Syria’s civil society must take center stage in reconstruction

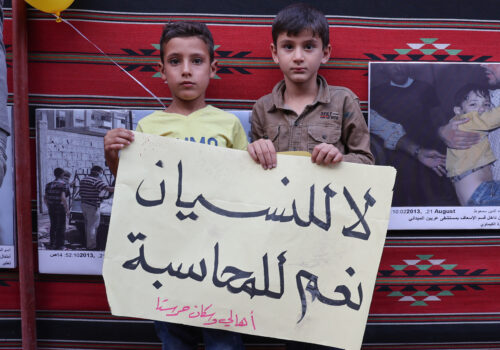

Khaled is a forty-year-old businessman from Eastern Ghouta in Syria. He says he lost fifteen family members—including his parents, siblings, pregnant wife, and two-year-old son—in the 2013 chemical attacks that Bashar al-Assad’s regime is accused of having been responsible for.

He recalls holding his wife as she recited the Tashahhud before the gas and the airstrikes that followed “erased all life,” and he later lost a second wife to another strike during the siege.

This September, sitting in his workshop that he rebuilt from the rubble, Khaled told one of the authors that he is working hard to restart the furniture business that once sustained his family. After years in Idlib and Turkey, he has returned to Eastern Ghouta—strictly driven by what he calls a “simple hope for peace and stability,” and a vow to “do whatever it takes to rebuild” his devastated town.

His suffering, he says, would be worth reliving “so long as it means I get to rebuild this country.”

One year since Assad’s fall and amid the steepest US development aid cuts in decades, Syria—a country that for over a decade was regarded as one of the worst humanitarian crises of the modern century—stands to have the most potential to showcase how local ownership, civil society, and a grassroots focus can accelerate reconstruction.

As is the case in many other parts of the region that have endured years of conflict, invasion, and destruction, Syria’s real infrastructure today is not physical, but human—the one thing that cannot be replaced, bypassed, or shortchanged by aid or the deficit of it. Syrian civil society must be a central architect to Syria’s rebuilding—not an afterthought to anyone’s investment. Today, the future of development rests not in big donor money or foreign aid but in a country’s most valuable asset: its people.

A 2017 State Department evaluation of Syrian civil society projects highlighted “local buy-in and ownership are key to project success in the short and long-term.” The evaluation recommended that there should be “consistent opportunities” for civil society organizations and grassroots communities to “provide input” to the project at hand from the get-go regarding community needs, training topics, and feedback throughout the project’s life cycle. For a country with a pre-war economy of roughly $60 billion, and whose physical reconstruction alone the World Bank now estimates at around $216 billion, Syria represents not just a humanitarian obligation, but a momentous opportunity to reimagine how investment, local ownership, and rebuilding can go hand in hand—setting an example for the rest of the Middle East and North Africa region, where tragically other conflicts linger in Gaza, Yemen, Libya, and Sudan.

One year on from the start of life in a post-Assad Syria, the country faces a historic moment to set a regional example anchored in the most durable, valuable, and scalable asset of any nation, which remains its civil society.

Related reading

Rebuilding in Syria

In just the first few months since Syria’s emergence on the international stage, the country signed more than $14 billion worth of major investment agreements with regional and international companies—including investments from European donors, Gulf states (such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar), multilateral banks, and private companies that have moved into the country’s reconstruction sector. This includes the $5.8 billion in grants and loans pledged at the 2025 Brussels conference to the expansion of economic engagement with Turkey, the hundreds of millions of dollars in new Gulf-backed port and industrial-zone deals that are still a fraction of the roughly $216 billion the World Bank estimates full rebuilding will require.

Saudi Arabia, whose de facto ruler Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman is a key backer of Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa’s government, signed forty-seven investment agreements and memorandums of understanding at the July 2025 Saudi-Syrian Investment Forum. Most of these investments are focused on rebuilding Syria’s infrastructure across various sectors, including transportation and construction—especially residential—as well as energy, maritime, and industry.

However, what’s indispensable to any form of sufficient, scalable, and sustainable development is that these public and private actors treat local Syrian councils, civic organizations, educators, and technicians as co-designers, facilitators, and contract partners.

Civil society as Syria’s greatest asset

These sectors provide a unique opportunity for engaging local actors in Syria. This includes the civil society organizations and community leaders that played a prominent role in maintaining basic services and key development projects amidst the horrors of the country’s civil war.

The White Helmets represent a key example. The humanitarian grassroots organization was formed in Aleppo and the surrounding countryside, saving civilian lives under perpetual airstrikes and shelling by the Assad regime and clearing the rubble and debris afterward, all at a time when no international aid could reach them. Their role grew into successfully repairing roads, reconnecting water networks in rebel-held districts, and providing key services to Syrians, including health and training to local community members.

It therefore came as no surprise that their founder, Raed Saleh, was appointed to Syria’s new cabinet as minister of emergencies and disaster management when the new government came to power. Today, he is bringing his decade-plus experience and community networks to the entire country.

In the northern Idlib province, previously ruled by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—the Islamist militant group that ultimately broke with Assad’s rule—various civil society organizations such as Kesh Malek, the Mazaya Women’s Organization, and the Violet Organization for Relief and Development provided educational and literacy support, women’s empowerment initiatives, teacher trainings, vocational training, and civic-leadership programs designed to prepare the next generation of Syrians to rebuild their country.

In Duma, a suburb of Damascus that endured years of siege (including the deadly April 2018 chemical attacks claimed to be executed by the Assad regime), people such as Ameen Badran, an activist and local community council member, started arranging garbage pickups and today continue to engage in reconstruction efforts even after al-Sharaa’s government appointed a mayor.

Similarly, in Zabaadni, after the fall of Assad, English teacher Alaa Zain Al Den told one of the authors that “the trauma on us was so much that we don’t even know what to do with this newly found freedom and joy.”

“However,” he added, “what we do know is that we want to rebuild, we want to start our work—the work that was taken from us.”

Today, Syria’s education system lies in ruins, with over half of the five million school-age children currently out of school and around seven to eight thousand schools damaged or destroyed across the country. This educational breakdown underlines why rebuilding must rely on local knowledge and community-rooted institutions that only Syrians, with firsthand awareness of what their neighborhoods truly need, can design. This is one sector that incoming investments should focus on as it helps to develop a new generation of Syrians for a revived economy.

Alaa and many hundreds of educators alike remained in Syria through the war. Expelled from his government teaching post in 2017 after refusing conscription into Assad’s army, Alaa spent years in limbo, unable to find stable work as the economy collapsed. The cost of that decision was immense. For years, he lived in hiding, while his brother was arrested during the war. Alaa’s family found out recently that his brother was killed in prison. Despite the scars, he and other teachers now hope for a chance to return to their classrooms and rebuild a broken educational system.

“Reconstruction in Syria will be meaningless if it is not built on the lived experience of Syrians themselves. Our communities know exactly what was destroyed—and what it takes to rebuild in a way that lasts,” said Anas, another educator who works in the same school as Alaa in Zabadani.

Private sector-led workforce development

These are just a few examples of some of the individuals, grassroots organizations, and local initiatives that have the experience, local knowledge, and networks to work with the private sector—both Syrian and international—to effectively contribute to this essential rebuilding process.

Where there is a skills gap, especially in technology-heavy sectors, companies investing in Syria must commit to training and up-skilling Syrians, not just as future employees, but as future managers, executives, and leaders. This requires a workforce-development formula that moves beyond traditional international-aid models and instead places private enterprises at the center of project design, implementation, and assessment, allowing their sector-specific needs to shape training pipelines and employment pathways.

A successful example of this approach is Jordan’s Luminus Technical University College (LTUC)—a private-sector–funded institution that reimagined vocational and technical education by linking all its programs directly to labor-market demand and employer input. Today, LTUC offers fifty accredited programs across twelve specializations, including information technology, engineering, creative media, construction, and health and safety—all fields that mirror the urgent reconstruction needs identified for Syria in assessments by the World Bank and United Nations Development Programme that emphasize shortages in skilled engineers, technicians, digital-economy workers, and construction professionals.

Local ownership of reconstruction initiatives brings with it core elements that may sound frivolous for international heavy hitters but are proven to be key ingredients of long-lasting success. Chief among these foundational pillars are local integrity and purpose, in addition to deep knowledge of a complex and multidimensional sociocultural context.

Hisham Tinawi—a once successful shopkeeper in Zabadani whose home was destroyed under heavy artillery and airstrikes—explains how “local communities possess the precise knowledge of the destruction and how to build viable solutions.”

He added that “those who remained inside the country possess accumulated field experience that no external party can replace; excluding them from the reconstruction process means excluding the truth from the picture.” Syrians see themselves not as bystanders to a new future that they paid for with their blood and tears, but as core partners in rebuilding.

“Effective reconstruction cannot be conceived without linking it to the voice of Syrians on the ground; we are not just beneficiaries but key partners with a clear vision of the future we want,” Tinawi told the author.

Today, investors—regional and global—must heed Tinawi’s advice and invest in education and workforce development training, as a start. Syria’s civil society remains its biggest asset and has proven ready and effective at rebuilding a Syria they so deeply deserve.

Tara Kangarlou is an award-winning global affairs journalist, author, and humanitarian who has worked with news outlets such as NBC, CNN, CNN International, and Al Jazeera America. She is also the author of the bestselling book The Heartbeat of Iran, the founder of nonprofit Art of Hope, and an adjunct professor at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service, teaching on humanized storytelling and journalism.

Merissa Khurma is the founder and chief executive officer of AMENA Strategies, an associate fellow at the Middle East Institute, and a nonresident fellow at the Baker Institute. She formerly headed the Middle East program at the Wilson Center.

Further reading

Thu, Sep 4, 2025

Dispatches from Damascus: The state of Syria’s postwar transition nine months after Assad’s fall

New Atlanticist By

On a recent trip to the Syrian capital, Atlantic Council experts took note of how far the country has come since the Assad regime’s fall and what still needs to happen to secure peace and prosperity.

Fri, Nov 21, 2025

Syria joining the anti-ISIS coalition is a westward pivot—with opportunities and risks

MENASource By

The decision is a shift in the country’s alignment—from Russian and Iranian spheres of influence to one in NATO and GCC regional orbits.

Wed, Sep 17, 2025

In landmark Syria elections, women still face electoral hurdles

MENASource By Marie Forestier

As the indirect electoral process begins, Syrian officials could take several steps to increase women’s chances in this process.

Image: Syrian men take part in reconstruction work in the City Aleppo, ahead of the first anniversary of Aleppo City liberation following the "Deterrence of Aggression" battle launched by the Syrian opposition on November 27, 2024, which toppled Bashar al-Assad's regime on December 8, 2024.