Delivering justice and jobs is the real test of Ghana’s storied democracy

Bottom lines up front

- Civil society and independent media are the backbone of Ghana’s democracy: Their roles as watchdogs, notably real-time monitoring and publication of polling-station election results, has strengthened credibility of election outcomes.

- Judicial independence remains fragile, with public trust in the judiciary dropping by 20 percentage points since 2011.

- Limited job prospects for Ghana’s growing population of educated youth present a significant threat to its democratic consolidation.

This is the first chapter in the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s 2026 Atlas, which analyzes the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

Evolution of freedom

Ghana’s signature achievement since the mid-1990s is the consolidation of civic and political freedoms and a competitive political order in which citizens, journalists, and civic organizations routinely hold leaders to account. The durability of this achievement is not a result of elite benevolence or political will but the product of a dense, independent civil society and a remarkably resilient independent media ecosystem. When governments test the boundaries of civic space, the response is often swift and organized; this social infrastructure is the primary reason Ghana’s civic and political freedoms have remained consistently strong for more than two decades. This context is reflected in the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Indexes’ political subindex for Ghana, which sits well above the economic and legal subindices. In recent years, it sits in the low-to-mid 70s out of a maximum score of 100, a pattern that aligns with lived realities. In the most recent Afrobarometer survey, conducted in 2024, an overwhelming majority of Ghanaians (85 percent) reported that they did not fear political violence or intimidation during the last national elections, a strong testament to the electoral freedoms that Ghanaians enjoy. Moreover, a majority (52 percent) expressed trust in civil society organizations, ahead of religious leaders (who are trusted by 49 percent). Only the military (trusted by 65 percent) ranks ahead of civil society organizations in Ghana.1Center for Democratic Development, Afrobarometer Round 10 Survey in Ghana, 2024, https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Ghana-summary-of-results-Afrobarometer-R10-22april25.pdf (see pages 30, 32, and 33 of the summary of results tables).

The historical roots of this civic vigilance matter. From the anti-colonial mobilization led by Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first post-independence president, and mass professional and student associations to later generations of advocacy groups and think tanks, Ghanaians have long treated resistance to state overreach as a civic obligation.

As formal unions of lawyers, teachers, students, and medical professionals gave way to contemporary civil society and independent media organizations and research networks—among them, the Media Foundation for West Africa, the Ghana Anti-Corruption Coalition, the Ghana Integrity Initiative, the Ghana Center for Democratic Development, and many others, including subnational advocacy groups—the core impulse has remained the same: to protect and defend civic space, demand procedural fairness, and insist that those in power remain answerable to the public. This explains why the social reaction to efforts to undermine political freedoms is often met with resistance and why Ghana’s political openings have not been easily reversed.

Ghanaians have long treated resistance to state overreach as a civic obligation.

Electoral integrity is a useful illustration of how these social checks operate. While the courts can usually be swayed by partisan crosscurrents when individual political actors are charged with corruption or other acts of impropriety, the dynamic is often different with election disputes. The vigilance of civil society and independent media organizations in monitoring and independently collating election results at the polling-station level often helps to provide credible evidence when electoral disputes arise. The volume and quality of that evidence strengthen adjudication, making it harder for judicial bias to gain traction and increasing the credibility of outcomes, even in contentious contests.2For causal evidence that domestic observers in Ghana’s 2012 elections reduced fraud and violence at monitored stations and altered parties’ manipulation strategies, see Joseph Asunka et al., “Electoral Fraud or Violence: The Effect of Observers on Party Manipulation Strategies,” British Journal of Political Science 49, no. 1 (2019): 129–51. This distinction is important: While the administration of justice in ordinary (nonpolitical) cases is broadly reliable, the politicization of corruption cases can distort judicial behavior; election cases, by contrast, have benefitted from robust, external scrutiny that fortifies the work of the courts.

This juxtaposition points to the core challenge in Ghana’s performance on legal freedom: The judiciary’s structural vulnerability to executive influence, particularly through appointments to the High Court and Supreme Court. Observers can—and do—sort judges into partisan “buckets,” a perception that inevitably erodes confidence in the system’s neutrality. Survey data clearly show a deterioration of citizens’ trust in the judicial system in the last fifteen years, falling by 20 percentage points since 2011.3See the Afrobarometer report on public trust in institutions here: https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/AD891-PAP20-Africans-trust-in-key-institutions-and-leaders-is-weakening-Afrobarometer-31oct24.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Yet outside of high-stakes political cases, the courts tend to function competently and deliver justice with regularity.

Recent movement in the legal subindex has been mildly positive, driven in part by improvements in informality and, to a lesser degree, by steadier security conditions after the turbulence of the early 2000s. On informality, the government’s digitalization initiatives, including the introduction of national (and tax) identification (the Ghana Card) and a digital address system, have helped to identify and increasingly formalize informal businesses. Other initiatives, such as the institution of fee-free secondary education, opened opportunities for young Ghanaians to further their education instead of entering the informal economy. The National Youth Employment Program, although relatively less successful, helped to draw young entrepreneurs into more formalized activities. Finally, a surge of capital investments into construction, alongside an expansion in mining activities, has created demand for artisans, contractors, and allied tradespeople who transact in more formal ways than the street-level microenterprise typical in developing economies. The result is a measurable reduction in the prevalence of informality, a trend visible within the relevant component of the legal subindex.

The gradual strengthening of security owes more to internal stability than to a benign regional environment. Ghana’s northern border with Burkina Faso and proximity to Nigeria’s insurgency-affected areas create constant risks, and yet Ghana has avoided the cascade of instability that has afflicted parts of the Sahel. That relative steadiness, together with the normal functioning of everyday justice for nonpolitical cases, helps explain why legal freedom is trending slightly upward despite persistent concerns about executive sway over judicial appointments and decisions.

Ghana has avoided the cascade of instability that has afflicted parts of the Sahel.

Corruption control within the justice sector is another area to watch. Across administrations, chief justices have consistently placed anti-corruption at the center of their institutional reform agendas, and recent executive appeals to rebuild public trust in the courts suggest continued political salience. However, these public commitments have not always translated into tangible reforms or outcomes. Public perception of judicial corruption remains high: According to the 2024 Afrobarometer survey, more than 40 percent of Ghanaians believe that “most or all judges and magistrates” are corrupt.4Center for Democratic Development, “Ghanaians Decry Widespread Corruption, Afrobarometer Survey Shows,” news release, February 14, 2025, https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/R10-News-release-Ghanaians-decry-widespread-corruption-Afrobarometer-14feb25.pdf. The growing trend of presidents appointing loyalists to the Supreme Court has only reinforced these perceptions, contributing to Ghana’s relatively weak performance on the legal subindex. The ongoing constitutional review presents an opportunity to reform judicial appointments and promotions, tighten avenues for corruption, and strengthen judicial independence.

Ghana’s strong performance on elections, civil liberties, and political rights within the political subindex is tempered by weaker scores on legislative constraints on the executive, highlighting concerns about the effectiveness of institutional checks in practice. However, civil society remains uncompromising in defending democratic norms, including contesting attempts to erode these checks. The resulting equilibrium is not perfect—nor is it immutable—but it has proven remarkably resilient over the past generation.

Economic freedoms have followed their own trajectory, with a notable increase from the mid-2000s into the first half of the 2010s, a period that coincided with the broader “Africa Rising” narrative. This period was characterized by strong improvements in governance and economic growth, rising incomes, and a growing middle class. Consolidation of Ghana’s return to constitutional democracy commenced in the year 2000 with the transfer of power from the ruling party to an opposition party, which further boosted optimism in the country’s political and economic outlook. The new political leadership signaled a clear focus on improving the economy, and market openness and property-rights enforcement seemed to find firmer footing. Former President John Kufuor is remembered in this context for emphasizing macroeconomic health and business-climate improvements that many citizens experienced in their daily lives. The results of committed political leadership and effective economic management are reflected in the economic subindex and the other components such as investment freedom and property rights, starting in the mid-2000s.

The subsequent downturn around 2015 is worth noting. Rising debt-service pressures, coupled with a large budget deficit and high inflation culminated in Ghana going in for an IMF program; a similar pattern occurred around 2023-24 as reflected in the downward trend of the economic subindex. These patterns signal the fragility of gains when fiscal anchors are not backed by disciplined fiscal decisions—such as politically motivated increases in public spending during election years and subsidies on utilities and petroleum products, among others—and when investment freedom and property-rights expectations face credibility questions. These observations underscore that Ghana’s enviable political freedoms do not automatically translate into disciplined fiscal management or sustained economic openness. The freedom metrics capture this: The political subindex remains high, while the economic and legal dimensions fluctuate with policy choices that either reinforce or erode market institutions and democratic norms.

Trade freedom tells a more erratic story. Ghana’s trade policy framework has generally been open by regional standards, but the component’s volatility reflects the broader health of the economy and investors’ read on the policy environment. In periods of economic stress, policy consistency suffers, and openness on paper does not translate into confidence in practice. The trends in the data thus track not only tariff schedules and non-tariff measures but also the credibility of macroeconomic management, which is often punctuated in election years.

The trajectory of women’s economic freedom stands out as a major structural improvement. Around 2004, there was a steep rise in the economic subindex driven in part by a cluster of women’s empowerment policies of the Kufuor administration: free maternal health services, including postnatal care services that reduced a key barrier to women’s labor-market participation, and explicit efforts to expand women’s access to finance and enterprise support. Those initiatives may have helped to boost women’s economic autonomy and anchor a higher plateau that persisted in the years that followed. The component’s level has stagnated since about 2008 and hence leaves some room for improvement—but the rapid change around 2004 is unmistakable. Recent Afrobarometer survey data for Ghana show strong popular support for women to have equal rights to work as men. However, more than a quarter of Ghanaians (26 percent) identify employers’ preference for hiring men as the top barrier to women’s advancement, ahead of childcare (17 percent) and skills gaps (16 percent).5Ghana Round 10 Summary of Results, April 22, 2025, https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Ghana-summary-of-results-Afrobarometer-R10-22april25.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Where do remaining constraints lie? First, land ownership: In Ghana, community and family lands are predominantly controlled by male heads; women’s ownership and collateralization of land remain very limited. Given the economic value of land, women remain at a significant disadvantage that dampens entrepreneurship, constrains access to credit, and restricts intergenerational wealth transfer for women. Second, intrahousehold decision-making: In many households, women’s ability to take paid work outside the home remains mediated by male authority. These social and legal frictions are the kinds of de facto constraints that keep the Women’s Economic Freedom component below its potential despite the formal policy gains that started in the mid-2000s.

Evolution of prosperity

Ghana’s prosperity trajectory since the mid-2000s mirrors, in broad outline, the “Africa Rising” era: a period of macroeconomic optimism, improved governance, favorable terms of trade, and political stability across much of the continent. Between 2005 and the mid-2010s, the Prosperity Index registered a strong and upward trend, reflecting the robust growth in incomes and steady improvements in social indicators, even as inequality widened in the classic early-development pattern. Ghana rode this wave and, for several years, significantly outpaced the sub-Saharan Africa average.

The story of the income component is familiar but still striking in its local particulars. A large discovery of offshore oil in the late 2000s added a new driver to a commodity basket already weighted toward gold and cocoa. In the mid-2000s, when global commodity prices were favorable, Ghana’s growth accelerated sharply; in 2011, Ghana recorded a double-digit real GDP growth rate (about 11 percent), up from about 8 percent the year prior. Oil windfalls amplified these gains, though they also heightened exposure to volatility and raised questions about how resource-linked revenues were managed.6According to an Afrobarometer survey in 2022, 85 percent of Ghanaians support tighter regulations of natural resource extraction. See Center for Democratic Development, “Ghanaians Call for Tighter Regulation of Natural Resource Extraction,” news release, November 8, 2022, https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/R9-News-release-Ghanaians-call-for-tighter-regulation-of-natural-resource-extraction-Afrobarometer-bh-7november22.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com. The income component of the Prosperity Index captures this rise and the subsequent plateau, which has persisted over the last decade. Reversals are visible too, mainly coinciding with the two IMF interventions mentioned earlier, driven in large part by fiscal indiscipline during election years.

The inequality component of the Prosperity Index shows a rapid deterioration, especially from the year 2000. But the composition of Ghana’s inequality is complex. It is not simply a rural-urban story; it is also generational. Large cohorts of better-educated youth, especially those under thirty-five, struggle to find formal employment at scale, while older cohorts, who are relatively less educated, hold on to existing jobs.7Josephine Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny, Shannon van Wyk-Khosa, and Joseph Asunka, “Africa’s Youth: More Educated, Less Employed, Still Unheard in Policy and Development,” Afrobarometer, November 15, 2023, https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AD734-PAP3-Africas-youth-More-educated-less-employed-still-unheard-Afrobarometer-13nov23.pdf. The consequence is an age-skewed labor market that expands inequality even as education levels rise. On the rural side, extensive reliance on small-holder agriculture—more than 40 percent of the population is engaged in subsistence farming—keeps cash incomes low. Climate variability has compounded these pressures, with shifts in rainfall and temperature patterns outpacing the seed and crop research needed to adapt. The Index’s inequality line captures the macro pattern, and the underlying micro-mechanisms are the youth (un)employment crunch and the persistent productivity trap of smallholder agriculture.

Environment and health are relative bright spots. The national push to switch households from charcoal and wood to liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) for cooking—especially the 2013 rural LGP promotion program—may have helped to reduce indoor air pollution and, with it, the number of respiratory and related illnesses. Additionally, the government’s 2021 Green Ghana initiative to plant five million trees nationwide to combat desertification signaled a strong commitment to environmental issues in the country.8Elorm Ntumy, “Green Ghana Day: A Chance to Turn the Tide on Deforestation,” UN Capital Development Fund, 2021, https://www.uncdf.org/article/6857/green-ghana-day. The behavioral transition and practical action on desertification probably account for the Prosperity Index’s environment component alongside CO₂ and other measures. On the health side, Ghana’s COVID-19 response benefitted from institutional memory and capacity developed during earlier West African epidemics. Ebola never crossed into Ghana, thanks in part to the region’s experience dealing with health epidemics. When COVID-19 broke out, pandemic protocols were quickly activated and enforced, which resulted in comparatively low infection rates and deaths and a health system that proved more resilient than many expected.

Education presents a more mixed picture. Policy volatility in the secondary cycle—oscillating between three- and four-year models—created confusion and capacity mismatches just as youth cohorts ballooned. Free, compulsory basic education expanded access, but in many districts infrastructure and staffing could not keep pace, producing “shift systems” and, in some cases, causing students to drop out before completing upper-secondary education. Because the Prosperity Index’s education component bundles mean years of schooling with expected attainment, the friction from policy oscillation and demographic pressure is visible at a level that remains middling despite long-run improvements.

Finally, informality also intersects with prosperity through the labor market. The government’s digitalization programs—the introduction of the Ghana Card, which links to individual tax identification numbers, as well as the digital address system—have expanded formalization of the national economy. Moreover, governments’ special initiatives to increase youth employment and a boon in the construction and mining sectors have pulled workers into the formal sector. These interventions should, in principle, raise tax revenues and improve public service availability and access over time. The hard question is durability: Formalization built on cyclical or enclave sectors may not last if investment slows or governance costs mount. The Prosperity Index cannot answer that question by itself, but its pattern—modest gains in prosperity with uneven distributional effects and vulnerability to macro slippage—point to areas where reforms might matter most.

The path forward

The economic, social, and political outlook of Ghana’s next decade will depend largely on the steadiness with which it improves core institutions and transforms its civic strength into predictable, broad-based gains. Moreover, aligning reforms to citizens’ stated priorities—jobs, public services, and integrity—can increase traction.9See Joseph Asunka and E. Gyimah-Boadi, “People-Centered Development: Why the Policy Priorities and Lived Experiences of African Citizens Should Matter for National Development Policy,” Foresight Africa 2025–2030, May 13, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/people-centered-development-why-the-policy-priorities-and-lived-experiences-of-african-citizens-should-matter-for-national-development-policy/. The political foundations are relatively strong; the next important step is ensuring that the transparency and accountability mechanisms that guard the conduct of elections also insulate the justice system from partisan distortion in high-stakes cases. Judicial appointments will remain politically salient, but the deeper imperative is to tighten the system’s incentives so that corruption cases are decided on evidence rather than allegiance. Civil society and media can help—by maintaining the evidentiary standard that has worked in election disputes—but ultimately the judiciary must build a reputation for political impartiality that is strong enough to withstand executive pressure. The ongoing constitutional review offers a chance to implement a judicial reform agenda that delivers on this objective.

Economic management is the second pillar. The political business cycles are familiar by now: A new government comes to power and starts out with prudent fiscal management that boosts confidence and attracts investment, often resulting in an increase in the economic subindex. Then comes election time and fiscal indiscipline—such as excessive borrowing and indiscriminate public spending with weak fiscal oversight—erode confidence and investment freedom, triggering adjustment and decline. Breaking this cycle requires more than fiscal rules on paper; it requires political commitment to enforce them consistently and minimize politically motivated borrowing and spending. The 2015 and 2024 IMF programs are markers of what happens when that discipline falters. In the coming years, the goal should be to make investment freedom boring—i.e., stable, predictable, and insulated from the electoral business cycle.

On economic freedom, two structural agendas stand out. The first is women’s economic freedom. The 2004 leap tied to women-centered policies shows how targeted policy can permanently raise the ceiling of economic progress. The unfinished business is in property rights, especially land ownership. In areas where family land remains the norm and titles are controlled by male heads, women’s ability to own, mortgage, and leverage land is curtailed. Reform here is politically delicate, embedded in social norms and local authority structures, but the economic payoff could be enormous: more women-owned firms, better access to credit, and fairer intergenerational asset accumulation. The women’s freedom component of the Index offers a clear benchmark; moving from the mid-seventies to the high eighties would require not just programs but enforceable property rights.

The second is youth (un)employment. Inequality in Ghana increasingly wears a generational face;a cohort of better-educated young people cannot find formal, stable jobs in sufficient numbers. Policy tools here must focus on easing business entry, expansion in labor-absorbing sectors, and modernizing agricultural value chains so that rural youth are not confined to subsistence farming. Climate-smart research and extension services, reliable input markets, and storage and transport infrastructure can help farmers move up the value ladder—and should be paired with vocational pathways aligned to construction, light manufacturing, and services. Such an agenda could help to address the twin problems of rural low productivity and urban underemployment.

Strengthened legal freedom and rule of law can support both agendas if reforms focus on clarity of the law and the quality of bureaucracy. Where statutes are clear, predictable, and enforced uniformly, the transaction costs that push firms into informality will fall; where frontline administration is competent and corruption risks are contained, formalization becomes a benefit rather than a burden. Ghana’s recent sector-led formalization has demonstrated that workers and firms will choose formal channels when the opportunity set changes. The task now is to make those choices systemic: digital one-stop services for business registration and tax collection; credible and quick adjudication for commercial disputes; and incentives for small firms to formalize without fear of retroactive penalties.

Regional (in)security will remain a concerning external variable. Instability in parts of the Sahel and the enduring threat of violent extremism in neighboring regions create risks that Ghana has to grapple with. The country’s success to date reflects internal discipline and professional security services, but the calculus can change quickly as alliances and external funding priorities shift. Ghana’s democratic resilience—anchored in a vigilant civil society and robust private media—makes it better placed than many to navigate these shocks without sacrificing core freedoms. The imperative is to ensure that security responses remain proportionate and bounded by law, so that security gains are not purchased at the cost of civil and political liberties that have been the bedrock of Ghana’s democratic success story.

Geoeconomic partnerships will also shape the opportunity set for Ghana. Specifically, infrastructure that lowers freight costs—an inland port located up north with rail connectivity, for instance—has immediate appeal, and Ghana would do well by investing in this area. Engagements with Chinese state and private investors are often judged domestically on whether they deliver such tangible benefits; they are not, by themselves, read as threats to democratic credentials. The test for the next decade is to structure these partnerships transparently, align them with national priorities, and avoid governance concessions that have complicated infrastructure deals elsewhere. If done well, they can help stabilize economic policy by supporting trade freedom in practice, not just on paper, and by attracting private investment that widens formal employment.

The prosperity side of the ledger will hinge on two slow-moving but decisive social investments. The first is education system reliability. When secondary school terms oscillate, cohort planning collapses; when seating capacity lags enrollment, “shift systems” lead to lost learning and early exits. The policy objective must prioritize stability: a curriculum and cycle length that survives political alternation, infrastructure that grows with cohorts, and targeted support to keep marginal students—especially rural girls—through upper secondary. If achieved, educational attainment will move steadily upward, with compounding effects on income and inequality.

The second is health and environment. Ghana’s clean cooking fuel and afforestation initiatives demonstrate how coordinated public messaging and practical access can drive large-scale shifts in household behavior—which often yield immediate and tangible benefits. Extending this logic—through cleaner fuels, safer urban air, adaptive health systems, and expanded green coverage—can enhance environmental quality, improve health outcomes, and free up resources otherwise consumed by preventable disease burdens.

Finally, the country’s political economy will continue to be shaped by how it manages its natural resource wealth. When mineral and oil revenues supplant tax collection, citizens have fewer reasons to monitor spending, governments face fewer incentives to be transparent, public resource leakages rise, and the discipline that keeps debt manageable erodes. A forward-looking reform would therefore tackle the credible fiscal rules that bind during booms, transparent revenue management that makes it costly to divert funds, and a tax system that is simple enough to comply with and fair enough to legitimize. The expanded government digitalization programs offer sound foundations to make this possible. If Ghana can lock in these basics while preserving the civic and media freedoms that have distinguished it for three decades, legal and economic institutions will catch up and converge with political freedom, and prosperity gains will follow.

Ghana’s comparative advantage is … the lived practice of accountability that precedes and outlasts any single administration.

Civil society and media have proven that they can guard the franchise; the task before us is to extend that guardianship to the legal system’s most politically sensitive corners and to the fiscal choices that unlock prosperity and avoid the familiar cycle of fiscal indiscipline, crisis, and repair. If managed well, the evidence should be visible where it matters most: a steadier investment freedom line, a women’s economic freedom score that rises again rather than plateaus, an inequality curve that bends as youth employment expands, and a legal freedom profile that reflects not just order in the streets but fairness in the courtroom. That is the trajectory Ghana can reasonably aim for in the decade ahead, and it is within reach.

about the author

Joseph Asunka is the CEO of Afrobarometer, a pan-African survey research organization that conducts public attitude surveys on governance and social issues across the continent. His research interests are in governance, democracy, and political economy of development. He holds a PhD in political science from the University of California at Los Angeles.

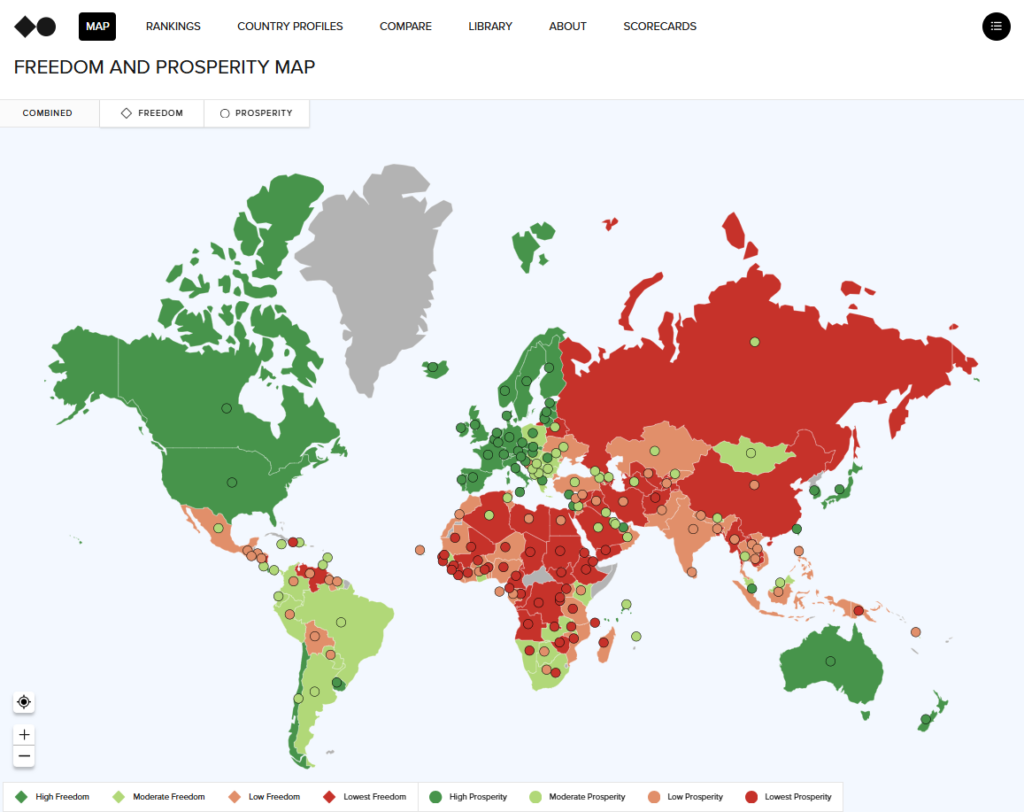

Explore the data

The Indexes rank 164 countries around the world. Use our site to explore thirty years of data, compare countries and regions, and examine the subindexes and indicators that comprise our Indexes.

Stay Updated

Get the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s latest reports, research, and events.

Stay connected

Read all editions

2026 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Against a global backdrop of uncertainty, fragmentation, and shifting priorities, we invited leading economists and scholars to dive deep into the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries around the world. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

2025 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists, scholars, and diplomats analyze the state of freedom and prosperity in eighteen countries around the world, looking back not only on a consequential year but across twenty-nine years of data on markets, rights, and the rule of law.

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Image: A woman votes during the presidential and parliamentary election at a polling station in Bole, Ghana, December 7, 2024. REUTERS/Francis Kokoroko

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media