Thirty years after the Dayton Accords brought peace to Bosnia, a former war correspondent investigates how a conflict that ended in 1995 still shapes warfare and world affairs in 2025.

By Thom Shanker

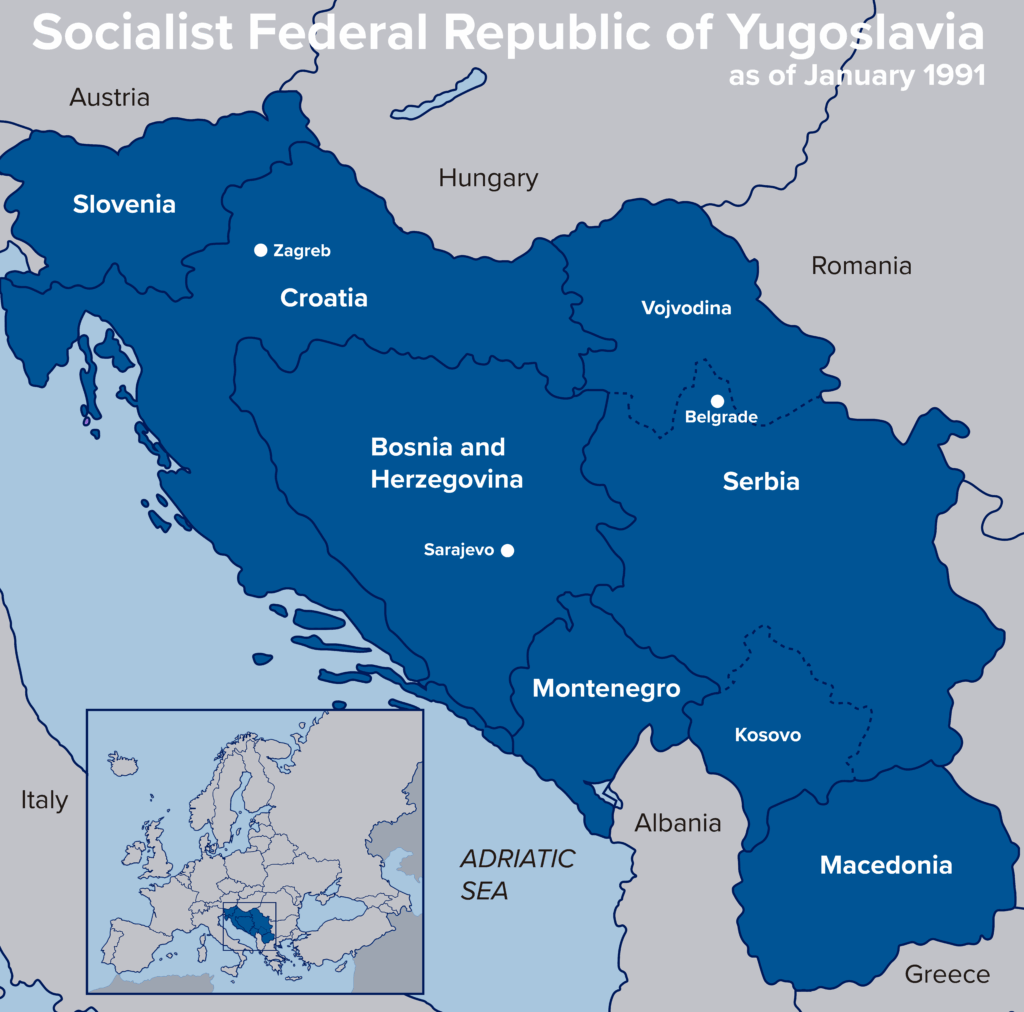

Before Vladimir Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine spawned the largest war in Europe since World War II, that grim distinction belonged to a conflict that accompanied the collapse of Yugoslavia in the 1990s—the fighting to carve up or hold onto Bosnia-Herzegovina by Eastern Orthodox Serbs, Catholic Croatians, and Muslim Bosniaks. In Bosnia, less than fifty years after the horror of the Nazi “final solution,” genocide returned to Europe.

The Bosnian war was fought with medieval tactics and twentieth-century weapons. Its signatures were siege, mass expulsion, the burning of villages and leveling of houses of worship, and mass rape and mass murder. The carnage ended thirty years ago this week, on December 14, 1995, with the signing of the US-brokered Dayton Accords.

The Balkans produce more history than can be consumed, goes the aphorism usually attributed to Winston Churchill, and that is true of the Bosnian war. Yet too many in the United States and around the world—though certainly not in the Balkans—have consigned the conflict to history or forgotten about it entirely.

Several decades on, the war’s consequences and lessons still have influence and resonance in many areas of modern warfare, including conflict diplomacy, intelligence gathering, war reporting, humanitarian relief missions, justice for war criminals, and the application of military power. In some instances, the Bosnian war has had concrete, lasting impact on more recent conflicts. In others, the war has offered relevant lessons that have nevertheless gone unheeded.

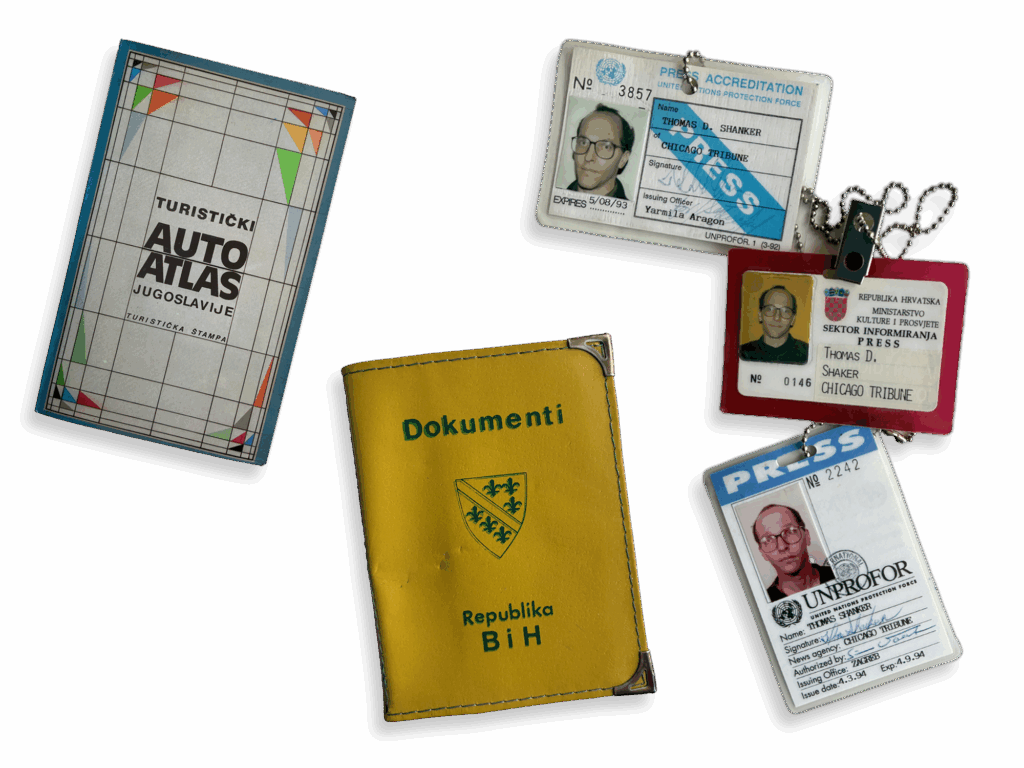

In reflecting on my nearly three years covering the Bosnian conflict for The Chicago Tribune, and the ways in which it has stayed with me in the three decades since, I have concluded that when you go off to cover a war, the war covers you. That is true not just for the journalists who risked all to witness and report on the conflict, but also for those who worked to provide assistance to civilians at risk, negotiate a peace plan, enforce an eventual cease-fire, and bring some measure of justice to the region when the guns finally fell silent. And it is true for all of us—even those with no firsthand experience of the conflict—in ways that should be more fully appreciated.

Conflict diplomacy

Militaries do not win wars. Militaries set the conditions—or, more often, impose the conditions—under which governments and their representatives end wars.

That is the conclusion of an American diplomat who played a pivotal role in ending the fighting in Bosnia—Christopher Hill, who served as a deputy to the late Richard Holbrooke, chief architect of the Dayton Accords.

“People felt that it was our willingness to use force that ultimately was the success at Dayton,” Hill told me, referring to the punishing bombing campaign, Operation Deliberate Force, that NATO carried out on Bosnian Serb targets in late summer 1995 after Bosnian Serb troops massacred eight thousand Muslims of fighting age around the town of Srebrenica. “There’s no question that we used force—but force was in support of diplomacy. It wasn’t the other way around.”

Hill, whose résumé includes posts as US ambassador to Serbia, the Republic of Macedonia, Iraq, South Korea, and Poland, and special envoy to Kosovo, identified a key element beyond military power that forced signatures on the peace plan from leaders of three warring republics—Slobodan Milosevic of Serbia, Alija Izetbegovic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Franjo Tudjman of Croatia. (The leadership of the self-declared Republika Srpska inside Bosnia were deliberately excluded.)

“We ended the war on terms that left no one terribly happy—but everyone got something from it,” Hill said. “We ended it in a way where we understood the equities on all sides. We did not try to create a situation where someone is a total loser and someone is a total winner, because that is just a recipe for more war.”

Hill credited Holbrooke as an example of how sometimes a strong, even overbearing, individual is needed to knock heads of autocratic bullies. The strategy of strong-arm negotiations under pressure of military punishment proved, Hill said, “that American diplomacy is not an oxymoron.”

Hill, who is now a distinguished fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center, grew pensive when assessing why the slaughter in Bosnia was allowed to continue for more than three years before decisive Western action. “Yes, it took a while, obviously, for people to understand that this situation, Bosnia, was making a mockery of a ‘Europe whole and free,’ and at peace. It took a while to realize that if we—the US and our European allies—pulled together instead of finger-pointing, we could get something done. And it ultimately succeeded in halting the killing.”

Underscoring the enduring value of the Atlantic alliance, Hill argued that “relationships between nations extend your reach, rather than inhibit your reach.” At the time of the Bosnian war, he added, “we had trust issues with some countries. But I’ve never seen it like it is today. If we can rebuild trust and a sense that, ‘together, we can do more,’ we can go further.”

The Bosnian war also was a defining moment for Europe. The initial response from European powers when war broke out on their continent in the 1990s was mostly hands-off. Then the Europe-backed United Nations Protection Force that did respond was handcuffed by insufficient personnel, the absence of effective weapons deployments, and rules of engagement distributed across so many capitals that it weighted the power of “no.” But out of that experience—of European capitals standing by powerlessly and watching Washington halt slaughter in Europe’s southeastern corner—came the roots of the still-evolving European common defense, foreign, and security policy, as well as Europe’s efforts to play a much stronger role in helping defend Ukraine than it did in protecting the victims of aggression in Bosnia.

Hill identified another essential ingredient in the success at Dayton in ending the war: “The intelligence was really good. We understood what the Serbs were after. By the way, I didn’t feel that way when I was in Iraq, nor did I feel that way when I was dealing with the North Koreans. But on Bosnia, the intel people really had it right.”

Intelligence gathering

The American intelligence community saw it coming.

A year before fighting broke out in Croatia, and two years before the far bloodier and longer war in Bosnia began, a detailed National Intelligence Estimate predicted with stunning accuracy that Yugoslavia—once a multi-ethnic, multi-religious, peaceful, nonaligned communist country with a standard of living far above its Soviet-bloc neighbors—would convulse with violence: Serbian Eastern Orthodox versus Croatian Catholic versus Bosnian Muslim.

“Yugoslavia will cease to function as a federal state within one year, and will probably dissolve within two,” the National Intelligence Estimate, titled Yugoslavia Transformed, declared—a timeline that proved correct. The report’s only significant error was one of sequencing, as it predicted that violence would most likely start in Serbia’s Muslim region of Kosovo; the Kosovo war did not begin until 1998, after fighting in Croatia ignited in 1991 and in Bosnia in 1992.

Diplomats had been withdrawn, and the United Nations Protection Force proved unable to protect Bosnians, its own troops, or anybody else.

The report, stamped SECRET when it was completed on October 18, 1990, was declassified in 2006, and it now offers a lesson of what good intelligence looks like—even if its assessments did not inspire action by American and Western European leaders, who were hoping to reap the benefits of a peace dividend after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

After all, many Americans could not find Bosnia on a map and did not grasp its importance. US leaders incurred no political cost in looking the other way, certainly not in the early years of the war. The US-led NATO bombing and muscular diplomacy leading to Dayton only occurred after Bosnian Serbs cuffed and humiliated Dutch peacekeepers, and the discovery of the Srebrenica massacre.

The National Intelligence Estimate contained this prophecy: “The most plausible scenario for interrepublic violence is one in which Serbia, assisted by disaffected Serbian minorities in the other republics, moves to reincorporate disputed territory into a greater Serbia, with attendant and bloody shifts in population.”

The report also predicted, correctly, that Serbia would inherit the bulk of the armor and other weapons of the Yugoslav National Army when the central government dissolved, and would cite protection of fellow Serbs in neighboring republics as an excuse to turn those guns on Croatia and Bosnia to carve out a Greater Serbia. (In Croatia, people tended to live in communities that were mostly segregated, and war there was shorter. In Bosnia, as an accidental result of history, the different communities were intermingled.)

The National Intelligence Estimate assessed that a system designed to turn nonaligned Yugoslavia into a porcupine in the event of invasion from the west or the east—the creation of local militias, with command-and-control and plentiful small arms—would allow each minority group to take up arms against the others. That is precisely what happened.

The intelligence in advance of the war in Bosnia contrasts sharply with the community’s work on weapons of mass destruction held by Saddam Hussein, which was used by President George W. Bush to make a case—falsely—for invading Iraq a decade later, in 2003.

Yet three decades after the war in Bosnia and two decades after the invasion of Iraq, in the weeks before Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the intelligence community again showed what getting it right looks like—and, this time, how good intelligence could be put to good use in advance of conflict erupting. The CIA director at the time, William Burns, was a veteran diplomat who had served as ambassador to Moscow, and who often said that his insights into gathering and assessing intelligence stemmed from his decades as a consumer of intelligence at the State Department. With a diplomat’s sense for what it would take to rally a coalition to counter the Kremlin, he declassified and shared intelligence—with Ukraine, with European allies, and with the US media—predicting a Russian invasion. The world was warned, again. But, in an echo of what transpired in Bosnia, too few accepted the truth about Putin’s imminent intentions for Ukraine until blood was shed.

War reporting

Bosnia was a war crime masquerading as a war.

That dawned on Roy Gutman, who covered the conflict for Long Island’s Newsday newspaper. Like so many others in the band of brothers and sisters who took immense risks to relay the tragedy in Bosnia to the world, he devoted much of his time to tracking artillery, mortars, and troop movements. (As ever, since Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, scribes chase the sound of fighting.)

“That fighting was right in front of you,” Gutman told me. “Bosnian Serbs were doing normal military operations in some ways, like the siege of Sarajevo—but the real action was deep in the provinces, far from the cameras, where they were cleansing the population by using methods of terror—war crimes.”

Gutman was the first to widely publicize the Bosnian Serbs’ chain of concentration camps in Bosnia, where the mostly Muslim detainees were deposited after transport by bus, by forced march, or in cattle cars to be tortured and murdered. He wrote about the Serb campaign of systematic mass rape of Muslim girls and women and documented the destruction of mosques.

“I decided that was going to be my coverage, not just the bang-bang,” Gutman said. “I was going to cover the expulsions, the deportation of the populations—but looking carefully for examples where you can prove that the government is involved and responsible.” Gutman received the 1993 Pulitzer Prize in international reporting for “his courageous and persistent reporting that disclosed atrocities and other human rights violations in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina.” (He shared the prize that year with John Burns of The New York Times, who put the Bosnian war on the map for global readers with his heartfelt stories documenting the siege of Sarajevo and the destruction of what once had been an Olympic city and a multicultural gem.)

In earlier conflicts, the press often traveled with military units, and could hope for assistance in emergencies from those forces or their embassy. Not in Bosnia. Diplomats had been withdrawn, and the United Nations Protection Force proved unable to protect Bosnians, its own troops, or anybody else.

The Bosnian conflict accelerated a trend of war reporting becoming increasingly dangerous. Journalists were targeted by snipers, mortars, and artillery, and getting the story often required traversing a series of roadblocks and checkpoints guarded by angry men with guns.

Every time I crossed into Bosnia, I brought a flak jacket with ballistic plates on the front and back (and my name and blood type stenciled on the front), a helmet, food, and a sleeping bag—and made sure that I had filled two five-gallon canisters of fuel in the trunk of my vehicle. Larger news organizations provided their reporters with armored cars and satellite phones. Also required were supplies of Marlboros, Deutsche marks, and whiskey—to bribe your way past Serb militia checkpoints. (After the Tribune’s accounting department initially kicked back my receipts—“We don’t pay for your booze and tobacco”—I created a new category called General Reporting Expenses. One colleague filed his receipts for checkpoint bribes as “chemische Reinigung,” German for dry cleaning.)

To move people out of Sarajevo … we had to sometimes cross, literally, more than thirty checkpoints staffed by different militias, all armed and all ready to shoot.

—Amir Shaviv

Getting to the story also required creativity. Early in the war, when Bosniak refugees reached safety and told of a new and vicious cycle of ethnic cleansing in the east of the republic, Serb forces on the Serbian side of the Drina River shut the border, obviously to assist their Bosnian Serb mates in continuing the violence with no outside witnesses.

At the time a group of us were working with a brilliant interpreter and “fixer,” a local journalist who was enterprising and courageous to the point that we fondly nicknamed her “Mad Alex.” Alex and I once made an appointment at the Bosnian Serb legation in Belgrade. While we were kept waiting in the reception area, we managed to lift a dozen sheets of formal Republika Srpska letterhead. We forged official-looking papers conferring the right to pass first the Serb and then the Bosnian Serb checkpoints on both banks of the Drina. (Think “letters of transit” in the film Casablanca.) Over several days, our band of reporters was the first to document a well-organized offensive to force the expulsion of thousands of Muslims from eastern Bosnia—a brutal ethnic-cleansing campaign accompanied by the looting and torching of their villages, and the toppling of the minarets of their mosques.

Attempts to prevent reporters from witnessing atrocities “is what drew me to Syria later,” Gutman said. “I just saw Bosnia all over again—where all the operations of the war were war crimes. But [Bashar al-Assad] learned the lesson of Bosnia: Don’t let in the media.”

And Putin has learned that lesson too. “On the Ukrainian side of the war, reporters have what looks like almost total freedom, and are doing a really fine job of on-the-ground war reporting,” Gutman said. “How many can go to the Russian side of the lines?”

Humanitarian relief

The fragmentation of Bosnia along ethnic and religious lines challenged the efforts of international relief organizations to an extent that they had rarely faced before—challenges intensified by the large scale and long duration of the conflict.

Many previous relief efforts around the world had followed a model of bringing aid to people in need on one side or the other of identifiable frontlines.

Before Bosnia, large-scale humanitarian aid missions were mostly “dancing with one devil,” said Amir Shaviv of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, or JDC, a relief organization founded in the shadow of World War I.

Instead of negotiating with a single aggressor to funnel relief to a population in need, aid organizations in Bosnia were forced to negotiate with numerous ethnic militias and rogue warlords to deliver help across a terrain contested by three factions, with large Muslim populations pushed from villages across swaths of Bosnia and locked mostly inside the besieged areas of Sarajevo, Srebrenica, Gorazde, Zepa, and Bihac.

Shaviv’s title during the three years of the Bosnia relief effort said it all: assistant executive vice-president for special operations of the Joint Distribution Committee—a military-sounding title that reflected the need for strict command-and-control, discretion to the point of secrecy, and negotiations with a criminal lineup of local militia captains.

“To move people out of Sarajevo and to bring them to safety in Croatia, we had to sometimes cross, literally, more than thirty checkpoints staffed by different militias, all armed and all ready to shoot,” Shaviv recalled when we spoke. “Some wanted money. Others wanted medications, which we happily gave them. Often, a case of whiskey settled it.”

Over the course of the war, JDC evacuated about 2,500 people from besieged Sarajevo. Women, children, and the elderly. Muslims, Christians, and Jews. All of the evacuations, he said, “were accomplished without a single injury or death.”

Many humanitarian aid groups did heroic work in Bosnia. But those identified with one faction or another risked failure at checkpoints operated by a rival group. What was JDC’s secret for success, even as the efforts of other, larger relief organizations were sometimes stymied?

“JDC operated in a nonsectarian, nonpolitical way,” he said. “When we brought food in, they cooked for Jews, Muslims, Christians, anybody. When we took people out, it was also the same thing—same with medicines.”

JDC even established a wireless radio connection after the Sarajevo phone system was destroyed by Serb artillery. Time slots for communicating outside the siege zone were allotted to the range of Sarajevo’s diverse residents.

Shaviv said that one of the Bosnian war’s lessons for today is that relief missions must be designed with stamina and resilience, since contemporary armed conflict seems never-ending and tends to feature complex webs of combatants. There are “no longer ‘slam dunk’ rescue operations” in which “you deal with a regime, execute a swift operation, get your people out—and celebrate,” Shaviv noted.

International law

Rape, enslavement, and the torching of entire villages by invading armies are tactics as old as human history. In the time of the Ancient Greeks, military commanders prayed to their gods atop Olympus for guidance on how to adjudicate whether people, property, and titles were fitting spoils of war. More recently, mortals have tried to legislate against and sit in judgment of war crimes, with varying effectiveness.

The war in Bosnia increased understanding and scrutiny of war crimes and conduct of aggressors. In subsequent conflicts—from Myanmar and Ukraine to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and South Sudan—military acts of mass murder, mass rape, and ethnic cleansing have been identified for what they are: not an expected if horrific part of the battlefield, with spoils going to the victor, but illegal actions that deserve the world’s attention and legal penalties. The term “ethnic cleansing” itself—now a core part of the world’s lexicon for conflict—is a product of the Bosnian war, stemming from the Serbo-Croatian phrase etnicko ciscenje.

“The Bosnia conflict made war crimes as a concept an important part of the global vernacular,” said Diane Orentlicher, a professor of international law at American University who specializes in war crimes tribunals. “The phenomenon is hardly new, but attention to war crimes used to be largely the province of human rights organizations and military lawyers. As a result of the Bosnia conflict, I think awareness of war crimes was globalized.” Orentlicher is the author of Some Kind of Justice: The ICTY’s Impact in Bosnia and Serbia, the definitive account of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia as it sought to hold political and military leaders accountable for war crimes.

Until the conclusion of its final case in 2017, the UN-established International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia worked to prosecute those responsible for crimes committed during the Yugoslav wars, including Bosnia’s. (Data courtesy of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia)

The UN Security Council established the tribunal in May 1993 with a mandate to prosecute “those responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the former Yugoslavia since 1991 and thus contribute to the restoration and maintenance of peace in the region.” The court delivered justice to victims of the Balkans wars by bringing to trial and convicting ninety-three people—Bosniak, Croat, and Serb—including Radovan Karadzic, the political leader of the Bosnian Serbs, and Ratko Mladic, the Bosnian Serb military commander. Both are serving life sentences. The mastermind of the wars across the former Yugoslavia, Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic, also was brought to trial at The Hague on charges including genocide, but he died before a verdict was handed down.

While she acknowledges that the court was flawed, Orentlicher said its impact on efforts to deliver justice (however imperfect) after peace (however fragile) continues today.

“The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia was the template that provided guidance for all subsequent international and hybrid tribunals, both in a positive and negative way,” she said. “For all its achievements, it wasn’t a perfect tribunal, and tribunals created since then have tried to improve on its example by, for example, enhancing victims’ participation in their work.”

The tribunal raised awareness about specific war crimes, especially the use of sexual violence as a tool of combat.*

“When there were reports of mass rapes in Bosnia, before the ICTY was even created, a global women’s rights movement demanded that these atrocities be prosecuted as war crimes, and their advocacy helped create momentum to create the Yugoslavia tribunal itself,” she added. “So the Bosnia conflict brought unprecedented attention to the issue and helped galvanize global efforts to combat sexual violence in war.”

Military power

With war in Ukraine now overshadowing the Bosnian war as Europe’s largest conflict since 1945, no lessons of the Balkans bloodshed are as relevant today as those on the smart application of military power—when to use it, how much to use, and how to do so with a clear eye on the adversary’s pressure points.

General Wesley Clark was the US Defense Department’s representative to the US negotiating team for Bosnia, and he was by Holbrooke’s side for treacherous trips into and out of Sarajevo and throughout the Dayton peace talks. He returned to the continent in 1997 with one of the military’s most prized assignments: NATO’s supreme allied commander, Europe. In 1999, he oversaw Operation Allied Force, the bombing campaign to punish Milosevic’s Serbia for its cleansing of ethnic Albanians in the province of Kosovo—in some ways, unfinished business from the Bosnian war.

Clark, who is now a member of the Atlantic Council’s Board of Directors, recalled that following the Dayton Accords, NATO deployed a US-led Implementation Force (or IFOR) into Bosnia that, unlike previous United Nations efforts, went in with armaments that clearly overmatched those of the three warring parties—and, just as importantly, with clear approvals for punishing violators of the peace deal.

“We gave the military more or less unlimited authorization in Bosnia,” Clark said. “We gave the military commander what was essentially a silver-bullet capacity so he could intervene at any time on any issue in any manner he chose. This was necessary to assure that we had US congressional support for the troops that went in—but it was also a powerful warning to the warring factions: No more messing around.”

A forgotten footnote of the IFOR mission was how clearly Serbians, Croatians, and Bosniaks heard the message. Not a single American combat death occurred during the peacekeeping—really peace-enforcement—mission.

We gave the military more or less unlimited authorization in Bosnia … [the US commander] could intervene at any time on any issue in any manner he chose.

—General Wesley Clark

Assessing the war in Ukraine in light of the lessons of Bosnia, Clark argues that the still-tentative proposals for deploying forces to support any armistice in the country should approach a peacekeeping mission with all of the tools required for a warfighting mission in order to deter further aggression. And those forces have to be forward-deployed at whatever border between Ukraine and Russia is set by an agreement, and with clear authorities to deal forcefully with cease-fire violations.

And just as the Dayton Accords required the assent of Serbia’s strongman Milosevic, peace in Ukraine is dependent on one person: Putin.

“The reason Dayton worked was because the Serbs wanted a deal,” Clark said. “Milosevic realized he had reached the end of the line, militarily, in Bosnia.”

In contrast, Putin has not reached that point. “The lesson of Bosnia is that you’re not going to be able to bring the war in Ukraine to an end until Putin thinks he’s losing,” Clark said. “And Putin does not think he’s losing, and right now sees no reason to think he is going to lose.”

What finally brought the vile war in Bosnia to a conclusion was a form of American idealism personified in Holbrooke, “a man who believed passionately in America’s power to do good in the world and to spread—it seems almost quaint today to talk about them—American values.”

That assessment came from Roger Cohen of The New York Times, speaking at an Atlantic Council panel convened by the Adrienne Arsht National Security Resilience Initiative to reflect on risks to journalists and diplomats thirty years after the negotiations in Dayton ended the slaughter.

The horrors of the war drove Holbrooke to Dayton. But so too did values: freedom, democracy, the right of peoples to govern themselves, the sanctity of borders, and the rule of law.

Holbrooke “wanted very much, and fought very hard, to bring that to Bosnia,” Cohen said.

“And if we forget those values, if we lose sight of those values, if we allow those values to be trampled in a way that they die,” Cohen warned, “then I think that will be at once a terrible thing for the world, and a very dangerous one.”

*This sentence was updated December 22 to clarify wording related to the legal definitions of genocide and sexual violence as a tool of combat.

about the author

Thom Shanker covered the war in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995 for The Chicago Tribune, before joining The New York Times as a national security reporter and editor. He directs the Project for Media and National Security at George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs, and is a nonresident senior fellow at the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security at the Atlantic Council.

Related content

Explore the programs

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world.

Video footage of Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, filmed May 19, 1994, courtesy of Reuters.