Four years ago, Lebanon’s north-eastern borderlands with Syria came to the forefront of media attention as the entry point for Hezbollah fighters to participate in the battle to capture the key Homs countryside town of al-Qusayr from Syrian rebels. Though there had already been reports of Hezbollah ‘martyrs’ through fighting in Syria, al-Qusayr was the first major engagement in the Syrian civil war in which Hezbollah’s role became widely publicised, not unjustified considering that the group lost dozens of fighters in the battle.

Four years ago, Lebanon’s north-eastern borderlands with Syria came to the forefront of media attention as the entry point for Hezbollah fighters to participate in the battle to capture the key Homs countryside town of al-Qusayr from Syrian rebels. Though there had already been reports of Hezbollah ‘martyrs’ through fighting in Syria, al-Qusayr was the first major engagement in the Syrian civil war in which Hezbollah’s role became widely publicised, not unjustified considering that the group lost dozens of fighters in the battle.

Hezbollah has partly justified its intervention in Syria on the grounds of protecting Lebanon’s borders as well as Lebanese citizens. In the case of the border areas of the northern Beqaa and the Homs countryside, there is a basis of reality to these ideas. While some Syrian regime border guard checkpoints exist, there is still no border fence here, and there are in fact thousands of people of Lebanese nationality who have been living on the Syrian side of the border since well before the Syrian civil war. These Lebanese people resident in Homs countryside border villages like Zeita are mostly Shi’a and related to their compatriots on the Lebanese side of the border.

| Looking out towards the Homs countryside. Photo author’s own. |

Politically, these northern Beqaa border areas are unsurprisingly dominated by Hezbollah, with a minority supporting the Amal movement that is ideologically loyal to Imam Musa al-Sadr. A visit by an outsider to these areas will almost certainly lead to an inquiry from a Hezbollah security official. At the same time, one must remember the importance of the clan basis of society here. Some of the clans of note include:

- Ja’afar

- al-Jamal

- Nasr al-Din

- Qataya

I have been to the Lebanese village of al-Qasr on the border with Syria at the invitation of members of the Ja’afar clan. The atmosphere in the area is generally quiet and daily life mostly proceeds as normal. Some tents housing Syrian refugees can be found, while Syrians and Lebanese traverse both sides of the border on a daily basis. Though Syrians coming to Lebanon now officially require a visa, some leeway is granted in this area: for instance, some Syrians come to al-Qasr to sell bread at lower prices than purchased from Lebanese vendors. Some residents of al-Qasr might go to Syria for the day to buy food products for the similar reason of lower prices.

| Amal Movement posters and banners in al-Qasr. Only a minority of people here support the organization though. Photo author’s own. |

To be sure, there is general concern about ‘spillover’ from Syria in the form of terrorist attacks. Last summer, multiple suicide bombings struck the Christian village of al-Qaa to the east of al-Qasr. Further to the southeast in the Jaroud Arsal-Qalamoun border areas, both the Islamic State and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham maintain an active presence. The two groups recently engaged in a round of fierce infighting, with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham in alignment with another group called Saraya Ahl al-Sham. In al-Qasr though, a key matter of concern in the area stems from problems between the Lebanese state and the Ja’afar family. These problems have arisen on account of the killing of a young man called Hadi Ja’afar at a checkpoint being run by members of the Lebanese army intelligence in September 2016. The exact reason for the killing is not clear, but the incident prompted Hadi’s father al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar, a prominent member of the Ja’afar clan and wealthy businessman from al-Qasr, to take revenge on the perpetrator by organizing his killing with his own personal hit squad in the Sayyida Zainab area of Damascus. Owing to the problems that have arisen with the Lebanese state through this cycle of killing and revenge, members of the Ja’afar family, armed with rifles, now conduct night patrols in case of any attack by enemies from the Lebanese army.

| Poster commemorating Hadi Ja’afar. Photo author’s own. |

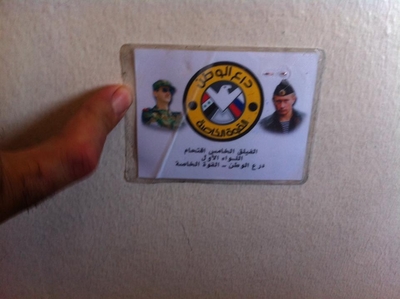

Prior to the Syrian civil war, al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar was involved in business projects in Beirut and the Sayyida Zainab area. He is now said to run an illegal crossing that facilitates movement of goods like food products and clothes between Syria and Lebanon (smuggling of course is nothing new in this region). Yet al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar is more than just a prominent clan figure and businessman in al-Qasr. He is also the leader of a new militia outfit operating in Syria under the name of Katibat Dir’ al-Watan (Homeland Shield Battalion). The group is specifically affiliated with the first brigade of the Fifth Legion (V Corps), a project set up in late 2016 and backed by Russia that aims to bring together elements of a variety of auxiliary formations to act as an assault force, offering a relatively high salary of $200 per month in a bid to attract new recruits on a mostly voluntary basis. Indeed, Katibat Dir’ al-Watan emphasizes the Russian support through including the Russian flag in its emblem. In an interview, al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar, who does not have Syrian nationality, confirmed to me that his group and the Fifth Legion more generally are only backed by Russia through provision of financial and armed support. He also claimed that Russian support comes through the ability to call for Russian air support where necessary.

| al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar’s Katibat Dir’ al-Watan ID card (his details are on the back of the card). Note the Russian flag in the group’s emblem, as well as the portrait of Vladimir Putin on the right of the card and Bashar al-Assad’s portrait on the left. The text reads: “Fifth Legion- Assault. First Brigade. Dir’ al-Watan: Special Force.” Photo author’s own. |

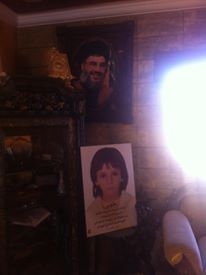

One of the bigger controversies surrounding the Syrian civil war is the relationship between Russia and Iran with regards to supporting the regime. Are the two powers in intense competition for influence, or are they a united front/axis? On one reading, for instance, the Fifth Legion project is a Russian initiative to try to push back against Iranian influence in the country by backing formations more associated with the Syrian state. Katibat Dir’ al-Watan presents an interesting case study for anyone trying to answer these difficult questions. While the group does not receive backing from Iran, al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar’s affinities with Hezbollah, Iran’s main client in Lebanon, could not have been more obvious, with a portrait of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in his house. Organizationally, al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar is not in Hezbollah, but he has worked with the organization to facilitate its affairs in the border areas, and spoke of being on the same ideological path as Hezbollah. He also invoked similar political talking points such as denouncing the U.S. as “the Great Satan,” while making clear that he only meant this term in terms of the U.S. as a political entity and not the entire American people, among whom he conceded that there are Americans who adhere to “humanitarian” values. Other links to Hezbollah are apparent in the fact that al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar’s brother and Katibat Dir’ al-Watan’s deputy leader, al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar, is a member of Hezbollah, as is al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar’s son Akram, who is also in Katibat Dir’ al-Watan’s ranks. Another son of al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar, Ali, is currently doing a military training course with Hezbollah. It is hard to imagine that the Russians are somehow unaware of these Hezbollah connections.

| Portrait of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah inside al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar’s house. Photo author’s own. |

For his own part, al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar downplayed the idea of competition between Russia and Iran, while also taking a more diplomatic line on the problems being faced by the regular Syrian army. Just as Russia has its own field of responsibility designated to it within the Syrian area, he explained, so this was also the case for Iran. While admitting problems of desertion from the ranks of the Syrian army, al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar explained away these issues as a natural outcome of the long civil war: “It is impossible for an army to fight for seven years and be responsible for everything.”

| In centre: al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar, who has a training camp in Tartous for Katibat Dir’ al-Watan recruits. |

To an extent, there is truth to these words, though al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar was much more forthcoming about the flaws of the Syrian army and military leadership. As he put it rather bluntly to me on one occasion, “The Syrians are not good.” While noting that there might be some in the Syrian army who could qualify as “heroes,” he explained that the reality is that the army is bedevilled by problems of corruption and often withdraws from its positions quickly, and that terms of military service difficult. “20 Hezbollah fighters are equivalent to 1000 Syrian soldiers,” he claimed. In fact, incompetence and corruption in the Syrian military leadership in contrast with al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar were supposedly part of the reason the Russians deemed him appropriate to lead Katibat Dir’ al-Watan. The two men also spoke differently of the regime more generally: that is, al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar tended to adopt talking familiar regime talking points, while al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar was more critical of the regime. Berating the Gulf states for not supporting true Arab and Muslim causes, al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar asked, “10,000,000 demonstrators came out in support of the government as opposed to 10,000 [for the opposition], with whom did the Gulf states go?” In contrast, al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar was willing to concede some popular basis for anger against the regime, describing its intelligence apparatuses in particular as “oppressive,” frequently detaining people without just cause.

| On left: al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar. On right: al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar. This photo was taken in the Palmyra area. |

So what is the long-term goal of the Katibat Dir’ al-Watan project? At present, the group is only allowed to operate legally inside Syrian territory, with its main deployment at present on the Palmyra front against the Islamic State. “God willing, the battalion will become a brigade,” explained al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar, adding that recruitment among Syrians, who constitute most of the group’s rank-and-file of an estimated 400-500 fighters as of May 2017, was also occurring in Hama and Aleppo. Undoubtedly therefore, like many other militia leaders in the Syrian arena, he is seeking to build his own client network and web of influence.

| Inside al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar’s home: sitting room featuring a portrait of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamene’i. |

Yet his ambitions (and those of the Katibat Dir’ al-Watan leadership) also look inward towards Lebanon. In particular, the “dream” (to use al-Hajj Muhammad al-Ja’afar’s words) is to set up a new political movement, a prospect that would only be viable if the Russians provide support for this project, according to al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar. Of course, another key factor would be whether Katibat Dir’ al-Watan could become a legal force to operate inside Lebanon. While the political planned movement would be ideologically aligned with the broader ‘resistance’ axis, the goal of it would be to represent better the interests of the local people, in particular the clans of these northern borderlands but perhaps extending to the wider Beqaa region. As al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar explained, the grievance of marginalisation is not confined to a particular sect in his view: “There is marginalisation of Sunnis, Shi’a and Christians.” He put this problem down to Lebanon’s sectarian muhassasa system and the mutual agreements parties strike to share positions, meaning that the same politicians remain in place without representing the will of local constituencies. He singled out Nabih Berri, the 79-year-old leader of the Amal Movement, as one of the worst cases exemplifying this state of affairs. Despite his affiliation with Hezbollah, he acknowledged that the organization was not free of criticism in this regard through striking power sharing agreements with the Amal Movement, besides the fact that “some of the new members are not restrained” by Hezbollah’s codes of conduct, something that he partly attributed to the war in Syria that has killed many older and more senior Hezbollah personnel.

Thus, the planned political movement could be summed up along the lines as ‘reformist-resistance’, ideologically of the same orientation but seeking to change how politics works in representing local interests inside of Lebanon. Perhaps like the Syrian Social Nationalist Party of Lebanon, Katibat Dir’ al-Watan could end up seeking political influence inside of Syria as well through seeking election of MPs to the Syrian parliament. Much will depend on how far Katibat Dir’ al-Watan expands its networks.

————–

Appendix: Key figures in Katibat Dir’ al-Watan.

– al-Hajj Muhammad Ja’afar: Overall leader

– al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar: Deputy leader

– Ghassan Ja’afar: Second deputy. From al-Qasr.

– Akram Ja’afar: Son of al-Hajj Hussein Ja’afar. A military commander for Katibat Dir’ al-Watan.

– Muhammad al-Jamal: Field commander for Katibat Dir’ al-Watan. He is from al-Qasr.

– Mahdi al-Jamal: Recruitment official, from Zeita.

– Hassan al-Jamal: Mahdi’s brother. Another recruitment official.

Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi is a graduate from Brasenose College, Oxford University, and a Jihad-Intel Research Fellow at the Middle East Forum. This article is reposted from this website. You can read the original here.

Image: Photo: A Lebanese soldier carries his weapon as he stands on sandbags at an army post in the hills above the Lebanese town of Arsal, near the border with Syria, Lebanon September 21, 2016. Picture taken September 21, 2016. REUTERS/Mohamed Azakir