The Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) tournament that took place around the turn of the year was record breaking. It drew 1.3 million fans to stadiums across Morocco and generated a 90 percent surge in commercial revenue compared to the previous tournament. Globally, it raked in record viewership numbers.

Both Senegal and Morocco rank among FIFA’s global top twenty, with high expectations heading into this summer’s World Cup in North America. Yet decades after Brazilian soccer legend Pelé predicted an African nation would win the World Cup by 2000, African soccer has not fulfilled its potential.

Soccer represents Africa’s most potent soft power asset and largely untapped economic engine, generating $625 million in 2025. Major powers have recognized African soccer’s strategic value: China has invested in around ninety Sub-Saharan African soccer stadiums since the 1960s, including $600 million on four facilities in Angola. Qatar spent more than one billion dollars on its Aspire Academy and launched Football Dreams, the largest talent search in soccer history, scouting millions of African youth for potential star players.

African players feature prominently in leagues around the world, in part because Africa has exported thousands of professional footballers, with Nigeria and Ghana leading. As of 2022, more than five hundred African players were competing in European leagues—approximately 6 percent of all elite-tier footballers in these leagues. African players are particularly prevalent in France, representing at least 25 percent of France’s Ligue 1 rosters. After a $94-million transfer to Manchester United in 2025, footballer Bryan Mbeumo (who was born in France but represents the country of his heritage, Cameroon) became one of the most expensive African players ever.

Yet this extraordinary talent pipeline coexists with systemic dysfunction. About 30 percent of players at this year’s AFCON were born outside Africa. An estimated 80 percent of talented African youth migrate to Europe before age eighteen, with African clubs earning just 0.1 to 1.1 percent of global transfer revenues as of 2022. Domestic league attendance has plummeted—Ghana Premier League attendance, for example, declined from an average of more than ten thousand per game in the early 2000s to fewer than eight hundred in 2023, while millions of fans in Ghana watch European leagues.

The root causes are economic extraction and governance failure. The African Football Confederation generated just $9.4 million in profit in the 2023-2024 financial year from a total revenue of $166.4 million—dwarfed by the Union of European Football Associations’ $208 million in profits from $6.8 billion in revenue. Domestic leagues, therefore, lack capital for infrastructure or talent retention. Instances of corruption and mismanagement have eroded fan trust. Young players often see no viable path to stardom within Africa, creating a vicious cycle where talent and capital flight weakens domestic leagues.

Additionally, while the Premier League in England and La Liga in Spain dominate African airwaves, African leagues suffer from poor technical quality and infrastructure. What’s more, viewer attention spans are growing shorter, and more interactive sports offerings (such as fantasy leagues and avenues to engage directly with athletes) are competing for watchers’ time, drawing them away from typical hours-long broadcasts. Viewers just aren’t engaging with African soccer in the ways they used to: For context, in Africa, 91 percent of people who streamed videos such as sports did so on phones rather than stationary devices such as laptops. But this is an opportunity for the continent; it could pioneer a new soccer product for the digital age.

The continent could reinvigorate African soccer with a new “Global African League” that adapts to the streaming and engagement habits of Africa’s young—and growing—population. It can do so by emulating the Kings League in Spain, which focuses on digital-first entertainment. It includes seven-a-side games lasting forty minutes, in addition to features that make the games more accessible and dynamic for viewers: For example, creative fan-voted rules and free streaming on YouTube, TikTok, and Twitch. The 2023 inaugural Kings League season generated 47 million hours of streaming, attracted major sponsors, and expanded to Brazil, Italy, France, Germany, and the Middle East. African legends such as Didier Drogba could become club presidents with participatory fan ownership models, mirroring how Neymar and Sergio Agüero have stepped into Kings League roles.

Enthusiasm for this new format could drive the creation of thousands of new jobs across Africa’s booming billion-dollar creator economy. Operating outside traditional soccer governance structures, a Global African League could generate revenue needed to reinvest in grassroots talent—offering African youth a viable path to stardom at home, stemming the exodus that has hollowed out domestic leagues.

Exhibition matches featuring diaspora stars could also attract huge global streaming audiences—in turn unlocking sponsorship from global brands and opportunities for in-game purchases or live e-commerce with mobile money integration for the continent’s 600 million users. Major African telecoms like Vodacom, MTN, and Safaricom could bid for streaming rights, integrating matches into their data subscriptions and offering free streaming to subscribers.

African entrepreneurs, telecoms, and investors should seize this opportunity to generate jobs and revenue. By doing so, they can demonstrate that Africa can innovate for the digital age, building world-class sporting competition and soft power on the global stage.

Tom Bonsundy-O’Bryan is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center, the author of Football, War & Peace, and Meta’s global affairs policy manager.

Further reading

Thu, Dec 4, 2025

How the United States can harness its sports diplomacy moment, as the FIFA World Cup nears

New Atlanticist By Katherine Golden

Foreign diplomats, US officials, and figures from the world of soccer gathered at our studios to talk about the power of sports diplomacy.

Wed, Jul 16, 2025

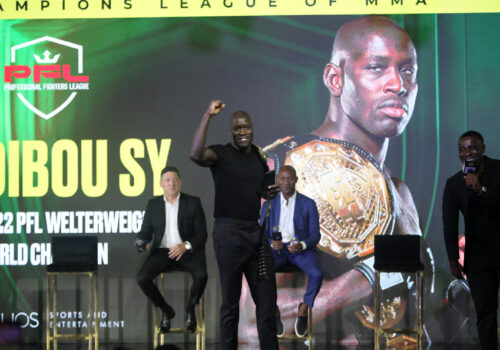

MMA’s arrival in Africa could transform opportunity for the continent’s youth

AfricaSource By

Africa is no longer just a source of talent but increasingly a hub for global sports investment and innovation.

Mon, Jun 30, 2025

Africa’s game revolution is loading

AfricaSource By Tom Bonsundy-O’Bryan

With the right investment, infrastructure, and visibility, Africa won’t just be a player in the global gaming industry—it will be the one pushing it forward.

Image: December 18, 2021 Algeria fans watch the game on their phone REUTERS/Ramzi Boudina