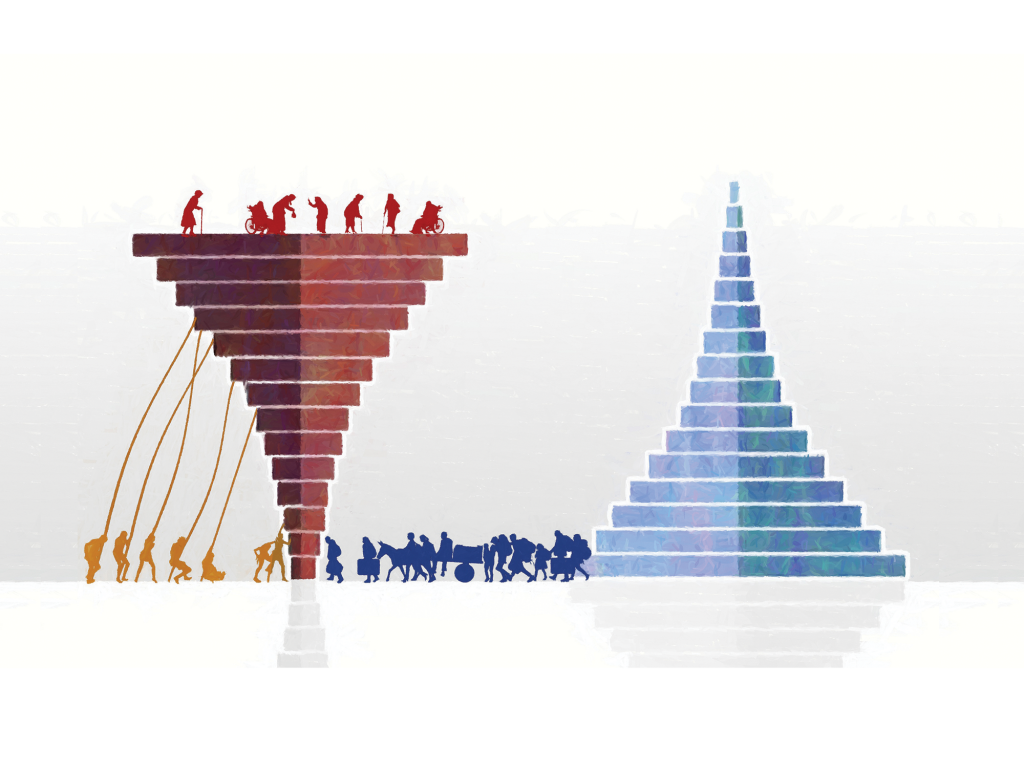

The world is entering a period in which the West’s postwar social-welfare system is under growing threat, as the global demographic structure is being turned upside down. It is not just the West, but also China and other middle-income powers, that will have to deal with an aging workforce and unsustainable health and pension costs in the next decade. For sub-Saharan22This section draws extensively from a prospective Atlantic Council publication on “Reducing the Risks from Rapid Demographic Change.” The study was sponsored by Zurich Insurance Group and conducted with the help of the University of Denver’s Pardee Center. The quantitative data were derived using Pardee’s International Futures Model. Full study, published in September 2016, is available at http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/reports/reducing-the-risks-from-rapid-demographic-change. African countries whose birthrates remain high, overpopulation carries big costs. Unless they can provide the burgeoning youth populations with education, skills, and employment, the youth bulges are a source of instability.

Managing demographic risk will be critical to every country’s future. Not making the right choices now can lessen economic potential for decades. There will be few second chances.

How prepared are high-income economies for the increased costs of pensions? In the fifty years between 1960 and 2010, public pension expenditures as a percentage of GDP doubled for high-income countries, from 4 to 8 percent. By 2035, they are forecast to grow another 3 percent, at a time of shrinking workforces.

These increased pension costs are coming at a time of rapid extensions in life expectancy. Since 1990, lifespans increased more than 2.5 years per decade on average. Increases in pensionable ages for all high-income countries, on the other hand, averaged less than one year per decade. Current forecasts are for life expectancy to increase by at least two years over the next fifteen years. The average pensionable age may need to be significantly higher—perhaps seventy years or above—for some countries by 2035, in order for governments to meet pension demand.

There is a similar story for healthcare spending. The increasing proportion of those aged eighty and over—a consequence of increasing life expectancy—will necessitate more extensive and expensive healthcare needs, such as in-home or long-term care. With healthcare costs rising, retiree savings will be depleted, putting the onus on governments to pay a larger share. But governments will be increasingly strapped; government spending is forecast to cover less than half of the healthcare spending needed—from 62 percent in 2015 down to 49 percent in 2035.

With demand growing for pension and healthcare spending, high-income countries, especially, face a catch-22 dilemma: cutting education, research and development (R&D), and infrastructure spending risks undercutting the higher productivity needed to offset declining workforces. With labor-driven growth increasingly in the past, high-income countries will either have to boost productivity to compensate for declining labor forces or face slowing economic growth.

According to McKinsey Global Institute, even if productivity were to grow at the rapid 1.8 percent annual rate of the past fifty years, the rate of GDP growth would decline by 40 percent, slower than during much of the recovery since the 2008 financial crisis. Some economists already predict a period of significantly slower growth because of declining workforces.23Ruchir Sharma, “The Demographics of Stagnation: Why People Matter for Economic Growth,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2016, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2016-02-15/demographics-stagnation

Emerging labor-saving technologies—robotics, increased automation, and more sophisticated artificial intelligence—could help offset the declines in workforces. But past technology breakthroughs have also led to new employment demands. Will there be enough skilled workers for high-tech industries if healthcare and pensions costs swamp national budgets, squeezing revenues for education and R&D?

Crunch comes later for middle- and low-income countries

Most middle-income countries have proportionally larger and younger workforces, putting them in a better position to prepare for the inevitable aging process. With fewer dependents, there is higher savings potential and more growth capacity. This report’s modeling shows, for example, that upper-middle-income countries will be able to devote more resources to education, closing the gap with advanced economies and moving them toward becoming knowledge economies.

However, middle-income countries will soon face many of the same demands for increased government healthcare spending as high-income countries. The share of healthcare spending in upper-middle-income countries will slowly decline, because of government inability to keep up with increasing demand. Upper-middle-income countries will also face pressures to increase public-pension spending. The need for pension spending as a share of GDP will increase by close to 5 percentage points by 2035.

Of middle-income countries, China faces a particularly daunting challenge. By the early-to-mid 2020s, with the sharp dropoff in working-age population, the pressures for more healthcare and pensions will erode the Chinese government’s ability to keep up with them. The annual Chinese pension-spending gap is currently $175 billion, and is forecast to grow to nearly $1.4 trillion by 2035. A failure to complete the middle-income transition during the few remaining demographic-dividend years would lead China and other middle-income countries to become old before getting rich.

Most low-income countries concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have the opposite problem. Instead of aging, their populations are youthful. The sooner they can bring down their high birth rates, the earlier they can move into the demographic bonus years in which they have the opportunity to boost growth. So long as fertility remains high, so do healthcare costs. Forty-eight percent of Afghanistan’s population is under the age of fourteen, and infant care is estimated to account for more than 40 percent of the country’s total healthcare costs.

The pace of fertility decline in sub-Saharan Africa, where total fertility rate (TFR) only dropped from 6.18 children per woman to 5.10 over the last twenty years, has been much slower than many demographers anticipated. Africa’s population is the world’s fastest growing. And even if fertility in Africa falls, the continent’s population will continue to grow rapidly because of the large cohorts entering childbearing ages during the next two decades. A continuing lack of a reduction in Africa’s fertility rate has big implications for the whole planet. Many demographers and environmental scientists had hoped to see a plateauing of population growth by mid-century. Without a drop in fertility, the world could end up with a population of eleven to twelve billion, instead of about nine billion, by the end of the century. A world with eleven billion people or more would put enormous stress on resources, at a time when climate change may also be affecting food production and the availability of water in Earth’s central belt.

Life expectancy at birth in Africa is the world’s lowest, at sixty years—nineteen years lower than in North America. Lack of access to clean water and sanitation, and poor health infrastructure, increase the risk of rapidly spreading communicable diseases, from intestinal parasites to Ebola. In sub-Saharan Africa, HIV/AIDS still ravages the population and maternal mortality is high, although declining.

The more resources can be devoted to education, the more low-income countries can maximize the approaching demographic bonus years. Still, low-income countries will have a hard time matching the resources that high- and middle-income countries can devote to the educational needs of their large youthful populations. With Africa forecast to provide one out of every four workers by 2050, a poorly educated African workforce has negative implications for long-term global growth potential. High levels of unemployed youths lead to civil conflict. One-hundred percent of the states marked as “Very High Alert” or “High Alert” on the Fragile States Index compiled by Foreign Policy and the Fund for Peace have very youthful age structures.

Good and bad scenarios

Aging and demographic transitions are a given, but a number of variables—such as medical advancements leading to healthier and longer-living populations, unanticipated drops in fertility rates in low-income African nations, or sustained high levels of migration from poorer to higher-income countries—could change the balance between risks and benefits for some countries.

What Happens When People Live Longer: This report’s longevity scenario explores a world in which advances in medical technology and treatments drive down mortality rates by finding cures for cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. This scenario uses France and China as illustrative examples. The consumption needs of all French retirees—measured as a percentage of GDP—increase by more than 14 percent by 2035. In the more rapidly aging China, the life-expectancy increase could drive a boost in consumption needs of more than 20 percent, translating into 200 percent growth in GDP share between 2015 and 2035. In this scenario, there is a stark contradiction between individual and societal needs. However desirable a longer and healthier life is for the individual, it comes with high costs for society.

What Happens with a Sustained Migration Influx: The rate of decline in Germany’s labor pool will accelerate between 2015 and 2020, and be a net drag on the German economy. A sustained influx of migrants would reverse this trend, so long as migrants become as productive as the average German worker. In such a scenario, migrants would reduce labor’s drag on economic growth by up to half, and potentially add more than $350 billion in GDP (relative to the base case) by 2035.

Reducing High Fertility in Africa: Today, the average African woman is expected to give birth to more than twice the number of children as women in the rest of the world. In a low-fertility scenario, average total fertility rates drop to near replacement levels by 2035. By 2035, Africans would just begin to enter the demographic-dividend years, boosting growth potential and per-capita incomes.

A sense of urgency needed by all

Political and economic measures can make a critical difference in terms of whether people all end up poorer and more unstable, or able to fully enjoy the benefits of growing longevity. With the aging process in full swing, high-income countries face a particularly difficult task of raising retirement ages, implementing efficiencies in healthcare, and reforming pension systems if they are to avert an economic slowdown. Middle-income countries have more time, but the accelerating aging process means they need to move quickly to align pension schemes to increasing longevity, and to build efficient healthcare systems. They have a big opportunity to close the education gap with high-income countries, boosting their productivity levels and attractiveness to foreign investment. Low-income countries need to bring down fertility quickly and increase educational standards if they are to maximize their advantages during the demographic bonus years.

Youth bulges remain important

While aging will become the predominant demographic trend, the number of countries—fifty—with a median age of twenty-five years or less will remain relatively large, though down from more than eighty such countries in 2010. Such youthful countries tend to have an oversized impact on foreign affairs because of the high correlation between youth bulges and the propensity for conflict, either inside or between countries. Since the 1970s, “roughly 80 percent of all armed civil and ethnic conflicts” started in countries with youth bulges24Global Trends 2030. Many of the countries with large youth bulges also figure high on state-fragility lists, and are unfortunately located in areas where climate-change impacts will be the greatest and food and water scarcities are a growing threat.

In 2035, most of these countries with still-large youth bulges will be concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, and in some parts of the Middle East—the Palestinian territories, Jordan, and Yemen. In the Western hemisphere, only Bolivia, Guatemala, and Haiti will retain their youth bulges. And in the Pacific, only East Timor, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands will do so. In South Asia, only Afghanistan will be youthful, although youth bulges will persist in tribal populations in Pakistan’s western provinces. Pashtun women in both Pakistan and Afghanistan give birth to more than five children on average.

The high fertility rates will have an explosive effect on countries’ populations, especially those in the Middle East and South Asia. If current fertility trends persist, countries like Afghanistan and Yemen will see a doubling of their populations between 2005 and 2030, and a tripling by 2050. Pakistan’s population—part of which is beginning to age—will nevertheless see a 50 percent increase, reaching 240 million by 2030, which will make it the world’s fifth-most-populous country. Saudi Arabia—which is also beginning to age—will have a 58 percent increase to twenty-seven million between 2005 and 2030. Overall, the Middle East will add roughly 290 million people in the 2005-30 period.25Adele Hayutin, Critical Demographics of the Greater Middle East: A New Lens for Understanding Regional Issues (Stanford, Calif: Stanford Center on Longevity, 2009), http://longevity3.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Critical-Demographics-of-the-Greater-Middle-East.pdf.

The population explosions make it difficult to turn youth bulges into demographic dividends for the economy. Afghanistan, Yemen, the Palestinian territories, and a number of sub-Saharan countries are projected to see gains in their working-age populations of around 130 percent.26Ibid. No economy could absorb such numbers. In addition, the persistence of high birth rates among minorities within countries will cause potential imbalances and tensions with majority populations. Kurdish fertility in southeastern Turkey has stalled at about four children per woman. In Israel, the ultra-Orthodox Jewish minority, or Haredim, and the Arab sectors will double their absolute numbers over the next twenty years, while the percentage of non-Haredim and secular population—with lower birth rates—will drop from 51 percent in 2010 to 42 percent in 2030. However, the non-Haredim and secular populations provide the vast majority of the Israeli workforce.27Amir Mizroch, “Israel 2030: A Hard Look at the Hard Numbers,” Jewdyssee (blog), April 13, 2012, http://www.jewdyssee.com/2012/04/15/israel-2030-a-hard-look-at-the-hard-numbers-2/. Such a reduction in numbers cannot help but negatively impact the economy.

Migration and mobility

Migration and mobility could be important factors in ameliorating the workforce and skills gaps caused by aging, although rising political and social opposition to immigration may act as an obstacle. Populations in youthful countries could have increasing opportunities so long as they can acquire the skills, and if immigration barriers do not prevent mobility. The first globalization of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw bigger movements, proportionally, of people emigrating (mostly from Europe), and also high rates of return to their home countries.28Global Trends 2030, p. 24; Ronald Skeldon, Global Migration: Demographic Aspects and its Relevance for Development (New York: UN Population Division, 2013), p. 2, http://www.un.org/esa/population/migration/documents/EGM.Skeldon_17.12.2013.pdf.

Circumstances appear even more favorable to movements of people in coming decades, both internationally and within countries. According to the UN, there were 232 million international migrants in 2013. Between 1990 and 2013, the number of such migrants rose by more than seventy-seven million or by 50 percent, with “much of that growth between 2000 and 2010.”29United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, International Migration Report 2013 (New York: United Nations, 2013), p. 1, http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/migration/migrationreport2013/Full_Document_final.pdf. Interestingly, though, the proportion of the world’s population who are international migrants has stayed around 3 percent since 1995.

Europe and Asia currently host nearly two-thirds of all immigrants; in 2013, there were seventy-two million immigrants in Europe and almost an equal number in Asia. North America hosted the third-largest number (fifty-three million), followed by Africa (nineteen million) and Latin America (nine million). The United States has by far the largest number of immigrants: forty-six million reside in the United States, equal to nearly 20 percent of the world’s total. The Russian Federation hosts the second-largest number—eleven million—followed by Germany (ten million), Saudi Arabia (nine million), and the United Arab Emirates and United Kingdom (eight million each).30Ibid.

More recent trends indicate a shift away from Europe and North America, especially increasing South-South flows. In 2013, “Asia-Asia was the largest migration corridor in the world, with some 54 million international migrants” leaving one Asian country for another.31Ibid. The Latin America-US corridor, which was the largest one from 1990-2000, has been steadily declining.32Ibid. The birth rate in Mexico—which used to provide the largest number of migrants—has gone down as the middle class there has increased. Many more people are finding opportunities at home rather than being forced to emigrate. All but three of the largest migration corridors in the world have a destination in the South. Increasingly, too, the majority of immigrants are moving within the region in which they are born.33Ibid.

As country populations age, the number of immigrants who will leave is likely to decline. Since the late nineteenth century, the majority of immigrants have been young adults. As their proportions decline in aging countries, young people are likely to have more job opportunities at home, lessening the incentive to leave. The big exception will be for students, the numbers of whom are increasing at a very rapid rate. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the number of international students more than doubled between 2000 and 2011, with almost 4.5 million university-level students enrolled outside their country of origin. Asians—particularly Chinese, Indian, and Korean—constitute a majority of all students going abroad to complete their educations. As with permanent migration, the destinations are beginning to change, with Australia, New Zealand, Spain, the Russian Federation, and South Korea rising for an increasing share of international students, while the United States and Germany are beginning to lose their share. The United States, which still has by far the largest share of international students, nevertheless slipped from 23 percent to 17 percent between 2000 and 2011. Increasingly, international students are also staying on, with an average of 25 percent becoming permanent immigrants in OECD countries. For some receiving OECD countries—including Australia, Canada, the Czech Republic, and France—that rate is more than 30 percent.34Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Education Indicators in Focus (Paris: OECD, 2013), http://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/EDIF%202013–N%C2%B014%20(eng)-Final.pdf.

For all the increasing movement of young people, it is not clear if that will make a huge demographic difference for most countries in which they settle. For example, net migration is projected to offset Europe’s population decline until 2020, when the surplus of deaths over births will be so great that even increasing migration is unlikely to reverse population decline. The big exception is in the United States, where migration has already greatly boosted population growth and will become increasingly important as US birth rates decline and net migration becomes more important than natural increase in the early 2030s.35United Nations, International Migration Report, pp. 14-15. That is, of course, unless there is a movement to expel illegal migrants and stop large-scale immigration.

Internal migration is a more difficult subject to analyze for structural patterns, because of the patchy data. Available data would indicate that “where the distribution of the population in urban areas approaches about three-quarters of the population, the number of internal migrants declines.”36Skeldon, p. 12 Internal migration in the United States has been dropping, with a leveling off of urbanization. Aging is also a factor. The number of internal migrants in Japan has dropped since the 1970s, when Japanese fertility rates began to fall below replacement level. In places like sub-Saharan Africa, where urbanization rates are increasing, the move to the cities is picking up momentum despite government efforts in some African countries to stem the flow. China presents an interesting case, as its economic growth has been fueled by the migration of peasants to the cities—more than 229 million, of which two hundred million moved without getting formal permission to change residency. China is counting on the continued movement to bolster economic growth, although it is unclear—with the youthful proportion declining—if it can continue to match former rates of migration.37Skeldon, pp. 16-17.

Urbanization

For the first time in human history, a majority of people are now living in urban areas. That number will climb to nearly 60 percent by 2030, in contrast to roughly 30 percent in 1950. Sub-Saharan Africa—where the urban proportion of population is below 50 percent—may have the highest rate of urban population growth, although Asian urban populations will continue to grow. According to the UN, between 2011 and 2030, 276 million more Chinese and 218 million more Indians will live in cities, accounting for 37 percent of the total increase for urban population in 2030.38United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Urbanization Prospects: The 2011 Revision (New York: United Nations, 2012), http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/WUP2011_Report.pdf. China alone will have 242 cities in the McKinsey Global Institute’s top six hundred, which, according to its estimates, “will generate nearly 65 percent” of global GDP by 2025. Other countries providing significant additions to the world’s urban population include Bangladesh, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, and the United States.39Ibid.