States shouldn’t waste the chance to establish a Syria Victims Fund

The fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria in December 2024 created once-in-a-generation opportunities for the victims of all the actors in the conflict, not only to more easily pursue accountability for human rights violations but also to better assist those who suffered undue harm. While the transitional government’s plan for a comprehensive transitional justice process is still being developed, victim and survivor communities need immediate support.

States and international organizations—including the United States, European Union, United Nations, and Gulf Cooperation Council, among others—have a vital role to play in Syria’s reconstruction and recovery, including for the hundreds of thousands of Syrians who suffered detention, torture, and abuse. But states have been responding to the conflict since its start in 2011 by initiating legal actions related to international law violations occurring in Syria. These included prosecuting companies for providing material support to terrorist organizations in Syria and imposing fines for breaching sanctions imposed in response to the conflict in Syria. From these settlements and judgments, states collected or seized significant sums—over $600 million in one instance. While the ongoing harms suffered by Syrians underpinned these cases, states have generally directed the recovered funds to their own treasuries, even as Syrians continue to desperately need international assistance to move on from over a decade of conflict.

States always had the opportunity to divert these funds to victims and survivors within Syria, but doing so while the Assad regime controlled vast portions of the country would have been complicated. Now, as states settle into their relationship with the interim government in Damascus, they should redirect the penalties they’ve collected to the underlying victims who were directly harmed. This support should be facilitated through an intergovernmental Syria Victims Fund—a mechanism for states to transfer Syria-linked funds collected from monetary judgements to a central location to better support victims of international law violations in Syria. The Strategic Litigation Project and a working group of Syrian civil society representatives have been advocating for such a fund for the past several years.

Urgent needs in Syria remain

For victims and survivors of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other human rights violations in Syria, the fall of the Assad regime marked a turning point in Syria’s history and an end to fifty-three years of state-enforced repression. It also presented significant opportunities—namely, increased access by international organizations and observers to those in need of assistance in previously inaccessible areas of the country. Both international and domestic human rights defenders and humanitarian workers have already begun administering legal and medical aid to victims and survivors living in former regime-controlled areas, and investigators have begun cataloging former detention sites and exhuming mass graves to identify the bodies recovered. Regime records are helping identify the fate of those missing.

However, the country still faces dire needs across all sectors to recover from the past decades of conflict and repression. States, international organizations, and civil society moved swiftly to support Syria after Assad fell —including lifting sanctions and providing millions in aid—but a year of aid remains insufficient in the face of decades of grievous harm, especially in light of US foreign aid cuts. While many Syrians across the country face similar humanitarian needs—such as a lack of medical, legal, or education support, the danger of unexploded ordinances, and general reconstruction in many areas devastated by the conflict—victim and survivor communities across Syria face unique challenges.

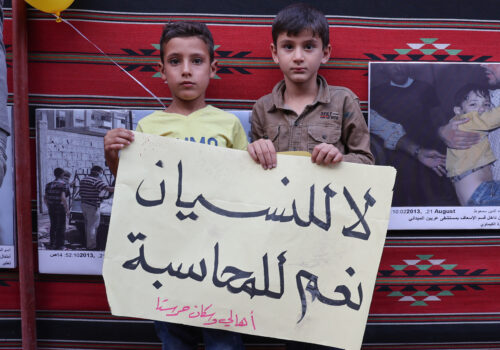

Thousands of regime detainees (who were often arbitrarily detained and subject to torture and other violations) freed from Assad’s brutal prison system—such as Sednaya prison, which has been referred to by Syrians as a “human slaughterhouse”—now need assistance in rebuilding their lives. These freed detainees, and other survivors of the hundreds of thousands of Syrians subject to regime detention, torture, and other abuses, require specialized medical care. Survivors and families of the over 500,000 Syrians believed to have been killed and of the over 100,000 believed to have been forcibly disappeared additionally require specialized psychosocial, legal, and other related aid.

Opportunities for asset collection

As Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) forces moved toward the Syrian capital in December 2024 in a rapid offensive across the country, regime officials—including financial administrators, leaders of state security forces, and Assad himself—fled the country in droves. Many are known or believed to have relocated their valuables and portable assets out of Syria or to have fled to the jurisdictions where they had stashed their wealth before Assad fell. Investigators should now follow the trails of evidence left behind to identify and collect these private assets.

Experts such as those at intelligence firm Alaco have indicated their long-held belief that the Assad family’s and associates’ wealth—largely accumulated through drug trafficking, corruption, and market manipulation—is in tax havens abroad. Many high-ranking government, military, and business officials connected to the regime fled to Russia to escape rebel forces. Others simply disappeared, along with millions of dollars collected through corruption and money laundering. Financial Times investigators have already uncovered troves of documents and intelligence related not only to the years of illicit wealth accumulation and the financing of human rights abuses but also to where Assad and his associates may have moved their ill-gotten wealth as they fled.

Related reading

According to reporting from Reuters, as opposition forces closed in on Damascus, Assad transported significant wealth to the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—including at least fifty thousand dollars in cash, as well as documents, laptops, and artwork. Reuters reported that the assets moved to the UAE reportedly included financial records, real estate, and partnerships, and details of cash transfers, offshore companies, and accounts.

Documents and intelligence recovered by HTS forces after the fall of the regime additionally revealed previously unknown dealings between prominent Syrian businessmen and the Syrian state, including millions poured into the infamous Fourth Division of the Syrian Arab Army, known for committing severe human rights abuses and stealing from the civilian population during the war.

States should now dedicate resources to identifying ill-gotten assets in their jurisdictions, pursuing legal processes to seize the funds, and repurposing them for disbursement to the Syria Victims Fund. Pursuing these actions prevents private actors from profiting off atrocities and creates an easy and sustainable pathway for states to support Syrian victims and survivors.

While assets moved to authoritarian states such as Russia may be difficult to recover, international investigators should dedicate resources to analyzing recently revealed information and recovering this ill-gotten wealth from states with asset recovery frameworks in place. Legal teams have in the past successfully secured asset freezes linked to the Assad family’s misconduct in Syria—for example, the collection by a Spanish court in 2017 of the assets of Rifat al-Assad, the uncle of Bashar al-Assad.

The need for a Syria Victims Fund

The Syrian interim government is developing a state-led transitional justice plan through the recently established National Commission for Transitional Justice and the National Commission for the Missing. This is welcome news, and the interim government must continue its efforts to work with Syrian civil society, victims and survivors, and others to create a comprehensive and representative plan. However, the urgent needs for victim communities in Syria necessitate an immediate response, and the Syria Victims Fund can fill this gap.

It must be noted that the Syria Victims Fund would not take the place of reparations, which will come through transitional justice processes. As has taken place in other post-conflict countries, such as Colombia, the Gambia, and Guatemala, reparations have the potential to restore victims’ dignity, acknowledge the harms which took place, and help victims to rebuild their lives—though only with input from survivors and affected populations can reparations programs be truly sustainable and restorative.

Instead, the Syria Victims Fund could draw on prior examples of repurposing seized funds, such as the BOTA Foundation in Kazakhstan. It could repurpose funds that morally belong to Syrian victims and survivors—in that they were seized in legal processes related to serious violations of international law in Syria—to provide interim reparative measures to victims, therefore equipping survivors with resources to seek the care that they want or need. The Syria Victims Fund’s efforts—such as working with victim communities and identifying needs—can also help facilitate transitional justice processes, such as by mapping violations or creating victim registries.

The creation of a Syria Victims Fund can help facilitate repair and recovery for Syrian victims, one year after the fall of the Assad regime. States shouldn’t waste this opportunity.

Kate Springs is a program assistant in the Strategic Litigation Project at the Atlantic Council. Previously, she was a young global professional with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center & Middle East Programs.

Celeste Kmiotek is a staff lawyer for the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Litigation Project. Her work focuses on corporate accountability and addressing the financial aspects of atrocities such as the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria, as well as legal efforts to hold the Islamic Republic of Iran to account for its domestic, transnational, and transboundary crimes.

Further reading

Sun, Dec 7, 2025

Syria’s civil society must take center stage in reconstruction

MENASource By

One year since Bashar al-Assad’s fall, Syria stands to have the most potential to showcase how local ownership can accelerate reconstruction.

Wed, Sep 17, 2025

In landmark Syria elections, women still face electoral hurdles

MENASource By Marie Forestier

As the indirect electoral process begins, Syrian officials could take several steps to increase women’s chances in this process.

Fri, Feb 24, 2023

How legal actions against Russian aggression in Ukraine can serve as a model for other conflicts

New Atlanticist By Celeste Kmiotek, Lisandra Novo

There is an unprecedented number of investigations and accountability efforts under way in response to Russia's invasion. It's a sign of success—but it also shows how victims of international crimes have unequal access to justice.

Image: Ibrahim Daraji, who said he is still mourning two sons, one lost to a mortar strike in Al-Yarmouk camp and another disappeared into Sednaya prison, shows a photo of his son Ibrahim, that hangs on the wall of his house at al-Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp, after fighters of the ruling Syrian body ousted Bashar al-Assad, in Damascus, Syria December 22, 2024. REUTERS/Zohra Bensemra