Appointment signals administration’s intent to wind down war, get tough with Pakistan

The appointment of Zalmay Khalilzad as US President Donald J. Trump’s special representative on Afghanistan sends a clear signal that the US administration is serious about winding down its involvement in the war in Afghanistan. By putting a longtime critic of Pakistan in charge of the peace process, the Trump administration has also put Islamabad on notice that it has little patience for its support for terrorists in Afghanistan.

Khalilzad’s appointment is a “good sign that the administration recognizes that if it’s going to be serious about trying to achieve a negotiated settlement, that requires having some real diplomatic muscle applied to the task,” said Laurel E. Miller, a senior foreign policy expert at the RAND Corporation. “That means having a clearly empowered individual who has the backing of the secretary of state… the White House, and an explicit mandate to achieve a negotiated settlement.”

Omar Samad, a former ambassador of Afghanistan to France and Canada, said the appointment sends a “serious message” to the region, particularly Pakistan.

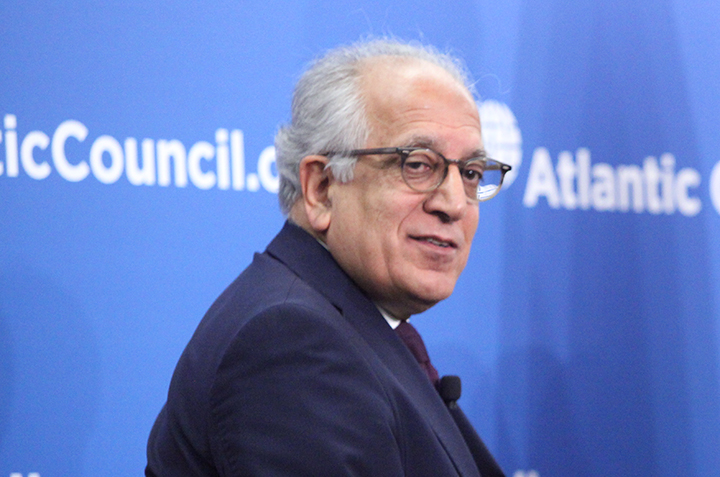

US Secretary of State Michael Pompeo announced the appointment of Khalilzad, an Atlantic Council board director who served as the US ambassador to Iraq, Afghanistan, and the United Nations, while traveling to Pakistan on September 4.

“Ambassador Khalilzad is going to join the State Department team to assist us in the reconciliation effort, so he will come on and be the State Department’s lead person for that purpose,” Pompeo said.

Khalilzad will “be full-time focused on developing the opportunities to get the Afghans and the Taliban to come to a reconciliation. That will be his singular mission statement,” Pompeo said.

Rakesh Sood, a former ambassador of India to Afghanistan whose term in Kabul overlapped with Khalilzad’s, noted that Gen. John Nicholson, the outgoing commander of US and NATO forces in Afghanistan, did not have a single meeting with Trump in over twenty months. This fact, Sood said, underscores the importance of empowering advisers.

Miller, who until June 2017 was the acting special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan at the State Department, said Khalilzad would need to insist on having a team and the resources to execute his mission.

Getting tough with Pakistan

While Trump ramped up the number of US troops in Afghanistan, he has made no secret of his desire to end the US involvement in a war it has been waging with scant sign of victory for the past seventeen years.

In his farewell remarks, Nicholson notably emphasized the importance of peace negotiations. “It is time for this war in Afghanistan to end,” he said.

In an effort to achieve that end goal, the Trump administration has entered into bilateral peace talks with the Taliban and begun to turn the screws on Pakistan—a country that provides material support and safe havens to terrorist groups that operate in Afghanistan. Pakistan denies providing such support while pointing to the sacrifices it has made fighting terrorists on its own soil and its support for the US-led mission in Afghanistan.

Trump kicked off 2018 with a tweet that set the tone for his administration’s position on the region. “The United States has foolishly given Pakistan more than 33 billion dollars in aid over the last 15 years, and they have given us nothing but lies & deceit, thinking of our leaders as fools. They give safe haven to the terrorists we hunt in Afghanistan, with little help. No more!” the president tweeted on January 1.

The same day, Khalilzad endorsed Trump’s sentiment in a tweet of his own. “@POTUS is right on Pakistan. Success in #Afghanistan and in war against terror require a change in policy of Pakistan which pretends to be a partner but behaves as an enemy. Pakistani double game must stop. Time to shift to a coercive strategy,” he tweeted.

Trump’s tweet should have come as no surprise to those who have been paying close attention to his words. In a speech in August 2017, Trump said: “Pakistan has much to gain from partnering with our effort in Afghanistan. It has much to lose by continuing to harbor criminals and terrorists.”

“We have been paying Pakistan billions and billions of dollars, at the same time they are housing the very terrorists that we are fighting. But that will have to change. And that will change immediately,” he added. “No partnership can survive a country’s harboring of militants and terrorists who target US service members and officials.”

The Trump administration is attempting to change Pakistan’s behavior using some of the methods that have been tried—with little success—before.

On September 1, the Trump administration cut off $300 million in Coalition Support Funds (CSF) to Pakistan citing its failure to act against terrorists.

In Pakistan on September 5, Pompeo met the country’s newly minted Prime Minister Imran Khan, Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi, and Army Chief Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa. Pompeo said after the meetings that the talks focused on the opportunity to “reset” the bilateral relationship. Khalilzad participated in those meetings.

Khalilzad’s vision

In an interview with the New Atlanticist in 2016, Khalilzad suggested that the United States should be prepared for some hard work in Afghanistan. “We are in a period of wanting to avoid great exertions like the ones in Iraq and Afghanistan,” he said at the time. “While I think that the right lesson to learn from Iraq and Afghanistan is that big projects such as these two need to be done very selectively and rarely, we also need to recognize that we might have to do them again. We need to ask: what capabilities do we need to retain should it be necessary to undertake such an effort again; what weaknesses were identified in our approaches and our capabilities that need to be addressed; and what are the things that we must avoid and not repeat?”

Reflecting on the mistakes of the past, Khalilzad said that “the combination of not dealing with the sanctuary issue [for terrorists in Pakistan] and being slow to build Afghan institutions over time worsened the security situation in Afghanistan and raised dramatically the costs of securing Afghanistan and achieving strategic success there.”

On the question of reconciling with the Taliban, Khalilzad suggested that the Afghan government pursue a strategy that would “respond to, take advantage of, and shape internal developments in the Taliban.” The announcement in 2015 of the death of the Taliban’s leader Mullah Omar—news that the Taliban leadership had kept under wraps for two years—triggered infighting within the group causing it to splinter into several factions.

The Taliban has since ramped up its military offensive in Afghanistan. In August, the group launched a significant offensive to take control of the strategic southeastern city of Ghazni.

Khalilzad said in our 2016 interview that the Taliban could be convinced to work toward peace “when they feel that they are losing the war, where they are fragmenting, where their international support declines, where Afghanistan’s economic situation improves and its security forces do better and better.”

“The facts on the ground are key in terms of propensity or prospects for reconciliation,” he said.

Noting that the military has the upper hand in Pakistan, Khalilzad said that if Pakistan is serious about reconciliation it must clamp down on terrorist safe havens. “You cannot facilitate peace if you are facilitating war,” he said. “That should be the objective of the United States and China: to get Pakistan to shut down the facilities for war.”

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @AshishSen.

Image: Zalmay Khalilzad, a former US Ambassador to Afghanistan, Iraq, and the United Nations, and a current member of the Atlantic Council’s Board of Directors, discussed his memoir, The Envoy: From Kabul to the White House, My Journey Through a Turbulent World, at an event hosted by the Council’s South Asia Center on April 20. (Atlantic Council/Victoria Langton)