By Sahar Halaimzai, Metra Mehran, and Marika Theros

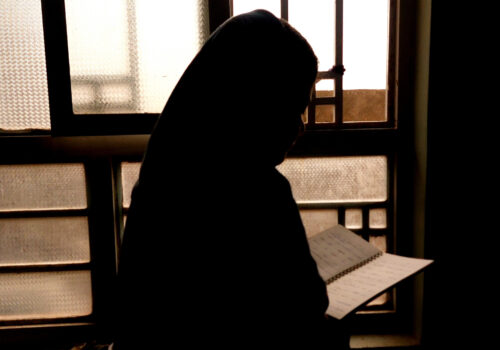

Since retaking Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban has issued dozens of repressive decrees designed to systematically oppress the women and girls of the country. In the interactive audio timeline below, you can hear directly from Afghans on the profound impacts of the escalating gender apartheid in Afghanistan. These first-hand stories have been collected over the past 18 months through interviews with women inside Afghanistan.

To protect these women from the significant risks associated with speaking out against the Taliban, we’ve taken several precautions: Their names have been changed, and, in some instances, their stories have been merged. We have also not used their real voices. Instead, the audio stories you will hear were recorded by women and girls who have been evacuated from Afghanistan since 2021. These women’s stories of endurance and resistance reveal the stark realities of life under a legal system that curtails freedom, stifles potential, and erodes dignity, yet they also illuminate the unyielding spirit and strength of each woman and girl. Their voices are a reminder of the interconnected struggles of all people globally in the pursuit of dignity, rights, and equality.

Afghan women did not have a real seat at the table in the United States’ “peace” deal with the Taliban. They are now demanding the world’s help in dismantling systems of oppression and rebuilding a society where equality and human rights are realities for all.

This initiative is a joint project of the Civic Engagement Project and the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Litigation Project.

The onslaught of decrees

In 2020, after nearly twenty years of war, the United States signed an agreement with the Taliban to unilaterally withdraw US forces from Afghanistan. The so-called peace process did not substantially include or account for Afghan women, whose concerns about the escalating, targeted violence against them and pushback against the myth of a reformed “Taliban 2.0” were largely ignored. By August 2021, Taliban soldiers were on the doorstep of Kabul; by August 15, they had taken over the city, signaling the collapse of the Afghan republic.

Ten days later, the Taliban issued its first directive, instructing women and girls in Kabul to remain indoors, justifying it on the grounds that Taliban soldiers were not trained to respect women and therefore could not guarantee their safety outside. The rise of the Taliban regime has not only marked a significant political upheaval and one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world today, but it has also ushered in a rapid regression for women’s rights in Afghanistan. Despite initial pledges of moderation, the Taliban has aggressively dismantled two decades of progress made by Afghan women and girls.

The group has done this by issuing around eighty decrees that directly target women and girls, demonstrating the systematic, institutionalized, and punitively enforced nature of gender apartheid in Afghanistan. In some instances, these decrees are punitive, particularly in places where women are resisting the Taliban. With about 60 percent of Afghanistan’s population under the age of thirty, the vast majority of Afghans are encountering the Taliban’s oppressive rule for the first time. “The shapes and sounds of girls and women evaporated from our streets with every new decree,” observes Malalai.

Some foreign officials distort or diminish the severity of gender apartheid in Afghanistan by framing it as a reflection of cultural or religious norms, reinforcing Taliban propaganda. However, international law unequivocally rejects the use of culture or tradition as justifications for infringing upon fundamental human rights. Moreover, Afghan and world Islamic scholars have condemned many Taliban decrees against women as un-Islamic. And prior to the Taliban takeover, women were making major strides in gender equality across every sphere of life—economic, cultural, social, and political—indicating that these decrees are not a reflection of culture so much as a mechanism of control.

These concerns are particularly acute for women from ethnic, religious, or linguistic minorities, such as the Hazara, Tajik, Hindu, and other communities. Women from these groups face compounded vulnerabilities due to their distinct identities and increased visibility, making them even more susceptible to targeted violence in Afghanistan’s current climate. This double burden borne by minority women under these decrees is a harsh reality that often goes unnoticed.

The Taliban’s movement restrictions have effectively trapped women within their homes and within Afghanistan’s borders. Prohibiting international travel without a mahram quashes any possibility of seeking refuge or opportunities abroad, leaving female activists and those in peril with no escape. The Taliban’s movement restrictions have created an environment where female-headed households face disproportionate hardships, because they cannot travel without a male guardian to sites for aid distribution. Their struggle for basic rights and survival under these oppressive decrees requires urgent international attention and support.

A vicious cycle of oppression

The significant increase in the systematic oppression of women and girls has touched every aspect of daily life, as reported by international organizations. This includes bans on their employment with United Nations (UN) offices and non-governmental organizations. The implications of these decrees are extensive and complex, beyond immediate issues such as access to health care or economic opportunity.

In the long term, the systematic denial of basic human rights, particularly the lack of educational access for girls, exacerbates disparities in wealth, health, and education. These challenges create a cycle of disadvantages with profound ripple effects that will take generations to rectify.

The result is a severe mental health crisis among Afghan women and girls. Afghanistan has now become one of the few countries globally where suicide rates for women surpass those of men, an alarming indicator of the extreme psychological impact of the Taliban’s oppressive policies. Observations from UN representatives and human rights advocates corroborate this connection. Increasingly, UN officials and international expert assessments declare the treatment of women by the Taliban as tantamount to gender apartheid. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres said last year, “in Afghanistan, unprecedented, systematic attacks on women’s and girls’ rights and the flouting of international obligations are creating gender-based apartheid.”

The Taliban’s mechanisms of enforcement

Through coercion, the establishment of new institutions dedicated to policing women, and the repurposing of existing security infrastructures, the Taliban has enforced its decrees with efficiency. On their very first day in power, Taliban officials closed the Ministry of Women’s Affairs and reinstated the Ministry of Vice and Virtue, deploying Taliban soldiers to strictly enforce their decrees. Women have been arbitrarily detained, subjected to torture, and released only under conditions that their families enforce strict compliance with Taliban rules at home. The number of cases of women detained and released is not public, nor are the suicides of women after their release reported adequately.

Furthermore, the Taliban has repurposed the security infrastructure established by previous Afghan governments, turning it into a tool for the systematic oppression of women and girls. This infrastructure, once meant for public security, now perpetrates enforced disappearances, arbitrary detentions, torture, and even executions. Any organized resistance is crushed through raids, violence, arbitrary arrests, and torture, showcasing the Taliban’s unwavering dedication to maintaining their regime of gender-based restrictions.

This enforcement strategy also extends to punishing male family members for the perceived transgressions of their female relatives, compelling men to ensure the women in their families obey the Taliban’s decrees. This policy both directly subjugates women but also coerces men into participating in this oppressive system.

The Taliban has also dismantled nearly all mechanisms for legal recourse previously available to women. The Attorney General’s Office has been transformed into the General Directorate for Monitoring and Follow-up of Decrees and Directives, granting Taliban leaders unchecked authority to enforce their will without due process. By abolishing foundational legal structures, including the constitution, human rights commission, penal code, special courts, and units dedicated to combating violence against women and children, the Taliban has obliterated any legal protection for Afghan women.

Accountability under international law

The international community should utilize its extensive network of international laws, treaties, commitments, and partnerships to find ways to counter the Taliban’s actions in Afghanistan and hold the regime accountable for crimes against humanity.

This requires a multi-pronged strategy and mutually reinforcing actions that can enable women of Afghanistan to seek justice and protection. Individuals and advocacy groups can undertake impact litigation or another nation could file a case against Afghanistan under existing legal frameworks such as the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women or the UN Convention on the Political Rights of Women. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has been examining the situation in Afghanistan following the release of its Policy on the Crime of Gender Persecution in late 2022. To date, however, the ICC prosecutor has not filed any charges against Taliban members, nor have there been any state-initiated proceedings at the International Court of Justice.

While current legal frameworks on gender persecution and discrimination provide some pathways to justice, they do not capture the full extent of the crimes perpetrated against the women and girls of Afghanistan. The Taliban is committing inhumane acts involving arbitrary arrests, imprisonment, and torture in the unique animating context of an institutionalized regime of systematic gender-based oppression and domination for the purpose of entrenching power and maintaining the regime. Therefore, Afghan women, in solidarity with international human rights organizations, gender and legal experts, and activists, have been demanding that it must be called out for what it is: gender apartheid.

Today, there is a movement to expand the definition of apartheid to include gender apartheid in both international and national laws. In March 2023, dozens of women’s rights defenders launched the End Gender Apartheid Campaign. In October 2023, the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Litigation Project, with the Global Justice Center, issued a joint letter and legal brief urging UN member states specifically to codify the crime of gender apartheid in the draft crimes against humanity treaty presently under consideration by the UN General Assembly’s Sixth Committee (Legal). Codification of gender apartheid in the potential crimes against humanity treaty would open up pathways to accountability not only for individual perpetrators but also for third-party states and institutions. It would also foster international solidarity, highlighting the severity of the situation in Afghanistan and leveraging the accompanying stigma to criminalize Taliban actions.

By combining existing legal frameworks related to gender persecution and discrimination with activism for recognizing the crime of gender apartheid, the international community can formulate a coordinated and complementary response. This approach employs a range of international and domestic legal tools and recognizes that these pathways are not mutually exclusive but rather mutually reinforcing, working together to tackle the ongoing plight of women and girls in Afghanistan squarely, effectively, and holistically.

For a comprehensive list of all Taliban decrees, visit the US Institute of Peace’s Tracking the Taliban’s (Mis)Treatment of Women.

Stories of resistance

Sahar’s story

Sahar, an employee at a government institution in a northern province of Afghanistan, found her world transformed with the collapse of the republic and Taliban takeover. Today, more than 65 percent of women feel physically unsafe and 90 percent of women report high mental distress, according to UN Women. Sahar, like many, navigates the repercussions of a complete erosion of women’s rights with little or no support. Driven to improve the collective resilience of Afghan women facing adversity, she initiated psychotherapy programs in her province. These programs, tailored for women and girls, offer a sanctuary where they can share their experiences and find support.“ In the darkest hours, we find our true strength,” Sahar says “My hope is that every Afghan woman remembers her worth and the power she holds. We are the backbone of this nation.”

Aisha’s story

Despite the dire circumstances enveloping the region, women in a northern province of Afghanistan recently launched more than ten workshops focusing on sewing and carpet weaving, helping women earn an income and come together in solidarity. Moreover, several women in the group have started language and mathematics classes linked to religious schools, catering to girls beyond the seventh grade. However, as Aisha reflects on the way in which women in her community have come together, she cannot help but acknowledge the broader, alarming context. Around 20 percent of households in Afghanistan are headed by women. With the majority of job opportunities now inaccessible to women, the ramifications for Afghanistan’s fragile economy and the Afghan people are severe. Today, close to nine million Afghans are facing acute hunger. The Taliban-imposed restrictions on freedom of movement for women have exacerbated the crisis, as many vulnerable women and families are trapped and cut off from life-saving support.“ In the face of these adversities, it’s remarkable to witness the surge of determination among our women,” Aisha says. “The recent rise of workshops represents so much more than just skill-building; it’s an act of hope, a way for countless women and girls to find meaning and sustain their families. And the most incredible part? Every single one of these workshops is a testament to women’s resilience, as they are all led by women themselves.”

Hanifa’s story

Hanifa, an eleventh-grade student, confronts the stark reality of educational closures alongside other girls in the northeastern province of Takhar. Since September 2021, all Afghan girls over the age of twelve have seen their education indefinitely banned. As a result, a staggering 2.5 million Afghan girls, more than 80 percent of all school-aged girls and young women, are now out of school.“ With the schools closed, both my sisters and our neighbor’s daughters were left directionless,” Hanifa says. “We tried to establish some sense of normality by initiating language and mathematics classes, but those efforts were short-lived. As the days passed, we increasingly relied on mobile phones for a semblance of connection to the outside world. In a particularly difficult moment, I turned to my mother, sharing my fears and doubts about our future.” Acting on this concern, her parents became aware of a local woman who had set up a sewing training program, and they promptly enrolled Hanifa, her sisters, and their neighbor’s daughters. Beyond the immediate challenge of school closures, Hanifa’s dreams of further education and exploration have been challenged. She once harbored aspirations of attending university, traveling, learning new languages, and experiencing the world. Though the sewing classes are a far cry from these dreams, she says they have provided an essential ‘underground’ support system; one, however, that creates risk for all those involved.