A year into its post-Assad era, Syria needs a ‘rules-first’ reset

Bottom lines up front

- Ahmed al-Sharaa has kept Syria’s postwar state standing for a year—but endurance alone cannot define success.

- Prosperity will depend as much on legitimacy and rules-based governance as on physical reconstruction.

- Look to the integrity of local governance, freedom of speech, and open access to information as the measure of whether democracy is taking root in Syria—not national elections.

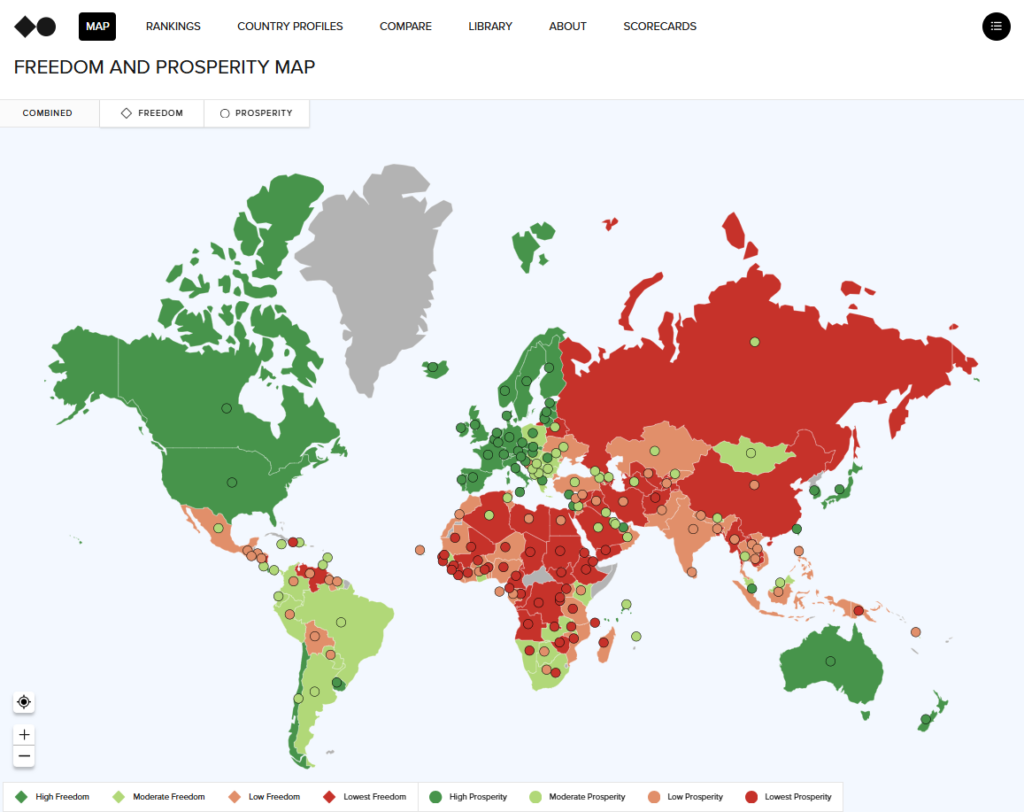

This is the fifth chapter in the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s 2026 Atlas, which analyzes the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

Evolution of freedom

The trajectory of Syria’s freedom over the past quarter century can be understood as a story of three phases: an early period of managed optimism and limited reform that ended in disappointment and repression; a second phase of tightening control and economic capture that eroded confidence even before the 2011 uprising; and a third phase of comprehensive collapse in political, legal, and economic freedoms during the long war that followed. The Freedom Index data traces these transitions clearly: a mild rise in the early 2000s, an economic dip before 2011, and an abrupt institutional implosion thereafter. Yet, behind the data lies a deeper pattern that continues to shape Syria’s current transition—an enduring struggle between the promise of modernization and the persistence of a centralized, personalized, and coercive power.

2000–07: Managed optimism and early contradictions

The first years of Bashar al-Assad’s rule unfolded against nearly four decades of Ba’athist and Assad-led authoritarianism. The Ba’ath Party’s 1963 coup had militarized politics and subordinated civilian institutions to a one-party state; his father Hafez al-Assad’s 1970 intraparty coup then consolidated this system into personalist rule, fusing state, party, and ruler. Within this entrenched structure, the younger Assad’s accession in 2000 generated cautious hope—not because the system had changed, but because many believed a younger leader might soften and modernize it. Some Freedom Index components—particularly economic openness and property-rights protection—showed mild improvement, reflecting initial confidence in the language of reform and the introduction of a “social-market economy.” Yet the momentum soon faltered. By the mid-2000s, Index data already registered dips in investment freedom and property rights, a signal that reform rhetoric was colliding with entrenched patronage.

Economic and legal subindexes were already falling by the mid-2000s, long before the uprising.

Behind those numbers lay an experiment in modernization without inclusion. The regime’s selective liberalization opened markets but not competition. Licensing remained opaque; access depended on political connections; and the same families who had prospered under the command economy swiftly adapted to dominate the market economy. Political openings were equally brief: The Damascus Spring of 2000–01, with its independent salons and petitions, ended in arrests and renewed surveillance. The early 2000s thus offered Syrians a glimpse of change without the institutions to sustain it. The indices captured this ambivalence—a brief uptick followed by regression—mirroring a public mood of anticipation that gave way to mistrust.

2007–11: Capture, control, and the erosion of trust

Investment Law No. 8 of 2007 briefly attracted foreign capital, but regime-adjacent conglomerates and the president’s relatives soon moved to dominate the very sectors opened by the law. In the ensuing years, Syria’s reform narrative hardened into a coerced-partnership economy. Foreign and domestic investors faced pressure to surrender shares to insiders; profitability again depended on proximity to power. The Freedom Index captures this shift: Between 2007 and 2010, the economic subindex declined, led by property rights and investment freedom, while legal subindex and political subindex stagnated.

Simultaneously, new urban-redevelopment laws expanded the state’s authority to rezone and clear “unregulated districts,” or informal settlements. The combination of vague statutes and deep-seated corruption convinced many Syrians that these projects were vehicles for dispossession. Anxiety was especially acute in lower-middle-class informal neighborhoods, where decades of tolerance for these settlements collided with new administrative discretion. Because many of these districts were Sunni-majority, fears of expropriation intersected with a sense of demographic vulnerability. Whether or not demographic engineering was the intended outcome, the very perception that it was exposed sectarian tensions that had been long suppressed but never resolved.

The growing dominance of Assad’s relatives and a narrow crony elite in business mirrored the earlier capture of the military and security apparatus. When protests began in 2011, early slogans denounced corruption and “the cousins,” in reference to the president’s extended family members and cronies, before calling for Assad’s removal. What appeared in the data as stagnation was experienced socially as exclusion. Even though the Prosperity Index’s inequality component remained flat during these years—a statistical artifact of missing data—the lived reality was one of widening disparities. Liberalization without competition concentrated wealth among insiders, while provincial regions and informal labor markets stagnated. For many Syrians, upward mobility increasingly depended on connections, not effort; corruption shifted from a tolerated survival mechanism to a symptom of structural injustice. Thus, the erosion of trust that would fuel the 2011 uprising was already well underway, even if the dataset does not fully capture it.

2011–present: Collapse and authoritarian adaptation

The 2011 uprising pushed Syria’s long deterioration into a systemic collapse. The regime’s decision to pursue a military solution removed any prospect of negotiated reform, triggering an immediate plunge in civil liberties, political participation, and legislative oversight from what was already a low baseline. As violence escalated, the rule of law quickly fell apart: Judicial independence fully dissolved, bureaucratic discretion replaced predictability, and state institutions morphed into rent-extraction networks. The economic subindex also crumbled as productive capacity disintegrated, trade routes fractured, and the war economy—with its intermediaries controlling checkpoints, fuel distribution, smuggling routes, and later the narcotics trade—became the dominant source of revenue.

Sanctions dating back to 1979, expanded in 2004, and tightened after 2011, culminating in the Caesar Act in 2019, deepened isolation and contributed to sharp declines in trade freedom. The regime’s workarounds—barter arrangements and selective contracting with Russia and Iran—kept some sectors afloat but entrenched discretionary governance rather than promoting reform. By the late 2010s, many political, legal, and economic subindexes had dropped to their statistical floor, offering a deceptive appearance of stability that masked continued decay. For citizens, the state functioned less and less as an arbiter of law and more as a gatekeeper of favors until political repression, institutional breakdown, and economic predation converged into a single authoritarian survival strategy.

Freedom did not collapse because of war; war revealed the cumulative effects of its earlier absence.

An exception appears in women’s economic freedom. Modest improvements in 2010 and 2019 stem from statutory reforms—Labor Law 17 banning gender discrimination and amendments to the Personal Status Law expanding women’s mobility—but these changes coincided with collapsing enforcement. War thrust millions of women into economic roles without legal protection, widening the gap between the law and their lived reality. The indices record formal progress while women, in practice, felt its absence.

Across all three phases since 2000, Syria provides evidence that the erosion of freedom precedes crises. Economic and legal subindexes were already falling by the mid-2000s, long before the uprising. Freedom did not collapse because of war; war revealed the cumulative effects of its earlier absence. The same forces that hollowed freedom—capture, mistrust, and legal decay—also undermined prosperity. Economic contraction, institutional breakdown, and the flight of human capital followed the same trajectory. The next section examines how the collapse of freedom translated into material impoverishment, and why rebuilding prosperity will depend as much on legitimacy and rule-based governance as on physical reconstruction.

Evolution of prosperity

The decline of prosperity in Syria mirrors the earlier erosion of freedom, and it follows the same three-phase rhythm: brief optimism, structural stagnation, and collapse. Prosperity, not only as material welfare but also as the capacity to convert freedom into opportunity, proved as fragile as the institutions meant to sustain it. The data shows that even before 2011, prosperity indicators were already plateauing, with income gains narrowing, education and health progress stalling, and income inequality rising. War then amplified those hidden weaknesses into outright devastation. Syria’s Prosperity Index dropped precipitously after 2011, reflecting the combined effects of conflict, sanctions, displacement, and the collapse of productive capacity. Yet the flattening of many post-2016 indicator time series—driven largely by missing data—should not be mistaken for stability. As with the freedom indicators, the real picture is worse than the charts can show.

Without credible investigations, equal enforcement of law, and inclusive local administration, rebuilding the infrastructure will not mend the social fabric.

The income component indicates a steep fall from 2011 onward, coinciding with the collapse of the Syrian currency, the destruction of infrastructure, and the disintegration of trade routes. The Freedom and Prosperity dataset registers a sharp contraction in real output; still, these numbers likely underestimate the true scale of decline. There is no reliable, published GDP data for Syria after 2010, or when informal economies—smuggling, remittances, and war profiteering—became dominant following the onset of civil war in 2011. What little production continued was concentrated in government-held areas and in a few rent-generating sectors such as fuel procurement and distribution—run by regime-connected intermediaries—and the burgeoning narcotics trade.

Health indicators reveal the same paradox present in the freedom data: an apparent mid-2010s increase that likely reflects statistical noise, not genuine improvement. Hospitals operate at a fraction of pre-war capacity; medicine supply chains remain disrupted by sanctions and infrastructure damage; and millions of Syrians rely on under-qualified private clinics or humanitarian relief. In the northeast, unregulated oil extraction and generator fumes have sharply increased respiratory illness, while fuel shortages elsewhere limit heating and sterilization.

Education was once one of Syria’s equalizers; it is now one of its deepest dividers. The early-2000s reforms that legalized private universities generated modest competition and raised standards from a low baseline—progress that is reflected in an uptick in the Education Index before 2011. The war erased those gains. School bombings, teacher flight, and long-term displacement closed thousands of educational institutions. Entire cohorts of students have missed years of schooling, particularly in the north and east. Literacy and attainment gaps are now intergenerational, with ripple effects on productivity and social mobility.

The Prosperity Index’s “treatment of minorities” component measures equal access to services and opportunities rather than formal rights. Syria’s scores here declined gradually after 2011, reflecting uneven governance across fragmented territories. Before the war, religious minorities were not systematically disadvantaged, while Arab-nationalist policy subjected ethnic Kurds to long-standing discrimination. The conflict changed or inverted many of these hierarchies. In the northeast, Kurdish self-administration improved service access for some communities but created new barriers for Arabs and ethnic minorities in the region; elsewhere, minority enclaves under government protection retained some services while majority-Sunni rural areas collapsed. The result is a map of geographic inequality that cuts across identity lines. The welfare of communities has come to depend less on who they are than where they live and which authority governs them. This fragmentation complicates measurement: The Prosperity Index’s national average flattens differences because it treats Syria as one unit, when in reality it is fractured into multiple zones of control.

Syria’s challenge is dual: restoring the state’s capacity while reconstructing a shared sense of belonging.

The Prosperity Index’s inequality components remains low and almost flat throughout the series—a statistical artifact of missing data, not evidence of equity. As noted in the Freedom Index section, this calm surface conceals the turbulence below. Before 2011, economic opening without competition had already concentrated wealth among regime insiders. After 2011, the war economy multiplied disparities: Commanders, brokers, and smugglers accumulated fortunes while public-sector wages cratered. Access to basic goods increasingly depended on connections—fuel, medicine, and even humanitarian aid were under the control of loyalty networks.

The path forward

Syria’s next chapter begins under conditions fundamentally different from those that shaped the early 2000s. When Assad assumed power, he inherited an intact authoritarian system and experimented briefly with controlled openings that were soon reversed. Since the regime’s collapse, I have returned to Syria repeatedly, most recently arriving right before the first anniversary of its fall, now commemorated by Syrians as Liberation Day. In streets filled with flags, music, and portraits of the revolution’s martyrs, the relief of emancipation coexists with a quiet unease about what comes next. It is within the tension between celebration and apprehension that the questions in this section take root.

In streets filled with flags, music, and portraits of the revolution’s martyrs, the relief of emancipation coexists with a quiet unease about what comes next.

Today’s transitional moment is not an echo of Assad’s accession: The state has been fractured, society transformed, and the political landscape irreversibly altered. Yet the experience of that earlier period offers a cautionary insight: Periods of optimism can generate movement but also instability and, without institutional safeguards, early progress may falter. The question now is not whether the current transition will replicate past cycles—it will not—but whether it can avoid the structural traps that undermined reform efforts and contributed to systemic collapse. This distinction is essential because Syria’s post-war trajectory will not follow a linear path. Transitions in deeply damaged states rarely do. They move forward unevenly, shift abruptly, and sometimes regress before stabilizing. Early improvements—whether in governance, service delivery, or the investment climate—may be evidence of hope more than durable change, just as setbacks may represent adjustment rather than failure. Assessing Syria’s progress, therefore, requires patience and multidimensional judgment: an approach that interprets fluctuation not as contradiction but as the normal rhythm of transition.

To navigate this complexity, I propose a three-pronged framework: stabilization, economic consolidation, and democratization. These are not sequential steps but overlapping phases of state-building that unfold simultaneously, even if each advances at a different speed. What matters is not only the tempo of reform but its substance: whether rules, institutions, and trust can come to replace coercion, discretion, and fear. The measure of Syria’s transition rests on whether predictability takes hold in administration, whether rights and responsibilities become rule-based, and whether meaningful participation—formal or informal—emerges as a stabilizing force. The remainder of this section examines what such a transition requires, the risks that could derail it, and the practical choices facing the government of Ahmed al-Sharaa as it attempts to move the country from mere survival toward accountable governance and inclusive prosperity.

The al-Sharaa government’s greatest early achievement has been institutional endurance. Ministries reopened, salaries resumed, and central agencies continued to function despite fiscal exhaustion and territorial fragmentation. Partial electricity improvements revived basic services, while the exemption of industrial machinery from customs duties and the reactivation of more than 1,500 factories signaled the first wave of Syria’s industrial recovery. Aleppo and rural Damascus led this rebound, benefiting from eased licensing procedures and the lifting of long-standing state monopolies. Together, these steps stabilized daily life and signaled that the state still existed.

Stability, however, does not constitute transformation. The real challenge is to turn functionality into legitimacy. With roughly half the population displaced and infrastructure drastically degraded, national elections cannot anchor stability. What can anchor stability is a rules-first reset—predictable administration, impartial security provision, and credible remedies for everyday predation. Electricity, water, and education are not merely utilities; they are the daily symbols citizens use to determine if a state has truly returned. When the lights come on predictably, people infer that authority functions. Service delivery reforms—metered electricity, local water management, transparent teacher recruitment—can demonstrate fairness more convincingly than political declarations. Over time, reliability in these domains begins to rebuild the social contract, shifting public perception of the state from coercion to provision.

The al-Sharaa administration has tried to make this link explicit by prioritizing the rehabilitation of power grids and the partial restoration of domestic production in reopened factories. These steps, modest but visible, have reintroduced a sense of continuity in daily life. Yet progress remains uneven, constrained by power shortages, financing gaps, and opaque contracting. Until public trust in hospitals, schools, and oversight mechanisms is restored, Syria’s institutions will remain nominally functional but substantively fragile. Without a minimal legal core—clear rules, enforcement, and functioning courts—investment will not return and social tensions will fester, regardless of political rhetoric. This sequencing aligns with what Syrians themselves emphasize: security, rule of law, and the restoration of basic services. The judiciary, local police, and municipal offices must become predictable entities rather than instruments of discretion. Every contract enforced and every property dispute resolved fairly will do more for legitimacy than a hundred speeches.

The early months of the al-Sharaa government have already revealed how fragile stabilization can be when inclusion and accountability lag behind coercion. In early 2025, violence in the coastal region—primarily targeting Alawites—exposed the inability of new security structures to protect citizens regardless of identity or locale, with investigators documenting murders, abductions, and property destruction in what they described as “widespread and systematic” attacks. In Sweida, clashes between Druze armed groups, Bedouin tribes, and government forces left hundreds dead and tens of thousands displaced. For minorities, these events underscored a central concern: not simply whether services return, but whether the state protects all communities equally and whether security is exercised as reassurance rather than predation.

Without credible investigations, equal enforcement of law, and inclusive local administration, rebuilding the infrastructure will not mend the social fabric. Syria’s challenge, therefore, is dual: restoring the state’s capacity while reconstructing a shared sense of belonging. Hyper-centralization, once justified by security concerns, eroded both legitimacy and responsiveness. Durable recovery requires decentralization within national frameworks—empowering municipalities, strengthening fiscal transparency, and guaranteeing that central oversight is procedural rather than political. In practice, this means allowing local administrative units to manage water, sanitation, and education budgets, while central ministries set national standards. The balance between authority and autonomy will determine whether new institutions can sustain both order and inclusion. The government’s newly created directorates for anti-smuggling and anti-corruption are a direct response to the previous regime’s entrenched culture of corruption. Enforcement has improved in curbing border smuggling but remains uneven in administrative corruption and procurement oversight. Under Assad, corruption evolved from grand theft by elites to everyday extortion within public offices; that legacy persists. Rooting out corrupt practices requires professional administration, digital tracking, and transparent contracting. The more promising path is systemic reform rather than episodic purges.

The abuses on the coast and the violence in Sweida illustrate how incomplete control and fragmented authority undermine claims to national coherence. Nowhere is this tension clearer than in the northeast. What began as a negotiation with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) has become a coercive effort to absorb territory, resources, and fighters into a centralized framework. Recent fighting, the loss of large swathes of SDF-controlled territory, and demands for individual—rather than unit—integration into the national army have transformed the issue from accommodation to consolidation. The outcome will hinge not only on restoring territorial control but also on whether Damascus can convert reunification into legitimacy—addressing fears of exclusion, ensuring equal protection across communities, and defining whether authority is exercised as domination or the foundation of a new social contract.

Stabilization will also falter if the security apparatus remains fragmented. The transformation from militia networks to accountable institutions is central to both freedom and prosperity. Priorities include unified command structures, professional training, and civilian oversight. Integrating vetted former combatants into national forces, while demobilizing others through economic reintegration programs, can reduce predation and restore public trust. Rule-bound policing—applied equally in the capital and on the periphery—will mark the difference between security as repression and security as reassurance.

Rebuilding Syria requires basic statistical capacity—not as a technocratic exercise but as a safeguard against arbitrariness. Reviving the Central Bureau of Statistics and digitizing government records would replace speculation with verifiable information and allow citizens, investors, and local officials to track progress. Reliable data—on prices, services, and reconstruction—will be essential to designing policy and restoring trust. Transparency in numbers, and public access to them, is fundamental to the institutional reconstruction Syria never experienced.

Economic recovery in Syria will depend primarily on credibility. Investors still remember the coerced partnerships, opaque privatization, and arbitrary taxation of the late 2000s. This is why dozens of memorandums of understanding since 2024 have yielded little tangible action. Capital will not return without enforceable property rights, transparent licensing, and reliable adjudication. In Syria, the strongest commitment device is an independent court, not a contract-signing ceremony. The new anti-corruption effort acknowledges how distorted the system had become, but enforcement remains uneven. Property restitution relies on clear rules and independent claims boards; procurement requires public tenders and published outcomes; and credit access must shift from patronage to rule-based lending. Democratizing these economic processes means opening them to professional associations, municipal councils, and public audits so that opportunity depends on rules, not connections.

Regional partners have shifted from aid to investment logic, making policy predictability Syria’s real currency. The 2025 renewable-energy law is a promising step, but implementation is hampered by financing gaps and missing technical standards. Household solar adoption shows ingenuity but also risk—from fires and battery hazards to toxic waste. A credible green transition requires regulation and institutional capacity. Environmental “improvements” in the data often reflect reduced industrial activity, not genuine resilience.

Reentry into regional political and economic frameworks can anchor reform if it is tied to measurable progress in governance and transparency. External partners can help raise the cost of backsliding by linking investment and aid to institutional benchmarks. The Syrian diaspora, meanwhile, represents an immense reservoir of skills and capital. The goal should be reconnection, not mere repatriation. Flexible arrangements such as remote participation, temporary return programs, joint research, and business ventures can channel expertise without overburdening domestic absorption capacity. Educational recovery inside Syria must complement these efforts to prevent a permanent skills divide between returnees and residents. Academic openness will be essential here: Universities must once again become spaces of inquiry, not ideology.

Foreign assistance should build capacity, not substitute for it. Donor programs that channel funds directly into ministries without transparency risk entrenching old habits. Effective aid requires performance benchmarks, local participation, and open reporting. International actors must coordinate to prevent parallel governance structures and align aid flows with national reform sequencing.

With half the Syrian population displaced and institutions fragile, the only viable path toward pluralism is a gradual one. The first tests of democratic involvement will appear not in national elections but in the integrity of local governance, freedom of speech, and the openness of information. In the absence of attainable national elections, freedom of speech is more than a moral principle; it is a practical test of how power is exercised: Dissent must be permitted, reporters must be able to work freely, and academics must be allowed to collaborate without political constraint. These conditions are measurable, captured in the Freedom Index through media independence and civic participation, and they create the necessary environment for accountability to take hold. As power configurations shift, durable stabilization demands visible protections for minorities and sanctions for discriminatory behavior by officials or armed actors. Equality of access—to services, employment, and opportunity—will matter more than symbolic inclusion. Local participation mechanisms below the national-election level can channel grievances constructively while broader political frameworks mature.

Every contract enforced and every property dispute resolved fairly will do more for legitimacy than a hundred speeches.

Roughly six million Syrian refugees and an equal number of internally displaced persons (IDP) cannot simply “return home.” Rapid, concentrated return to a few livable cities would overwhelm services and risk new unrest. A phased, voluntary, and service-first approach is essential: Prioritize resettlement of internally displaced populations, restore local infrastructure, and guarantee security before large-scale returns. The Syrian government has begun preliminary mapping of viable districts for IDP return, but it lacks the financing and legal clarity for property restitution. International partnerships should condition support on safety, compensation mechanisms, and livelihood readiness to prevent a second displacement wave. Managing this process transparently will also generate data critical to humanitarian planning. Addressing war-era abuses is politically sensitive but indispensable. Pragmatic sequencing begins with documentation and administrative reform, not mass prosecutions. Vetting security personnel, publishing detention records, and clarifying property ownership can signal the emergence of a new legal order. International support should focus on building evidentiary systems and judicial capacity so that accountability mechanisms strengthen rather than destabilize governance. Every credible dataset—on detainees, missing persons, or property claims—will serve both justice and institutional learning.

The al-Sharaa administration has kept the state standing—a significant achievement after years of disintegration—but endurance alone cannot define success. The next test is whether stabilization evolves into accountable governance and inclusive prosperity. Progress will not be linear. Early statistical improvements may reflect optimism more than lasting reform; later regressions may signify adjustment rather than failure. Recognizing this rhythm will be necessary for a realistic assessment. Each credible budget, each open dataset, and each fair court ruling can become a milestone. International observers will watch less for declarations than for data: how many schools reopen, how many licenses are issued transparently, and how many cases are adjudicated without interference.

These numbers—absent for over a decade—will be Syria’s new vocabulary of reform. Freedom and prosperity will advance together only when opportunity is governed by rules rather than favors. The Atlas of Freedom and Prosperity will register this evolution as data returns to the public domain. A functioning state is measurable; a free one is verifiable. In that sense, information is both the mirror and the maker of liberty. The underlying lesson of the past two decades remains constant: Prosperity cannot emerge from arbitrary power. Syria’s new trajectory depends on embedding predictability into law, equality into administration, and restraint into politics. Whether under transitional arrangements or long-term governance, durable freedom will stem less from proclamations than from institutions that work—and that are seen to work.

about the author

Ibrahim Al-Assil is a senior research fellow at Harvard University’s Middle East Initiative at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, where he serves as project lead of the Syria Transition Lab. He is also a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. His work examines geopolitics and political transitions in the Middle East.

Explore the data

The Indexes rank 164 countries around the world. Use our site to explore thirty years of data, compare countries and regions, and examine the subindexes and indicators that comprise our Indexes.

Stay Updated

Get the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s latest reports, research, and events.

Stay connected

Read all editions

2026 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Against a global backdrop of uncertainty, fragmentation, and shifting priorities, we invited leading economists and scholars to dive deep into the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries around the world. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

2025 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists, scholars, and diplomats analyze the state of freedom and prosperity in eighteen countries around the world, looking back not only on a consequential year but across twenty-nine years of data on markets, rights, and the rule of law.

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Image: Syrians celebrate the fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime. Photo via Shutterstock.

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media