By Mathew Burrows and Anca Agachi

Pandemics have often proven turning points in history. The Black Death in the 1300s helped undermine feudalism, while some believe the Spanish flu tipped the balance in favor of the Allied cause in the final days of the First World War. Yet the current one has been less a disruptor than an accelerator of trends that were already fraying the fabric of the post-Cold War international system long before the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2.

Two grueling years into the pandemic, it feels like we’ve seen it all. But it may just be that we ain’t seen nothing yet. Many of COVID-19’s effects on twenty-first century human civilization, in fact, are not yet visible. Much of the non-Western world still awaits sufficient vaccines, and the fallout from pandemic-induced economic downturns will unfold over the course of years, just as the repercussions of the 2008 global financial crisis did. Meanwhile, Sino-US hostility exacerbated by the public-health crisis raises the specter of large-scale conflict after decades of relative peace among the world’s most powerful states. Also suffering serious and hugely consequential setbacks: the march of globalization and the multilateralist architecture designed after World War II to maintain peace.

So what lies ahead? Well into the 2020s, COVID-19 will cast a long shadow over communities, workplaces, markets, battlefields, and negotiating rooms. But even as the centrifugal forces driving the world away from multilateralism and toward multipolarity accelerate, the future is not fixed. We humans have agency in shaping it.

Here, building on our work on strategic foresight and global trend analysis inside the US intelligence community and outside government, we envision three alternative worlds in 2030. The intention is not to predict what’s coming next, but rather to highlight the factors that could lead the world in one direction or another—and thus provide insights that can spur strategists to prepare for possible challenges, plan for potential opportunities, and pursue a brighter future by making prudent decisions in the present. Instead of a crystal ball, what we offer are portals to different universes.

The scenarios in this ten-year forecast are informed by ten significant trends outlined below that are already transforming today’s world and likely to shape the world a decade from now as well.

Ten trends shaping the current and future world

1. The vaccine miracle—and cautionary message

The development of COVID-19 vaccines was remarkably rapid, with those most vulnerable to the virus in rich countries inoculated within a year of the pandemic breaking out. If vaccine development and distribution had been slower, the death toll from the disease would now be several times higher. The tragedy, however, is that poorer countries still lack enough vaccines; although a small majority of the world’s population has now received at least one dose, coverage remains highly uneven; in Africa, for example, less than 12 percent of the population has received at least one dose as of December. The longer a substantial portion of the world’s population remains unvaccinated, the higher the risk that more contagious variants like Delta and Omicron emerge.

Absent the vaccines, a much deeper global recession would have also ensued. Western countries would have gone into greater debt to cover health and unemployment costs, and struggled more to emerge from the crisis. The World Bank anticipates that economic growth in advanced economies will be almost twice as fast in 2021 as it was after the Great Recession. The fact that many Western policymakers were involved in or closely observed the response to the global financial crisis was an advantage: They pushed for higher stimulus than in 2008-09.

Will the current crisis yield similar wisdom for subsequent ones? The scale of this pandemic—only comparable to the Spanish flu a century ago—should not lull the world into thinking another one won’t emerge in the near future. There is peril in wasting this opportunity to build more global resiliency, particularly for those without the means to weather such disasters. Will lessons be learned from the inequitable delivery of vaccines? Will the developing world gain the manufacturing capacity to ensure speedier distribution of vaccines next time? There should be no “losers” in a vaccine scramble. Yet who wants to bet that the developed world has learned this lesson—or that it grasps the long-term damage already done to its reputation in the rest of the world?

2. Technology’s double-edged sword

If science came out of the pandemic a winner, technology was a close second. Without computers and connectivity, the lockdowns could have ground most economic activity to halt. Managers were surprised by the productivity of remote work. Some types of work, however, could not move online. Those in service jobs—including many ethnic and racial minorities—could not stay at home and were thus disproportionally affected by the COVID-19 crisis.

The future of work will be hybrid, with in-person and remote aspects. While telework has been around for decades, it took a transformative event to force the paradigm shift. To the extent that workers can benefit from a more flexible routine, this could be a positive development for keeping more people in the workforce—helping to persuade working mothers (who were disproportionately impacted by the economic fallout of the pandemic) to reenter and seniors to stay employed. But other challenges, including long-term job insecurity as automation progresses, will offer more tests but few easy solutions.

3. Here comes deglobalization

The developing world has lost many of the benefits of globalization—at least for the time being. A significant portion of the once-rising global middle class slid back into poverty as a result of the pandemic and its economic ramifications, reversing perhaps humanity’s biggest achievement in recent decades. Without targeted policy interventions, the world is verging on return to a two-speed world of “haves” and “have nots.” With the pandemic still raging in the developing world, the full extent of the damage to that new global middle class remains unknown. Some countries will gain strength from overcoming pandemic-related challenges, but the weakest will probably experience growing political instability and even state failure.

For many poor countries, recovery from the dislocations of deglobalization is further complicated by other challenges. The threat of food crises, for example, has increased for nations suffering endemic conflict plus the added strain of the pandemic and global economic slowdown. At least 155 million people in fifty-five countries and territories were estimated to be in danger of serious food deprivation or worse in 2020—an increase of around twenty million people since 2019—with catastrophic conditions in countries such as Afghanistan, Yemen, Burkina Faso, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Another challenge in surmounting the consequences of deglobalization is climate change. Africa’s gross domestic product, for example, could decline by 15 percent by 2030 as a result of climate-related disasters and spending on efforts to adapt to a warming world, according to the Economic Commission for Africa. African leaders aiming to overcome these challenges can look to trade and economic-reform opportunities. The African Continental Free Trade Area officially started trading on January 1, 2021, and estimates suggestthat trade liberalization could increase African real income by $450 billion by 2035. Such a development could blunt the damage inflicted by COVID-19 and help boost the continent’s post-pandemic economic recovery.

4. The deepening of domestic disorders

Today there is more inequality not just between developed and developing countries, but also within many of these countries themselves. This is the second major global economic crisis in a little more than a decade, battering those who had already suffered setbacks in establishing their careers or who had only recently picked up the pieces from the 2008 financial crisis. In the United States, for instance, many women left the workforce during the pandemic to take care of their kids when childcare centers closed and schools switched to remote learning, while ethnic and racial minorities have continued to suffer from higher unemployment than the working population as a whole.

In advanced economies, the relatively rapid recovery is a hopeful sign for those hurt economically by the pandemic. Yet the future of work will remain turbulent, particularly for the unskilled and semiskilled. The pandemic spurred employers in some industries to invest more in robotics and automation rather than recruiting and training workers. Even before the coronavirus crisis, in fact, there were numerous forecasts that greater automation was coming. That practice could now speed up, further increasing inequality and job insecurity.

The Internet and social media—so vital in maintaining economic activity—have also unleashed forces that threaten democracy. On the one hand, new digital platforms support freedom of expression, offer new possibilities for democratic participation, and provide access to diverse information. For authoritarian leaders, the expansion of information and communications technology can be a menace in providing citizens with powerful tools to mobilize against the regime. On the other hand, new technology platforms give birth to information bubbles and polarization, increase the effectiveness of misinformation and disinformation, and promote a nonconsensual culture of debate. Hate speech and conspiracy theories pose an increasing danger to civic trust and democratic political order. In democracies, extremist and populist parties have been able to capitalize on these dynamics. These technologies also enable corporate and state entities to engage in potent new forms of surveillance and information manipulation.

Tech companies oppose government measures to address these concerns that go against their business models, while governments themselves worry about the impacts of such measures on innovation and national competitiveness. With more regulations increasingly likely in Western countries to guard against harm to children and better protect privacy, the burning question is how to balance these potentially conflicting objectives.

5. Meet the New World Order 2.0

The pandemic could have been a catalyst for a rebirth in global cooperation, but instead it revealed just how frayed the world’s multilateral structures are. This largely proved to be a time for the nation-state to take charge, as countries closed borders, instituted lockdowns, and looked after their own interests.

Given how much mutual distrust the pandemic has sowed between China and the West, it will be hard for them to reach consensus on reforming the World Health Organization. That same distrust is evident in other international institutions. The United Nations Security Council has been paralyzed by Russia and China working together to wield their veto power. While the Biden administration has recommitted the United States to the Paris climate accord, it has yet to move ahead on an effort with European nations to reform the World Trade Organization, which is critical to the running of a rules-based trading system. We are living through an age of multipolarity without multilateralism.

After the end of the Cold War, the George H.W. Bush administration talked about a “new world order.” It envisioned a return to the original conception for a post-World War II multilateralist global order that never took shape due to divisions between the Soviet Union and United States. In such a world, so the thinking at the time went, countries would cooperate to solve common problems and strive for Western values such as democracy and liberal markets.

Three decades later, the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. Sino-US tensions make military conflict between great powers conceivable again for the first time since the end of the Cold War. The Biden administration has chosen not to reverse or even temper the growing US hostility toward China that was a hallmark of the Trump administration. China, meanwhile, is rushing headlong to claim its perceived rights as a great power, determined to call into question any US pretense to unrivaled global leadership.

Just beneath the surface of US angst are fears of a world in which China displaces the United States as the dominant political and economic player. In the words of President Joe Biden, China has “an overall goal to become the leading country in the world, the wealthiest country in the world, and the most powerful country in the world. That’s not going to happen on my watch.”

China will probably overtake the United States later this decade or early in the next one to become the world’s biggest economy as measured by market value. Most Europeans believe that China is already the dominant economic player, according to the Pew Research Center. But the US public is not ready to concede that preeminent position, which suggests that once the shift happens it will deal a psychological blow to Americans—having the effect of pulling the rug out from under the nation’s “exceptional” destiny. Also striking in the Pew polling is that neither age nor political-party affiliation was a big factor in whether or not the American public had unfavorable views toward China, heightening the sense of a unified America engaged in a contest with China in which perceived defeat would be keenly felt. For Europeans who lost empires some time ago, the idea that the United States would be immune from relative economic decline seems unrealistic.

The United States and China may well find a pragmatic framework for cooperating on select mutual interests. Significant advances—the Helsinki Accords’ human-rights agenda and arms-control agreements, for example—were made during the Cold War when it suited Washington and Moscow. One should not dismiss such possibilities. Yet the chances of US and Chinese leaders collaborating to build a more multilateralist world look dim, at least for the next decade.

Biden hopes to constitute a democratic order with US allies and partners, excluding China, Russia, and other authoritarian countries. On most global issues, this would be unworkable—and perhaps dangerous. The Versailles peace settlement after World War I ignored the Soviet Union and Germany, with disastrous consequences. No viable global order is possible without inclusion of all the major powers, including Russia and China.

China does not have any kind of multilateralist blueprint in mind for the global order and doesn’t want Western-designed global institutions to set the rules for international relations. Chinese leaders know that the county’s breakout as a global power on a par with the United States won’t be frictionless. What China wants is a world that won’t hinder its brand of state capitalism and authoritarian rule. As a rising power and former victim of colonial exploitation in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, China is sensitive to any perceived curbs on its sovereignty, believing that its great-power status gives it the right to regional, if not global, sway. Chinese leaders want to find ways to circumvent (and perhaps, over time, even supplant) the United States, which has used the web of multilateral institutions to anchor its global power.

6. Climate change: Where some Sino-US competition might actually be good

Even on issues like climate change, where China and the United States have obvious common interests, cooperation and competition will likely both occur. That may, in fact, be the best outcome.

Biden has talked about the United States producing the needed technology to fight climate change, yet as the Financial Times has noted China “dominates the sourcing, production, and processing of key clean-energy minerals worldwide” and is the global leader in clean-tech manufacturing. It controls around 70 percent of lithium-ion battery metals and processing along with 90 percent of the rare-earth elements used in high-tech weapons systems and offshore wind turbines, while making three-quarters of the planet’s solar panels, according to the paper. If the United States deploys tariffs or sanctions against China’s climate-related technology in a similar manner to how it has tried to combat the Chinese telecommunications company Huawei, then the global fight against climate change will suffer. At the same time, China is an egregious emitter of greenhouse gases and is having difficulty weaning itself off coal, despite its promises to do so. For all developing states, including China and India, the choice between growth fueled by cheap, dirty fuels and more expensive green-energy sources is a challenging one. The United States and European Union will need to use carrots and sticks to get China, other developing countries, and perhaps even some allied advanced economies like Australia to cut back on dirty fuels if the world is to achieve and accelerate its timetable for a carbon-neutral world.

Climate change is too important a global concern to be endangered by Sino-US competition, but it would be naïve to think that neither side will seize on the issue to gain advantage over the other. Some horse-trading between Beijing and Washington will inevitably have to happen if they are to reach their climate goals. Sino-US competition over which country is the global leader in the climate-change fight might even be a good thing as long as the rivalry stays does not swerve into military conflict.

7. A middle-power balancing act against a bipolar world

While the Sino-US relationship looms ever larger over the future of international relations, middle powers have nevertheless found ways to play critical roles (for good or ill) in a world in which power continues to diffuse. Despite the many predictions of its arrival, ours is not a bipolar world—not yet, at least. Even Asian nations that are highly dependent on China economically are hedging their bets, as many expand their security cooperation with the United States. European allies share US concerns about Chinese intellectual-property theft, forced technology transfers, and takeovers of businesses in strategic sectors with sensitive technologies. But they still want to cooperate with Beijing—not just compete—and are opposed to any economic decoupling between the West and China. These Asian and European partners seek to head off a military conflict between the United States and China, which could destroy the global system. They are pursuing their policy agendas independently of Washington and Beijing.

For the United States, this state of affairs has benefits and drawbacks. While Washington can’t assume its allies and partners will automatically fall in line with its agenda, those allies and partners can take the lead on common objectives when the United States becomes preoccupied elsewhere. The European Union and Japan, for instance, sought to keep the flame of free trade alive when the United States disengaged from that effort during the Trump years. In just four years, the EU negotiated major trade deals with Japan and South Korea, reaching additional agreements with Canada, Singapore, Vietnam, and China. Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe didn’t let the idea of the Trans-Pacific Partnership idea die when Donald Trump pulled the United States out of the trade agreement, remaking it as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in hopes of getting a post-Trump America to join. Japan also joined the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Other major Asian economies, including Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore, signed onto both CPTPP and RCEP.

8. Europe’s quest for strategic autonomy

While “strategic autonomy” has long been a goal for many Europeans, the Trump presidency and the contempt that the former administration showed America’s allies inspired a revival of European interest in being independent—not just from the United States but increasingly from the growing power of China as well. Protecting the European Union’s digital sovereignty by enforcing regulatory standards on foreign tech companies operating in Europe has turned out to be one of the more promising ways for Europe to augment its strategic autonomy. Lacking tech behemoths comparable to those in the United States and China, the EU has aimed to use its power as one of the world’s largest marketplaces to set regulatory standards for the rest of the planet. Brussels has spearheaded data-privacy protocols for the Internet, which have already influenced privacy standards or laws instituted by California and China. It is now trying to establish standards on artificial intelligence (AI). Along with trade deals, these efforts have boosted the EU’s economic weight.

In the military realm, there have been renewed effort to develop a European defense identity alongside NATO. Without major new investments in defense, however, European leaders will still rely on the United States to deter Russia. Yet Europeans can take on more responsibility for other defensive tasks such as policing Europe’s external borders for illegal migratory flows and criminal activity. Like the United States after its exit from Afghanistan, European governments are loath to engage in more nation-building. The reality is that EU member states would be dependent on Washington for intelligence and airlift capabilities even for a medium-scale intervention such as the counterterrorism mission that France is drawing down in the Sahel.

9. An emerging Asia-Pacific hedging strategy

Highly dependent on China as the economic motor for the region, some Asia-Pacific nations see the United States as a critical counterweight against Beijing. For them, Sino-US tensions escalating toward open conflict would be as alarming as a US exit from the region.

China’s aggressiveness in recent years has revived and expanded the focus of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad, involving Australia, India, Japan, and the United States. While experts emphasize that the Quad is not an Asian NATO, US officials believe it can play an important coordinating role in diplomacy; maritime security; supply-chain security; and technology design, development, governance, and use. The Quad, for example, recently set a joint goal of distributing one billion COVID-19 vaccine doses in Asia by the end of 2022. If and when that happens, such a provision of public goods would be hard for China to counter and represent a way for the United States and its partners to project leadership.

Collective efforts like these are necessary at a time when individually Asian countries are no match for Chinese power. That includes India, whose pandemic-pummeled economy, according to the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index, is expected to be 13 percent smaller in 2030 than forecast prior to the COVID-19 outbreak—the only Indo-Pacific nation to suffer such a large economic setback. Even though India will eventually surpass China in gross domestic product, due to its still-burgeoning population, that moment is decades away. The Lowy Institute characterizes Japan as “the quintessential smart power” in punching above its weight, but one that is nevertheless in decline. While others—such as Australia, Vietnam, and Taiwan—are gaining in power as measured by the index, none can hope to counter China alone. The United States still ranks as the preeminent power in the region but “registered the largest fall in relative power of any Indo–Pacific country in 2020,” according to the Lowy Institute.

In an atmosphere in which neither of the superpowers has (yet) prevailed, the region’s middle powers are better able to exert influence. While many Asian powers now appear more intent than they were in the past on countering an aggressive China, they worry that the United States will take an overly militarized approach to the endeavor. These nations would be apt to restrain Washington if the contest with Beijing heated up and risked breaking into open conflict.

10. The growing internationalization of conflict

The risk of conflict extends beyond growing Sino-US tensions. In today’s multipolar order, governments see battlefields as fertile grounds to shape balances of power, advance their economic agendas, or aid parties to the conflict that are more aligned with their national-security interests. Turkey, Russia, and Iran, for instance, are jockeying for expanded influence in such conflicts. In part because of this internationalization of intrastate conflicts, fighting is increasingly protracted, intense, and complex, to the detriment of civilians.

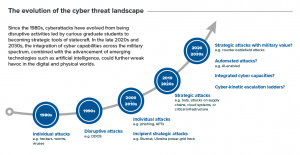

Battlefields are less traditional too. Since 2005, thirty-four states are believed to have sponsored cyber operations, with China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea thought to have instigated 77 percent of all suspected efforts. States can use cyberattacks both as an asymmetric tool to reduce a power imbalance in conventional military capabilities (e.g., North Korea), and as a symmetric one integrated across the entire spectrum of operations and domains (e.g., China). Whereas cyberattacks were previously mostly isolated incidents meant to disrupt particular systems, they are increasingly becoming a strategic tool. For example, the United States used offensive cyber operations to strike ISIS forces responsible for proselytizing, recruiting, and launching attacks.

Looking ahead, experts and policymakers alike are concerned that emerging technologies such as AI, biotechnology, and 5G, or new systems such as the Internet of Things (IoT) or cloud computing, will exacerbate Internet insecurity by revealing new vulnerabilities and providing additional tools to nefarious actors. For example, an Atlantic Council report considering alternative cyber futures mapped three potential universes: one in which cyber capabilities are mainstreamed and great-power competitors have the advantage; another in which the Internet is splintered across governmental, cultural, and business lines; and yet another in which new technologies such as AI lead to an arms race and generalized insecurity.

Three alternative worlds in 2030

Mathew Burrows is the director of Foresight at the Scowcroft Strategy Initiative and the co-director of the New American Engagement Initiative within the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Anca Agachi is an associate director at the Transatlantic Security Initiative within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.