Serbia’s future depends on rebuilding rule of law and EU credibility

Bottom lines up front

- Serbia’s reform drive has lost steam, with corruption and political centralization eroding the rule of law and limiting growth.

- The student-led protests that began in late 2024 signal renewed civic pressure for fairer elections and stronger institutions—if they succeed, Serbia could return to its reform trajectory of the early 2000s.

- Restoring a credible path to EU accession would be the single most powerful external incentive for change, with potential spillover benefits for stability and governance across the Western Balkans.

This is the third chapter in the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s 2026 Atlas, which analyzes the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

Evolution of freedom

Serbia’s freedom trajectory since 1995, according to the Freedom and Prosperity Indexes, falls into three distinct periods. The first is the dismal 1990s, defined by war, sanctions, and international isolation; institutions hollowed out, and the political sphere narrowed to the point of collapse. The second begins with the fall of Slobodan Milošević in 2000 and runs to roughly 2011, when the country reopened to the world and took the first steps toward European integration. The third starts around 2012, when the political environment tightened again and the gains of the previous decade began to erode. This pattern is visible in the Freedom Index: a sharp improvement after 2000, followed by a gradual downturn driven overwhelmingly by the political subindex after 2012.

The post-2000 rebound was immediate and dramatic in terms of politics and economics, but the rule of law took a more gradual turn. The political opening—competitive elections, wider latitude for civil society and media, and normalization of international relations—was the most visible change. Serbia signed bilateral investment treaties and free-trade agreements with neighbors and, in 2008, concluded a Stabilization and Association Agreement with the European Union. Even though domestic politics remained turbulent—Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić was assassinated in 2003, nationalism continued as a potent force, and Kosovo’s 2008 declaration of independence sparked a backlash—the trajectory differed markedly from the 1990s. European integration acted as the anchor that pulled politics and policy toward a more open equilibrium.

In 2010, the balance of incentives changed. After the global financial crisis, the EU’s enlargement energy waned; for the Western Balkans, accession increasingly looked theoretical rather than imminent. Without a credible “carrot and stick,” the reform push slowed across the region, while in Serbia, the political environment hardened against EU integration. The timing aligns with the ascent of the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) and the rise of Aleksandar Vučić—first as prime minister in 2014 and later as president—under whom power centralized and media pluralism came under pressure. International observers like the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) became increasingly critical of the country’s internal dynamics. Civic activism—still very present—operated in a tighter space.

European integration acted as the anchor that pulled politics and policy toward a more open equilibrium.

Over the past thirteen years, the cumulative effect has been systemic: Corruption has eroded the rule of law and turned key institutions into instruments of incumbency. Elections remain formally competitive but are marked by recurrent irregularities that leave little chance for alternation. Ruling party-aligned media dominate the information space, public advertising is allocated opaquely, and the security services have targeted civil society organizations on dubious grounds. The result is a shrinking political arena in which checks and balances are increasingly performative rather than constraining.

Media pluralism has faced sustained pressure. Journalists and associations report smear campaigns, threats, and pervasive self-censorship, while access to advertising and public funds tracks political alignment. Civil society is larger and more professional than two decades ago, but its operating space has narrowed—foreign funding is stigmatized, senior officials attack prominent NGOs, and procedural burdens sap time and resources. The situation is not one of outright closure, but the cumulative friction is real.

Within the political subindex, the steepest, most persistent deterioration is in political rights—freedom of association and expression—while the elections and legislative-constraints components also weaken. The contour is recognizable: After the 2000 break, political rights jump, remain broadly stable until the early 2010s, and then trace a clear decline that, while significant, does not return to 1990s levels. Elections remain formally competitive, but the tilt in media access and state resources has grown; the legislative constraints on the executive ebb as power concentrates in the presidency.

The legal subindex tells a different story: It starts at a low point, followed by early reforms and then stasis. The first post-Milošević years saw the establishment of baseline prosecutorial and judicial reforms, but two hard problems persisted: a lack of genuine independence from the executive and the capacity to process cases in a timely, professional way. Both remain binding constraints. Serbia’s legal profile improves off its post-conflict trough and then plateaus, reflecting institutions that function day-to-day but buckle at the most sensitive interfaces with politics. The causes are structural: Building effective, impartial courts is far harder and slower than opening political space, and where EU conditionality is weak or distant, momentum lags.

The steepest, most persistent deterioration is in political rights—freedom of association and expression.

The legal upswing in the 2000s reflected real change—new courts, stronger constitutional guarantees, prosecutorial reforms, and a framework closer to European norms—and informality fell as tax bases modernized and customs enforcement improved. But judicial independence and effectiveness remained the weak links: External pressure, slow case resolution, selective enforcement in high-profile economic cases, and gaps in accountability and conflicts-of-interest rules kept trust low. Those frictions continue to drag on the economy.

Within the legal subindex, Serbia’s early-2000s bump is consistent with a shift from conflict to basic legal normalcy—laws regularized, courts reopened, and administration stabilized—with only minor oscillations later. The 2019–20 dip likely reflects the major protests triggered by the murder of opposition politician Oliver Ivanović in 2018, which led many opposition parties to boycott the 2020 elections. It also reflects setbacks in judicial reform and popular distrust in legal institutions. Constitutional amendments were eventually adopted in 2022, a move that modestly improved formal judicial independence even though implementation remains contested.

The economic subindex improves steadily from the early 2000s until the pandemic, then levels off. Its composition helps explain why. Women’s economic freedom—largely driven by statutory changes captured in the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law global report—rises markedly in the mid-2000s. Investment freedom and trade freedom also strengthen as Serbia deepens its commercial integration with the EU and broadens ties with Russia, China, Turkey, and others. Regulatory reform—streamlined procedures, clearer company law, and liberalized capital flows—improved the investment climate, while the accession process nudged alignment on services and market-access rules. New firms entered and integrated into regional supply chains in manufacturing and agribusiness, even as legacy incumbents persisted in some sectors. This is the one domain where policy has been consistently outward-oriented over the past quarter-century, even as rule-of-law reforms slowed. In effect, Serbia decoupled economic integration from institutional convergence: It became a more open, investor-friendly production platform without moving in tandem on media freedom or judicial independence. However, challenges remain in economic freedom. Property-rights enforcement and contract execution remain below EU norms—a deterrence for smaller investors. State-owned enterprises still play an outsized role in some sectors, obstructing competition and investment freedom. The use of incentives, particularly for some foreign investors, while bringing in new capital can also distort the level playing field.

The most recent political developments underscore both the resilience of civil society and the limits of the current equilibrium. Since late 2024, large student-led protests—sparked by a fatal building collapse in the city of Novi Sad and subsequent corruption allegations in the construction industry—have broadened into a sustained challenge to the status quo. The student-led movement remains within institutional politics: It aims to contest and win elections and then reform from within. Whether it can do so without direct confrontation depends on the state’s willingness to ensure a level playing field—and on the response of powerful external patrons. In the Freedom Index, the immediate consequences fall on the political subindex, but the stakes are larger: Progress in the legal subindex will require credible insulation of the judiciary from political interference, and professional policing—areas that have lagged for a decade.

Evolution of prosperity

Serbia’s prosperity profile reflects the same three phases, but the translation from freedom to outcomes is neither automatic nor linear. In the early 2000s, as political freedoms opened and the economy reconnected to Europe, income per capita rose and the country began to narrow the gap with the regional average. Then the 2008–09 financial crisis hit Serbia, though not as hard as in many EU member states—partly because Serbia was outside the euro area and partly because of its diversified trade and investment partners. The pandemic-era shock was similar: Growth dipped but recovered quickly relative to Western Europe, helped by early access to vaccines from China and less severe energy-price pass-through due to ties with Russia. The Prosperity Index’s income component captures this series of interruptions rather than collapse.

The country’s resilience is tied to its growth model. For roughly a decade, net foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows have run at about 6–7 percent of GDP, with sources increasingly diversified beyond the EU. China has become a leading investor, while Serbia has also plugged into German value chains in mid-tier manufacturing. The model is not high-tech sophistication; rather, it is steady insertion into European (and to a degree global) production networks. As long as political stability held, the arrangement delivered: jobs in export-oriented plants, a stronger tradables base, and sustained convergence. The current uncertainty—whether stability can continue without institutional reform—is therefore not an abstract governance concern but a direct question about the durability of the prosperity path.

Prosperity has more dimensions than income, and Serbia’s experience across them is uneven. Health is the sharpest outlier in the pandemic period: While output fell less than in Western Europe, excess mortality was higher, reflecting more permissive lockdowns, thinner safety nets, and health-system limits. Over the long run, health outcomes have improved, but there is still a persistent gap with richer European systems; out-of-pocket costs are high by regional standards, and hospital infrastructure trails the EU core.

Education follows a less pronounced trajectory. The baseline is decent legacy human capital—Serbia inherits strong math and engineering traditions from Yugoslavia—but the system struggles with funding and modernization. The Prosperity Index’s education component rises gradually with cohort attainment and expected years of schooling, but there is no step change akin to the post-2000 political jump. The bottlenecks are familiar: teacher pay and training, infrastructure in secondary and vocational streams, and alignment with the needs of an export-oriented manufacturing base.

On income inequality, Serbia’s path in the 2000s and early 2010s conforms to a modest Kuznets-style worsening—where inequality rises during the early stages of development—as growth resumed and labor markets restructured. That was followed by a period of relative stability and, by the mid-2010s, Serbia’s Gini index was among the higher readings in Europe, reflecting how early market liberalization often rewards upper deciles first while redistribution and competition policy lag. Today’s level is close to the mid-1990s baseline, underscoring how incomplete rule-of-law reform constrains broad-based gains. Here again, the structure of growth matters: FDI-led manufacturing and construction have provided employment and some formalization, but the gains are uneven across regions and skill levels. When investment cools—because confidence dips or political risk rises—the distributional strain is quickest to reappear at the margins.

The environment and the treatment of minorities complete the picture. In environmental quality, the legacy of coal-heavy energy and industrial emissions weighs on air quality, especially in urban centers, even as gradual gains in household energy and vehicle standards help. The Prosperity Index’s environment component records a slow improvement that is vulnerable to policy drift and external shocks. The politics of a green transition are visible in the Jadar lithium project near Loznica. Touted as a strategic growth opportunity and opposed over groundwater risks, land loss, and opacity, the mining project has swung from license revocation in 2022 to partial reinstatement in 2024, reigniting protests. The episode captures the broader dilemma: aligning investment with credible environmental standards and local consent.

On minority access, the record is mixed: Legal protections exist and the worst 1990s legacies have receded, but equal access to services and opportunities depends on local administration and enforcement capacity—precisely the legal-institutional levers that have lagged. Post-2000 reforms—constitutional protections, cultural councils, and local representation—moved minority rights closer to regional norms, especially for Hungarians, Bosniaks, and Roma, but progress has stalled since 2011. Formal guarantees remain, but politicization, uneven municipal implementation, and hostile media narratives in tense electoral periods have limited real access to services and opportunities.

The interaction between freedom and prosperity is clearest in three places. First, the post-2012 slide in political rights bleeds into the economy by weakening predictability: When media scrutiny and legislative checks soften, policy becomes more discretionary, which eventually shows up as softer investment freedom and a more erratic economic policy. Second, the state capacity problems in legal matters—especially judicial independence and effectiveness—translate into higher transaction costs, slower dispute resolution, and a bias toward insiders; these are prosperity-sapping frictions, even in an open-trade, FDI-friendly regime. Third, women’s economic freedom raises the ceiling on growth by widening the labor pool and entrepreneurial base; Serbia’s mid-2000s improvement on statutory gender equality has been a quiet contributor to its industrial catch-up. The Prosperity Index registers all three channels, but the pace and breadth of gains depend on whether the political and legal pillars reinforce or undercut one another.

The post-2012 slide in political rights bleeds into the economy by weakening predictability.

Finally, recent domestic politics inject new uncertainty into what had become a well-understood model. The student-led protests that began in late 2024 have matured into a more organized political movement seeking early elections and a reform mandate. It is clear that this crisis will not simply fade away. Any escalation will pose serious questions for both Serbia’s democratic trajectory and the wider Western Balkans, where progress on rule of law, civic rights, and European integration remains fragile.

Investors are studying these signals closely. Already, foreign direct investment has fallen sharply: in the first five months of 2025, net FDI inflows amounted to roughly €631 million, compared with about €1.943 billion in the same period the year before—a drop of around 67.5 percent. If the political outcome is a genuine leveling of the electoral playing field and a credible push on rule-of-law reforms, Serbia’s prosperity path could re-accelerate—foreign capital is mobile and already present at scale. But if confrontation mounts, early elections are denied, and external patrons from China and Russia harden their positions, the risk is a prolonged standstill with wider regional repercussions.

The Prosperity Index is a lagging indicator here, but its income and inequality components will tell the tale in the next few readings.

The path forward

Serbia’s way forward is not mysterious, but it will be hard. The growth model that delivered catch-up—trade openness, diversified investment partners, and insertion into European value chains—remains viable. But it is probably not going to deliver the same amount of growth in an increasingly fragmented global economy facing higher tariffs and a global slowdown in FDI. And preserving it now requires political and legal reforms that were postponed when the EU accession horizon receded. The central insight of the last decade is that while economic integration can be decoupled from institutional convergence for a time, it cannot be decoupled indefinitely. The Freedom Index already shows the cost of delay in the political subindex, and the longer the legal subindex lags, the more the prosperity gains will flatten.

It is clear that this crisis will not simply fade away … escalation will pose serious questions for both Serbia’s democratic trajectory and the wider Western Balkans.

The immediate priority is political. Elections must be not only formally competitive but substantively fair, with balanced media access and a clean separation between state resources and party campaigning. Legislative oversight should recover ground lost to executive centralization; if the presidency remains dominant, courts and parliament cannot perform their checking functions. Serbia’s civil society has shown it can mobilize against overreach; the question is whether that energy can produce institutional change without confrontation. A credible commitment to level competition would register quickly in the political subindex—especially in elections and political rights—and, with a short lag, in investment sentiment.

The second priority is legal. Serbia needs a judiciary that is both insulated and empowered. Independence requires appointment and promotion systems that minimize political leverage; effectiveness requires resources and management that accelerate case processing and professionalize court administration. The legal subindex’s components offer a checklist: Clarify laws and reduce contradictions; strengthen judicial independence and effectiveness; improve bureaucratic quality while tightening corruption control; maintain security without eroding civil liberties; and treat informality not as a statistical curiosity but as evidence of high transaction costs that can be lowered. Even modest improvements would be catalytic: When firms expect fair, timely adjudication, they invest more and formalize faster, amplifying the earlier economic gains due to trade and investment liberalization.

Sound economic policy should aim to keep what works and fix what jeopardizes it. The external stance—openness to EU markets, continued diversification of partners, and predictable treatment of foreign investors—has served Serbia well. But stability established by way of muted scrutiny is running out of road. A rules-first approach to fiscal policy, procurement, and state-firm relations would lower the risk premium without forcing a retreat from the country’s pragmatic geoeconomic posture. In this sense, the economic subindex’s strongest components—trade, investment, and women’s economic freedoms—are the baseline to protect, while property-rights enforcement and corruption control are the levers for raising the ceiling.

Prosperity policy should target slow variables that pay off across cycles. Health outcomes require steady investment in primary care, hospital equipment, and public-health capacity; the pandemic showed how quickly gaps widen when systems are overrun. Education needs a dual track: modernized general schooling and a serious vocational stream matched to the country’s role in regional value chains. Inequality is best tackled by sustaining labor-intensive FDI while pushing more value added into local supply chains; when more of the “last mile” of production happens domestically, wage gains spread. Environmental quality will improve when energy policy tilts toward cleaner sources and when industrial standards rise; here, alignment with EU norms is both feasible and, over time, growth-enhancing. The Prosperity Index components—health, education, inequality, environment, minorities—will move together if legal quality does its part.

Geopolitics will keep testing Serbia’s pragmatism. The country’s relative nonalignment among major powers has so far produced diversified capital and insurance against shocks. The risk is that a domestic political crisis or external confrontation would force sharper choices. The safest way to preserve room for maneuvering is institutional: Fairer elections, stronger oversight, professional courts, and trustworthy administration lower the temperature at home and raise trust abroad. Investors do not require perfection; they require predictability. The Freedom Index’s political and legal pillars are proxies for that predictability, and progress there will determine whether the Prosperity Index resumes its upward slope or plateaus.

Reenergizing the EU accession track would have effects well beyond Serbia’s borders. Because Belgrade sits at the center of the region’s unresolved files—above all, relations with Kosovo and the major constitutional and territorial agenda in Bosnia and Herzegovina—building Serbian stability would lower regional tensions. A visible move from Belgrade to a more committed EU path would lower the political risk premium, unlock stalled dossiers, and revive the demonstration effect that powered reforms in earlier enlargement waves. The spillovers would be tangible—more predictable rules, faster dispute resolution, clearer procurement—and would draw in investment that binds the region more securely to European value chains. In short, if Serbia moves, the region moves; if Serbia stalls, momentum will move elsewhere in the region.

A recommitment to Serbia’s EU integration is possible. The region offers examples of rapid legal improvements when potential EU accession is real and monitored; Serbia’s own economy shows how quickly openness pays when credibility is present. What has been decoupled can be recoupled: political pluralism that is not merely formal, legal institutions that function without fear or favor, and an economy that remains as open and diversified as the past decade but under rules that are clearer and more evenly enforced. If that alignment is restored, the next readings should show the familiar pattern in reverse: first, stabilization of political rights and elections; next, a nudge up in legal quality; then, renewed momentum in investment and trade freedom—followed by broader prosperity gains that are felt not only in GDP charts but in health clinics, classrooms, and paychecks.

about the author

Richard Grieveson is deputy director at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies and a member of the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group. He coordinates wiiw’s analysis and forecasting of Central, East and Southeast Europe. In addition he works on European policy analysis, European integration, EU enlargement, economic history, and political economy.

He holds degrees from the universities of Cambridge, Vienna, and Birkbeck. Previously he worked as director in the Emerging Europe Sovereigns team at Fitch Ratings and regional manager in the Europe team at the Economist Intelligence Unit.

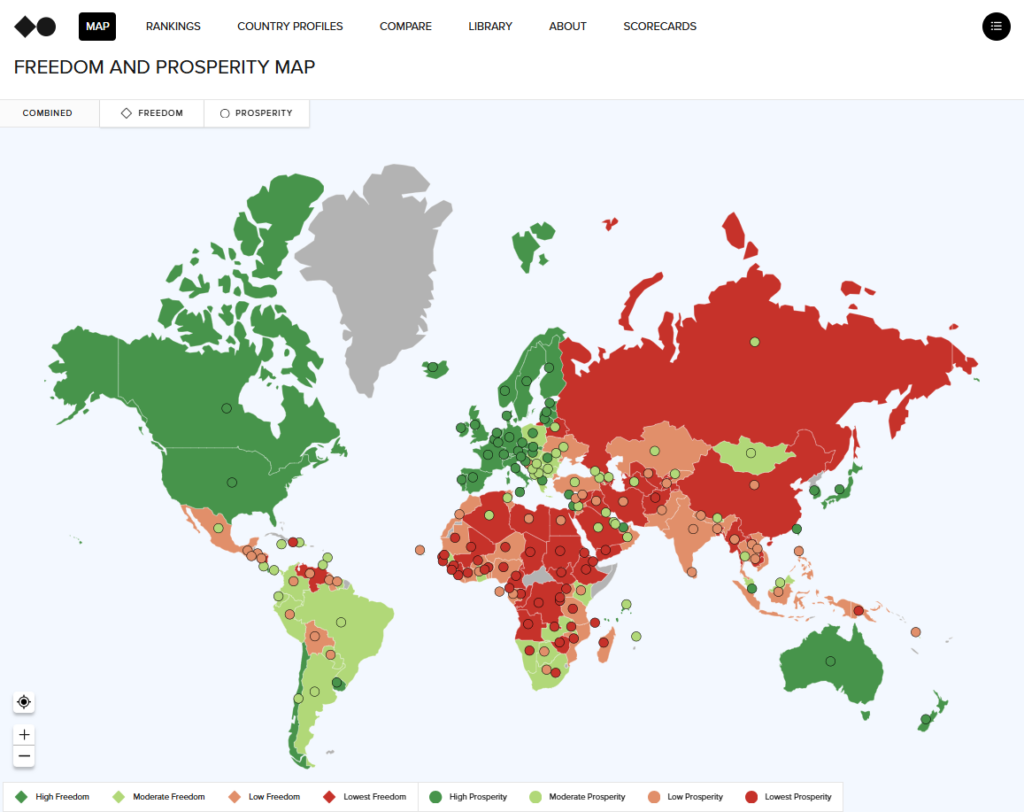

Explore the data

The Indexes rank 164 countries around the world. Use our site to explore thirty years of data, compare countries and regions, and examine the subindexes and indicators that comprise our Indexes.

Stay Updated

Get the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s latest reports, research, and events.

Stay connected

Read all editions

2026 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Against a global backdrop of uncertainty, fragmentation, and shifting priorities, we invited leading economists and scholars to dive deep into the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries around the world. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

2025 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists, scholars, and diplomats analyze the state of freedom and prosperity in eighteen countries around the world, looking back not only on a consequential year but across twenty-nine years of data on markets, rights, and the rule of law.

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Image: People buy dried oak leaf branches and wheat, symbols of the traditional Yule log, in Belgrade January 5, 2012. REUTERS/Ivan Milutinovic

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media