On February 16, the same day it almost approved no confidence in the government, Ukraine’s parliament successfully passed law #3700 on its eighteenth attempt. While the law was overshadowed by the controversy over the vote on the government, the legislation is the equivalent of a new “January 16th law” for Ukrainian politicians.

On February 16, the same day it almost approved no confidence in the government, Ukraine’s parliament successfully passed law #3700 on its eighteenth attempt. While the law was overshadowed by the controversy over the vote on the government, the legislation is the equivalent of a new “January 16th law” for Ukrainian politicians.

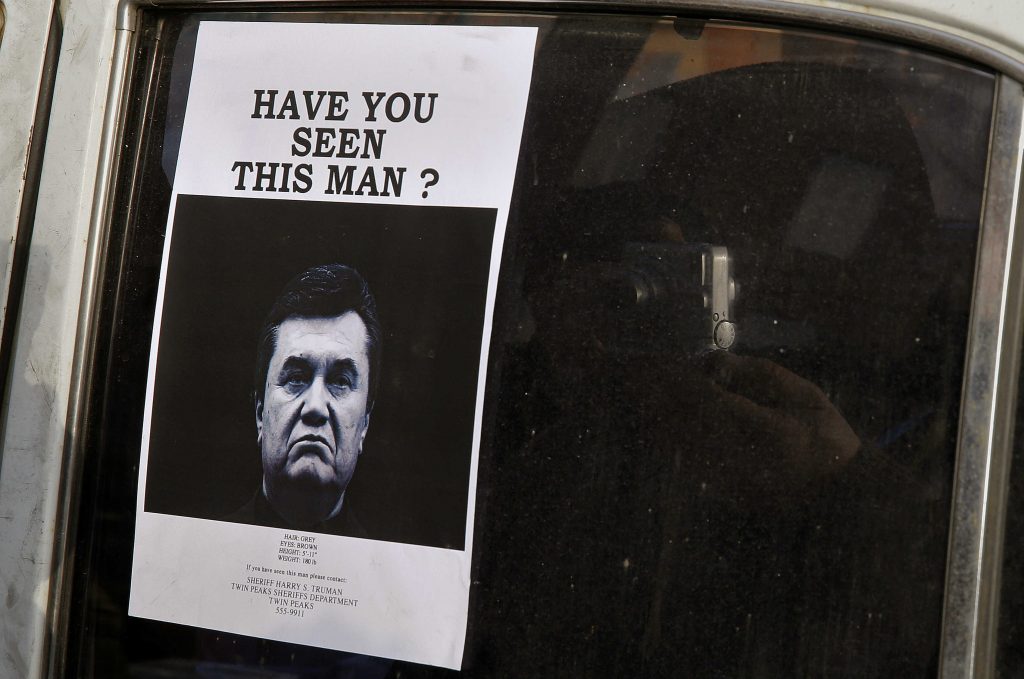

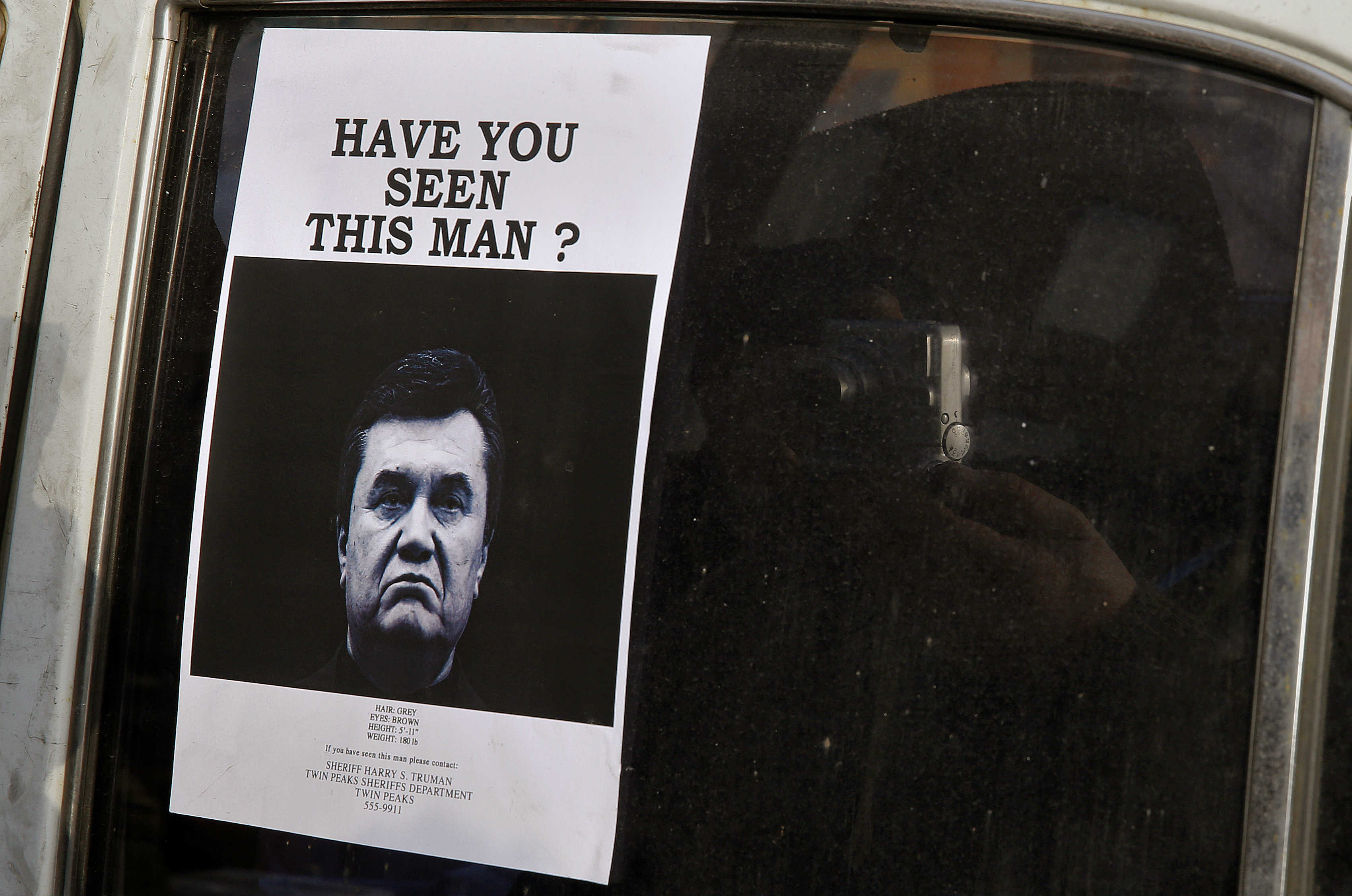

What is a January 16th law? As the Euromaidan protests gathered momentum on January 16, 2014, President Viktor Yanukovych’s parliament passed laws that severely restricted free speech, assembly, and other human rights. The infamous law was among the first to be repealed following the impeachment of Yanukovych a month later.

Parliament’s new law restricts free speech and undermines the will of Ukrainian voters, as it allows the expulsion of deputy candidates from party lists on the proportional ballot. Granted, it affects only candidates for deputies and not the entire population, as did Yanukovych’s January 16 law, but the effect is chilling. No longer do voters decide who is elected from the party lists. Instead, political party bosses have the unilateral and unchecked power to remove those candidates they don’t like. Voters may elect a candidate in a free and fair election, but if that candidate doesn’t obey every demand of the party bosses, he or she can be removed and replaced with a more pliant candidate down the list.

For example, voters may overwhelmingly elect Mr. Shevchenko from the “passing part” of the list (the candidates near the top with a realistic chance of being elected), but party bosses prefer Mr. Ivanov, who is farther down the party list. Therefore, after the election—but before the swearing in of the new deputy—party bosses can remove Shevchenko from their list and install Ivanov instead. Voters (and Mr. Shevchenko) have absolutely zero recourse. This new law gives a handful of party bosses a monopoly to sell spots on the party list to the highest bidder. Thus, voters’ will becomes a mere suggestion, rather than the sovereign choice of the electorate.

On February 25, President Petro Poroshenko signed the bill into law. There is a specific reason for this. When an MP gives up his or her mandate (to take a post in the government, for example), he or she is replaced by the next candidate on the respective party list. With a cabinet reshuffle currently in the works, several MPs could end up in the government and be required to relinquish their parliamentary mandates. With this in mind, the Poroshenko Bloc sobered up to the reality that the next candidate on their list for parliament is Andriy Bohdan, the chief lawyer for Gennadiy Korban, who is an ally of oligarch Ihor Kolomoyski and serves as Ukrop Party chairman. At the time the list was agreed upon in the fall of 2014, Kolomoyskyi was serving as governor of Dnipropetrovsk, and his relationship with the President was manageable. However, since Poroshenko fired Kolomoyskyi last spring, he has been opposed to any Kolomoyskyi ally getting into parliament—especially from his own party list.

But should the will of the voters be voided simply because the Poroshenko Bloc didn’t properly vet its own candidates? In the United States, when an elected official switches parties, he or she remains in office for the duration of the term and has the same opportunity to seek reelection with the new party. That is because voters’ will is sovereign, and supersedes the wishes of political party bosses.

By signing law #3700, Poroshenko has lost credibility in talking about electoral reform. It was Poroshenko, after all, who pushed for an “open list” system, which supposedly would eliminate such political intrigues and restore power to the voters. However, the open list system that was implemented was not open, but rather a poor imitation of a similar law once used in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Poroshenko was not the only backer. Cosponsors of the legislation include Yulia Tymoshenko with Fatherland, Poroshenko Bloc Deputy Faction Leader Yuri Lutsenko, Radical Party Head Oleg Lyashko, Samopomich Faction Head Oleg Berezyuk, and People’s Front Faction Head Maksim Burbak.

It is no surprise that Tymoshenko was a key booster of the new law. It was she, together with Yanukovych, who implemented the infamous “imperative mandate” in 2006, which curtailed the mandates of members of parliament who left the faction, and replaced them with firmly obedient candidates. The imperative mandate enforced strict party line votes, as the threat of expulsion from the faction and subsequent loss of their mandate loomed over each deputy. In effect, the imperative mandate gave the political party, and not the voters, power to decide who holds each seat.

Law #3700 is merely an updated version of the old imperative mandate. As for the Poroshenko Bloc and Samopomich, their faction leaders’ motivations in supporting this law are to prevent the defection of any additional MPs from their respective factions (fifteen have left the Poroshenko faction already, and six have been lost by Samopomich). But regardless of the motivations, the law is now law of the land, unless at least forty-five MPs challenge it in Constitutional Court. Meanwhile, it is a setback for Ukraine’s democratic development and represents a creeping return to Yanukovych’s January 16th laws.

Brian Mefford is a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center. He is a business and political consultant who is based in Kyiv, Ukraine. This article has been adapted from Brian Mefford’s blog.

Image: A man takes photos of a "Wanted" notice, of fugitive former Ukrainian President Victor Yanukovych, plastered on the window of a car used as barricade near Kyiv's Independence Square February 24, 2014. REUTERS/Yannis Behrakis