How a new global defense bank—the ‘Defense, Security, and Resilience Bank’—can solve US and allied funding problems

Key points

- NATO’s recurring funding problems could be solved with a new, internationally governed financial institution: the Defense, Security, and Resilience Bank.

- By underwriting risks for commercial banks, the bank would enable nations to boost defense production, ensuring supply chains are equipped to meet modern security demands.

- With collective backing from allies, the bank could drive innovation, enhance resilience, and be operational as soon as 2027.

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- A blueprint for the new bank

- Faster decisions, better borrowing terms

- Political will remains the key challenge

- How the bank would function

- What the bank would do

- Conclusion

- Appendix

Executive summary

The underinvestment in defense, security and resilience by a significant number of allied nations, falling short of the minimum 2 percent gross domestic product (GDP) NATO target, or who are simply unable to finance credible defense capabilities,1Of NATO’s thirty-two members eleven currently meet the 2 percent target. The current gap in defense spending among members to simply reach the minimum of 2 percent is estimated as approximately $80 billion. creates political disunity and practical limitations in meeting collective defense treaty commitments.2Max Bergmann and Benjamin Haddad, “The EU should borrow together once again – this time for common defense,” Politico, March 4, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-war-russia-europe-defense-borrow-together-military-spending/. This issue largely stems from political rather than economic factors. Despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and rising geopolitical tensions with China, the public in many European nations and Canada prioritize spending on healthcare, education, and public infrastructure over defense.3Janan Ganesh, “Western voters won’t give up the peace dividend,” Financial Times, March 28, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/88b78ab0-2017-4b6f-87f0-a9cf0f491414. This report posits that expecting a drastic shift in these domestic spending priorities remains unlikely.4Jean-Pierre Maulny, “The Impact of the War in Ukraine on the European Defense Market,” Institute for Strategic International Relations, September 1, 2023, https://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/19_ProgEuropeIndusDef_JPMaulny.pdf Instead, a viable solution to this challenge is proposed through the establishment of a Defense, Security and Resilience multilateral lending institution (MLI): what this report is calling the Defense, Security and Resilience bank.

This proposal is grounded in over five years of research and analysis within the NATO International Staff and, externally, in academia, and is complemented by insights from JP Morgan’s supranational (MLI) finance team. It incorporates perspectives from extensive dialogues, solicited by the author, with allied representatives across most Euro-Atlantic governments including ministries of defense, finance, and foreign affairs. The concept of a Defense, Security and Resilience bank— originally called the NATO bank initially briefed to NATO’s secretary general’s office in 2019,5Robert Murray, “A NATO bank is the best way to fund defense in a more dangerous world,” Financial Times, April 20, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/18e62451-d066-497e-93dd-f42decd59410 and presented in a 2020 Atlantic Council paper6Max Bergmann and Siena Cicarelli, “Open a bank,” Atlantic Council, October 14, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/content-series/nato20-2020/open-a-bank/ and a 2023 Financial Times op-ed7Robert Murray, “A NATO Bank is the best way to fund defense in a more dangerous world,” Financial Times, April 20, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/18e62451-d066-497e-93dd-f42decd59410—is explored in depth in this report, including the anticipated operational dynamics and the advantages and challenges for allies in creating it.

Since that 2019 NATO briefing, the geopolitical landscape has evolved significantly. The emergence of new challenges, notably the war in Ukraine and a shift in global economic conditions (higher domestic interest rates, and exposure to inflation), underscore the relevance of the proposed bank to support long-term, stable defense planning. Unlike existing MLIs, none of which are mandated or equipped to address allies’ unique defense and security financing needs, the Defense, Security and Resilience bank would fill a crucial gap.8Johannes F. Linn, “Expand multilateral development bank financing, but do it the right way,” Brookings, November 29, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/11/29/expand-multilateral-development-bank-financing-but-do-it-the-right-way/;Jakob Hanke Vela, “Poland’s border problems escalate,” Politico, September 26, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/newsletter/brussels-playbook/polands-border-problems-escalate/ For allies across both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions, the bank could go beyond offering low-interest loans for defense modernization to facilitating equipment leasing, currency hedging, and supporting critical infrastructure and rebuilding efforts in conflict zones like Ukraine. Its counter-cyclical capacity would serve as a financial safety net for all allies, preserving defense spending stability and collective security during economic downturns—i.e. enhancing international resilience.

An additional critical function of the DSR bank would be to underwrite the risk for commercial banks, enabling them to extend financing to defense companies across the supply chain. This mechanism is essential to sustaining and expanding production capacity, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that are pivotal to defense manufacturing but often struggle to access capital. By guaranteeing a portion of the risk, the DSR bank would ensure that these companies can secure the financing needed to maintain operations, fulfill contracts, and invest in scaling their capabilities. This approach not only stabilizes supply chains but also reinforces the defense industrial base, ensuring production readiness and resilience during times of heightened demand or economic uncertainty.

Securing a AAA credit rating would be paramount for the bank to effectively fulfill its potential, enabling it to provide low-cost loans and enhancing defense-spending feasibility for the bank’s member nations. This rating would be attainable even though many Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allied nations do not individually possess a AAA rating, which is the best among investment-grade bonds (see the appendix).9The only NATO members that currently hold a AAA rating are: Canada, Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. While respecting the sovereignty of its member nations, the bank’s operations must need to navigate the inherently political nature of establishing a defense, security and resilience-focused MLI. It is proposed that a small group of nations act as anchor nations for this efforts.10 Ed Arnold, Robbie Boyd, Rob Murray, and Lord Stuart Peach, “A Joint Expeditionary Force Fund: A Better Way to Finance Defense?” RUSI, October 27, 2023, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/joint-expeditionary-force-fund-better-way-finance-defense

To effectively capitalize the proposed bank, allies would be invited to provide paid-in capital, a standard approach for multilateral lending institutions (MLIs). Additionally, a politically sensitive yet innovative proposal could involve using seized Russian central bank funds—or at least the interest generated from these funds—currently held in Belgium and managed by Euroclear. Leveraging these funds could provide a robust financial foundation for the bank, allowing allied nations to establish a Defense, Security, and Resilience bank with Russian assets as paid-in capital. By channeling Russian central bank resources, the bank could finance loans used to procure armaments for Ukraine, enabling them to sustain their defense efforts. However, given the potential for significant political and diplomatic repercussions, including possible retaliatory actions by Russia, this approach demands careful consideration and consensus among the bank’s prospective shareholder nations.

Effective governance and compliance with established financial regulations would be essential for the bank’s successful operation. The formation of a board of directors, consisting of experts from member nations, would be pivotal for ensuring strategic alignment and sound decision-making. The proposed design for the bank, as a regulated entity, is geared to operation with the efficiency characteristic of MLIs, with which all allies and partners are familiar and members of.

The Defense, Security and Resilience bank is proposed as a strategic tool to address the challenges of defense spending among Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific nations. It offers a complementary financing mechanism, particularly beneficial for nations grappling with high debt-to-GDP ratios or elevated borrowing costs. While not a panacea, such a bank could ease fiscal pressures and encourage increased defense, security and resilience investment across member state regions. Indeed, in the context of defense it should be noted that it is not too much debt that risks being a burden on future generations it is too little investment.

The establishment of the Defense, Security, and Resilience (DSR) bank depends in-part on founding members with strong credit ratings to underpin its financial stability and operations. While the ultimate goal is to allow membership from all Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allies, the bank will initially require a core group of anchor nations to build its balance sheet and governance structure. The Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF)—a coalition of ten allied nations with robust credit ratings—along with the United States and Japan, could form this foundational group.11Lord Stuart Peach, Robbie Boyd, and Ed Arnold, “Stretching the Joint Expeditionary Force: An Idea for Our Times,” RUSI, September 8, 2023, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/stretching-joint-expeditionary-force-idea-our-times; The JEF is comprised of the United Kingdom, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. The appendix provides a breakdown of NATO allies and their current sovereign credit ratings. This JEF-led approach would establish a credible foundation and could potentially feed into the European Investment Bank (EIB) framework noting that the Defense, Security and Resilience Bank must be created as a separate legal entity with its own credit rating to ensure independent governance and operational flexibility. Once the bank’s charter is in place by those anchor nations, remaining NATO, EU, and Indo-Pacific allies and partners would be invited to join as shareholders, creating an inclusive and resilient institution for defense, security, and resilience financing.

Based on the creation of other MLI constructs, the bank could be operational by 2027.

A blueprint for the new bank

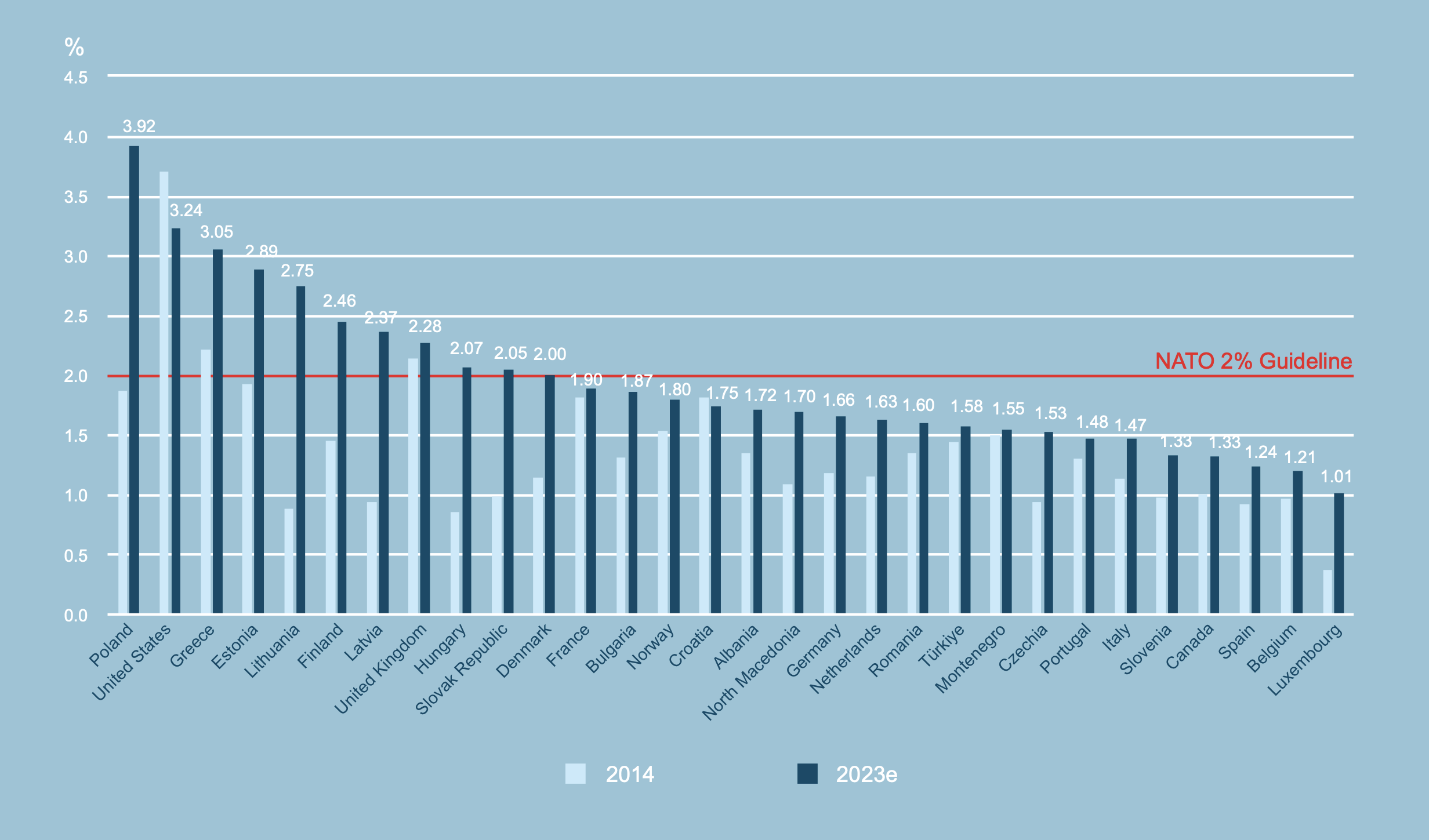

As geopolitical tensions mount, the lens of global scrutiny remains firmly fixed on allied nations and their defense capabilities. Yet despite these escalating pressures, eleven out of thirty-two NATO met the agreed-upon minimum defense spending target of 2 percent12The 2 percent target was reconfirmed by NATO heads of state and government at the 2014 NATO summit in Wales, United Kingdom; NATO, “Wales Summit Declaration,” September 5, 2014, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_112964.htm; Lili Bayer, “Only One-third of NATO Allies Set to Reach Spending Target, New Data Shows,” Politico,July 7, 2023, and https://www.politico.eu/article/only-11-nato-allies-set-to-reach-spending-target-new-data-shows/; and The Secretary General’s Annual Report: 2023, NATO,https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2024/3/pdf/sgar23-en.pdf. of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2023, with an expectation that this figure will rise to twenty three out of thirty-two by the end of 2024.13Includes Sweden, which formally became a NATO member on March 7, 2024. This is positive, but the uncertainty about whether such investment will hold or beholden to annual budget cycles and exogenous shocks continues to hang over both finance and defense ministries alike. Although the validity of the 2 percent target is debatable,14Kathleen McInnis, Daniel Fata, Benjamin Jensen, and Jose Macias, “Pulling their Weight: The Data on NATO Responsibility Sharing,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, February 2024, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2024-02/240222_McInnis_Nato_Responsibility.pdf?VersionId=Lbjn1X8kSdCn0h.mdHQh02hzyiNf9gBL these public commitments by heads of state and government are critical to the Alliance’s capacity to project and sustain military power. The inability of many nations to meet this baseline, while balancing competing domestic expenditures, not only undermines allies’ credibility but also dilutes the deterrent effect it can project onto the world stage.

Figure 1. NATO defense expenditure as a percentage of GDP in 2014 and 2023e (estimated)

In 2024, NATO’s combined defense expenditure neared an all-time high of $1.47 trillion.15NATO “The Secretary General’s Annual Report,” NATO, February 2023, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2024/3/pdf/sgar23-en.pdf OECD,“Annual GDP and components – expenditure approach,” OECD, 2023, https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?lc=en&fs[0]=Topic%2C1%7CEconomy%23ECO%23%7CNational%20accounts%23ECO_NAD%23&fs[1]=Topic%2C2%7CEconomy%23ECO%23%7CNational%20accounts%23ECO_NAD%23%7CGDP%20and%20non-financial%20accounts%23ECO_NAD_GNF%23&pg=0&fc=Topic&snb=53&vw=tb&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_NAMAIN10%40DF_TABLE1_EXPENDITURE_VPVOB&df[ag]=OECD.SDD.NAD&df[vs]=1.0&pd=2023%2C2023&dq=A.AUS%2BAUT%2BBEL%2BCAN%2BCHL%2BCOL%2BCRI%2BCZE%2BDNK%2BEST%2BFIN%2BFRA%2BDEU%2BGRC%2BHUN%2BISL%2BIRL%2BISR%2BITA%2BJPN%2BKOR%2BLVA%2BLTU%2BLUX%2BMEX%2BNLD%2BNZL%2BNOR%2BPOL%2BPRT%2BSVK%2BSVN%2BESP%2BSWE%2BCHE%2BTUR%2BGBR%2BUSA…B1GQ…….&ly[rw]=REF_AREA&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false However, this figure masks a sobering reality. Once adjustments are made for global purchasing power parity, it becomes clear that real-term spending levels have merely returned to those seen two decades ago. This stagnation is particularly alarming given the rapid increase in spending by potential adversaries, with NATO losing ground to both Russia and China in terms of relative expenditure (see figure 2). To put that into context, before the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, a 155-millimeter artillery shell cost a NATO nation around $2,000, but today it is closer to $8,000.16According to Admiral Rob Bauer, NATO’s Chair of the Military Committee speaking at the 2023 NATO Industry Forum in Stockholm.

Figure 2. Military spending at purchasing power parity

Notwithstanding purchasing power parity, the challenge of meeting the 2 percent GDP commitment represents a current deficit of approximately $45 billion.17See the appendix for a comprehensive overview. Additionally, many Central and Eastern European nations still grapple with the legacy of the Cold War, reliant on aging Soviet-era equipment to defend themselves. Modernizing these systems (including jets, armored vehicles, and transport aircraft) necessitates a significant investment, running into hundreds of billions of dollars and euros. Moreover, a plethora of other defense and security-related challenges looms, ranging from infrastructure protection and multinational operation support to Ukraine reconstruction assistance as well as currency cost hedging to support allies acquiring armaments invoiced in nondomestic currencies. Taken together, these challenges demand an outlay estimated to be between $535 billion and $845 billion (see table 1).

Table 1: Overview of proposed areas of operation for the bank

Sources:

- Jean-Pierre Maulny, “The Impact of the War in Ukraine on the European Defense Market,” Institute for Strategic International Relations, September 1, 2023, https://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/19_ProgEuropeIndusDef_JPMaulny.pdf

- NATO Staff Defense Investment financial assessment for 2018–2022.

- Kathleen McInnis, Daniel Fata, Benjamin Jensen, and Jose Macias, “Pulling their Weight: The Data on NATO Responsibility Sharing,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, February 2024, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2024-02/240222_McInnis_Nato_Responsibility.pdf?VersionId=Lbjn1X8kSdCn0h.mdHQh02hzyiNf9gBL

- Pieter-Jan Vandoren, “European Critical Infrastructure,” Trans-European Policy Studies Association, May, 16, 2023, https://tepsa.eu/analysis/european-critical-infrastructure/

- Alice Lipowicz, “EU to spend far less for infrastructure protection,” Washington Technology, July 5, 2005, https://washingtontechnology.com/2005/07/eu-to-spend-far-less-for-infrastructure-protection/328391/

- Bernhard Hammerli and Andrea Renda, “Protecting Critical Infrastructure in the EU,” CEPS Task Force, https://aei.pitt.edu/15445/1/Critical_Infrastructure_Protection_Final_A4.pdf

- BBC, “Afghanistan: What has the conflict cost the US and its allies?” BBC, September 3, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-47391821

- World bank, “Ukraine Recovery and Reconstruction Needs Estimated $349 Billion,” World bank, September 9, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/09/09/ukraine-recovery-and-reconstruction-needs-estimated-349-billion;

- Henry Foy, “NATO plans $100 billion ‘Trump-proof’ fund for Ukraine,” The Financial Times, April 2, 2024 https://www.ft.com/content/254c3b86-2cb9-4c71-824b-dacacbbc9871

- Diana Dimitrova, Mike Lyons, et al., “The Growing Climate Stakes for the Defense Industry,” BCG, September 10, 2021, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/growing-climate-stakes-for-the-defense-industry

Faster decisions, better borrowing terms

With allies facing with formidable and ever-growing fiscal challenges, a bold solution is needed, and the establishment of a Defense, Security and Resilience bank meets that description. This report explores the bank concept, an initiative designed to support allies across both the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions facing fiscal constraints in meeting their defense spending obligations. Acknowledging that financial challenges and political decision-making are at the core of defense investments, the bank should be viewed as a complementary financing option for allies and their sovereign choices. It aims to provide faster decisions and more favorable borrowing terms than available to many nations (table 2), while potentially providing fiscal headroom to all allies, thereby creating more options for domestic tax and spending choices. Considering the diverse economic realities of allied nations, this initiative necessitates a detailed analysis of its implications for nations and their defense, security and resilience obligations.

Through the author’s extensive discussions between 2018 and 2024 with NATO representatives and officials from the majority of members’ respective ministries of defense, foreign affairs, and finance, three key themes emerged regarding the bank: its political, economic, and defense implications. These interactions underline the perceived benefits of the initiative:

Political perspective

- Enhanced political will through collective effort: A DSR bank could foster a renewed commitment to collective defense, thereby creating political momentum and unity. When defense spending is facilitated through a shared institution, it may become more politically acceptable for all governments involved to conduct joint procurement and undertake ambitious projects.18European Union, “President Michel calls for ‘defense bonds’ at EDA Annual Conference 2023,” European Union, November 30, 2023, https://eda.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/2023/11/30/president-michel-calls-for-%27defence-bonds%27-at-eda-annual-conference-2023

- Strategic signaling: Participation as a shareholder in the bank would further demonstrate members’ commitment to the international order, potentially enhancing their influence across various international organizations, while augmenting deterrence through political commitments of fiscal firepower.

- Addressing domestic budget constraints: Politically, borrowing from the bank would offer a strategic way to balance domestic budgetary pressures with international commitments due to extremely low interest rates and potentially very long borrowing timelines, that may not be available domestically to every Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific ally.

Economic perspective

- Lower borrowing costs: The Defense, Security and Resilience bank would offer lower interest rates and faster decisions to many nations, making defense spending through loans more feasible for countries with tight fiscal constraints.

- Budget flexibility: Loans from the bank might allow countries to spread defense spending over longer periods compared to sovereign bonds, offering more economic viability than direct budget allocations. For example, the United Kingdom paid back its World War I war debt in 2015.19BBC, “Government to pay off WW1 debt,” BBC, December 3, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-30306579#

- Economic multiplier effects: Investments in defense can stimulate domestic industries, production and innovation, with the bank serving as a catalyst without the immediate strain of direct spending.

Defense perspective

- Meeting immediate defense needs: The bank could provide timely solutions for countries needing to modernize their defense capabilities.

- Long-term defense planning: Loans could facilitate strategic, long-term defense projects (including stockpiling of key armaments), enhancing predictability and resilience in defense planning as opposed to the annual budgetary cycles many nations endure at present.

- Collective capability enhancement: Financing defense upgrades through the bank could improve the overall capability and readiness of allies wishing to operate together.

However, during the many discussions in the five-year research period, opinions on the bank’s merits varied among allies. Some officials from defense and foreign affairs ministries were initially skeptical about the mechanics of how the bank would work, often due to their unfamiliarity with MLIs. In contrast, finance ministry officials familiar with MLIs showed significantly more openness, focusing on governance rather than fiscal implications. Notably, senior political appointees displayed considerable interest, indicating receptiveness at higher levels of allied political leadership. All of this suggests that the Defense, Security and Resilience bank would interact with various governmental ministries, thus creating challenges for civil servants as they attempt to forge a unified governmental stance, but that the politics of the initiative represent a unique opportunity.

Additional benefits

With strong political support, the bank could be established within eighteen to twenty-four months once a charter is in place.20This estimate is based on input from former senior MLI employees, in conversation with the author, May 24, 2023. All Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allied nations are shareholders in at least one existing MLI and could adapt these structures to suit the bank’s mandate. Furthermore, the bank’s activities could directly stimulate domestic production, drive job creation, and spur technological innovation in member nations. For countries with strong credit ratings, involvement in the bank would offer additional economic benefits and potential increases in tax revenues through greater intra-allied defense sales (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Estimated share of primary NATO member defense export sales (2022)

Political will remains the key challenge

The proposal, however, faces certain hurdles. Some European nations may prefer an exclusive integration of defense financing within existing institutions, specifically the European Investment Bank (EIB), while the United States might view the bank as disproportionately leveraging American credit. Capitalizing the bank would require contributions from its members, and there might be concerns about a borrowing stigma as well as misconceptions about subsidy dynamics.

To address these reservations—particularly those associated to strengthening the EU pillar within NATO—it is imperative that the proposed Defense, Security and Resilience bank framework incorporates mechanisms that explicitly recognize and support the strategic objectives of the European Union in the realm of defense within the transatlantic context of NATO. This includes:

- Ensuring balanced investment: The bank’s investment strategy would need to aim for a balance between supporting allies’ overarching defense objectives and bolstering the EU’s defense capabilities, particularly in areas such as joint procurement, research and development (R&D), and the cultivation of the European defense technology and industrial base (EDTIB). Such an approach would ultimately build resilience within the alliance by reinforcing a more diverse transatlantic defense industrial base.

- Promoting EU defense initiatives: The bank should facilitate and encourage investments in projects that align with key EU defense initiatives, such as the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), the European Defence Fund (EDF), and European Defense Industrial Strategy (EDIS), helping to enhance European strategic autonomy and industrial competitiveness. A stronger and more competitive transatlantic defense market benefits all Euro-Atlantic allies and creates greater levels of geopolitical resilience.

- Adhering to transparency and inclusivity: Decision-making processes within the bank must be transparent and inclusive, allowing for the equitable representation of all shareholder interests. This approach would foster a sense of ownership and commitment among all relevant nations, mitigating fears of undue influence or bias.

- Demonstrating flexibility: The bank should offer flexible financing options that cater to the diverse needs and priorities of all allies, including those with a strong preference for either EU or non-EU-centric defense procurement strategies. This flexibility would ensure that the bank serves as a facilitator of members’ defense objectives rather than a prescriptive entity.

While the DSR Bank offers a promising opportunity to strengthen collective defense capabilities, its implementation must be carefully aligned with the strategic goals and sensitivities of all allies. For the Euro-Atlantic region, this entails creating synergies between NATO and EU defense efforts, while also considering the interests of allied nations in the Indo-Pacific. By bridging these priorities, the bank can contribute to a more resilient and integrated transatlantic defense posture. Nevertheless, the primary challenge will be political: Increasing defense spending ultimately depends on the political will of member nations. Although aligning the varied priorities of allied nations presents complexities, these obstacles are surmountable with careful coordination and commitment.

In summary, the Defense, Security and Resilience bank presents a paradigm shift, offering benefits to all allies across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions and symbolizing a commitment to alliance unity and stability. The remainder of this report will further detail how the bank could operate effectively by merging defense investment with economic incentives for growth, job creation, and enhanced tax revenues.

How the bank would function

The proposed Defense, Security and Resilience bank (with a AAA credit rating) would allow many Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allies to borrow at lower interest rates than their own cost of capital.21See table 2. This financial mechanism would benefit both those countries currently below the 2 percent GDP target and those already meeting it due to the economic activity the bank would bring about in terms of financing defense production. Beyond issuing debt through capital markets, the bank could act as the depository institution for annual monetary commitments from the allies for collective financing of institutions such as NATO. These deposits could be centrally managed and strategically utilized for alliance activities such as capital investment, stockpiling of essential equipment, and R&D projects. This could lead to a more effective, transparent, and dynamic resource allocation process than the current disparate ad-hoc approach nations currently undertake.

As previously highlighted, this report builds on prior work that has made clear arguments for the need of collective allied debt to help pay for future defense.22European Union, “President Michel calls for ‘defense bonds’ at EDA Annual Conference 2023,” European Union, November 30, 2023, https://eda.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/2023/11/30/president-michel-calls-for-%27defence-bonds%27-at-eda-annual-conference-2023; Robert Murray, “A NATO bank is the best way to fund defense in a more dangerous world,” Financial Times, April 20, 2023 https://www.ft.com/content/18e62451-d066-497e-93dd-f42decd59410; Max Bergmann and Siena Cicarelli, “Open a bank,” Atlantic Council, October 14, 2020,https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/content-series/nato20-2020/open-a-bank/ With that in mind, this section further describes how the Defense, Security and Resilience bank would function by explaining what an MLI is, then exploring the proposed bank’s structure, governance, advantages, and disadvantages. It seeks to provide an objective view of the bank’s feasibility and its potential impact, offering a clear way forward for its creation.

MLIs and their functions

Before discussing the specifics of the proposed Defense, Security and Resilience bank, we need to understand the nature and functions of an MLI. These international financial organizations, formed by multiple countries, provide financial support to member nations. This support primarily comes in the form of loans, guarantees, and grants. By pooling resources from numerous countries (and sharing the risk), MLIs can offer favorable lending terms and promote economic development, stability, and cooperation among member nations.

There are approximately forty MLIs globally,23Johannes F. Linn, “Expand multilateral development bank financing, but do it the right way,” Brookings, November 29, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/11/29/expand-multilateral-development-bank-financing-but-do-it-the-right-way/ with prominent examples including the World Bank, the European Investment Bank (EIB), and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). While each MLI has its unique mandate and focus, they typically share the following key characteristics and functions:

- Ownership and governance: MLIs are owned and governed by member countries, which usually contribute financial resources. The governance structure often includes a board of governors, a board of directors, and an executive management team. Voting rights are proportionate to financial contributions, allowing all members a voice in the decision-making process.

- Financial assistance: MLIs provide financial support to member countries in various forms, such as loans, grants, and guarantees. These financial instruments often carry more beneficial terms than those available in the private market, making them attractive to countries seeking financing.

- Knowledge sharing and capacity building: MLIs often serve as knowledge hubs, offering technical assistance, policy advice, and capacity-building support to member countries. By pooling expertise from various nations, MLIs can help countries implement best practices, improve governance, and strengthen institutional capacity.

- Risk mitigation and credit enhancement: By offering guarantees and other risk-sharing instruments, MLIs can help member countries mitigate risks associated with large-scale projects and attract private investment. Moreover, MLIs’ strong credit ratings often enable them to borrow at advantageous rates, which they can then pass on to their member countries. Furthermore, MLIs tend to carry the nonlegally binding “preferred creditor status,” meaning borrowing nations tend not to default on MLI loans.

- Promoting regional and global cooperation: MLIs can foster cooperation among member countries by financing projects that promote regional integration, economic development, and stability. By working together through MLIs, countries can address common challenges and achieve shared goals more effectively.

Adapting the characteristics and functions of an MLI to focus on defense spending and military cooperation among Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allies could yield substantial benefits. Not only could a Defense, Security and Resilience bank enhance purchasing capabilities, but it could also contribute to achieving significant levels of standardization and interoperability—integral elements that should form part of any loan criteria. Notably, there is currently no MLI globally with a mandate to support defense needs. The proposed bank, offering low-interest loans and additional financial support, stands as a unique innovation. It could bolster allies’ efforts to meet their defense spending commitments, enhance military capabilities, and fortify collective security through the provision of a counter-cyclical financial instrument.

Bank’s structure and governance

The structure of the Defense, Security and Resilience bank must be built on principles of transparency, accountability, and effectiveness. The bank’s governance would be predicated on established norms for MLIs, fine-tuned to align with allies’ unique requirements.

The formulation of a distinct legal framework is vital for the bank to function effectively. As an independent entity serving its members, the bank should operate under a unique charter. This document should detail its mission, objectives, and guidelines. For example, the 1951 NATO Ottawa Agreement, despite conferring broad privileges and immunities to the larger NATO organization, would not align with the specific nature of the proposed bank, given its focus as a market-oriented international financial instrument. Equally, the current EIB charter would not provide the requisite mandate needed by the DSR bank. Therefore, the bank necessitates its own specialized legal structure, tailored to accommodate its unique operational needs. Crucially, there are no barriers within the current allied defense structure(s) that would preclude the creation of this specialized legal foundation for the bank.

At the helm of the organization would be a board of governors, with representatives—usually finance ministers or senior financial officials—from each member nation. Convening at least quarterly, this board would set policies, review the bank’s performance, and approve its budget.

On an operational level, the bank’s daily activities would be overseen by the board of directors (BoD). This group would hold the responsibility for crucial decisions such as loan approvals and project financing. Working closely with a management team, led by a president or CEO appointed by the board of governors, the BoD would translate board of governor-level decisions into strategic actions, effectively aligning the bank’s objectives with the strategic goals of allies. It would be important for national personnel to represent the directors, ensuring allies’ comfort in the knowledge that capability development and investments are conducted in a manner that respects each state’s sovereign rights over such activities.

Creating a robust governance authority as described above is pivotal to ensure both the highest creditworthiness possible, and that funds borrowed are used for defense expenditure in line with the bank’s policy objectives and charter. This authority, leveraging existing mechanisms from institutions like the World Bank, will need to agree on enforcement activities when crafting the bank’s charter. Simultaneously, the Defense, Security and Resilience bank could aid allies to bolster their capacity to spend effectively. Agencies like the NATO Support and Procurement Agency could prove invaluable in aiding nations in conducting either unilateral or multilateral acquisitions, which come with significant and unique tax advantages.

Complementing this structure will be the need for a system of oversight mechanisms to maintain transparency and accountability. This includes both internal and external auditing, a compliance and risk management department, and regular reporting to shareholders. Therefore, creating the bank with the EIB grouping, albeit as a separate legal structure, could achieve efficiencies in terms of leveraging such oversight mechanisms.

The bank’s inception would require a detailed examination of its core components, seeking expert counsel in relevant areas: e.g., tax advisers, law firms, and global investment banks that are experienced in supporting similar institutions. The legal structure, governance, management framework, capital structure, lending instruments, and financing strategy need to be meticulously planned to both provide confidence to nations and to rapidly achieve a AAA credit rating.

Paying for the bank

Inspired by the models of established MLIs, the proposed bank should operate under a cooperative framework, in line with the principles set out in Articles 2 and 3 of the 1949 Washington Treaty.24NATO, “The North Atlantic Treaty,” NATO, April 4, 1949, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_17120.htm#:~:text=Article%202,of%20stability%20and%20well%2Dbeing. This framework would enable allies with strong (i.e., AAA) credit ratings to collectively underwrite borrowings, leveraging their combined capital and assets.25Note that the only NATO nations that have AAA ratings across all major ratings agencies are: Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. This collaborative approach ensures that no single nation is burdened unilaterally.

To address concerns of inequitable burden sharing, it is essential to highlight that the bank’s framework would be designed for shared responsibility and risk mitigation. The global historical record of MLIs shows no instances of default by any Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allied nations, indicating a robust collective fiscal discipline among the allies. This history substantiates the argument against the perceived disproportionate support of weaker nations by AAA-rated members. It would be a collective, well-balanced financial initiative, where the risk is distributed across and minimized for all nations. Furthermore, while it is important for the bank to have a AAA rating, such a rating does not exclusively come from AAA-rated members of the bank. Rather, the bank’s mandate, charter, governance structure, modes of operation, and management expertise all contribute to the rating the bank will gain. In other words, this is not solely about AAA-rated nations bolstering non-AAA-rated countries through a third party. Once a AAA rating is achieved, the bank would need to work closely with the appropriate rating agencies to makes sure that its AAA rating is sustained.

For fiscally conservative allies concerned about supporting less financially disciplined partners, the Defense, Security and Resilience bank presents a mitigated risk model. The collective creditworthiness and historical reliability of nations in fulfilling their wider MLI financial obligations significantly reduce the risk associated with the bank. Therefore, allies such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark can participate with the assurance that their strong credit ratings are part of a collective buffer, rather than being singularly exploited. The bank’s ability to issue debt at competitive rates in the capital markets, owing to this collective strength, will enable the efficient channeling of funds toward essential defense expenditures, overseen by the bank, its risk team, and investment oversight staff.

However, the bank would need to account for its overhead, including staff, infrastructure, and information technology systems. These expenses would be largely self-funded through the interest spread on loans extended to borrowing allies. Any additional income could then be channeled toward supporting further alliance activities.

The bank’s financial model would follow a typical MLI approach, where the bank borrows from capital markets at one rate, let’s call this Rate A (for instance, 2.9 percent),262.9 percent is suggested as this is a yield consistent with comparable debt issuance that has been auctioned through the European Commission and/or syndicated through the World Bank. See European Commission, “EU debt securities data,” European Commission, accessed April 1, 2024, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/eu-budget/eu-borrower-investor-relations/transactions-data_en; and “Impressive Demand for World Bank’s EUR 3 Billion 10-Year Sustainable Development Bond,” press release, World Bank, January 11, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/01/11/impressive-demand-for-world-bank-s-eur-3-billion-10-year-sustainable-development-bond. and lends to those allies requiring capital at another slightly higher rate, Rate B (for example, 3.0 percent). Rate B would be substantially lower than Rate C, the rate at which allies would need to borrow when individually accessing capital markets (see table 2).

Table 2: Capital market ten-year bond yield rates of NATO allies

The difference between Rates A and B—the interest spread—would cover the bank’s operational costs. Any excess funds, which could originate from interest payments on paid-in capital (i.e., what each shareholder (ally) has invested in the bank), could be deposited within the bank. These funds could then be used by the bank’s members within the framework of defense, security, and resilience spending, offering an added layer of financial flexibility. However, to bolster risk management and align borrowing with strategic objectives, the bank will employ tailored covenants as safeguards, ensuring funds are used purposefully and within a disciplined financial framework.

While table 2 highlights that the vast majority of NATO nations would financially benefit by borrowing through the DSR bank, it remains essential to emphasize the principle of equal treatment in the bank model. Not only would nations striving to meet the 2 percent GDP target benefit from the initiative, but allies already fulfilling that requirement could also enjoy lower borrowing costs, reinforcing the spirit of unity and collective security, while creating domestic fiscal headroom to balance competing domestic tax and spending needs.

Incentives

Beyond the immediate low interest savings and hedging strategies that a Defense, Security and Resilience bank could offer, its establishment promises an array of compelling incentives for a diverse spectrum of participants. The bank would transcend the traditional confines of a fiscal instrument and should be viewed as a strategic tool that could bolster defense spending efficiency and fortify international relations. The wider incentives of the bank’s creation include:

- Transforming defense spending dynamics: The proposed bank is designed to complement—not replace—national defense, security, and resilience spending. By pooling resources, it would depoliticize defense funding, shifting the focus from national budgets to a unified alliance strategy. While direct defense budgets remain vital, the bank would offer an alternative funding avenue, alleviating pressure on national finances and internal politics. This collective financing model could reshape the defense spending narrative, allowing nations to demonstrate their commitment without heavily relying on politically sensitive budget increases.27For an explanation of why seeking greater tax revenue by allies at a domestic level is unlikely to be successful to support additional defense spending, see Florian Dorn, Niklas Potrafke, Marcel Schlepper, European Defence Spending in 2024 and Beyond: How to Provide Security in an Economically Challenging Environment, EconPol Policy Report 45, ifo Institute, 2024, https://www.cesifo.org/en/node/80141. The bank’s role would enable member states to leverage shared resources, enhancing collective security in a way that acknowledges each nation’s unique political and economic constraints. Ultimately, this approach could foster a more cohesive stance within NATO and beyond, offering a pragmatic solution to the challenges of defense spending while strengthening alliance-wide resilience.

- Strengthening international organizations: The Defense, Security and Resilience bank concept represents a contemporary application of international cooperation, reinforcing the relevance and importance of multinational organizations in the current political climate.

- Indicator function: Similar to catastrophe bonds, DSR bonds issued through the bank could offer financial markets an indicator of the likelihood of military conflict, providing valuable insights for risk assessment and strategic planning.

- Capital market deterrence: The bank could introduce an innovative new international relations concept: capital market deterrence. By offering Defense, Security and Resilience bonds on the open market, rival nations—or entities within them—could inadvertently (or advertently) finance allies’ defense. This financial stake could deter conflict, as hostilities may risk bond repayments. While the probability of this mechanism’s impact on deterrence by itself is low, taken in combination with wider Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific deterrence efforts does make this suggestion greater than zero. However, it bears remembering that World War I disproved the theory of Sir Normal Angell, a British author and Nobel Peace Prize recipient, that financial integration could guarantee peace.28Ali Wyne, “Disillusioned by the Great Illusion: The Outbreak of Great War,” War on the Rocks, January 29, 2014, https://warontherocks.com/2014/01/disillusioned-by-the-great-illusion-the-outbreak-of-great-war/ Thus, while capital market deterrence could supplement traditional defense mechanisms, maintaining a robust defense posture remains crucial.

- Grand strategic response: The bank could be positioned as a response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Although the investment activities differ, the strategic aim of using financial entities to maintain the balance of power should not be ignored.

- High-quality liquid assets: Debt securities issued by the bank could be designated as high-quality liquid assets by global financial regulators. This, coupled with the potential inclusion of these securities in bond indices, could significantly stimulate market demand.

- Existing financial infrastructure: Major global investment banks with a history of advising sovereign entities, supranational organizations, and agencies on bond underwriting and distribution could become natural partners for the bank. Their vested interest in the bank’s success, complemented by their existing support networks, could expedite the bank’s establishment, and ensure its efficient operation.

- Counter-cyclical financial instrument for defense stability: The bank is envisioned to act as a vital counter-cyclical tool, which is particularly effective during economic downturns. In periods of recession, when countries face fiscal constraints, maintaining defense spending can become particularly challenging. This is where the bank’s role becomes crucial. By providing low-interest loans spread over very long time frames, the bank would offer a more cost-effective option for defense financing compared to the typically higher interest rates nations would face when borrowing domestically during economic contractions.

The comparative advantage of borrowing from this bank lies in its ability to offer more favorable loan terms than most domestic borrowing options available to countries. This advantage is not just in terms of lower interest rates and lending duration but also in the commitment and consistency it brings to defense spending. History shows that investments made through similar MLIs tend to be more stable and less prone to cuts compared to unilateral domestic projects, which are often the first to face reductions in times of economic hardship.

Thus, the Defense, Security and Resilience bank would serve as a financial buffer, enabling allies to sustain their defense commitments without the immediate financial strain that would typically accompany such spending in times of fiscal constraints. This approach ensures that the collective security of those allies across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions is not compromised during economic downturns. Essentially, the bank would offer a strategic financing option for defense and strengthen the resilience of the Alliance’s defense commitments against the vagaries of economic cycles.

What the bank would do

Put simply, the DSR bank could perform four core functions:

- direct lending for defense needs;

- currency and resource hedging options to protect against market volatility;

- lease financing for armaments trade between allies; and

- guarantees that underwrite commercial supply chain financing.

Direct lending

To illustrate how the bank model would work, let’s revisit the case of Poland from 2002. At that time, Poland made a significant commitment to purchase forty-eight F-16 fighter aircraft from the American aerospace firm Lockheed Martin, at a total cost of $3.8 billion. This substantial purchase was made possible through a direct loan from the US Treasury. Congress sanctioned a thirteen-year fixed-rate loan at an interest rate of 5 percent—the same as the rate for the ten-year US Treasury note at that time.29Peter Evans, “The financing factor in arms sales: the role of official export credits and guarantees,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, November 2022, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/539-560%20App.13E_0.pdf Over the loan’s duration, Poland’s interest burden from this deal was, per an estimate, approximately $3.47 billion.30Interest was calculated using the formula for annual compound interest: A = P (1 + r/n) ^ nt; A is the amount of money accumulated after n years, including interest; P is the principal amount (the initial amount of money); r is the annual interest rate; n is the number of times that interest is compounded per year; t is the time the money is invested for, in years. In this case, we’re assuming interest is compounded annually, so n = 1.

Fast forward to today, and the borrowing landscape looks quite different. The yield on a ten-year US Treasury bond now stands at around 4.30 percent.31As of July 4, 2024. Meanwhile, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) under the World Bank—which could serve as a reasonable proxy for the kind of interest rates a DSR bank might offer—has a ten-year bond with a yield of 3.0 percent.32World Bank, “Impressive demand for World Bank’s EUR 3 billion 10-year sustainable development bond,” World Bank, January 11, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/01/11/impressive-demand-for-world-bank-s-eur-3-billion-10-year-sustainable-development-bond

In the current lending context, Poland’s borrowing costs would change significantly. If it were to secure a loan from the US government at the current rate of 4.3 percent, Poland would be liable for roughly $2.77 billion in interest over a thirteen-year period. However, if Poland were to borrow from the proposed Defense, Security and Resilience bank at a rate of 3.0 percent, the total interest payable would decrease to approximately $1.78 billion.

Table 3: Breakdown of borrowing costs for Poland and F-16 financing

In today’s financial environment, the existence of a DSR bank could potentially offer Poland substantial savings: around $1 billion in interest payments alone. Moreover, if Poland were to procure the F-16s through NATO’s Support and Procurement Agency, it could realize additional benefits through unique tax incentives.

To place this into further context, it is worth noting that intra-allied defense sales accounted for around $30 billion during 2018/2019. If such trade were financed through the Defense, Security and Resilience bank versus national financing, NATO allies trading between themselves could save almost $500 million annually in interest payments alone (see table 4). Noting that defense borrowing tends to be spread over many years (see the Polish F-16 example), such interest savings soon start to compound and become billions of dollars.

Table 4: Intra-allied defense sales (2018/2019)

Currency hedges

In addition to direct lending, acting as a currency hedge for large procurements is another potential use of the Defense, Security and Resilience bank. Take, for instance, the shock to the British pound in 2022: in early August of that year, one US dollar (USD) bought 81 pence. Yet by the end of September, the currencies were almost at parity, with a dollar fetching 93 pence. This sudden devaluation of the pound by nearly 15 percent meant that UK procurement professionals, sourcing long lead time armaments from US suppliers, had to potentially find an additional 15 percent to pay those dollar-denominated invoices.

A Defense, Security and Resilience bank would provide a mechanism to hedge against such currency fluctuations. Here’s how:

Step 1: The UK, procuring armaments from a US company, borrows from the bank in pound sterling (GBP). Upon securing the loan, the UK initiates immediate repayments to the bank in GBP, while the borrowed funds are simultaneously converted in full to US dollars at the current spot exchange rate. This upfront-conversion strategy serves as a safeguard against future exchange rate volatility. Given that defense procurements such as jets or submarines often span years if not decades, this could offer substantial protection.

Step 2: The UK might pay an initial 20 percent down payment to the vendor in US dollars, investing the remaining 80 percent in low-risk, USD-denominated assets such as US treasury bonds.

Step 3: As the vendor fulfils contractual milestones, those dollar-denominated investments are easily liquidated and the payments are made in dollars, thereby shielding the UK from sudden currency shocks.

Nonetheless, such a strategy is not without its risks, including interest rate, liquidity, counterparty, operational, and exchange rate volatility. These risks emerge from the UK’s reinvestment of borrowed funds in USD low-risk assets over the procurement period. However, a multipronged approach can help mitigate such concerns:

- Interest rate risk: The use of financial instruments including interest rate swaps or options can help manage interest rate fluctuations.

- Liquidity risk: Investment in highly liquid assets and diversification of the portfolio can ensure funds are available when needed.

- Counterparty risk: Selecting investment counterparts with high credit ratings can reduce the risk of default.

The Defense, Security and Resilience bank could provide allies with a unique strategy to offset future currency fluctuations, ensure predictable future defense budgets (as repayment remains in the original debt-issued currency), and distribute the underwriting risk, potentially lowering the cost of capital. Such a currency hedge would also allow allies to maintain their foreign currency reserves, offering a platform for either unilateral or multinational borrowing. However, it’s crucial to remember that such a strategy, with its complexity and inherent risks, would necessitate the stewardship of experienced banking professionals combined with defense experts. The bankers would need to navigate the intricacies of interest rate swaps and manage liquidity and counterparty risks, while their defense professional colleagues would focus on making informed decisions about the investment of borrowed funds. But with the right expertise and governance, the bank could play a pivotal role in promoting financial stability and procurement efficiency among allies in both Euro-Atlantic Council and Indo-Pacific regions.

Lease financing

The introduction of the bank could usher in a new paradigm for defense expenditure that goes beyond traditional procurement methods: the facilitation of strategic armaments leasing between shareholders. The concept of leasing allows an ally with robust defense manufacturing capabilities (Ally X) to construct and maintain significant armaments such as tanks, aircraft, or naval vessels, which are then leased on a long-term basis to another ally (Ally Y), who may lack the means or capacity to produce such assets domestically.

This leasing arrangement allows for mutual benefits: it manifests as an asset on both allies’ balance sheets, enhancing their defense expenditure without necessitating an immediate, sizable outlay of funds. For Ally Y, it provides an efficient way to rapidly enhance its military capabilities. On the other hand, Ally X can offset some of the costs of production through the lease payments.

The bank, in this case, could serve as the financial intermediary and guarantor of these arrangements. Its mandate could include establishing a robust framework for these agreements, ensuring compliance with allies’ strategic objectives, assessing financial viability, and mitigating risks. It could also provide consultation and advice on the structure of such deals to guarantee they’re mutually beneficial, economically sound, and in line with the defense and foreign policy objectives of the allies involved.

While national import-export banks often play a crucial role in facilitating international trade deals similar to what is being proposed here, their mission and operations might not be aligned closely enough with the specific needs of defense procurement and leasing arrangements within the global defense context. The complexity of these arrangements—which encompass diplomatic, financial, and military dimensions—necessitate an organization like the Defense, Security and Resilience bank, which is specifically tailored to understand and address such multifaceted challenges. Moreover, the sheer cost of defense acquisition often outstrips the balance sheets of national import-export banks. Indeed, as one senior official from a NATO nation recounted in our discussions, their nation used its import-export bank to facilitate the financing of armaments to a non-NATO nation and through that one deal maxed out its import-export bank credit capacity—in other words, individual nations do not always have the capacity to resource multiple defense acquisition efforts. This is something the proposed Defense, Security and Resilience bank could achieve on behalf of allies due to the size of its collective balance sheet.

Supply chain financing

The fourth element of the Defense, Security, and Resilience (DSR) bank’s mission will be to help address the targeted credit crunch facing defense supply networks, particularly among smaller Tier 2–4 suppliers. Traditional commercial banks are increasingly reluctant to lend to these firms due to compliance risks, including Anti-Money Laundering (AML), Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations, and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards. This lack of liquidity poses a critical threat to the resilience and scalability of defense supply networks, jeopardizing the production of critical components and the ability of nations to ramp up defense production capabilities.

The DSR bank will be able to deploy a comprehensive framework of supply chain financing guarantees designed to de-risk commercial bank lending and encourage both commercial and non-traditional financial institutions to extend credit across the defense ecosystem. The key mechanisms include:

- Risk Underwriting: The DSR bank will act as a guarantor, underwriting a significant portion of the risk associated with commercial loans to defense suppliers. This reduces the perceived risk for commercial lenders, enabling greater credit flows.

- Tiered Guarantee Structures: Guarantees will be calibrated across different supplier tiers:

- Tier 1 (Primes): Large defense contractors benefit from easier access to financing for large-scale projects.

- Tiers 2–4 (SMEs, Component Manufacturers, and Startups): Smaller firms receive targeted guarantees that address their unique financial vulnerabilities, ensuring they can access working capital and funding for innovation.

- Private Sector Participation: In addition to commercial banks, institutional investors—such as pension funds and other private entities—will be encouraged to provide direct supply chain financing underpinned by the bank’s guarantees, further expanding access to capital for critical suppliers.

- Standardization and Compliance Support: The DSR bank will offer a compliance support framework to help suppliers meet regulatory requirements. By addressing AML, KYC, and ESG standards proactively, the Bank ensures that more loans qualify for guarantees.

Through this multi-faceted approach, the DSR bank will help unlock capital flows to critical suppliers, ensuring that all tiers of the defense supply chain—from established primes to innovative startups—can operate effectively. By stabilizing supply chain liquidity, the DSR bank not only supports immediate production needs but also fosters long-term resilience and innovation within the defense sector.

Building the balance sheet

Establishing a Defense, Security and Resilience bank requires the highest political and financial leadership. On the political side, getting the bank established will require engaged effort, direction and guidance from the most senior parts of government with elected ministers taking an active leadership role. On the financial side, vigilant balance sheet construction, with allies underwriting the project, will be critical.

The balance sheet would comprise a blend of cash or paid-in capital, and obligations or callable capital. Together, these constitute the “subscription capital,” which can be drawn upon as needed. The balance sheet would underpin the issuance of DSR bonds, the proceeds of which could be used by allies seeking to enhance their defense spending at low interest rates. The bonds could be unsecured, relying on nations collective financial standing, or secured by subscription capital, potentially reducing the cash commitment required from an underwriting ally. These bonds could also span multiple decades, as war bonds have done in the past, and which many nations are unable to achieve unilaterally.

To provide a practical context for these proposals, it’s worth noting that all Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allies already participate in at least one MLI such as the World Bank or the European Investment Bank, and therefore all potential shareholder governments have relevant MLI experience. Table 5 presents the average contribution of NATO allies as one-off, paid-in capital investments to their existing MLIs.

Table 5: Average ally contribution to MLIs

Sources: MLIs used to establish average paid-in capital contributions of allies include the Asian Development Bank (ADB), African Development Bank Group (AfDB), the AIIB, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), EIB, Inter-American Development Bank (AIDB), International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), Nordic Investment Bank (NIB), and Caribbean Development Bank (CDB); World Bank population data.

If the averages from table 5 were applied to the Defense, Security and Resilience bank, one might expect a balance sheet with a minimum of around $8.36 billion of paid-in capital. Typically, paid-in capital represents anywhere between 10 percent to 15 percent of the overall balance sheet value. Therefore, one can assume that $8.36 billion could represent 12.5 percent of the total balance sheet value. Combining this with the other 87.5 percent of callable capital (or $56 billion), the bank could initially create a subscribed capital total of up to $64 billion, a relatively modest amount when compared to the subscribed capital of existing MLIs (see table 6). One could see this figure ($64 billion) as a starting point for the bank, with future capital calls being made to expand the balance sheet should allied shareholders so wish.

However, it is this blend of paid-in and callable capital that is pivotal in securing a AAA credit rating, thereby enabling borrowing at remarkably low rates. To foster confidence in achieving and maintaining this rating, the bank’s gearing of debt to equity should adhere to standard MLI ratios, likely starting at 1:1. Over time, this could evolve, potentially aligning more closely with institutions like the European Investment Bank, which maintains a debt-to-equity ratio nearer to 2.5:1.

Table 6: Subscribed capital totals and average of existing MLIs

Sources: Asian Development Bank (ADB), African Development Bank Group (AfDB), the AIIB, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), EIB, Inter-American Development Bank (AIDB), International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), Nordic Investment Bank (NIB), and Caribbean Development Bank (CDB).

Payment by nations

To mitigate the immediate fiscal pressures on allies, the proposed contributions toward the bank’s paid-in capital (approximately $8.36 billion) could be dispersed over a four-year time frame. This phased approach would afford nations the opportunity to carefully manage their investments, bolstering the sustainability and feasibility of their commitments.

Contributing to the bank’s paid-in capital offers NATO allies specifically, a strategic avenue to help fulfil their obligation of 2 percent GDP defense spending while enhancing overall financial efficiency. This approach is particularly beneficial for smaller nations like Luxembourg or Iceland, which may not have large standing forces but can demonstrate alliance solidarity through such financial contributions. More significantly, this capital should not only count toward the 2 percent defense commitment but also amplify its impact. When nations invest in the bank and subsequently borrow for defense spending, they effectively leverage their contributions, achieving more with their financial resources. This creates a multiplier effect, allowing taxpayer money to yield greater defense capabilities at potentially lower costs. Such a system promotes equitable burden sharing, as each member’s investment in the bank contributes to more affordable borrowing rates for all, ultimately serving the collective defense objectives more effectively.

Furthermore, allies would retain full autonomy over their pledges to the bank, whether in the form of paid-in capital, callable capital, or a combination of the two. However, in a manner akin to the World Bank model, pledges should be scaled to determine influence within the bank. This model positions governments as both shareholders and borrowers, fostering shared responsibility and collective gain. The more an ally commits to the bank, the greater their influence at the governance level, as is standard practice in all MLIs.

However, a more ambitious idea would be to use those seized Russian Central Bank funds currently being held in Belgium through Euroclear and essentially utilize said funds to capitalize the Defense, Security and Resilience bank. This is clearly an escalatory measure but given the current context of the war in Ukraine, there could be Allied political consensus found around the notion of: raising a Defense, Security and Resilience bank, having the Russians pay for it, and using collective loans to buy armaments that support Ukraine as well as providing additional financing to support allied nations prepare to defend themselves from potential Russian aggression.33Nicolas Véron, “Cash keeps accumulating at Euroclear bank as a result of sanctions on Russia,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, January 9, 2024, https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/2024/cash-keeps-accumulating-euroclear-bank-result-sanctions-russia

Mitigation strategies

As the proposed Defense, Security and Resilience bank is arguably poised to reshape defense, security and resilience financing, it is crucial to anticipate potential challenges and devise strategic mitigation measures. Financial relations between EU and non-EU nations have been addressed previously, but the complexities involved span across fiscal and political realms, operational difficulties, and the execution of strategic approaches. The following table lays out these challenges, categorized into three broad sections: fiscal and political considerations, overcoming operational challenges, and strategic mitigation approaches. Each challenge is accompanied by a mitigation measure, providing a path to navigate these obstacles and ensure the venture’s success.

Table 7: Fiscal, political, operational, and strategic aspects to address

While the European Investment Bank (EIB) provides a strong foundation in financing and governance, the proposed Defense, Security, and Resilience (DSR) Bank would benefit from being established as a separate legal entity with its own credit rating potentially under the EIB framework. This structure would allow the DSR Bank to leverage the EIB’s respected institutional infrastructure and financial expertise while focusing on a distinct mandate that aligns more closely with global security priorities.

Although there is some overlap in membership between NATO allies and the EIB’s shareholders (the twenty-seven EU member states), key partners in transatlantic and Indo-Pacific regions—including Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, Turkey, Canada, Australia, and Japan34European Investment Bank, “Shareholders,” European Investment Bank, Accessed April 1, 2024, https://www.eib.org/en/about/governance-and-structure/shareholders/index.htm—are not EU members, but it will be vital that such nations are invited to be shareholders in the DSR Bank in order to maximize its credibility. This broader coalition of partners would enable the DSR Bank to respond to collective defense and resilience priorities beyond the EIB’s EU-centric focus on economic cohesion and regional integration.

Moreover, the EIB’s mandate and legal framework are not structured to prioritize defense, security, and resilience objectives. Establishing the DSR Bank as a separate entity within the EIB would ensure that it could develop specialized competencies and operational frameworks tailored to these strategic areas while maintaining financial autonomy and creditworthiness. By having its own credit rating, the DSR Bank would attract a wider range of investors suited to its security-focused mission, strengthening its capital base and lending capacity.

This approach allows the EIB and the DSR Bank to work within their respective areas of expertise while opening pathways for collaboration where their mandates intersect. Such a setup not only respects the EIB’s current structure and purpose but also creates an agile and focused institution capable of addressing the emerging defense and resilience needs of allied nations in an increasingly complex global environment.

In summary, the potential challenges the DSR bank could encounter are multifaceted and navigating them will require a mix of fiscal prudence, political diplomacy, and operational acumen. However, the broad strategic mitigation measures outlined above provide an initial framework for overcoming these obstacles. The bank’s success lies in its ability to foster a sense of shared responsibility and mutual benefit among allies, while working within existing fiscal norms and addressing each nation’s unique needs. By undertaking this approach with diligence and adaptability, the bank can serve as a powerful tool in enhancing allied defense, security and resilience capabilities and fostering a more secure future for allied nations across the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions.

Founding members and an approach to bond issuance

The establishment of the Defense, Security and Resilience bank depends on founding members with strong credit ratings to underpin its financial stability and operations. While the ultimate goal is to allow membership from all Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific allies, the bank will initially require a core group of anchor nations to build its balance sheet and governance structure. The Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF)—a coalition of ten allied nations with robust credit ratings—along with the United States and Japan, could form this foundational group.35Lord Stuart Peach, Robbie Boyd, and Ed Arnold, “Stretching the Joint Expeditionary Force: An Idea for Our Times,” RUSI, September 8, 2023, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/stretching-joint-expeditionary-force-idea-our-times; The JEF is comprised of the United Kingdom, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. The appendix provides a breakdown of NATO allies and their current sovereign credit ratings. This JEF-led approach would establish a credible foundation and could feed into the European Investment Bank (EIB) framework noting that the Defense, Security and Resilience Bank must be created as a separate legal entity with its own credit rating to ensure independent governance and operational flexibility. Once the bank’s charter is in place by those anchor nations, remaining NATO, EU, and Indo-Pacific allies and partners would be invited to join as shareholders, creating an inclusive and resilient institution for defense, security, and resilience financing.

Regardless of which nations initially anchor the bank, there are some lessons from the recent European Commission’s debt issuance,36Gegory Claeys, Conor McCaffrey, Lennard Welslau, “The rising cost of European Union borrowing and what to do about it,” Bruegel, May 31, 2023, https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/rising-cost-european-union-borrowing-and-what-do-about-it driven by a collective response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which the Defense, Security and Resilience bank should observe including:

- Refining the way bonds are sold: The way a bank sells its bonds can impact the costs of borrowing. Currently, the European Parliament has suggested that the European Commission rely less on “syndicated transactions,”37European Parliament, “The rising cost of European Union borrowing and what to do about it,” European Parliament, 2023 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2023/749450/IPOL_IDA(2023)749450_EN.pdf where a group of banks are preselected to underwrite the debt, and shift more toward auctions, where different parties bid to buy the bonds. For the Defense, Security and Resilience bank, this strategy could reduce the power of the banks selling the bonds (primary dealers) and help get better prices for the bank’s debt. In simpler terms, this approach is like choosing to sell your house by open bidding instead of one real-estate agent.

- Improving the trading environment: Making DSR bonds easier to buy and sell (e.g., increasing their liquidity) could also help lower borrowing costs. This can be achieved by focusing on issuing short-term bonds first, which are generally more attractive to traders. Also, the bank could encourage the inclusion of DSR bonds in popular bond indices, making them more attractive to a wider range of investors. It might also be possible for the bonds to have tax advantages akin to US municipal bonds.38J.B. Maverick, “How are Municipal Bonds Taxed?” Investopedia, March 21, 2024, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/060215/how-are-municipal-bonds-taxed.asp

- Strengthening institutional support: The bank’s credibility and attractiveness to investors could be further enhanced by aligning its operations closely with the key principles of sovereign entities, such as clear repayment strategies. This would make DSR bonds more like government bonds, which are often seen as safer investments.

- Managing interest costs efficiently: The European Commission has found that its interest costs were higher than expected. To avoid a similar situation, the Defense, Security and Resilience bank should ensure its budgeting processes accurately account for the cost of interest.

- Keeping the option to borrow: Just as a business might have a line of credit it can use when needed, the bank should maintain the ability to borrow as a permanent tool. This allows it to have funds available not just for emergencies, but also for significant initiatives or opportunities that may arise.

- Clear communication: The bank needs to reassure investors that its debt is a long-term, sustainable part of its strategy. This could help to increase investor confidence and result in better loan terms.

By applying these lessons from the European Commission’s debt issuance strategy and experience,39European Parliament, “The rising cost of European Union borrowing and what to do about it,” European Parliament, 2023 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2023/749450/IPOL_IDA(2023)749450_EN.pdf the Defense, Security and Resilience bank can aim to secure better loan terms and establish itself as a stable and trustworthy player in the global bond market.

Conclusion

The proposed Defense, Security and Resilience Bank, shaped by an understanding of the complex interplay of defense, finance, and international relations, could be a game-changing development for global defense, security and resilience. The blueprint of the bank outlined above provides an overview of its anticipated inception, with a focus on creating a financially sound, accountable, and transparent institution that can support the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific defense needs. The road to its establishment is paved with intricate decisions and significant coordination among nations at the highest political levels, but with a clear vision and strategic execution, it could play a critical role in strengthening Allies collective defense for the foreseeable future.

As a next step, a small group of anchor nations should collaborate and seek to develop a charter for the bank with a view to inviting additional nations to join the bank as shareholders and seeing operations begin in or around 2027.

Appendix