Scowcroft Strategy Scorecard:

Does the Quadrennial Homeland Security Review make the grade?

On April 20, the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) released the third Quadrennial Homeland Security Review (QHSR). DHS calls the QHSR its “capstone strategy document,” setting out the short- and medium-term direction for the US government’s third-largest cabinet department. By law, the QHSR is a “review,” not a “strategy,” and so it devotes much of its ninety-two pages to a summary of DHS’s current activities and recent accomplishments, more than a pure strategy would contain. With these caveats in mind, experts with the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security’s Forward Defense program read the 2023 QHSR and offered their assessment of its depth and importance for our latest scorecard.

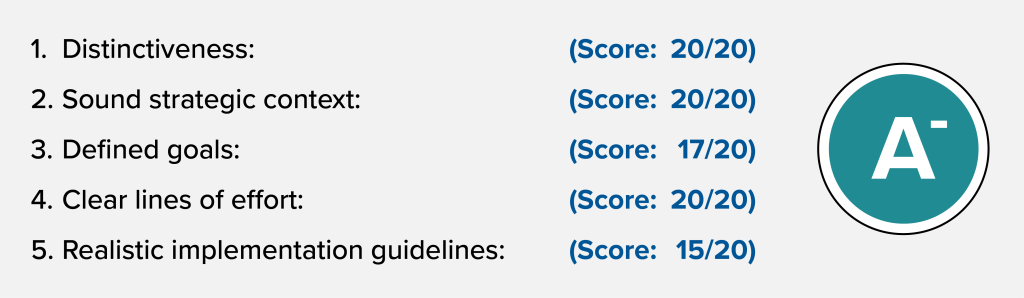

Thomas Warrick

Senior fellow, Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security; director, Future of DHS Project

Given DHS’s size and the breadth of its missions—counterterrorism; law enforcement; cybersecurity; aviation, border, and maritime security; immigration; and infrastructure protection—the QHSR should be considered one of the most important strategic documents put out by a major US cabinet department. The QHSR, while subordinate to the Biden administration’s October 2022 National Security Strategy, should, in theory, be comparable to the Department of Defense (DOD) National Defense Strategy (NDS), which gets enormous attention in Washington and around the world.

The QHSR’s reality is rather different. No major news outlet covered the QHSR’s release on April 20. Only specialized news sites and a few others reported on it or on Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas’s speech the next day announcing the QHSR’s release along with DHS’s ninety-day “sprint” focusing on US nonmilitary vulnerabilities to China and establishing a DHS task force on uses and threats from artificial intelligence.

One reason for this lack of coverage may be that the QHSR, being a “review,” is more of a summary of DHS’s current activities and recent accomplishments. Lists of accomplishments seldom make news in today’s contentious Washington political scene. While the QHSR should educate the public about what DHS does, the people who need educating the most about DHS are probably the least likely to read ninety-two pages of government prose, even with pictures. Nevertheless, the QHSR is an important strategic road map to where the Biden administration and Mayorkas want to go.

Distinctiveness

Is there a clear theme, concept, or label that distinguishes this strategy from previous strategies?

This QHSR is distinctive in three ways. First, it exists—the Trump administration did not release a QHSR during its four years between January 2017 to January 2021. While the Trump administration never produced a QHSR, it had a coherent—and divisive—approach to immigration and domestic terrorism, much of which was led from the White House, not DHS. Second, the Biden administration promised during the campaign and afterwards a break with many of the Trump administration’s homeland security policies, especially on immigration and domestic terrorism, and the QHSR makes this very clear. Third, this QHSR intentionally returns to the tone and structure of the two Obama administration QHSRs, released in 2010 and 2014, with three changes from the Obama QHSRs:

- showing how the threat landscape has changed since 2014,

- highlighting the importance of partnerships to the Biden administration’s and Mayorkas’s model of the homeland security enterprise, and

- recognizing a new mission area for DHS: combating crimes of exploitation and protecting victims.

DHS has long fought crimes of exploitation—this QHSR elevates the importance of this work and explicitly aligns DHS with the victims of such crimes. This will make it hard for future administrations to backslide from protecting exploited victims.

Sound strategic context

Does the strategy accurately portray the current strategic context and security environment facing the United States? Is the strategy predicated on any specious assumptions?

Just as the National Defense Strategy is primarily, though not exclusively, focused on military threats to the United States, the QHSR should bring equal focus and vigor on the nonmilitary threats to the United States. The third QHSR provides a good summary of today’s dynamic terrorism threats (both international and homegrown), the challenges and strains on what it calls our “broken” immigration system (Mayorkas goes so far as to call it “completely broken;” his critics would no doubt agree), cyber threats from criminals and hostile nation-states, crimes of exploitation, the threat from fentanyl and transnational organized crime, natural and man-made risks to critical infrastructure, and other challenges to homeland security. Of particular importance is elevating fentanyl, transnational organized crime, and crimes of exploitation to the strategic level—no longer are they issues of only crime. The third QHSR wants the United States to see these as strategic threats, requiring a more strategic response.

Defined goals

Does the strategy define clear goals?

A sound strategy needs to define what “victory” looks like. In DOD’s mission space, victory is understandable: the goal is victory in war, coupled with deterrence and maintaining the peace at all other times. It’s a lot harder to define the end state in homeland security, and this QHSR, like many national security strategies of previous administrations of both parties, often uses phrases like “preventing and mitigating active threats” and “continue advancing national efforts” that give the direction but leave the ultimate goal fuzzy. There are few concrete end states against which this QHSR’s success or failure can be judged, but this is not unique to this QHSR or this administration.

For example, no responsible counterterrorism strategy would publicly set itself the goal of “no successful terrorist attacks.” The difficulty of detecting lone violent extremists and their ability to get semiautomatic assault rifles, coupled with political realities in the United States, mean that the QHSR needs—rightly—to point toward other approaches like community programs (see QHSR numbered page 8) needed to reduce active shooter events well below their levels in recent years, which would be a worthy goal. In cybersecurity, the QHSR describes the many innovative programs that the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has undertaken in the past two years, but mentions only at the end of the cybersecurity section (QHSR numbered page 35) the truly transformational National Cybersecurity Strategy’s effort to shift fundamental risks from end users to the tech companies that are best situated to build security into their hardware and software. This will fundamentally change the future of cybersecurity and is a worthy goal.

Clear lines of effort

Does the strategy outline several major lines of effort for achieving its objectives? Will following those lines of effort attain the defined goals? Does the strategy establish a clear set of priorities, or does it present a laundry list of activities?

The third QHSR, like its predecessors, makes clear which DHS components are responsible for which missions and lines of effort. Unlike DOD’s military services, which encompass different domains but serve a (mostly) unified strategic mission, DHS’s eight components are organized functionally, and thus contribute differently to the QHSR’s six mission areas:

- Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) to aviation security (part of mission 1, counterterrorism and threat prevention).

- CBP, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to land border security (mission 2, border security, but also part of mission 1) and immigration (mission 3).

- The US Coast Guard (USCG) and CBP to maritime security (part of missions 1 and 2).

- CISA, ICE, TSA (for pipelines), USCG (maritime cybersecurity) and the US Secret Service (USSS) to cybersecurity and fighting cybercrime (mission 4).

- The Federal Emergency Management Agency and CISA to infrastructure protection and resilience (mission 5); however both CBP and USCG have a part of mission 5.

- ICE, CBP, USSS, and USCIS to law enforcement (mission 6, combating crimes of exploitation and protecting victims, but also part of other missions).

While this QHSR, like its predecessors (and like similar strategic summaries of DHS’s missions during the Trump administration), contains extensive descriptions of DHS activities, this QHSR proves the aphorism that—unlike DOD, where missions end when a war is over and the military pivots (for example) from the Middle East to the Indo-Pacific—at DHS, missions never go away. In this respect, the “new” mission 6 of combating crimes of exploitation and protecting victims is not at all new—it is the recognition of a mission DHS has had almost since its inception in 2003.

Realistic implementation guidelines

Is it feasible to implement this strategy? Are there resources available to sustain it?

The QHSR is not a budget, but any DHS report on its missions raises the question whether DHS has the resources to succeed in those missions. Alignment between policy and resources is one of DHS’s greatest challenges.

After the October 2022 National Defense Strategy, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin said in March 2023 that DOD’s Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 budget request was “the most strategy-driven request we’ve ever produced from the Department of Defense.” DOD is asking for $842 billion in FY 2024, $26 billion more than in FY 2023. A look at the China and Russia section of the NDS shows the link between DOD’s strategy and its budget request.

DHS cannot say the same thing about the third QHSR and DHS’s FY 2024 budget, which calls for a 1.1 percent increase over FY 2023. DHS officials understand this. The QHSR calls for more efforts and resources on cybersecurity; border and immigration security; community-based programs to prevent future mass shootings as happened in recent years in Uvalde, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and elsewhere; and to head off threats to critical infrastructure from natural causes and nation-state adversaries.

The third QHSR does not have to quantify the resources required to achieve its goals, but it has rightly laid out this secretary’s road map for where DHS and the homeland security enterprise need to do more. One of the third QHSR’s most important benefits should be to focus a much-needed debate—inside the administration and with the Congress and the American people—over whether the United States is spending enough on homeland security.

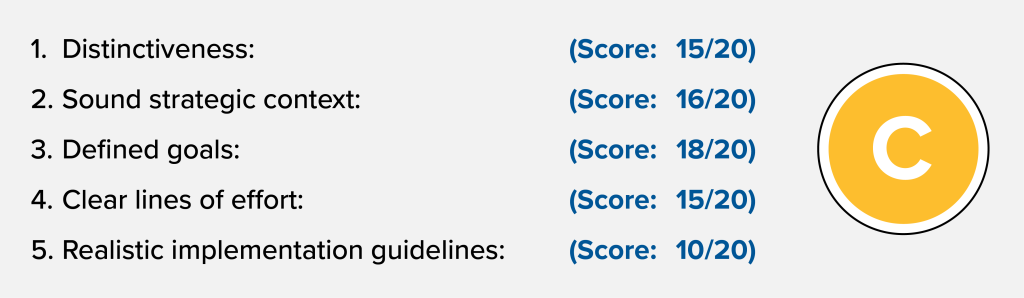

Brigadier General Francis X. Taylor (ret.)

Nonresident senior fellow, Forward Defense, Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security

Overall, DHS’s QHSR sets forth a comprehensive review of the challenges facing the homeland security enterprise. The program initiatives outlined in the report, if successful, will improve the security posture of the homeland. There are some concerns about whether there is sufficient political and popular support for the initiatives outlined in the report. In addition, DHS should consider an annual review of outcomes that have resulted from its initiatives to give US citizens a sense of how effective the department has been in improving security of the homeland. This report is a good start but needs annual reiteration that reflects sustained improvement in the United States’ overall security posture.

Distinctiveness

Is there a clear theme, concept, or label that distinguishes this strategy from previous strategies?

The QHSR sets forth in clear detail the myriad of threats that face the homeland and the challenges for the homeland security enterprise to effectively address those threats. The world continues to evolve, as does the threat environment since the creation of DHS and this QHSR reflects the complexity of the threat environment and DHS’s initiatives to address that environment in new and innovative ways.

Sound strategic context

Does the strategy accurately portray the current strategic context and security environment facing the United States? Is the strategy predicated on any specious assumptions?

The strategic context of the QHSR is sound and does not underplay the seriousness and challenges of the threat that faces the homeland security enterprise. The emphasis on partnerships to meet the challenges is an important underlying principle for DHS. Never has it been more important for DHS to strengthen and broaden its partnerships as the threat environment continues to change.

Defined goals

Does the strategy define clear goals?

The QHSR clearly defines the programs undertaken to address each mission area to address the threats that face the US homeland, but the mere implementation of programs does not ensure effective outcomes.

Clear lines of effort

Does the strategy outline several major lines of effort for achieving its objectives? Will following those lines of effort attain the defined goals? Does the strategy establish a clear set of priorities, or does it present a laundry list of activities?

There are clear lines of effort that are identified in the QHSR. The core mission areas are addressed effectively, but it is not clear that the programs initiated are yet effective in achieving the goals of DHS. Time will tell what outcomes are achieved and how effective DHS has been in mitigating the threats to the homeland.

Realistic implementation guidelines

Is it feasible to implement this strategy? Are there resources available to sustain it?

The QHSR fundamentally outlines the challenges that DHS must address to keep the homeland safe. It is not clear that there are sufficient resources to execute this mission as outlined in the QHSR. Congressional support of these initiatives and funding will be critical to DHS’s success.

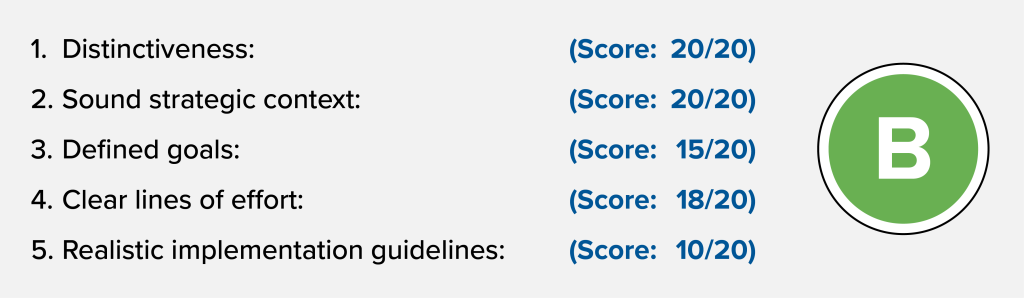

Seth Stodder

Nonresident senior fellow, Forward Defense, Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security

Like any strategy or planning document produced by a federal bureaucracy, the report on the 2023 Quadrennial Homeland Security Review inevitably provokes some trepidation from a potential reader, as such documents produced by Washington bureaucrats rarely last five seconds in an email inbox and never touch a printer.

But in all seriousness, this year’s QHSR is somewhat of a page-turner. It is the first one since 2014—almost a decade. And what a decade it has been! ISIS and Al Qaeda, while still threats, have taken a back seat to AR15-wielding white nationalist extremists in the minds of counterterrorism professionals. The sense of operational control of the border that US officials felt they had in 2010 seems like a quaint bygone era, as compared to the massive challenges the United States faces today at the US-Mexico border. The cyber threats are much more varied, with the rise of catastrophic ransomware attacks and the drumbeat of cyber threats to our critical infrastructure and our electoral system. Meanwhile, emerging technology presents opportunities and threats like nothing before—from the rising concerns about social media invasions of privacy, disinformation campaigns, and deep fakes, to the threat of quantum computing and the potentially civilization-altering challenge presented by artificial intelligence. Nation-state threats to the homeland from Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea have become far more serious since 2010. On the other hand, the ultimate challenge to the US homeland may be environmental, as the force and impact of global climate change and the likelihood of more deadly pandemics have become ever more severe.

The 2023 QHSR—and the evolving mission of DHS—aptly reflect the tectonic shifts happening in the global security environment overall and its implications for US homeland security. To be sure, the original five homeland security missions from the first QHSR Report in 2010 are still there: (1) preventing terrorism and enhancing security; (2) securing and managing US borders; (3) enforcing and administering US immigration laws; (4) safeguarding and securing cyberspace; and (5) ensuring resilience to disasters. But so many of the characters in the play have changed, or assumed greater or lesser prominence.

Suffice it to say, DHS has its hands full—with a sprawling and ever-more important set of missions, all of which requiring close partnerships with other federal, state, local, territorial, and tribal agencies, the domestic and global private sector, nongovernmental organizations, and the millions of Americans and other nationals who interact with DHS every single day. And this new QHSR ably reflects this massive and growing responsibility.

Distinctiveness

Is there a clear theme, concept, or label that distinguishes this strategy from previous strategies?

The key theme is the steadily evolving and, in some cases, radically changing and ever more complex threat picture, and the need for DHS and its components to evolve its missions and focus accordingly. This is expressed forcefully in the document. Unsurprisingly, most of the missions are the same—with one addition—as those stated in the previous QHSRs. But that does not necessarily warrant any effect on its score here as the missions of DHS and homeland security are what they are. Rather, it is the threat and broader strategic environment that has, in some cases, radically changed. And the 2023 QHSR articulates this extremely well.

Sound strategic context

Does the strategy accurately portray the current strategic context and security environment facing the United States? Is the strategy predicated on any specious assumptions?

The 2023 QHSR is extremely clear on the security environment facing the United States and, specifically, the US homeland. The QHSR also effectively nestles DHS and its six core missions neatly within the Biden administration’s broader strategic framework for the United States, as expressed in the National Security Strategy, the National Defense Strategy, and other key documents. The analysis here is sound, and it does not rest on any specious or unfounded assumptions—either about the threat or the missions and capabilities of DHS.

Defined goals

Does the strategy define clear goals?

The 2023 QHSR clearly sets forth various goals, backed up with various vignettes and descriptions of ongoing or past programs, initiatives, and other actions reflecting efforts in furtherance of goals. That said, the goals are for the most part relatively vague (e.g., “DHS must be a leader in the responsible use and adaptation of emerging technologies” or “DHS remains committed to facilitating and expanding naturalization pathways for new Americans”), without specifying any particular measurable outputs against which one might assess success or failure. However, one could argue the point of how does one know when the border is actually “secure” or under “operational control,” or when the asylum system is processing claims “fairly” or “efficiently?” And, from a fiscal standpoint, is there a way of knowing when increasing budgets hit a point of diminishing returns—where an additional dollar invested in, say, detection equipment or in efforts against drug smuggling might be better invested elsewhere, such as public health or education? It is hard to clearly find measurable goalposts for these from the QHSR.

Clear lines of effort

Does the strategy outline several major lines of effort for achieving its objectives? Will following those lines of effort attain the defined goals? Does the strategy establish a clear set of priorities, or does it present a laundry list of activities?

The QHSR—and previous DHS documents—have outlined the key missions and lines of effort, and the DHS operational components and management offices have (for the most part) worked out relatively delineated areas of focus meant to maximize unity of effort within DHS, while minimizing interagency conflict and rivalry. As is the nature of this kind of beast, the QHSR does have a bit of the whiff of a laundry list (or lists) of various component activities and success stories (albeit clean laundry, thankfully), but the lists are placed within an intelligently articulated framework of clear priorities. Again, as discussed above, it is difficult to discern measurable outputs or where the signposts are toward achieving mission goals and objectives—but the lines of effort are clearly stated.

Realistic implementation guidelines

Is it feasible to implement this strategy? Are there resources available to sustain it?

This is somewhere between an unfair question and an incomplete one—in the sense that the QHSR is not meant to be a budgetary document, and indeed there is no sense here as to whether resources are remotely adequate to achieving the goals. Moreover, as noted above, some of the goals are so vague or total (e.g., “preventing labor exploitation”), that it is hard to assess—judging solely from the QHSR—exactly how these goals might be achieved, how success or progress toward the goals could be measured, or at what point diminishing returns might be reached for additional spending. So, it’s hard to grade this one—but it surely isn’t a perfect score.

Forward Defense, housed within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, generates ideas and connects stakeholders in the defense ecosystem to promote an enduring military advantage for the United States, its allies, and partners. Our work identifies the defense strategies, capabilities, and resources the United States needs to deter and, if necessary, prevail in future conflict.

This article is part of the Future of DHS Project by the Forward Defense program with financial support from Deloitte.