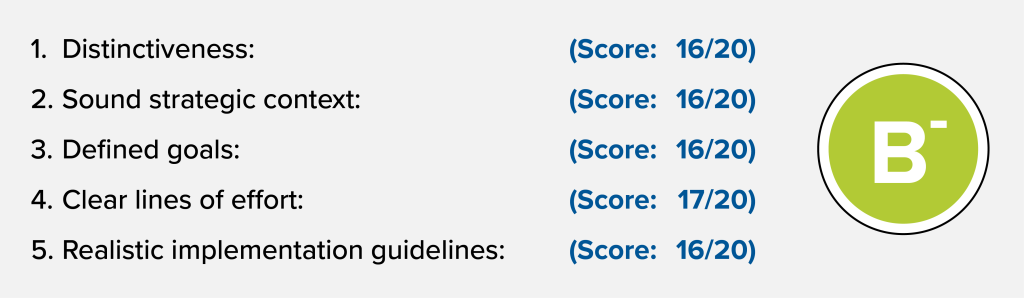

Scowcroft Strategy Scorecard:

Germany’s China strategy represents a shift in thinking, but still leaves questions

On July 13, the German government published its first comprehensive strategy on China. The purpose of the document is to lay out “the Federal Government’s views on the status of and prospects for relations with China.” The strategy frames Germany’s perception of China squarely within Europe’s three-pronged approach to Beijing in which China is characterized as “simultaneously a partner, competitor and systemic rival.” Experts with the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security read the strategy and offered their assessments of its distinctiveness and feasibility—and what it says about Germany’s positioning in an increasingly contested world.

Jörn Fleck and Leonie Müller

Jörn Fleck is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center. Leonie Müller is a young global professional with the Europe Center.

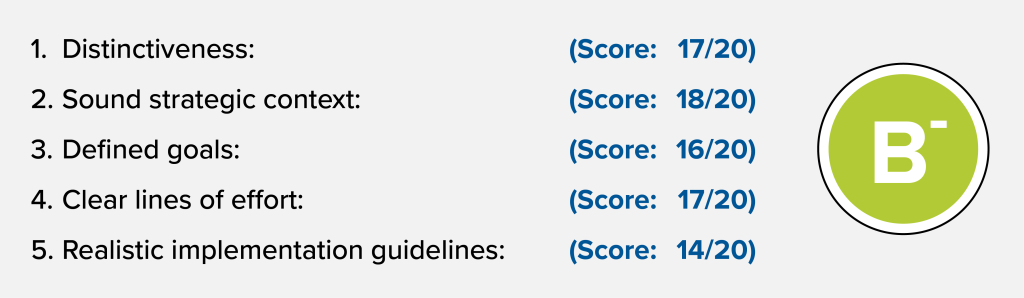

Even if Germany continues to struggle to triangulate Beijing as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival, its first ever China strategy means progress. It outlines a clear challenge to German decisionmakers, namely to adapt Germany’s approach to the realities of a changed China. Despite being short on explicitly defined strategic goals, the main themes emerging from the strategy are helpful guiding principles for further action: Focusing on the economic and technological dimensions of the China challenge that will require de-risking and diversification efforts, embedding Germany’s China policy firmly within the greater European Union (EU) approach, taking a closer look at both the challenges and vulnerabilities as well as the tools and strategies available to German policymakers, and putting in place some initial building blocks for a whole-of-government and whole-of-society response. At the same time, the attempt to balance a more forward-leaning stance without risking the economic relationship with Beijing makes for a lack of ambition, specificity, and prioritization that sells short the potential of the strategy.

Distinctiveness

Is there a clear theme, concept, or label that distinguishes this strategy from previous strategies?

Germany’s China strategy is one important milestone in the slow process of Berlin’s mental Zeitenwende, one in strategic culture and mindset. As the first of its kind for Germany, the strategy stands out not just for its novelty but also for its relative clarity, exemplified at the outset by the sober assessment that “China has changed” and so Germany “need[s] to change [its] approach to China.” One would have wished for more such simplicity from its sister product, the recently released, first-ever National Security Strategy.

Sound strategic context

Does the strategy accurately portray the current strategic context and security environment facing Germany? Is the strategy predicated on any specious assumptions?

Even if the strategy continues to try and balance the EU’s mantra of China as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival, it is more forward-leaning on the strategic challenges China poses than German policy consensus on Beijing ever seems to have been. Germany’s positioning on China is cleverly contextualized with a framework of bilateral, European, and international relations—as well as other bodies such as the United Nations (UN), World Trade Organization (WTO), and the Group of Seven (G7) and Group of Twenty (G20)—that reflect Berlin’s preferred avenues of foreign policy. A signal to both China and its European neighbors, the strategy makes a clear point of Germany channeling its policy and perspectives first and foremost through the pan-European lens and leveraging the political and economic weight of the EU as well as its trade, competition, and other regulatory tools when engaging Beijing.

Topically, it similarly covers all of the gravest risks and dependencies, importantly extending beyond merely supply chain and import chokepoints that dominate European strategic agendas. In line with the recently released EU Economic Security Strategy, this covers the green transition and global health to the cyberspace and human rights concerns all through the overall perspective of de-risking that mirrors the western security lens.

At the same time, the text does not fully reflect the strategic context that China’s aggression has created. While Berlin does not shy away from its active quest to diversify trade and investments, merely addressing “the situation in the Taiwan Strait,” neglects the reality of one of the “greatest threats” on global and regional security agendas (besides Russia’s war on Ukraine). While this balancing act between cooperation and confrontation is core to German strategy, it does not accurately relay the strategic reality that China is verging significantly more to the latter.

Defined goals

Does the strategy define clear goals?

The strategy sets out some clear aims, such as empowering the government to more effectively assert its interests vis-à-vis China, defining the tools available to Germany, and providing the basis for greater coherence and coordination among ministries in Berlin and with allies at the EU and international levels. It outlines core values and interests at the outset that form a set of guiding principles. But when it comes to developing strategic goals for Germany’s China policy, the strategy falls short. Overarching themes include a hardening of Germany’s resilience against China’s more aggressive posturing, a more proactive and comprehensive strategy of de-risking, and a very concerted effort to keep open the door to cooperation with Beijing on issues of mutual concern. But these are not translated into concretely defined goals for targeting the multitude of challenges laid out in the document.

Clear lines of effort

Does the strategy outline several major lines of effort for achieving its objectives? Will following those lines of effort attain the defined goals? Does the strategy establish a clear set of priorities, or does it present a laundry list of activities?

Even if the strategic objectives are not clearly or explicit defined, the document does identify a comprehensive set of major lines of effort where Germany and the EU will have to address the challenges China poses. Perhaps the most substantive segments on this front are those related to trade and other policy instruments at the domestic and EU levels designed to counter risks and vulnerabilities from China’s distortive economic practices. While these sections offer a realistic assessment of the challenges and the tools available to German policymakers, they often lack creativity, urgency, and depth. There is little in the way of explicit prioritization across the more than twenty-five lines of effort, which in itself is also an expression and acknowledgement of the complex whole-of-government, whole-of-economy, and whole-of-society effort that the China challenge will require. But the meatiest chapters, on Germany in the EU and international cooperation, have a heavy focus on economic relations, technology, de-risking, and diversification. This reflects the shifts that real-life German priorities vis-à-vis China are already undergoing, both in its domestic and international policymaking.

Realistic implementation guidelines

Is it feasible to implement this strategy? Are there resources available to sustain it?

Given the vast issue topics included and the vaguely defined goals, the current strategy does not instill a clear sense of how the government will go about implementation. Similar to the NSS, the China strategy misses the mark on financing, promising implementation “at no additional cost to the overall budget.” Freedom from Chinese dependencies and interference won’t come for free, and a China strategy for the world’s fourth largest economy and Europe’s largest economy ought to acknowledge that. Of course, the government has already and rightly mobilized impressive financial resources for diversification, industrial policy, and economic stabilizer efforts in response to the fall-out from Russia’s war in Ukraine. These will also come in handy when tackling the China challenge, even if they are not mentioned or matched with strategic objectives in the strategy.

On the capacity-building front, “coordinating policy and building expertise on China” will be the real metric for success, suggesting “regular meetings on China… at the level of State Secretaries” as well as a regular “report on the implementation” with Germany’s sixteen states. In the long-term, this is to be bolstered by continuously “building expertise of China” highlighting perhaps the strategies most grounding suggestions of “language skills” and “intercultural skills.”

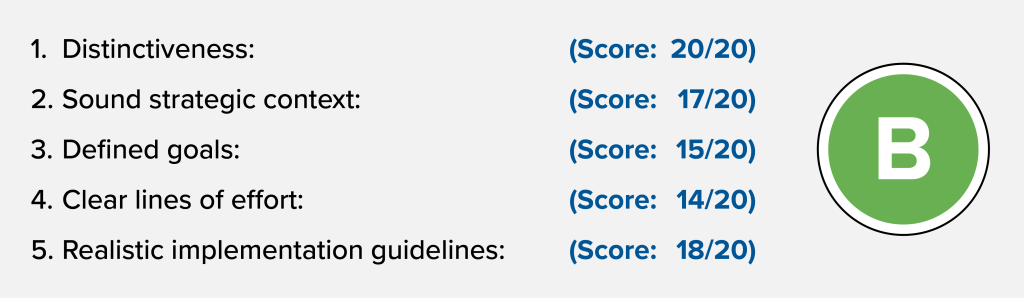

Rachel Rizzo and Katherine Schauer

Rachel Rizzo is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center. Katherine Schauer is a young global professional with the Europe Center.

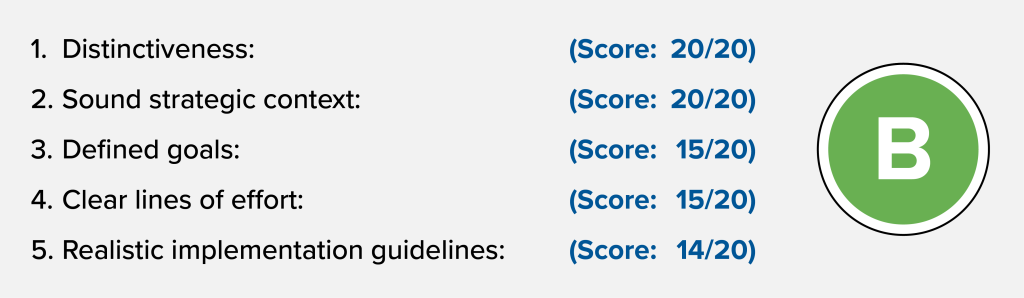

Germany’s China Strategy is notable for laying a foundation of consensus across a diverse governing coalition. The timing is also spot on; as Europe continues to build new energy partnerships after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Germany is clearly taking the lesson of overdependence to heart. That shines through in this strategy. Actual implementation, however, will be more difficult and will require further building and buy-in across both the political spectrum and everyday German citizens. According to an ECFR poll released last month, most Germans surveyed see China as a rival and adversary to their country—but a third of respondents continue to view China through the lens of a necessary partner.

Distinctiveness

Is there a clear theme, concept, or label that distinguishes this strategy from previous strategies?

During Angela Merkel’s sixteen-year chancellorship, Germany’s approach to China centered on economic cooperation and multilateral engagement. This document marks a clear shift in view from China as a partner and economic collaborator towards the triad famously adopted by the European Commission in 2019—China as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival.

Sound strategic context

Does the strategy accurately portray the current strategic context and security environment facing Germany? Is the strategy predicated on any specious assumptions?

Germany’s China strategy highlights the climate crisis as existential, and it states that the crisis cannot be addressed without the cooperation of China—both as the world’s top emitter of carbon emissions and as the biggest producer of renewable energies. The strategy also accurately reflects the need to integrate Germany’s approach with fellow EU member states on a bilateral and multilateral basis, including calls for more intensive coordination and frequent European Council discussions on this topic. The phrase “Russia’s war of aggression” is employed five times throughout the text—for comparison, “systemic rival” is referenced seven times and “de-risking” six times.

Defined goals

Does the strategy define clear goals?

As one might expect from a comprehensive strategy, the document is peppered with goals, ranging from ensuring China pursues more transparent loan agreements and tamps down on wildlife trafficking to strengthening the European economy’s “digital sphere.” The most clearly defined and actionable goals are found in chapter four, which underscores the many efforts Germany and its European neighbors must start and sustain if the region is to maintain a leading economic edge against China.

Clear lines of effort

Does the strategy outline several major lines of effort for achieving its objectives? Will following those lines of effort attain the defined goals? Does the strategy establish a clear set of priorities, or does it present a laundry list of activities?

While sometimes lost in the myriad listed priorities and goals, the strategy is broken into three “dimensions,” the most actionable lines of effort being strengthening Germany and the EU, which consists of ten focus areas. The other two dimensions—bilateral relations with China and international cooperation—are broken down into seven and eight areas of focus, respectively. Curiously, a brief, two-page section on coordination and fostering expertise on China is seemingly tacked on as a conclusion of sorts to the document, outlining in vague terms how the government will convene regular meetings at the State Secretary level on China and report on the strategy’s implementation without any timeline or concrete details.

Realistic implementation guidelines

Is it feasible to implement this strategy? Are there resources available to sustain it?

The strategy states that projects outlined within its pages are to be funded through the “relevant ministerial budgets,” and policymakers do not intend to add any additional costs to Germany’s current federal budget. While the 2024 federal budget introduced on July 5 aims to decrease spending by over 6 percent, defense spending will increase by 1.7 billion euros. With the governing coalition mindful of reemploying Germany’s “debt-brake,” ample resources to sustain the strategy will rely heavily on a sputtering economic engine.

Andrew Michta

Andrew A. Michta is a nonresident senior fellow at the Scowcroft Strategy Initiative in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and dean of the College of International and Security Studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, the US Department of Defense, or the US government.

Berlin’s new China strategy is a step forward, bringing it closer in line with the European Commission’s position, but from where I sit it is not the breakthrough for which some have hoped. There is some genuine criticism of China; for example, it highlights China’s insufficient voluntary contributions to the United Nations considering the size of its economy. It also expresses concerns about China’s military buildup and Beijing’s cooperation with Russia, but the language is quite cautious. The biggest disappointment for me is that Berlin seems to essentially leave it to its corporate sector to mitigate the risk, without providing clear guidance that speaks to national security imperatives and geopolitics. As with any such document, the real proof will be its implementation.

Distinctiveness

Is there a clear theme, concept, or label that distinguishes this strategy from previous strategies?

Yes and no—it is distinct if you apply traditional Berlin criteria of being circumspect and avoiding confrontation. In that sense, talking about China not just as “partner” and “competitor” but also a “strategic rival” is a step in the right direction. The document still underlines the federal government’s desire to cooperate with China. In addition, the “systemic rivalry” aspect is articulated largely in normative terms, without paying sufficient attention to the larger global context of strategic competition, but it does align Germany’s position more with the European Commission.

Sound strategic context

Does the strategy accurately portray the current strategic context and security environment facing Germany? Is the strategy predicated on any specious assumptions?

The strategy marks Germany’s recognition that China has been increasingly posing a threat to Berlin’s national security interests. Whether this adds up to a breakthrough will depend on what “de-risking” will mean in practice (these measures are explained in some detail in chapters four and five). I remain skeptical that “de-risking” will effectively address the continued vulnerability of Germany’s economy to China’s predatory practices. The proposed EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment is rejected but not foreclosed—the term used is “not possible at the present time,” showing usual German hedging.

Defined goals

Does the strategy define clear goals?

To a degree, the strategy defines clear goals. I am encouraged by the emphasis on security in cyberspace, resilience, and especially the repeated references to Taiwan as an important trade and investment partner.

Clear lines of effort

Does the strategy outline several major lines of effort for achieving its objectives? Will following those lines of effort attain the defined goals? Does the strategy establish a clear set of priorities, or does it present a laundry list of activities?

In some areas (like the already mentioned cyber) yes. But the overall tenor is one that offers a step forward but not a major leap. I suspect this reflects the pressure from various sectors of German industry not to damage their investment and market access in China. I suspect that is also what accounts for the delay in releasing the document and various leaks beforehand. The area for cooperation between Germany and China has shrunk somewhat, but it has not been foreclosed. One important aspect of the strategy is the clear assertion that “EU-US trade relations are of utmost importance for the German and European economies.” This signals that national security priorities are beginning to inform Berlin’s economic policy to a greater extent than previously, reflecting its recognition of the changed geostrategic environment.

Realistic implementation guidelines

Is it feasible to implement this strategy? Are there resources available to sustain it?

I hate to repeat myself, but again yes and no. There is important emphasis on infrastructure development (the Global Gateway initiative, WTO reform, UN programs, etc.) but it’s presented in terms of desiderata, not specific courses of action. For instance, the verbiage on the Global Gateway initiative is that the strategy “encourage[s]” the European Commission to implement it, but the document offers no firm steps to be taken; it talks about the desire to use the European Investment Bank, national development banks, and private funds—but how this is operationalized will be the real test.

Roderick Kefferpütz

Roderick Kefferpütz is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and the director of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union office in Brussels.

For better or for worse, the strength of the strategy lies in its novelty. Being the first ever German China strategy, it recognizes that China has changed and so must Germany’s approach to China. This is a welcome break from Berlin’s past policy. The strategy’s strength lies in a European, partners-oriented approach, identifying key challenges coming from China, especially with regard to economic competition, and an in-depth focus on economic de-risking; however, this focus comes at the expense of a more geostrategic outlook, which the weiqi strategy board cover photo of the document cannot hide. In this regard, it also doesn’t express how Germany would like to develop its relationship with China or influence Chinese behavior. It is largely a status-quo paper positioning and strengthening the German government on China—an important milestone and step forward, but more must follow.

Distinctiveness

Is there a clear theme, concept, or label that distinguishes this strategy from previous strategies?

This is the very first time that Germany has published an official “Strategy on China.” It presents the government’s views on its relations with Beijing, presents instruments to address challenges and opportunities, and provides a framework for ministries to coordinate their China-related work. The sixty-four-page strategy is also unique in its partnership-focused approach and particular European character, with the government aiming to align its China policy with that of the EU; chapter two of the strategy is entirely dedicated to the EU. This document sets a benchmark against which future German policy on China can be evaluated.

Sound strategic context

Does the strategy accurately portray the current strategic context and security environment facing Germany? Is the strategy predicated on any specious assumptions?

The strategy rightly highlights that China has changed, that the role of the Communist Party has expanded, and that China is willing to influence the global order and strive for regional hegemony in the Indo-Pacific. The economic challenge China poses to Germany (and opportunities that emerge outside of China) receive particular attention, which shows that Germany still looks at China primarily from an economic perspective. The strategy doesn’t sufficiently emphasize the broader, global systemic challenge and revisionist character of President Xi Jinping’s China and how this determines Germany’s threat environment. Particularly welcoming is the focus on China’s role in geopolitical frontiers (deep-sea, outer space, cyberspace, polar regions), the admission that deepening China-Russia ties influence the security environment, and that “developments in the Indo-Pacific can have a direct impact on Euro-Atlantic security,” highlighting that Germany is starting to take a “one-theater” approach to China.

Defined goals

Does the strategy define clear goals?

The strategy does not clearly define strategic goals with regard to Germany’s future relationship with China and China’s position in the world order. Instead, it formulates five aims, which seem relatively simple, yet are a great leap forward when considering Germany’s past approach to China. These include the aim to present the government’s views on China, enable the government to assert its values and interests more effectively, present the necessary policy instruments to achieve the strategy’s goals, provide a coherent framework for government ministries, and enhance coordination on China. The document also defines Germany’s values and interests, after which emerge a range of defensive goals, aimed at making the German economic and political system more resilient, and proactive goals focusing on engaging with partners abroad to contribute to a favorable multilateral order.

Clear lines of effort

Does the strategy outline several major lines of effort for achieving its objectives? Will following those lines of effort attain the defined goals? Does the strategy establish a clear set of priorities, or does it present a laundry list of activities?

The document is not necessarily structured in a way where it clearly identifies strategic objectives and matches them with concrete, prioritized actions. In this context, it is difficult to ascertain clear lines of effort. The strategy has six broad chapters, including “bilateral relations with China” and “strengthening Germany and the EU,” throughout which a long list of instruments and action points are listed. Economic instruments, in the context of a de-risking agenda, are also dominant in this regard.

Realistic implementation guidelines

Is it feasible to implement this strategy? Are there resources available to sustain it?

The government has committed itself to a regular report on the state of implementation as well as to an evaluation of the strategy, which will also involve the German Bundestag and other stakeholders. Germany’s budget cuts will make implementation of the strategy partially difficult. Already in the introduction, the strategy emphasizes that due to budgetary constraints, the government “will strive to implement this Strategy at no additional cost to the overall federal budget.” On the other hand, many of the action points mentioned are either already in the midst of implementation, for example on the European level, or can be done in a cost-neutral manner, such as adjusting export control lists or facilitating greater coordination within the government.

The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and its allies and partners.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship. Through cutting-edge research and high-level convening, the Europe Center’s work is conducted with the strong belief that the resilience and strength of the European Union, alongside the unity of NATO, is a critical national interest of the United States.