There is no alternative to US Treasuries

Defaulting on the debt would be disastrous for US leadership of the international financial system. The uncertainty of when the crisis would end could trigger a global recession. Over the long-term, the health of the dollar would be damaged.

However, it’s possible that investors would try to buy more US Treasuries in the wake of default. Why? Because there is no viable alternative. Think back to the start of the Global Financial Crisis or COVID-19. In both situations, the world scooped up US bonds. That’s because there is nothing else like US Treasuries.

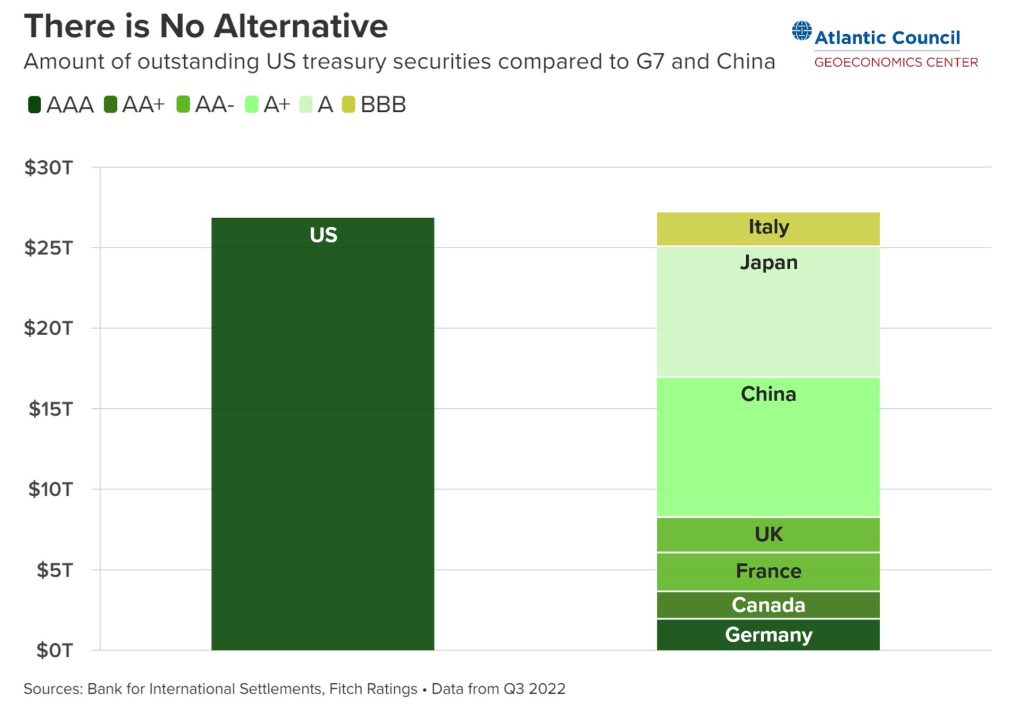

In a crisis, investors search for safety. Safe assets have a high likelihood of payout and can be traded easily. In practice, that usually means bonds issued by a handful of stable governments in advanced economies. The problem for any investor looking for safety in the wake of a US default is that the US Treasury market is much larger than any similarly-rated government bond market.

Would the world turn to German bunds, the only other AAA-rated sovereign debt in the G7? Maybe, but as the chart above illustrates, their market is less than 1/10th of the size of the US Treasury market. And German fiscal rules make it basically impossible for them to ever catch-up.

Where else to go? The UK gilt market? Beyond its small scale, you will recall the UK had its own credibility crisis just last year.

China? If you’re looking for a reliable, transparent, liquid market where you can turn your holdings into cash quickly without question, China is not it.

Japan seems like a reasonable option until you realize the amount of Japanese government bonds (JGBs) available is overwhelmingly influenced by the central bank’s intervention in its bond market.

Where else could investors turn? They could hold more cash, but the opportunity cost of doing so has risen in the form of higher interest rates. They could look for relatively safe private sector assets, like the bonds of large, stable firms. But as the crisis of 2008-09 showed, even highly-rated private sector securities can be risky in a crisis.

There simply are not enough safe assets available for investors to move off of Treasuries. This is one reason why flirting with a default is so maddening. The US government issues something the rest of the world desperately wishes it had.

In the immediate aftermath of a default, Secretary Yellen may calm the Treasury market by promising to continue to pay interest on debt even as other bills go unpaid. But no one should mistake that for a solution. There would be massive fallout both for the US and global economy in this scenario. The bottom line is that in a default, even if US Treasuries have a short-term win, everyone—including the US—will still lose.

Josh Lipsky is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and a former adviser at the International Monetary Fund.

Phillip Meng contributed research to this piece. A version of this piece appeared in the GeoEconomics Center’s private Sunday night newsletter Guide to the Global Economy. To subscribe to the newsletter, please email sbusch@atlanticcouncil.org.

At the intersection of economics, finance, and foreign policy, the GeoEconomics Center is a translation hub with the goal of helping shape a better global economic future.

Further reading

Mon, May 15, 2023

The US debt ceiling stalemate threatens money market funds—and financial stability

Econographics By Hung Tran

Money markets would be the first to react to a debt ceiling breach, heightening market turmoil at the wrong time and helping to raise the odds of a severe recession.

Mon, Mar 20, 2023

The US debt limit is a global outlier

Econographics By Mrugank Bhusari

Debt limits are not the norm in public finance. But countries that have adopted them do not let them cause economic chaos.

Mon, Mar 27, 2023

Loss of investor confidence and the banking crisis

Econographics By Hung Tran

Despite the best efforts of financial authorities following the most recent banking crisis, selloffs of bank shares and capital contingent bonds have persisted. After the sale of Credit Suisse, the most poignant example of investor concerns is the market pressure on Deutsche Bank (DB).

Image: Sunset at the Treasury Department