Today François Hollande has taken office as president of the French Republic. He has pressing priorities in his next five weeks but also a chance to make history in the next five years.

Tonight he sees the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, in Berlin. Hollande has said that he values the French-German couple but does not believe in duopoly. He can start now to lay the basis for a more inclusive Europe, not one in which Germany is up, Greece is down, and Britain is out.

At the G8 and NATO meetings later this week Hollande will confirm that French troops will leave Afghanistan by the end of 2012, a year earlier than previously planned. He can also propose an allied framework for Afghan reconstruction thereafter, with France in a leading role.

In June, Hollande’s Socialist party should receive a majority in the National Assembly. It would then control both houses of Parliament as well as a majority of French regions, towns, and cities. This would indeed give Hollande a mandate to govern.

Hollande can then turn to his priorities over the next five years.

As a Socialist, Hollande is better placed than any French president in decades to achieve labor market reform, provided he packages it as the empowerment of employees rather than the trampling of tradition.

With respect to the European Union, the French constitution offers Hollande as president a firm base from which to articulate a vision for a Europe oriented toward growth, fairness, and prosperity for all its members and neighbors, not just the countries of the Eurozone. (And bear in mind that if a country, like Greece, were to leave the euro, it would not in so doing secede from the EU.)

At a broader international level, Hollande can and should assert French leadership by borrowing unhesitatingly from the playbook of his predecessor: reform of international institutions, a responsible international agreement on climate change, and a global development agenda.

But perhaps Hollande’s greatest opportunity is not just to exercise power as head of the French state but to use his position as president to mobilize the French nation.

The French need to bridge two gaps that do not afflict other peoples. First, there is a huge distance between the near-mystical notion of “eternal France” and the day-to-day reality of the French — and that too easily removes from the French the burden of the destiny of France.

Second, there is a widening gap between the French and the world. For centuries, any cultivated person was meant to know the French language and therefore some French philosophy, culture, and history. That ceased to be true at the end of the Cold War. If the world no longer beats a path to the door of France, the French in France must open themselves to the world.

Hubert Védrine, the veteran Socialist wise man, has pointed to the deep discomfort that the French feel when faced with globalization. As one expert has put it, what the French fear is “a world without France.”

Yet France is in many ways exceptionally well-positioned for the 21st century. As president, Hollande can use his “bully pulpit” to carry that message to the French, and help the French carry it to the world.

France holds a leadership position in key 21st century industries. No other country derives so much electricity from nuclear energy nor reprocesses nearly all its spent fuel with a spotless safety record. France’s nuclear companies, Areva and EdF, though they operate worldwide, failed to communicate this message, especially after the Fukushima disaster, which resulted in cutbacks in the nuclear industries of several countries — and an anti-nuclear deal by Hollande with the Green party which he has since worked to unravel. Today, however, he pays tribute to Marie Curie, the discoverer of radioactivity and thus of nuclear power.

France’s Veolia Environnement and Suez Environnement are the biggest water treatment and waste management companies on the planet. France itself has one of the most sophisticated water-management systems in the world. The French long-term concession model means that French companies use 21st century technology to manage water and waste across the globe, from London to Alexandria to Manila and Melbourne.

Because of the quality of French education, especially in engineering, the French are world leaders in infrastructure, high-speed rail, and large engineering projects. France itself is a smart logistics platform. There are leading French multinational companies in every global industry. French entrepreneurship in cleantech and biotech is well established. More than a million French citizens live abroad, many of them working in high-tech industries in Silicon Valley, the UK, or Asia.

French culture still speaks to the world, even silently in cinema — witness the success (and Oscars) of The Artist. France remains the world’s number one tourist destination.

France, alongside the US, is thus one of the only complete countries in the world, with independent global reach and renown in diplomacy, defense, industry, agriculture, education, and culture — and the capacity to lead in each of those fields.

Charles de Gaulle said that “France is not France without greatness.” Sarkozy did a masterful job in deploying the greatness of France in international affairs during his term as president. An equally if not more worthy five-year plan for Hollande would be to add to those achievements the full engagement of the French nation with globalization, to convince French society of the need to celebrate France’s centers of excellence, and to inspire the French people to convey that greatness with confidence to the world.

Nicholas Dungan is a senior fellow in the Transatlantic Relations Program at the Atlantic Council. He can be contacted on ndungan@acus.org.

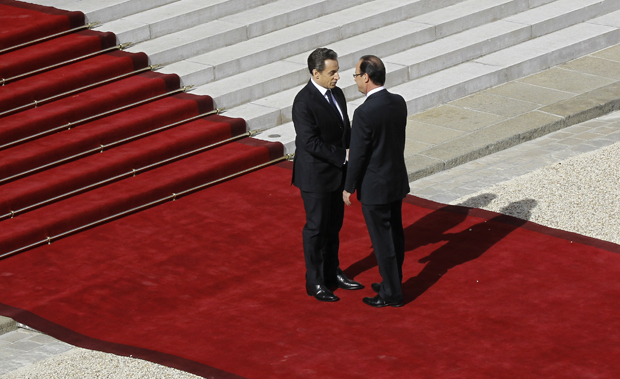

Image: li-hollande-sworn-in-620-02.jpg