Beijing’s decision to fly a reconnaissance balloon over the United States on the eve of Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to China was a serious error that probably stemmed from both operational miscalculations and bureaucratic shortfalls. Assessments of Beijing’s decisionmaking must be tentative because its internal processes are opaque, but the composition of China’s national security apparatus highlights factors that probably contributed to the misjudgment. These factors suggest that operational planners assumed the United States would not identify the balloon as a Chinese platform and did not intentionally time its approach to coincide with Blinken’s trip.

False confidence in ballooning undetected

US officials have connected the balloon to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), calling it “a high-altitude balloon program for intelligence collection.” Only the PLA has the interest, mandate, and capability to acquire and operate a large-scale, long-range reconnaissance platform intended to enter foreign airspace and “monitor sensitive military sites,” as US officials said was its mission. The Chinese Foreign Ministry’s flurry of counteraccusations and claims that multiple civilian research platforms were simultaneously blown off course over the United States and South America lack credibility and suggest an effort to distract attention.

PLA planners misjudged the risk that the United States would track the balloon, but they had reason for false confidence. According to US military officials, the United States failed to detect at least three approaches by these platforms in the past several years. Furthermore, planners may have felt confident that even if the US government were to identify the balloon as a foreign platform, it would be unable to attribute it to China. The PLA would have noted the lack of any protest following previous undetected approaches, and a congressionally mandated intelligence assessment of unidentified aerial phenomena in 2021 suggested that the US was in the dark. The assessment stated only that some aerial phenomena “may be technologies deployed by China, Russia, another nation, or a non-governmental entity.”

Lost in bureaucratic stovepipes

PLA officers may also have failed to take Blinken’s visit into consideration because of stovepipes within the Chinese national security system. The visit was part of a carefully choreographed series of exchanges that both Chinese leader Xi Jinping and the Biden administration had worked assiduously to set up, and for the civilian foreign-affairs bureaucracy it was one of the most important events of the year. But the PLA had little direct involvement, partly due to Beijing’s disinterest in strengthening bilateral military channels, and most senior officers were probably only peripherally aware of the preparations. The balloon’s course may also have been decided before the timing of the visit was confirmed and shared with the PLA, and we do not know how much maneuvering capacity the platform has. A Foreign Ministry spokesman implied in mid-January that Blinken’s itinerary was still being ironed out.

Xi’s absolute control over the PLA and insistence on strict obedience rules out any deliberate attempt by the PLA to defy his intentions or sabotage a diplomatic engagement in which he planned to take part. But the incident does reveal limitations in the effectiveness and scope of the Central National Security Commission (NSC), the main mechanism Xi created to synchronize national security across the civilian and military systems. China’s NSC is one of the few bodies that brings together party, state, and military leaders to address national security affairs. Previously published member lists suggest that Blinken’s counterpart Wang Yi and the chief of the PLA’s Joint Staff Department, who should have had general visibility into the balloon program, sit together on the NSC.

Deconflicting military and foreign-policy initiatives is hard in any system, but the inauspicious timing of the balloon overflight is a useful data point that suggests shortcomings in China’s NSC and other coordination mechanisms. Xi’s nebulous definition of national security to encompass social, ideological, and cultural aspects alongside military, diplomatic, and economic factors may detract from the NSC’s ability to focus on coordinating the external aspects of China’s national-security policies.

Why to expect more missteps

One of the most important underlying drivers of poorly timed and uncoordinated PLA activities is the extraordinarily rapid growth in the scope and scale of its operations. Unlike the US military, the PLA’s leaders and staff officers are frequently operating for the first time in new areas of the world, with novel platforms, and in new domains, some of which involve unexpected political ramifications. Some of their most diplomatically damaging missteps have occurred when operating new platforms in new ways: the 2007 anti-satellite missile test that generated hazardous space debris, the 2011 test flight of the J-20 stealth fighter that marred another cabinet-level visit, and the surveillance balloon.

Most senior PLA officers also have had relatively little experience with operations that involve extensive international political or diplomatic considerations. Joel Wuthnow at National Defense University found in 2021 that no four-star PLA officer had been stationed abroad, compared with 58 percent of US four-stars who had served in a foreign country. PLA army officers also continue to occupy the lion’s share of senior positions and they are less likely to have been involved in politically charged interactions with foreign military forces than their navy and air force colleagues. For example, the PLA’s Joint Staff Department is the natural locus for coordinating its operational activities with overall foreign policies, and current chief Liu Zhenli served almost thirty-nine of the prior forty years of his career in domestic army units and the army headquarters.

Beijing’s botched operation has injected a volatile note into bilateral relations at the beginning of a year that is likely to see further strain given the reported plans of US House Speaker Kevin McCarthy to visit Taiwan. But it may also serve as a useful cautionary lesson for Xi and the rest of China’s leadership. The embarrassing exposure may reinforce concerns in Xi’s mind not only about the capabilities of PLA platforms but about his military’s capacity to correctly gauge the risks of high-stakes operations. It may also bolster his appraisal of US intelligence capabilities a year after Chinese officials were reportedly skeptical of US warnings about Russia’s plans to invade Ukraine. With the prospect of more Sino-US confrontations on the horizon, a reminder of the inherent uncertainties of aggressive military actions could be the silver lining on an otherwise destabilizing incident.

Mark Parker Young is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub, a principal analyst at Mandiant, and a former US deputy national intelligence officer for East Asia.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

Further reading

Fri, Feb 3, 2023

Five questions (and expert answers) about the curious case of the Chinese spy balloon

New Atlanticist By

US fighter jets have shot down a suspected Chinese spy balloon, but the tensions linger in the world's most important bilateral relationship. Our experts float their takes.

Fri, Jan 20, 2023

China and the new globalization

Report By Franklin D. Kramer

The unitary globalized economy no longer exists. Driven in significant part by security considerations, a new and more diverse globalization is both required and being built. The transition is ongoing, and its final form is yet to be determined.

Thu, Nov 4, 2021

FAST THINKING: China’s stunning military buildup

Fast Thinking By

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) could field one thousand nuclear warheads by 2030. What should the US do about it?

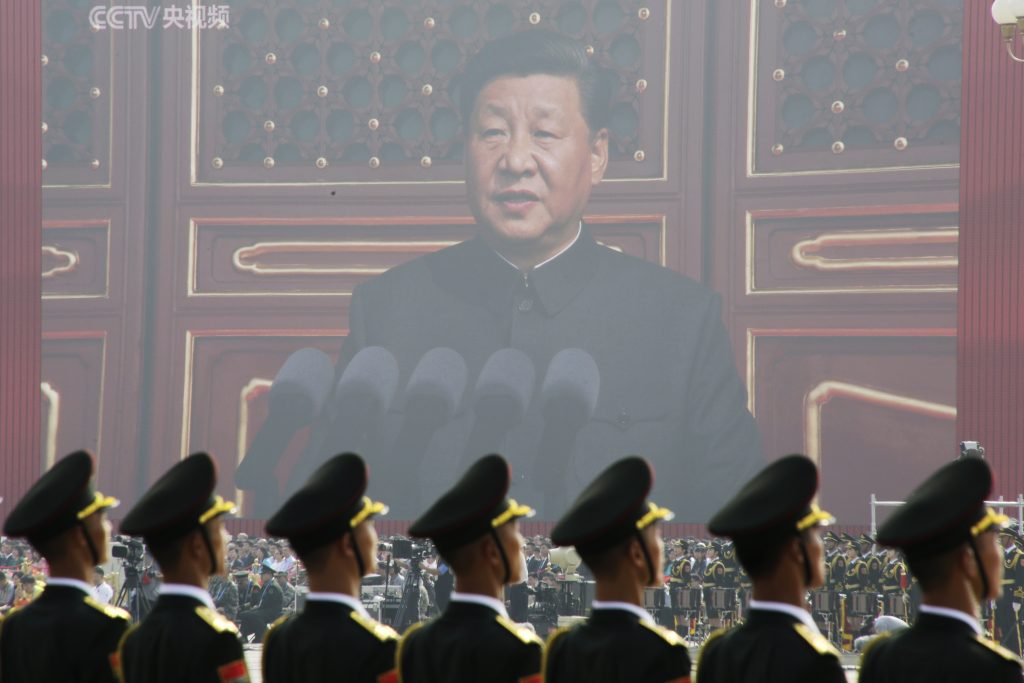

Image: Soldiers of People's Liberation Army (PLA) are seen before a giant screen as Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks at the military parade marking the 70th founding anniversary of People's Republic of China, on its National Day in Beijing, China October 1, 2019. REUTERS/Jason Lee