Syria’s Kurds could be al-Sharaa’s partners in rebuilding. Why did Damascus assault them instead?

Among the unsung success stories of Syria’s transition after the fall of Bashar al-Assad were two agreements between the interim government in Damascus and Syrian Kurds—rare examples of peaceful compromise in a year marked by sectarian killings of other minorities, including Alawites and Druze.

The March 10 agreement between Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) commander Mazloum Abdi and interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa was intended to integrate the SDF into the new Syrian army. The Aleppo Agreement, signed in Syria’s second largest city in April, was the first practical implementation of the March 10 agreement, because it entailed the integration of local police forces: the Kurdish Asayish and Internal Security Forces linked to the interim government.

When I visited Aleppo several months after that agreement was signed, it was still largely holding. I interviewed Hefin Suleiman and Nouri Sheiko, the two Kurdish signatories of the agreement, as well as officials from the Aleppo governor’s office. Both sides were committed to continuing to work together.

I also met a dozen Kurdish and Arab women in the Sheik Maqsoud Women’s House. The new flag of the Syrian government was on display in their spacious office. They told me proudly how they had applied for—and received—official permission to operate as a non-governmental organization (NGO) from Minister of Social Affairs and Labor Hind Qabawat, who is also the only female minister in the cabinet of the interim government in Damascus. They were genuinely eager to work with her and were planning a conference for women all across Syria. These Kurdish women in Sheik Maqsoud were literally working with Damascus down to the minutiae of complying with their rules and regulations for NGO registration. They, too, appeared committed to the Aleppo Agreement.

The Kurdish Asayish and Arab Internal Security Forces were already operating shared check points in Aleppo. In October, the SDF has submitted a list of their commanders who could serve in the Ministry of Defense in Damascus, as part of integration talks. And in other parts of Syria, the SDF and certain units of the new Syrian army aligned with Damascus had already begun coordinated activities under US supervision, as I learned during fieldwork in Syria in December.

But on January 6, Damascus launched an assault on Aleppo.

Some 150,000 people were displaced just in two days of fighting, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. An estimated 1,200 Yezidi families were caught up in the fighting, some of whom were resisting what Iraqi Member of Parliament Murad Ismael described as a “brutal attack” by the factions of the Damascus authorities.

Why did al-Sharaa launch an assault on the very people with whom he had signed not one, but two agreements? What went wrong?

A stalemate in negotiations

Both agreements were due to quiet US diplomacy. It was hoped they would help reunify the fractured country after over a decade of conflict.

US mediation efforts have been led by Tom Barrack, who is dual hatted as the US ambassador to Turkey and also special envoy to Syria. The mediation was a tough job, but it had already achieved important progress. The two sides did not trust each other, having fought against each other in the past. Al-Sharaa is the former commander of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which evolved out of Jebhat al-Nusra, an al-Qaeda offshoot. In an earlier phase of the war, Jebhat al-Nusra had fought against Syrian Kurds in the Kurdish People’s Defense Units, or YPG (the predecessor of the SDF).

This distrust was only compounded after sectarian killings of Alawites in the coastal regions in March, and then another round of killing in the Druze stronghold of Sweida. A Reuters investigation of the massacres of Alawites found that the “chain of command led to Damascus.” A United Nations investigation into the events in Sweida is still ongoing.

Kurds had reason to be skeptical of the new authorities in Damascus. After assuming power in Damascus, al-Sharaa has promoted several rebel leaders into positions of power who have been sanctioned by the United States for serious human rights violations. They include two notorious warlords. Sayf Boulad Abu Bakr, who had been sanctioned for kidnapping Kurdish women and abusing prisoners, was promoted to commander of the Seventy-Sixth Division overseeing Aleppo. And Mohammed Hussein al-Jasim, known as Abu Amsha, was promoted to lead the Sixty-Second Division in Hama. The US Treasury estimated that his militia generated tens of millions of dollars a year through abduction and confiscation of property in Afrin, where Turkey maintains a large security presence.

But Kurds were under significant US pressure, and the Syrian Kurdish leadership is pragmatic.

Furthermore, Kurds in Aleppo had survived under siege and managed to preserve control of the Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyah neighborhoods throughout the civil war. Now Assad was gone and al-Sharaa had made verbal promises about Kurdish rights—although no constitutional guarantees until now. So in April the Kurds agreed to withdraw their military forces from Aleppo and only maintain police forces, which would also fully integrate with the Syrian government’s police forces.

In other words, they agreed to place their trust in Damascus, knowing they would have no military forces of their own once the SDF withdrew—knowing they would be surrounded on all sides. For years, the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration has controlled a vast oil-rich region in the northeast, but it is not geographically connected to Aleppo.

The Aleppo Agreement in April was celebrated as a success story by both sides.

The Aleppo offensive, hate speech, and disinformation

Leading up to and during the government’s offensive in Aleppo and eastern Syria in January, there was an alarming rise of anti-Kurdish hate speech and disinformation, as well as more subtle attempts to undermine the SDF.

For example, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Interior in Damascus, Nour al-Din Baba, referred to them as the “so-called SDF” in an interview with Al Jazeera in late December. In the initial days of the Aleppo offensive, false news was circulated claiming that SDF commander Mazloum Abdi had said that the SDF intended to “fully recapture all of Aleppo.” Verify Syria debunked this as disinformation. In reality, the SDF had agreed to withdraw and had never controlled all of Aleppo to begin with. Less than a week later, a video clip was circulated on social media claiming to feature a former officer of the Assad regime who was positioned alongside the SDF in Deir Hafer. Verify Syria documented that it was a fake video generated using AI techniques.

The armed groups who carried out the assault on Aleppo have made their own videos where they refer to Kurds as “sheep” or “pigs” and posted them on social media. In one particularly horrific video, which has since been verified, the corpse of a woman was thrown out of a building as men celebrated and chanted Allahu Akhbar. The Kurds identified the woman as having been a member of the Internal Security Forces—according to reports—the very police force created by the Aleppo Agreement.

The Aleppo violence is even more tragic because Damascus and the SDF were on the verge of a larger national agreement to integrate their forces.

According to reporting by Al Monitor, it was Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad Hassan al-Shaibani who interrupted the last round of US-brokered talks on January 4 between the SDF and Damascus. After abruptly entering the room, he asked that US Brigadier General Kevin Lambert leave the meeting, and promised that the talks would resume on January 8.

But before talks could resume, Damascus launched its assault on Aleppo on January 6.

Moving forward

On January 10, Barrack called for a return to the March 10 and Aleppo agreements. Turkish Ambassador to Syria Nuh Yilmaz said he also welcomed the return to the Aleppo Agreement, which allows for local governance in the two Kurdish neighborhoods.

In the days that followed, al-Sharaa’s forces continued their offensive against SDF-held areas, capturing large parts of Raqqa and Deir Ezzor, areas the SDF had held after defeating the Islamic State. On January 17, US Central Command Commander Admiral Brad Cooper called on al-Sharaa’s forces to “cease any offensive actions.” But the offensive continued.

As al-Sharaa’s forces moved east, chaos ensued and numerous detention facilities housing Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) militants were opened. According to one report, at least four separate detention facilities were opened, which collectively held some 33,500 ISIS militants. It remains unclear how many have escaped.

Forces aligned with Damascus have also taken videos of themselves desecrating SDF cemeteries in Hasakah in the northeast, an area controlled by the SDF for many years.

Understanding the origins of the violence in Aleppo is critical. While each side blames the other for the escalation, a full investigation will be needed to establish the facts. But it is equally important to examine the underlying conditions that made this eruption possible.

The Aleppo Agreement was proof that both decentralization and integration could work in practice.

Damascus had agreed that the two Kurdish neighborhoods in Aleppo could continue to provide their own local security, could continue to offer Kurdish language instruction, and that women could continue to serve in the police—just not at shared checkpoints with men. Both sides agreed to all of this, illustrating that the two major power blocs could come to a peaceful compromise and coexist. This set an important precedent for how other contested regions of Syria could potentially be integrated.

But Turkey remains influential in these negotiations. As early as 2015, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan had said he will “never allow” a Kurdish statelet in Syria. After the fall of the Assad regime, he has continued to publicly state his opposition to the continuation of Kurdish-led local governance or decentralization in Syria. Al-Sharaa’s desire to assert control over all Syrian territory appears to have aligned with Erdogan’s own opposition to Kurdish self-rule. Furthermore, Erdogan may believe that by dealing the SDF another blow, that he can extract greater concessions from the peace process with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The PKK is a US and EU designated terror organization. The SDF is dominated by the People’s Defense Units (YPG), which Turkey views as an offshoot of the PKK.

On January 16, al-Sharaa announced a presidential decree “affirming the rights of Syrian Kurds.” While this is an important step, it could also be easily revoked by another presidential decree. Meanwhile, al-Sharaa’s forces continued their offensive into Kurdish-held areas. On January 18, a four-day new cease-fire agreement was announced. It has since been extended by another 15 days. This new timeline is divorced from the new realities on the ground.

Rebuilding trust will be even harder than before, and will take time.

Proper vetting of the various armed factions will also take time. The Islamic State militant who killed three US troops in December was a member of the Syrian government’s security forces. Al-Sharaa should prioritize rooting out jihadists from within his own ranks, rather than attempting to seize more territory and subjugate minorities.

Instead of pressuring the SDF to integrate on a rushed timeline that carries serious risks, President Trump should pressure al-Sharaa to remove sanctioned warlords from his army and guarantee equal citizenship rights for all Syrians. Al-Sharaa must accomplish this through a constitutional guarantee, not a presidential decree that could be easily revoked.

Amy Austin Holmes is a research professor of international affairs and acting director of the Foreign Area Officers Program at George Washington University. Her work focuses on Washington’s global military posture, the NATO alliance, non-state actors, revolutions, military coups, and de-facto states. She is the author of three books, including most recently, “Statelet of Survivors: The Making of a Semi-Autonomous Region in Northeast Syria.”

Further reading

Tue, Jan 13, 2026

Eight questions (and expert answers) on the SDF’s withdrawal from Syria’s Aleppo

MENASource By

Our experts unpack why violence erupted, what it means for Kurdish safety and integration in Syria, and how Washington is engaging.

Wed, Sep 24, 2025

Is a new era of Turkey-Syria economic engagement on the horizon?

MENASource By

The convergence of Turkey's and the Gulf's economic strategies in Syria presents an opportunity for Washington.

Sun, Dec 7, 2025

One year after Assad’s fall, here’s what’s needed to advance justice for Syrians

MENASource By

The second year of a post-Assad Syria requires structural reform, victim-centered leadership, and international reinforcement.

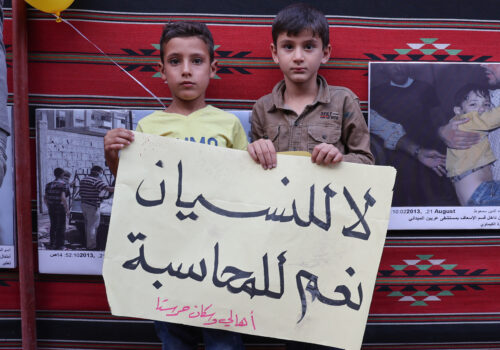

Image: Syrian Kurds attend a protest in solidarity with the people in the neighborhoods of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh in Aleppo, in Hasakah, Syria January 7, 2026. REUTERS/Orhan Qereman