How likely is a war between the United States and Russia?

How likely is a war between the United States and Russia?

According to Matthew Rojansky, director of the Wilson Center’s Kennan Institute, in a recent World Politics Review article, “a war between Russia and the United States is more likely today than at any time since the worst years of the Cold War.”

That’s strong language. If Rojansky is right, we should all be starting to worry.

Except that Rojansky isn’t right. More exactly, the point he makes rests on conceptual slipperiness—which means that his argument is incoherent. That matters. Sloppy language breeds sloppy thinking, and sloppy thinking makes for lousy policymaking.

Read Rojansky’s article carefully and you’ll notice that none of it, absolutely none of it, deals with war—if by war you mean a large-scale military conflict involving thousands of casualties. Indeed, after the above lead sentence about the likelihood of war, Rojansky continues as follows:

This may sound implausible or exaggerated to policymakers, journalists, and the wider public. Yet the fact remains that increasing deployments by both sides, coupled with severely constrained direct dialogue, mean that dangerous incidents will become far more likely and will be far harder to defuse and deescalate.

As that quotation makes clear, Rojansky is concerned with “dangerous incidents” such as “recent ‘near-miss’ incidents at sea and in the air, most notoriously in April, when a Russian fighter buzzed the USS Donald Cook in the Baltic Sea, passing just thirty feet above the ship’s deck.”

Rojansky is probably right to conclude that “it is only a matter of time before more such dangerous incidents between Russian and US or NATO forces occur.” And he may also be right to say, “The question then will be how well-equipped both sides are to manage the consequences. Judging by the state of the relationship overall, the answer is not very well at all.”

Policymakers in both Washington and Moscow should heed Rojansky’s call for better mechanisms for dealing with dangerous incidents. But should they really be worried about war?

The answer, alas, is yes, but for none of the reasons that Rojansky gives.

For starters, it should be obvious that the difference between a dangerous incident and a war is enormous. They are profoundly different things, and to suggest, as Rojansky does, that incidents will automatically escalate into wars is at best disingenuous. At worst, it’s egregiously careless thinking that, if heeded, would result in bizarre policies that may put too much attention on incidents and too little on the real reasons for wars.

Incidents don’t lead to wars, unless both sides are already bracing for a fight or one side is looking for a pretext to start a fight. Therefore, only one question really matters: are both sides bracing for a real fight, or is one side looking for a pretext to start a real fight?

Is the West in general and the United States in particular bracing for war with Russia? Even if you accept the paranoid Russian view of the world and believe that NATO is a monstrously aggressive, anti-Russian alliance, you’d be hard-pressed to argue that official Brussels or Washington or Berlin or Paris actually wants war with Russia.

Which leaves us with the other question: Is Russia bracing for war or looking for a pretext to start one?

Rojanksy repeatedly implies that America and Russia are equally responsible for the lack of mechanisms for managing the relationship. But he obviously knows, or must know, that all the dangerous incidents he referred to were caused by Russian planes, ships, or submarines. That may or may not prove that Russia harbors warlike intentions, but it definitely does not prove that America does.

More important, Russia has initiated two wars in Europe, the region of the world where Russian and American interests most overlap. The first was in Georgia in 2008; the second, still going on, was in Ukraine in 2014.

Even if you believe that both wars were started in response to NATO enlargement and the CIA’s manipulation of colored revolutions, the fact is that Russia started both, demonstrating at the very least that Russia is perfectly capable of starting and fighting wars in Europe.

Does this mean that Russia is therefore preparing for a war against America or Europe? Not necessarily. But it does suggest that Western worries about the possibility of a Russian-initiated war are not irrational.

Which brings me to my last point: Putin’s rationality and the nature of the Putin regime. Rojansky treats him and his American interlocutors as normal, rational, run-of-the-mill statesmen who should pursue confidence-building and crisis-reduction measures. He also assiduously avoids any mention of the profoundly authoritarian, hyper-centralized, repressive, and possibly fascist system constructed by Putin.

But leaders and domestic systems affect the foreign-policy behaviors of states. Irrationally inclined, hyper-masculine leaders with cults of personality are not particularly known for their pacific behavior. And authoritarian states are intrinsically more inclined to rattle sabers and start wars than democratic ones.

Western leaders should therefore fear war with Putin’s Russia. They should do everything they can to reduce the likelihood that dangerous incidents escalate. But, above all, they should do everything possible to contain Putin and bolster the defensive capacity of the frontline states: the Balts, Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia, and Kazakhstan. That may sound like cold war, but it’s infinitely preferable to Putin’s proven penchant for hot war.

Alexander J. Motyl is a professor of political science at Rutgers University-Newark, specializing in Ukraine, Russia, and the former USSR.

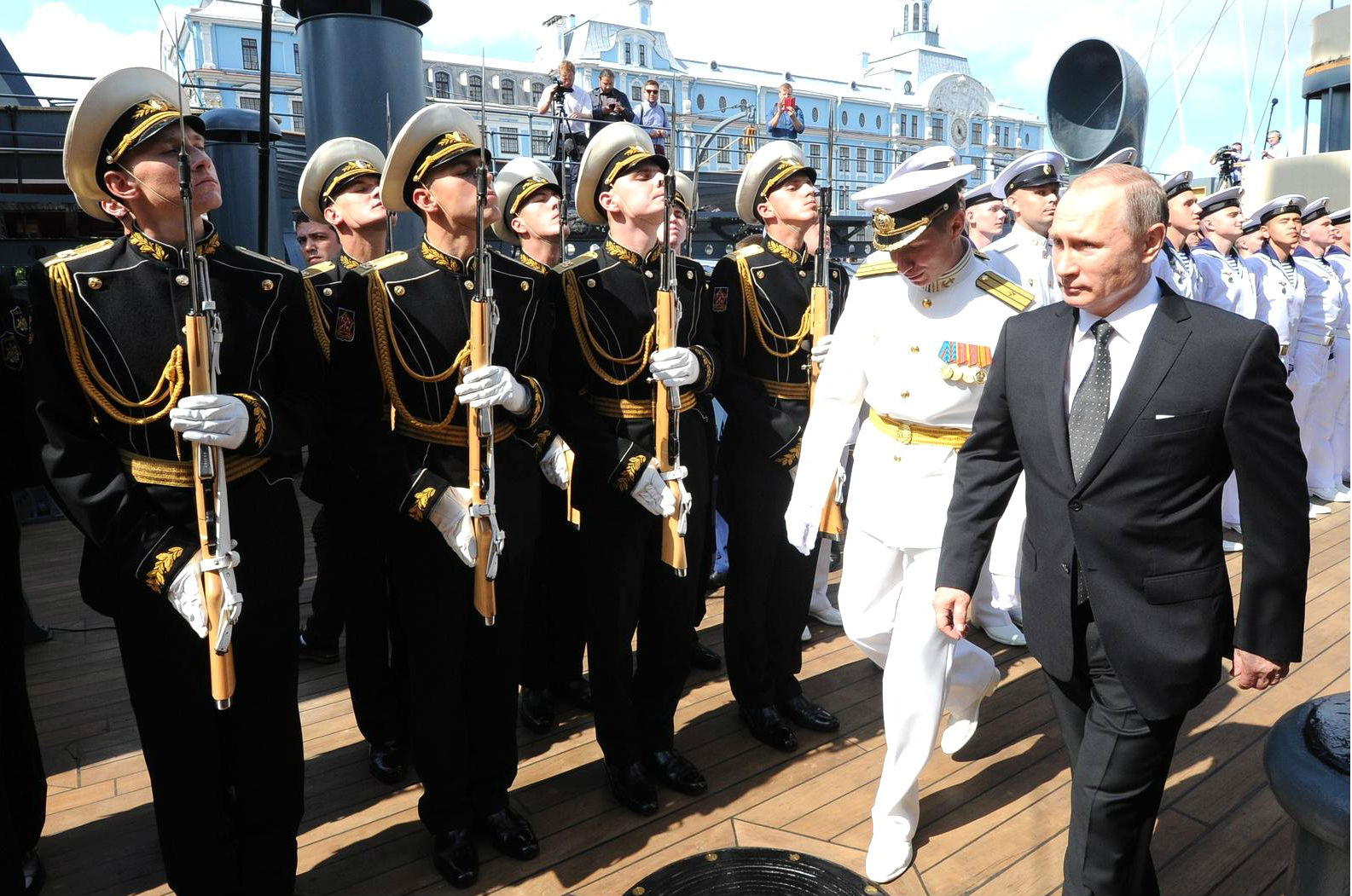

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin takes part in Navy Day celebrations on July 31 in St. Petersburg, Russia. Credit: Kremlin.ru