Eight questions (and expert answers) on the SDF’s withdrawal from Syria’s Aleppo

Hundreds of displaced families are returning to—and Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters are withdrawing from—the city of Aleppo in northern Syria, after a US-mediated cease-fire there ended a week of violent clashes with government forces. Damascus has now taken control of the city, after a week that highlighted foundational challenges for the new Syria.

The outbreak of violence killed more than twenty people, according to media reports, and displaced thousands of Aleppo residents.

It’s the latest iteration of conflict in a consequential and difficult year for Syria, as the country seeks to build stability after the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime and over a decade of brutal and factionalized civil conflict.

Our experts unpack why violence erupted, what it means for Kurdish and wider minority safety and integration under the new Syrian government, and how Washington is engaging.

1. What is the political and military background of this conflict?

On April 1, Damascus and the Kurdish People’s Defense Units (YPG)-dominated SDF agreed on a localized integration arrangement covering the two SDF-held neighborhoods of Aleppo city. Despite the initial atmosphere of goodwill, SDF-affiliated Asayish forces that remained in these neighborhoods obstructed the implementation phase and refused to subordinate themselves to Aleppo’s Internal Security Forces, as stipulated in the agreement.

On multiple occasions, Asayish units attacked civilians and civilian infrastructure, triggering violent clashes. Throughout this period, Damascus repeatedly agreed to cease-fires in an effort to preserve negotiations over the broader March 10 integration agreement with the SDF. However, after the deadline of the integration deal expired, final US-mediated talks in Damascus failed, and Asayish forces again targeted civilian infrastructure, and the Syrian army opted to launch a limited military operation.

—Ömer Özkizilcik is a nonresident senior fellow for the Syria Project in the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs.

For the last fourteen years, the Kurds enjoyed de facto autonomy, and they currently control a large chunk of eastern and northeastern Syria. An agreement inked in March last year, which the Kurds reluctantly agreed to under immense external pressure, was meant to see the SDF and the Kurdish civilian institutions integrated into the Syrian state. It has effectively gone nowhere, with both sides blaming each other.

The fighting in Aleppo broke out just days after negotiations stalled again and came to an end after external forces, notably the United States, intervened, preventing a potentially greater bloodbath. Turkey stated it would take action—if needed—on behalf of the Syrian government, and Israel threw its weight in behind the Kurds.

—Arwa Damon is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East and president and founder of the International Network for Aid, Relief, and Assistance (INARA).

2. What does the withdrawal of SDF-affiliated units mean for stability in Aleppo?

The withdrawal does bring with it a sigh of relief for the residents of Aleppo. But taking stock of the destruction, for those who lost loved ones, it’s hardly a win. The days-long fighting further ripped open one of the many fissures that the Syrian government says it has been trying to repair as it attempts to consolidate power under Damascus. The Kurdish population—who largely remain wary of President Ahmed al-Sharaa’s government—might just prove to be the toughest to win over.

While an even worse scenario has been avoided for the time being, if anything, the fighting is evidence of how much more work lies ahead for Syria and how its path to “stability” will not necessarily be free of suffering.

—Arwa Damon

3. What does the dismantling of the Kurdish military presence in Aleppo mean for SDF status in Syria?

Losing Aleppo weakens the SDF’s negotiating position significantly. Damascus will never support the SDF in retaining an autonomous military or administrative structure in the northeast, but al-Sharaa has repeatedly said that Kurdish language and cultural rights will be enshrined in the future constitution. The current government is already highly localized, and we will likely see the same model applied to the northeast with or without a peaceful integration of the SDF.

—Gregory Waters is a nonresident senior fellow for the Syria Project in the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs and writes about Syria’s security institutions and social dynamics.

4. How credible are government assurances of inclusion and rights protections to Kurdish communities?

The components of the new Syrian government have a mixed track record of treatment towards Kurds. The factions that came from Idlib, most notably Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, have no serious history of ethnic targeting of Kurds, while several Syrian National Army (SNA) factions, which now serve in parts of the new army, have been sanctioned for years for systematic abuses against Kurds in northern Aleppo. It is now up to Damascus to ensure these ex-SNA factions no longer abuse or exploit Kurdish communities.

—Gregory Waters

There were no reports of large-scale violations by government security forces during the fighting in the Sheikh Maqsood and Ashrafiye neighborhoods, unlike the abuses that occurred in coastal areas or in Swaida last year. This demonstrates progress in managing security operations in areas where diverse communities live. Another episode of violence and killings would be too costly politically for Damascus. In Aleppo, security forces have been overall mindful to show that they are able to protect the Kurdish community.

—Marie Forestier is a nonresident senior fellow for the Syria Project in the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs. She is also currently a consultant for the European Institute of Peace.

Related reading

5. What does the Aleppo violence imply for future negotiations with other armed groups?

The issue in Aleppo is distinct from more general political or ideological dissent in Syria because it involved an armed group that controls territory. However, the government’s slower, methodical approach to the dispute this week, mixing continued diplomatic outreach with military pressure, shows a more mature leadership in Damascus compared to how it approached similar dissent in Swaida in July.

—Gregory Waters

Related reading

The operation in Aleppo was not a response to dissent, but rather a consequence of the deadlock of negotiations. A significant part of the Syrian population would like to see Kurds and the northeastern region fully integrated into the new Syria. The positive outcome of the military operation in Aleppo—at least from the government’s perspective—and the way security forces managed it raise the question of a possible replication of a similar operation in other areas in the northeast.

—Marie Forestier

6. How does the confrontation fit into the broader Turkish-Israeli rivalry over Syria?

Israel and Turkey hold fundamentally opposing views on Syria. Ankara sees the evolving situation as an opportunity to promote stability through a strong and centralized Syrian state, while Israel views such an outcome as a strategic threat and prefers a weak and fragmented Syria.

During the clashes in Aleppo city, both countries once again positioned themselves on opposite sides. The intensity and limited duration of the fighting did not allow for direct or indirect intervention by either actor. Nevertheless, Turkey publicly signaled its readiness to support the Syrian army if requested, while Israel called on the international community to protect the Kurds. This contrast underscores Turkey’s greater capacity to intervene in northern Syria, as well as the constraints on Israel’s options.

In light of the outcome in Aleppo city, Turkey’s vision of a unified Syria appears to have scored a tactical victory. At the same time, the episode served as a reminder that Turkish-Israeli competition over Syria—rooted in irreconcilable strategic perspectives—will persist.

—Ömer Özkizilcik

7. Where does the United States stand in all of this?

The escalation highlights two key realities for US policy in Syria. First, US mediation efforts aimed at facilitating integration and supporting a unified Syrian state have failed. Washington repeatedly brought Damascus and the SDF to the negotiating table and attempted to steer the process in a constructive direction, yet no breakthrough was achieved.

Second, the crisis has created a new opportunity for the United States. The exposure of the SDF’s fragility in Aleppo city may increase its willingness to make concessions and accept Damascus’s terms. If Washington seeks to prevent a broader military escalation in northeastern Syria, it can once again convene talks and press the SDF to adopt a more pragmatic stance. Should the SDF demonstrate genuine willingness, the United States could play a constructive role in facilitating integration and rebuilding trust between the parties.

—Ömer Özkizilcik

Related reading

8. Did disagreements among SDF factions contribute to the violence?

The exact degree of internal disagreement within the SDF—and the extent of central command control over Asayish forces in Aleppo—remains contested. Nonetheless, it is evident that multiple decision-making centers are involved. Following the escalation, Damascus and the SDF agreed, under international mediation, to evacuate all Asayish forces from the contested neighborhoods. Some Asayish units, however, refused to comply and instead chose to fight.

According to Turkish intelligence sources cited in the media, this decision followed orders issued by Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) cadres in Qandil, reportedly led by Bahoz Erdal. This suggests a rift between the Syrian branch of the PKK, which dominates the SDF, and the PKK’s central leadership in the Qandil Mountains of northern Iraq.

A second layer of fragmentation became visible on the battlefield itself. While the Syrian army initially pursued a limited operation, cohesion within the Asayish ranks collapsed, with many fighters deserting or laying down their weapons.

—Ömer Özkizilcik

Further reading

Sun, Dec 7, 2025

One year after Assad’s fall, here’s what’s needed to advance justice for Syrians

MENASource By

The second year of a post-Assad Syria requires structural reform, victim-centered leadership, and international reinforcement.

Wed, Sep 24, 2025

Is a new era of Turkey-Syria economic engagement on the horizon?

MENASource By

The convergence of Turkey's and the Gulf's economic strategies in Syria presents an opportunity for Washington.

Tue, Dec 16, 2025

What will 2026 bring for the Middle East and North Africa?

MENASource By

As 2025 comes to a close, our senior analysts unpack the most prominent trends and topics they are tracking for the new year.

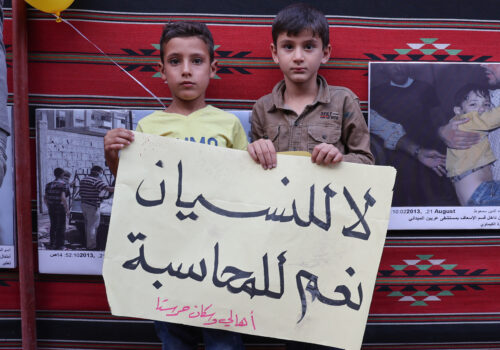

Image: Members of the general security forces patrol the Sheikh Maksoud neighbourhood after taking control of the area, following the collapse of an agreement between the Syrian government and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), in Aleppo, Syria, January 10, 2026. REUTERS/Khalil Ashawi TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY