Cloudbusting: Policy for evaluating trust in compute infrastructure

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- A shared cloud computing vocabulary

- Cloud computing and artificial intelligence

- Building trust

- Digital sovereignty and data localization

- Implications for cybersecurity and AI

- Conclusion

- Author and acknowledgements

Executive summary

Placing trust in cloud computing is no longer optional. Cloud computing is essential to critical infrastructure, commercial, and government operations.1Tianjiu Zuo, Justin Sherman, Maia Hamin, and Stewart Scott, Critical Infrastructure and the Cloud: Policy for Emerging Risk, Atlantic Council, July 10, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/critical-infrastructure-and-the-cloud-policy-for-emerging-risk/. Outages over the past few months emphasize the vitality of cloud services to modern economies and essential government services.2Lily Hay Newman, “What the Huge AWS Outage Reveals About the Internet,” Wired, October 20, 2025, https://www.wired.com/story/what-that-huge-aws-outage-reveals-about-the-internet/. As cloud adoption and transformation continue, policy attention should shift from the question of whether to simply trust cloud computing to the methods for establishing and verifying that trust.

The stakes will only continue to increase as artificial intelligence systems, which have been identified by the US, China, and the European Union as essential national priorities, continue to utilize cloud infrastructure for development and deployment.3“Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan,” Executive Office of the President of the United States, July 23, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Americas-AI-Action-Plan.pdf; “Global AI Governance Action Plan,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China,” July 26, 2025, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng./xw/zyxw/202507/t20250729_11679232.html; “The AI Continent Action Plan: Shaping Europe’s Digital Future,” Commission to the European Parliament, April 9, 2025, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ai-continent-action-plan. Sophisticated and unsophisticated threat actors continue to target cloud computing systems, striking rapidly, globally, and opportunistically. 4“Top Threats to Cloud Computing 2024,” Cloud Security Alliance: Top Threats Working Group, August 5, 2024, https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/artifacts/top-threats-to-cloud-computing-2024. These cloud incidents can result in data theft, financial losses, and operational disruptions. Even accidents require rapid coordination and information sharing to ensure systems can get back up and running as quickly as possible.5An Outage Strikes: Assessing the Global Impact of CrowdStrike’s Faulty Software Update, 118th Cong. (2024) (written testimony of Adam Meyers, Senior Vice President, Counter Adversary Operations, CrowdStrike), https://homeland.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/2024-09-24-HRG-CIP-Testimony-Meyers.pdf

Ensuring trust in cloud computing systems between nations and cloud providers is an essential task for modern economies, national security, and ways of life. This report argues that cloud trust will require collaboration between providers, nation states, and customers, but should not start with location requirements and geographic restrictions on access to cloud computing. Instead, national cloud policies should prioritize criteria of trust that verifiably and meaningfully improve the security of customer cloud operations.

Introduction

As a component of artificial intelligence deployment, development, and use, as well as an enabling technology for business, government, and critical infrastructure functions, cloud computing is a fixture of cyber policy discussions. Within the emerging AI supply chain, cloud services are the means of deploying ‘compute’, a critical resource powering models in both training and inference throughout the global economy.6For coverage of another element of this supply chain, data, see Justin Sherman’s Securing data in the AI supply chain. This paper aims to offer a nuanced discussion of cloud computing through the consolidation of a shared policy vocabulary and common technical principles to describe and understand trust in cloud computing. By adding detail to how cloud computing is portrayed, policymakers can more effectively understand the systems they’re expected to trust. By adding granularity to existing discussions of cloud computing, policymakers can more effectively understand the systems they are expected to trust and better appreciate how policy shapes both those systems and that trust.

Attackers continuously scan public-facing devices and infrastructure for misconfigurations and weaknesses.7Bar Kaduri and Tohar Braun, “2023 Honeypotting in the Cloud Report: Attacker Tactics and Techniques Revealed,” Orca Security, 2023, https://orca.security/lp/sp/ty-content-download-2023-honeypotting-cloud-report/. Countries with advanced cyber capabilities, including Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran, show no signs of ceasing cyber threat activity.8“Emerging Threats: Cybersecurity Forecast 2025,” Google Cloud Security, November 13, 2024, https://www.gstatic.com/gumdrop/files/cybersecurity-forecast-2025.pdf. The pace of vulnerability exploitation continues to accelerate, and within days of their public disclosure, attackers weaponize vulnerabilities to gain access to and exploit cloud environments.9“Cloud Attack Retrospective: 8 Common Threats to Watch for in 2025,” Wiz, June 18, 2025, https://www.wiz.io/reports/cloud-attack-report-2025. Meanwhile, policy debates often focus on limiting access from cloud providers to customer information, instead of ensuring the security of such resources and information from adversary access.

Developing a more compelling model and framework for trust in cloud computing requires bridging debates around localization, digital sovereignty, and technical security, as well as emerging trends in artificial intelligence development and deployment. The risks posed to the cloud ecosystem by the unintended consequences of policy intervention are significant, but so too are the consequences of untrusted and insecure cloud deployments.

A shared cloud computing vocabulary

This section will establish essential vocabulary and terms for cloud computing. The terms and characteristics defined here are non-exhaustive but are a useful starting point for cloud policy discussions. Cloud computing describes a model where service providers offer metered, on-demand access to computing resources.10Peter Mell and Timothy Grance, “NIST Special Publication 800-145: The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing,” National Institute of Standards and Technology, September 2011, https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/legacy/sp/nistspecialpublication800-145.pdf. Instead of operating their own servers and facilities, customers specify workloads—sets of defined computing tasks, utilizing computing resources—for which cloud providers handle implementation and execution.11Ashwin Chaudhary, “What is Cloud Workload in Cloud Computing,” Cloud Security Alliance, November 13, 2024, https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/blog/2024/11/13/what-is-cloud-workload-in-cloud-computing. Sometimes the resources used by these workloads are virtual versions of physical resources (“virtual machines” or VMs), but often they are abstract resources or functions, such as data storage or analysis services, and are not rooted in or wedded to specific hardware or software implementations. Cloud providers must manage and architect both individual hardware and software components and the protocols, pathways, and constraints of their communications and interactions. To ensure visibility and reliability, cloud providers must build systems that carefully manage changes, catch and alert on outages, and gracefully handle errors or failures. This model of access to computing resources includes general access to applications and data storage, but also specialized services for specific customers or sectors.

Cloud providers aggregate and distribute workloads across computing resources. Centralized control over the design, development, testing, and maintenance of both hardware and software enables cloud providers to reduce costs while optimizing their services for the performance and reliability needs of customers.12Rolf Harms and Michael Yamartino, “The Economics of the Cloud,” Microsoft, November 2010, https://news.microsoft.com/download/archived/presskits/cloud/docs/The-Economics-of-the-Cloud.pdf. End-to-end control over cloud systems also allows costly experimentation with specially-tailored or developed software and hardware, including custom advanced semiconductors (chips, silicon).13Wenqi Jiang et al., “Data Processing with FPGAs on Modern Architectures,” Companion of the 2023 International Conference on Management of Data, June 4, 2023, 77–82, https://doi.org/10.1145/3555041.3589410. Prominent cloud providers, including Microsoft, Google, and Amazon, derive advantages from both the scale of their cloud infrastructure and their expertise in adjacent fields and product offerings (earning them the name hyperscalers”).14“Gartner Says Worldwide IaaS Public Cloud Services Market Grew 22.5% in 2024,” Gartner, August 6, 2025, https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2025-08-06-gartner-says-worldwide-iaas-public-cloud-services-market-grew-22-point-5-percent-in-2024. For example, Google’s development of its distributed data storage and processing platform BigTable was driven by the computing demands of its search product.15Fay Chang et al., “Bigtable: A Distributed Storage System for Structured Data,” ACM Trans. Comput. Syst. 26, no. 2 (2008): 1-26, https://doi.org/10.1145/1365815.1365816. Embedded within the configurations and offerings available to customers are a cascading sequence of impactful decisions made by cloud service providers. Balancing incentives, imperatives, and resource constraints creates an ever-evolving system of systems that is more than the sum of its parts.

Customers of cloud providers can adjust their use of computing resources elastically. Instead of purchasing physical hardware, launching software, and monitoring it directly for power outages or reliability issues, customers can outsource those responsibilities to cloud providers. This allows companies to focus on their unique products and services instead of monitoring and maintaining networking, energy, and processing equipment. Decomposing workloads into discrete tasks, scheduling tasks for individual hardware components, and monitoring the execution of those tasks for errors, delays, or hardware failures requires carefully optimized software, specific hardware, and dedicated research capabilities.16Aditya Ramakrishnan, “Under the hood: Amazon EKS ultra scale clusters,” Amazon Web Services, July 16, 2025, https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/containers/under-the-hood-amazon-eks-ultra-scale-clusters/. Within nano- or milliseconds, cloud computing systems communicate and synchronize across oceans and continents, ensuring availability and reliability despite frequent outages, hardware failures, and natural disasters. Using metered, elastic cloud services also allows companies to “scale” their computing resource footprint in response to demand.17David Kuo, “Scaling on AWS Part I: A Primer,” AWS Startups Blog, November 25, 2015, https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/startups/scaling-on-aws-part-1-a-primer/. Seasonal surges, such as a boom in visits to e-commerce sites around the holiday season, or daily and weekly patterns, such as workplace software peaking in use during business hours Monday-Friday, no longer require projections months ahead of time, and the build-up of infrastructure to handle maximum demand, which then sits idle outside of specific moments. Instead, enterprises can dynamically and automatically adjust their use of computing resources and services through their cloud providers.18“What is elastic computing or cloud elasticity,” Microsoft, accessed September 4, 2025, https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/resources/cloud-computing-dictionary/what-is-elastic-computing. At the global scale of modern cloud systems, cloud providers triage and respond to issues that would be completely unfamiliar to self-hosted cloud operators accustomed to handling only hundreds or thousands of servers.

Cloud customers and providers optimize the architecture of services to support different computational demands, using distinct technology configurations to execute workloads. Cloud computing architectures dictate “how various cloud technology components, such as hardware, virtual resources, software capabilities, and virtual network systems interact and connect to create cloud computing environments.”19“What is cloud architecture?,” Google Cloud, accessed September 4, 2025, https://cloud.google.com/learn/what-is-cloud-architecture?hl=en. Workloads such as high-definition video streaming, training AI models, and analyzing and extracting information from data have different requirements for synchronicity, availability, reliability, and error tolerance, which demand different choices of software and hardware to balance tradeoffs. By optimizing cloud infrastructure and systems for different tasks, cloud providers can utilize heterogeneous components to their full relative advantages.

As an example, to ensure rapid access to cloud resources, providers maintain and offer content delivery networks (CDNs)—networks of servers and computing resources distributed worldwide to minimize the distance and latency (time delay) between cloud infrastructure and end-users.20Vijay Kumar Adhikari et al., “Unreeling Netflix: Understanding and Improving Multi-CDN Movie Delivery,” Princeton Computer Science, accessed September 4, 2025, https://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/fall16/cos561/papers/NetFlix12.pdf. Cloud providers also maintain points of presence, or edge locations, where their infrastructure connects with internet service providers, on-premise customers, or other cloud providers.21“What is a data center?” Cloudflare, accessed September 4, 2025, https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/cdn/glossary/data-center/. These points of connection include Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) and other co-location services, a subset of which are sometimes referred to as peering locations.22Shweta Jain, “What’s in a Name? Understanding the Google Cloud Network ‘Edge’,” Google Cloud, February 22, 2021, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/networking/understanding-google-cloud-network-edge-points. Network infrastructure, including edge servers, is a critical vantage point for information useful for security monitoring and incident response. Security practices involving network infrastructure range from mitigating attacks that attempt to overwhelm servers with large amounts of requests to limiting unauthorized access to data and cloud resources.23“Cloudflare Security Architecture,” Cloudflare Docs, accessed September 4, 2025, https://developers.cloudflare.com/reference-architecture/architectures/security/.

Cloud computing and artificial intelligence

Cloud computing is involved in AI development and deployment at every stage, from providing data storage and structures to enabling interactions between models and users, all while serving as a central hub of monitoring and evaluation for AI systems. Artificial intelligence companies have close financial and technical relationships with hyperscale cloud providers, and cloud providers themselves develop their own AI models and integrate them with other products. This section will give a brief overview of the importance of cloud computing to artificial intelligence development and deployment as a component of the broader compute infrastructure used in the development and deployment of AI systems.

Emerging players, sometimes referred to as neo-clouds, also offer cloud computing services specific to artificial intelligence workloads. CoreWeave, Lambda, Crusoe, and Nebius all operate under this model.24“Can a $9bn deal sustain CoreWeave’s stunning growth?” The Economist, July 10, 2025, https://www.economist.com/business/2025/07/10/can-a-9bn-deal-sustain-coreweaves-stunning-growth. These companies are financially intertwined with both existing hyperscale cloud providers and key chipmaker NVIDIA. NVIDIA has invested in both Lambda and CoreWeave, in addition to its own quasi-cloud offering, which is built on the infrastructure of other cloud service providers.25Asa Fitch, “Nvidia Ruffles Tech Giants With Move Into Cloud Computing,” The Wall Street Journal, June 25, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/tech/ai/nvidia-dgx-cloud-computing-28c49748; Matt Rowe, “NVIDIA starts to invest in cloud computing,” Due, July 1, 2025, https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/nvidia-starts-invest-cloud-computing. Oracle has contracted Crusoe to build out compute offerings for OpenAI as part of the Stargate project.26Stephen Nellis and Anna Tong, “Behind $500 billion AI data center plan, US startups jockey with tech giants,” Reuters, January 23, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/technology/artificial-intelligence/behind-500-billion-ai-data-center-plan-us-startups-jockey-with-tech-giants-2025-01-23/. Microsoft was responsible for 62 percent of CoreWeave’s 2024 revenue, while Google recently inked a deal to use CoreWeave to deliver computing resources to OpenAI.27Krystal Hu and Kenrick Cai, “CoreWeave to offer compute capacity in Google’s new cloud deal with OpenAI, sources say,” Reuters, June 11, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/coreweave-offer-compute-capacity-googles-new-cloud-deal-with-openai-sources-say-2025-06-11/. These interactions and overlaps all complicate the cloud ecosystem, creating new, interdependent players and novel connections among long-established entities. These new relationships could complicate existing patterns of information sharing and incident response practices, while emerging players have yet to establish long-term track records of security and reliability.

Hyperscale cloud providers have also invested extensive resources in creating and expanding cloud offerings to support AI workloads and to provide access to AI models for their customers within cloud offerings. Examples include AWS’s managed container offerings, which Anthropic uses to execute training and inference workloads at “ultra” scale, as well as tailoring of existing services, plugins, monitoring agents, credentials, and caching features.28Ramakrishnan, “Under the hood.” AWS’s Bedrock offering provides access to several models, including Anthropic’s.29“Amazon Bedrock,” Amazon Web Services, last accessed September 4, 2025, https://aws.amazon.com/bedrock/. Microsoft’s Azure managed cloud offerings monitor, orchestrate, and execute AI workloads, including inference for OpenAI’s models.30Zachary Cavanell, “Meet the Supercomputer that runs ChatGPT, Sora & DeepSeek on Azure (feat. Mark Russinovich),” Microsoft Mechanics Blog, June 5, 2025, https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/blog/microsoftmechanicsblog/meet-the-supercomputer-that-runs-chatgpt-sora–deepseek-on-azure-feat-mark-russi/4418808. Google Cloud’s Cloud TPU platform includes a compiler, managed software frameworks, and custom chips designed to accelerate AI workloads and is used both internally at Google and by companies like Cohere, Stability AI, and Character AI.31Alex Spiridonov and Gang Ji, “Cloud TPU v5e accelerates large-scale AI inference,” Google Cloud, August 31, 2023, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/compute/how-cloud-tpu-v5e-accelerates-large-scale-ai-inference; Nisha Mariam Johnson and Andi Gavrilescu, “How to scale AI training to up to tens of thousands of Cloud TPU chips with Multislice,” Google Cloud, August 31, 2023, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/compute/using-cloud-tpu-multislice-to-scale-ai-workloads; Joanna Yoo and Vaibhav Singh, “How Cohere is accelerating language model training with Google Cloud TPUs,” Google Cloud, July 27, 2022, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/ai-machine-learning/accelerating-language-model-training-with-cohere-and-google-cloud-tpus.

Scarcity or lack of access to key computing resources specific to artificial intelligence could also drive customers to overlook security requirements, focusing instead on rapid access to essential computing power. The increasing compute demands of AI firms and the growth of niche cloud computing service companies, both intertwined with hyperscale cloud providers, will continue to strain existing compute resources such that cloud computing policy interventions run a growing risk of compromising a fragile ecosystem.

Policymaking in this sector has largely focused on advanced semiconductors, particularly NVIDIA GPUs, as the principal component of AI compute, from the Biden administration’s AI diffusion rule to the Trump administration’s AI Action Plan.32“FACT SHEET: Ensuring U.S. Security and Economic Strength in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” Executive Office of the President, January 13, 2025, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2025/01/13/fact-sheet-ensuring-u-s-security-and-economic-strength-in-the-age-of-artificial-intelligence/; “America’s Action Plan,” Executive Office of the President, July 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Americas-AI-Action-Plan.pdf. Proposals have also examined the challenges of securing model weights, managing the flow of advanced semiconductors used in AI training development, and acquiring energy and land needed to construct datacenters.33Sella Nevo, et al., “Securing AI Model Weights,” RAND, May 30, 2024, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2849-1.html; Janet Egan, “Global Compute and National Security,” Center for a New American Security, July 29, 2025, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/global-compute-and-national-security; Tim Fist, Arnab Datta, and Brian Potter, “”Compute in America: Building the Next Generation of AI Infrastructure at Home,” June 10, 2024, https://ifp.org/compute-in-america/#part-ii-how-to-build-the-future-of-ai-in-the-united-states.

However, limited attention has focused on the risks and opportunities of cloud computing’s role in AI development and deployment, and as an essential component of the AI supply chain itself. Efforts to secure the cloud computing ecosystem can protect sensitive intellectual property involved in AI development in deployment, including model weights and proprietary details of both AI use and research methods and practices used to develop frontier AI models. Conversely, policies and security practices that hamper efforts to secure cloud computing infrastructure could jeopardize the security of AI development and deployment.

Building trust

Trust, in this paper, refers to both the ability of cloud customers to ensure that their cloud configurations are secure from external threats and from excessive interference or access from cloud providers themselves. Quickly verifying trustworthiness after a violation is paramount for customers wanting to keep up with attackers. This section will discuss the challenge of establishing trust in cloud computing systems. Miscommunication and misalignment regarding trust have immediate consequences for cloud customers, who often bear the costs of security incidents.

Threat intelligence from cloud security firms suggests that the pace of incidents is increasing, with a 2024 Google Cloud report finding only five days of average observed time between the disclosure and exploitation of vulnerabilities, down from 32 days in 2023.34“Cybersecurity Forecast 2026 report,” Google Cloud, https://cloud.google.com/security/resources/cybersecurity-forecast?hl=en. Another 2023 report from Orca Security found that it took only two minutes for AWS encryption keys that were publicly exposed on GitHub to be used by threat actors.35“2023 Honeypotting in the Cloud Report,” Orca Security, https://orca.security/lp/sp/ty-content-download-2023-honeypotting-cloud-report/. Sophisticated attackers have targeted companies, such as Cloudflare, that specialize in cloud network infrastructure, stealing credentials to access documentation and source code.36Matthew Prince, John Graham-Cumming, Grant Bourzikas, “Thanksgiving 2023 security incident,” Cloudflare Blog, February 2, 2024, https://blog.cloudflare.com/thanksgiving-2023-security-incident/. Advisories from cybersecurity companies and intelligence agencies indicate that organizations persistently experience breaches from sophisticated, nation-state-sponsored threat actors who utilize publicly known vulnerabilities as part of a global espionage strategy.37“Countering Chinese State-Sponsored Actors Compromise of Networks Worldwide to Feed Global Espionage System,” Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), September 03, 2025, https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa25-239a. Meanwhile, trust deficits that result from customers’ lack of trust in cloud providers, or an inability by cloud providers to verifiably demonstrate trustworthiness, hamper both the adoption of cloud capabilities and the ability of organizations to prevent and respond to security incidents. When trust criteria are insufficient or incomplete, preventable incidents can occur at breathtaking speed.

In policy contexts, trust frequently centers on an entity-based definition. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) notes that trust is “a belief that an entity meets certain expectations and therefore, can be relied upon.”38“Glossary: Trust,” National Institute of Standards and Technology, Computer Security Resource Center, https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/trust. A focus on entities can lead to technology policies focused on static, easily verifiable attributes, such as the national origin or corporate headquarters of cloud providers, from which policymakers derive restrictions on specific firms or sweeping prohibitions against foreign entities. This dynamic is not exclusive to cloud computing policy and has occurred throughout national security debates over trusted technology, from Kaspersky to Huawei.39Joe Warminsky, “Kaspersky Added to FCC List That Bans Huawei, ZTE from US Networks,” CyberScoop, March 25, 2022, https://cyberscoop.com/kaspersky-fcc-covered-list/. While organizational attributes can provide useful information, requirements exclusively based on entity-based definitions of trust can overlook technical security measures and implementation details that directly affect system trustworthiness, while incentivizing the use of proxy companies and circuitous legal setups.

Technical communities have developed alternative approaches to trust that emphasize continuous verification instead of static, binary decisions to trust or not trust a technology provider. The zero-trust security model operates on “the premise that trust is never granted implicitly but must be continually evaluated,” according to NIST.40Scott Rose et al., NIST Special Publication 800-207: Zero Trust Architecture, August 2020, https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/specialpublications/NIST.SP.800-207.pdf. This model is a shift from a perimeter-based security strategy toward contextually securing and restricting access to dynamic computing resources and assets.41“Zero Trust Maturity Model,” CISA, January 2022, https://www.cisa.gov/zero-trust-maturity-model. As an illustrative example, a zero-trust approach would reflect a company’s decision to shift from a sign-in system to enter a building, after which each person would have complete access to move around a building, to an approach where each room or floor requires a special key that only certain people can access, regardless of whether or not the person requesting access is already within the building. However, zero-trust is more of a broad set of principles than a set of specific operational requirements and might not align with existing organizational structures and regulatory frameworks that mandate perimeter-based security approaches.

Cryptographic and hardware-based verification mechanisms offer another path through technical, not organizational, assurances. Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) and confidential computing could enable remote attestation of the integrity and confidentiality of data and code.42Suzanne Ambiel, “The Case for Confidential Computing,” The Linux Foundation https://www.linuxfoundation.org/hubfs/Research%20Reports/TheCaseforConfidentialComputing_071124.pdf?hsLang=en; “Trusted Execution Environment (TEE),” Microsoft Learn, accessed September 4, 2025, https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/confidential-computing/trusted-execution-environment. Remote attestation and technical assurances can establish trust outside of organizational attributes but require specialized hardware and software implementations that are not currently widely available or cost-effective.43“A Technical Analysis of Confidential Computing,” Confidential Computing Consortium, November 2022, https://confidentialcomputing.io/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2023/03/CCC-A-Technical-Analysis-of-Confidential-Computing-v1.3_unlocked.pdf.

These divergent approaches to trust create challenges for cloud providers and customers. A coherent, cohesive approach to cloud trust must bridge different methods while accounting for the scale and complexity of cloud computing. This requires moving beyond simple analogies and one-size-fits-all policies towards frameworks that thoughtfully weigh technical and organizational attributes. The alternative is a fragmented system in which policies undermine the economic and technical benefits of cloud computing without improving security. The costs of insecurity will only grow as the cloud becomes more entwined with AI applications, making the question of ensuring trust in cloud computing increasingly critical.

Digital sovereignty and data localization

This paper’s focus is on digital sovereignty policies that target cloud infrastructure, such as the promotion of national or local alternatives to cloud providers, the exclusion of foreign cloud providers from specific certifications or sectors, or restrictions on the structure and configuration of cloud deployments within national borders.44Max Von Thun, “Cloud computing is too important to be left to the Big Three,” The Financial Times, May 26, 2025, https://www.ft.com/content/5c930686-9119-402d-8b9b-4c3f6233164e; “Navigating Digital Sovereignty and its Impact on the Internet,” The Internet Society, December 2022,https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Digital-Sovereignty.pdf; Laurens Cerulus, “France wants cyber rule to curb US access to EU data,” Politico, September 13, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/france-wants-cyber-rules-to-stop-us-data-access-in-europe/; “Towards a next generation cloud for Europe,” European Commission, October 15, 2020, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/towards-next-generation-cloud-europe; Tony Roberts and Marjoke Oosterom, “Digital authoritarianism: a systematic literature review,” Information Technology for Development (2024): 1-25, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02681102.2024.2425352?af=R#d1e129 https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Digital-Sovereignty.pdf. This section will ground this paper’s discussion of trust and security in cloud computing and infrastructure within a contemporary policy debate: the application of digital sovereignty and data localization restrictions to cloud computing.45“Navigating Digital Sovereignty and its Impact on the Internet.”

In many cases, companies that qualify as hyperscalers also offer search engines, operating systems, social media sites, and ad platforms, which could also be relevant to digital sovereignty debates. Those offerings remain outside of the scope of this paper but could very well have implications for cloud computing if remedies or policies aimed at achieving digital sovereignty goals impacted hyperscale providers and their cloud offerings.

There are at least three essential characteristics of digital sovereignty and data localization policies with direct implications for cloud computing: the affected country or region, the scope of customers affected, and the criteria for cloud trust. In addition to descriptions, each characteristic will include illustrative examples.

Table 1: Key characteristics for digital sovereignty policies affecting cloud computing systems

Geography

The first essential characteristic is the geographic region affected by a policy. Typical examples of cloud sovereignty or digital sovereignty policies apply at a national level and are set by a federal policymaking body.

For example, the French SecNumCloud certification scheme, which includes localization requirements and restrictions on foreign ownership of cloud providers, is in effect within France.46Georgia Wood and James Lewis, “The CLOUD Act and Transatlantic Trust,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 29, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/cloud-act-and-transatlantic-trust; Frances G. Burwell and Kenneth Propp, Digital Sovereignty in Practice: The EU’s Push to Shape the New Global Economy, Atlantic Council, October 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Digital-sovereignty-in-practice-The-EUs-push-to-shape-the-new-global-economy_.pdf. Attempts to extend sovereignty policies in certification requirements across the EU within the European Union Cybersecurity Certification Scheme for Cloud Services have been unsuccessful so far, facing opposition from Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Lithuania, Poland, Sweden, and the Netherlands.47Meredith Broadbent, “The European Cybersecurity Certification Scheme for Cloud Services,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), September 1, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/european-cybersecurity-certification-scheme-cloud-services. Outside the EU, digital sovereignty policies appear to remain national in scope, which aligns with the focus of supporters of some digital sovereignty policies in ensuring government control over and visibility into cloud services.

Scope

Another essential characteristic is the scope of customers or procurers of cloud services affected by digital sovereignty policies. Direct government use of cloud services or use by critical infrastructure sectors like finance and defense have been a focus of digital sovereignty policies. These policies can take the form of explicit bans or prohibitions on critical sector or government use of foreign cloud providers, procurement incentives for local companies, or technical requirements that in effect mandate country or sector-specific cloud configurations.

Several countries and geographies have experimented with sovereignty and localization requirements specific to critical infrastructure sectors or government use. The Cross Border Data Forum’s 2021 data localization report highlighted requirements for exclusive localization of financial sector information and operations, such as transactions and banking information, in several countries, including South Africa, Turkey, and India.48Nigel Cory and Luke Dascoli, “How Barriers to Cross-Border Data Flows Are Spreading Globally, What They Cost, and How to Address Them,” Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, July 19, 2021, https://itif.org/publications/2021/07/19/how-barriers-cross-border-data-flows-are-spreading-globally-what-they-cost/. The aforementioned French SecNumCloud scheme applies to government agencies and “operators of national importance.”49Broadbent, “The European Cybersecurity Certification Scheme for Cloud Services.” South Korea’s Cloud Security Assurance Program (CSAP) applies to public sector cloud use, but debates over its provisions have suggested it could be extended to additional sectors such as healthcare and education.50“South Korea’s Cloud Service Restrictions,” Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, August 26, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/05/25/south-korea-cloud-service-restrictions/.

The sensitivity of government and critical infrastructure sector data and operations raises heightened concerns regarding the risks of unauthorized access to information or disruption of services. The sheer size of the government and critical infrastructure sectors’ cloud budgets also creates an appealing policy target, as including requirements or incentives within procurement regimes serves as an intermediary between economy-wide regulations and no regulation at all. Government and critical infrastructure criteria for cloud computing are often thought to induce effects outside of their direct targets, as other companies and organizations incorporate or reference criteria used by those entities in their own cloud procurement decisions.51James Andrew Lewis and Julia Brock, “Faster in the Cloud,” CSIS, January 16, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/faster-cloud-federal-use-cloud-services.

Criteria for trust

The final essential characteristic of digital sovereignty policies applying to cloud infrastructure is the criteria for trust that policies reference or create. Criteria of trust can include restrictions on nationality or operational jurisdictions of cloud providers, geographic locations of cloud infrastructure, or specific technical and operational measures, such as the use of encryption or external key management. These criteria can be directly put into force through legislation or through references to external certifications or standards bodies.

Digital sovereignty policies often seek to ensure that cloud service providers have local physical footprints. Ensuring the physical footprint of a technology provider can create a toehold for further enforcement and oversight, clarifying the obligations of cloud providers to the citizens and laws of different countries. Without a clear presence in the form of personnel or physical infrastructure in a country, it is difficult for governments to enforce regulations or to substantively hold companies accountable for abuses or violations of policy. Russia and Vietnam both adopted policies requiring local offices and representatives for technology companies, which have been described as creating opportunities for government control and coercion.52Justin Sherman, “The Kremlin May Make Foreign Internet Companies Open Offices in Russia,” Slate, February 8, 2021, https://slate.com/technology/2021/02/russia-kremlin-internet-controls-foreign-companies-offices.html. Incentives for local data center construction, such as Brazil’s proposed package of incentives and tax breaks for developers, can alternatively focus on the potential economic benefits of localized infrastructure, from collected taxes to construction and maintenance jobs.53Lais Martins, “Brazil is Handing Out Generous Incentives for Data Centers, But What it Stands to Gain is Still Unclear,” Tech Policy Press, May 22, 2025, https://www.techpolicy.press/brazil-is-handing-out-generous-incentives-for-data-centers-but-what-it-stands-to-gain-from-it-is-still-unclear/.

Other localization requirements seek to restrict the physical location of cloud infrastructure. Proponents of data localization argue that restricting the physical location of data, including prohibiting cross-border data transfers, provides security and privacy advantages. Countries around the world have adopted localization measures applicable to various sectors, types of data, or processing requirements. Localization measures mandate restricting operations to cloud infrastructure located within certain geographic boundaries. Often, this manifests as restricting the set of cloud “regions” that companies have access to, while cloud providers recommend structuring applications to span multiple regions and availability zones.“54Regions and zones,” Google Cloud, accessed September 4, 2025, https://docs.cloud.google.com/compute/docs/regions-zones. Availability zones are logically isolated segments of cloud infrastructure that attempt to ensure that if one zone suffers an outage, it does not take down other zones within the same region.55“Cloud Locations,” Google Cloud, last accessed September 4, 2025, https://cloud.google.com/about/locations. However, region-wide disruptions such as October’s AWS DynamoDB incident in the us-east-1 region, while rare, have significant impacts on both customers relying on resources within a region and cloud service providers that operate within a specific region.56“Summary of the Amazon DynamoDB Service Disruption in the Northern Virginia (US-EAST-1) Region,” Amazon Web Services, accessed September 4, 2025, https://aws.amazon.com/message/101925/.

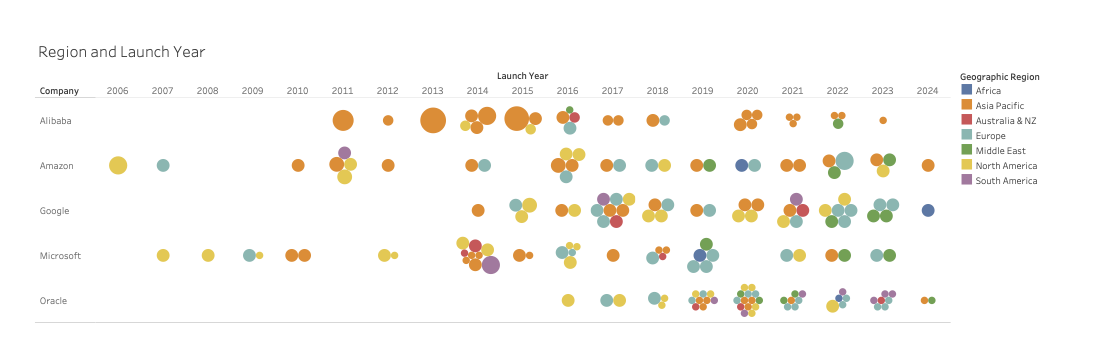

Figure 1: Region and launch year

Restricting the flow of data and information can limit access to computing and processing resources, limiting the ability of cloud providers to surge capacity and geographically distribute workloads. The ability to migrate workloads and computing assets, such as data, to other countries is essential for effective disaster recovery, which could motivate carving out backups as exempt from data localization. In preparing for Russia’s invasion, for instance, Ukraine paused localization requirements and shifted essential government data to cloud infrastructure outside of its borders to ensure availability and access in the event of the physical destruction of domestic data centers.57Catherine Stupp, “Ukraine Has Begun Moving Sensitive Data Outside Its Borders,” The Wall Street Journal, June 14, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/ukraine-has-begun-moving-sensitive-data-outside-its-borders-11655199002. Estonia has also established a data embassy, which consists of an external private cloud region in Luxembourg to ensure continuity of government operations in the event of a crisis.58“e-Governance,” e-Estonia, last accessed September 4, 2025, https://e-estonia.com/solutions/e-governance/data-embassy/.

Beyond infrastructure locations, countries and customers might seek to restrict the geographic location of technical support staff and engineers, especially individuals who might access or view sensitive data. Requirements can restrict physical location, citizenship, or clearance of support personnel, which can impact the staffing strategies, create challenges for around-the-clock availability, and require duplication of expertise across nations. According to ProPublica, Microsoft worked around such restrictions from the United States Defense Department by using support structures such as “digital escorts,” where individuals in possession of security clearances but lacking technical expertise supervised engineers, including engineers physically located in China, as they interacted with cloud systems used for national security purposes.59Renee Dudley and Doris Burke, “A Little-Known Microsoft Program Could Expose the Defense Department to Chinese Hackers,” Pro Publica, July 15, 2025, https://www.propublica.org/article/microsoft-digital-escorts-pentagon-defense-department-china-hackers. The impulse towards workarounds for location-based restrictions, such as the digital escort system, which Microsoft has reportedly stopped using for the Department of Defense, demonstrates the operational difficulties restrictions on the location of support staff can create and the security risks that can result from the uneven implementation of location restrictions.60Renee Dudley, “Microsoft Says It Has Stopped Using China-Based Engineers to Support Defense Department Computer Systems,” Pro Publica, July 18, 2025, https://www.propublica.org/article/defense-department-pentagon-microsoft-digital-escort-china.

Infrastructure localization approaches can also be designed to ensure that companies or governments have local oversight and control over security measures, including the use of encryption. Keeping encryption keys off cloud provider infrastructure, and instead on local or on-premise infrastructure, can be referred to as “key escrow” or “external key management.”61Anton Chuvakin and Il-Sung Lee, “The cloud trust paradox: 3 scenarios where keeping encryption keys off the cloud may be necessary,” Google Cloud, February 2, 2021, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/identity-security/3-scenarios-where-keeping-encryption-keys-off-the-cloud-may-be-necessary. Apple has historically complied with key localization requirements in China, while Google has implemented an offering designed for compliance with a requirement in Saudi Arabia.62Tom McKay, “Apple Moves Chinese iCloud Encryption Keys to China, Worrying Privacy Advocates,” Gizmodo, February 25, 2018, https://gizmodo.com/apple-moves-chinese-icloud-encryption-keys-to-china-wo-1823312628; Archana Ramamoorthy and Bader Almadi, “Google Cloud expands services in Saudi Arabia, delivering enhanced data sovereignty and AI capabilities,” Google Cloud, August 19, 2024, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/identity-security/google-cloud-expands-services-in-saudi-arabia-delivering-enhanced-data-sovereignty-and-ai-capabilities. These offerings may be developed in partnership with local providers, who can oversee cloud provider access to encryption keys.63Il-Sung Lee, “Use third-party keys in the cloud with Cloud External Key Manager, now beta,” Google Cloud, December 17, 2019, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/identity-security/cloud-external-key-manager-now-in-beta. However, this approach introduces distinct risks to cloud computing systems, as customers must trust the additional provider to secure encryption keys, which, if compromised, would provide access to sensitive data. Countries can also impose other requirements relating to encryption, such as country-specific standards. South Korea’s government cloud certification requires national standard encryption algorithms that are not widely used outside of Korea.64Esperanza Jelalian, “Subject: Public Consultation on Amendments to Korea’s Cloud Security Assurance Program (CSAP),” US-Korea Business Council, US Chamber of Commerce, February 9, 2023, https://www.uschamber.com/assets/documents/U.S.-Chamber_USKBC_CSAP-Letter-to-MSIT-02-09-2023.pdf.

In the US, debates on state-sponsored, proprietary encryption standards have resulted in concerns about the intelligence community creating “backdoors,” or exploitable flaws within encryption algorithms, which could be used by intelligence agencies and malicious actors to monitor communications and access content.65Bryan H. Choi, “NIST’s Software Un-Standards,” Lawfare, March 7, 2024, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/nist’s-software-un-standards. Governments could also directly restrict the ability of cloud service providers to offer products with certain encryption standards or features. The UK’s secret law enforcement request to Apple to access certain encrypted communications led Apple to withdraw its Advanced Data Protection feature from the UK market rather than create a backdoor for authorities.66Zoe Kleinman, “UK backs down in Apple privacy row, US says,” BBC News, August 19, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cdj2m3rrk74o. Restrictions or constraints on encryption standards and encryption system architectures can give local authorities control over access to encrypted data, but can also create vulnerabilities if they result in compromising key local management systems or mandates for insecure encryption standards.

The jurisdictions cloud providers originate from or operate within can be a source of concern for governments, especially when other governments mandate, incentivize, or promote practices that undermine the security of underlying technology systems. Digital sovereignty policies can aim to exclude specific cloud providers or providers from certain countries, either with outright bans or structural requirements mandating local partnerships. The approach of excluding specific countries, or restricting the access of companies from certain countries, is referred to as a blacklist, while a policy that only allows transfers to specified countries is referred to as a whitelist.67Kenneth Propp, Who’s a national security risk? The changing transatlantic geopolitics of data transfers, Atlantic Council, May 29, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/whos-a-national-security-risk-geopolitics-of-data-transfers/.

The United States has typically taken a blacklist approach to national security reviews of foreign companies, imposing a smaller, ad-hoc set of limitations on companies’ jurisdictions and origins. For example, the US government has expressed skepticism over Chinese cloud providers’ access to American information, resulting in investigations of Alibaba’s cloud business.68Alexandra Alper, “Exclusive: U.S. examining Alibaba’s cloud unit for national security risks – sources,” Reuters, January 19, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/technology/exclusive-us-examining-alibabas-cloud-unit-national-security-risks-sources-2022-01-18/. These concerns include Chinese policies requiring technology companies to notify the government when they discover technical vulnerabilities and extensive cooperate with defense and intelligence services.69Peter Harrell, “Managing the Risks of China’s Access to U.S. Data and Control of Software and Connected Technology,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 30, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2025/01/managing-the-risks-of-chinas-access-to-us-data-and-control-of-software-and-connected-technology?lang=en. In reviews of other technical systems, such as telecommunications infrastructure, the US has weighed the national security risks of the involvement of both Chinese and Russian companies.70Communications Networks Safety and Security, US Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportiation, Subcommittee on Communications, Media, and Broadband, 117th Cong. (2024) (written statement of Justin Sherman, Nonresident Senior Fellow, Atlantic Council Cyber Statecraft Initiative), https://www.commerce.senate.gov/services/files/9D566360-52C7-4FB9-B30B-1A5A86B9A69E.

Meanwhile, European data protection regimes, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), utilize a whitelist approach, requiring “adequacy decisions” to approve data transfers to certain countries.71Propp, Who’s a national security risk? European leaders have raised concerns about US surveillance practices and the lack of federal privacy legislation, which has prompted regulators to revoke previous data transfer agreements.72Caitlin Fennessy, “The ‘Schrems II’ decision: EU-US data transfers in question,” IAPP, July 16, 2020, https://iapp.org/news/a/the-schrems-ii-decision-eu-us-data-transfers-in-question. The dominance of US hyperscale cloud providers, domestically and abroad, has led to a close focus in policy discussions on US legislation applicable to cloud providers, including those that affect the operations of cloud providers in other jurisdictions. Concerns regarding US government access to information have led to repeated references in policy debates to one piece of legislation: the 2018 Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act.

The CLOUD Act restated requirements of the US Stored Communications Act (SCA) as they apply to information under the control of cloud providers, including if that information is shared, sharded (splitting data into multiple, more manageable pieces), or distributed across geographic locations, but did not change the requirements for warrants under US law to access the content of electronic communications.73“Promoting Public Safety, Privacy, and the Rule of Law Around the World: The Purpose and Impact of the CLOUD Act,” US Department of Justice, April 2019, https://www.justice.gov/criminal/media/999601/dl?inline. The CLOUD Act’s clarification of the SCA’s scope brought the United States into compliance with the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime, while also authorizing bilateral agreements for countries to request information from cloud providers for law enforcement investigations outside of the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT) process.74“Deputy Assistant Attorney General Richard W. Downing Delivers Remarks at the 5th German-American Data Protection Day on ‘What the U.S. Cloud Act Does and Does Not Do,’” US Department of Justice, May 16, 2019, https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/speech/deputy-assistant-attorney-general-richard-w-downing-delivers-remarks-5th-german-american. The EU-US Data Privacy Framework currently holds an adequacy decision, allowing individual US companies to transfer data under GDPR. However, the Trump administration’s disruption of the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) and US intelligence community data collection have raised questions in Europe about the merits of the adequacy decision and could result in further legal challenges, which could remove the United States and American companies from the GDPR whitelist.75Brian Hengesbaugh and Lukas Feiler, “How could Trump administration actions affect the EU-US Data Privacy Framework?” IAPP, February 26, 2025, https://iapp.org/news/a/how-could-trump-administration-actions-affect-the-eu-u-s-data-privacy-framework-; “Joint answer given by Mr. McGrath on behalf of the European Commission,” European Parliament, April 14, 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-10-2025-000520-ASW_EN.html.

Concerns about the market dominance of US hyperscalers, as well as US government access to content stored on cloud computing systems, have also led to various European initiatives to foster domestic alternatives, such as the GAIA-X initiative.76Mark Scott and Francesco Bonfiglio, “Why Europe’s Cloud Ambitions Have Failed,” AI Now Institute, October 15, 2024, https://ainowinstitute.org/publications/xi-why-europes-cloud-ambitions-have-failed. Foreign ownership restrictions contained within cloud certifications, such as the SecNumCloud regime, have led cloud providers to set up operations and joint ventures with domestic companies that manage local configurations of cloud computing. In France, for instance, Google has partnered with Thales, while Microsoft has partnered with Orange and Capgemini.77“’Cloud de Confiance’ leader,” s3ns, accessed September 4, 2025, https://www.s3ns.io/en; Judson Althoff, “Announcing comprehensive sovereign solutions empowering European organizations,” Microsoft, June 16, 2025, https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2025/06/16/announcing-comprehensive-sovereign-solutions-empowering-european-organizations/. Hyperscale cloud providers have also announced commitments to expand “sovereign” cloud regions, such as Microsoft’s partnership with a German SAP subsidiary, which will consist of “a sovereign cloud platform for the German public sector, hosted in German datacenters and operated by German personnel.”78Brad Smith, “Microsoft announces new European digital commitments,” Microsoft, April 30, 2025, https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2025/04/30/european-digital-commitments/. AWS’s sovereign cloud commitment language also highlights the physical and logical isolation of a forthcoming sovereign European cloud region, which will have “no operational control outside of EU borders.”79Colm MacCarthaign, “Establishing a European trust service provider for the AWS European Sovereign Cloud,” Amazon Web Services, July 10, 2025, https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/security/establishing-a-european-trust-service-provider-for-the-aws-european-sovereign-cloud/. These commitments and infrastructure developments require significant investments as well as a shift in operational and management strategies from the existing global distributed models.

Table 2: Illustrative policies mapped to characteristics for digital sovereignty policies affecting cloud computing systems

Implications for cybersecurity and AI

This multifarious tug of war over sovereignty and trust has significant implications for cloud computing infrastructure, security, and the services, including for AI. Focusing on location as a proxy for control and trust can lead to policies that ultimately undermine security goals by decreasing the reliability and integrity of essential systems. The critical nature of cloud computing means it deserves intensive evaluation to ensure the trustworthiness of foundational systems, but evaluation and assurances of trust in cloud computing should be rooted in effective guarantees. The efficiency and performance benefits of cloud computing are fractured and disrupted by location-based requirements. The replication of infrastructure, support systems, and other operational overhead creates meaningful costs for cloud providers, limiting their ability to invest in other measures that could improve performance or security. Filings by industry organizations, including the US Chamber of Commerce, prove this point by repeatedly highlighting the costs of staff and infrastructure location requirements impose on the operations of cloud providers.80Jelalian, “Subject: Public Consultation on Amendments to Korea’s Cloud Security Assurance Program (CSAP).”

This location requirements race fragments security monitoring and threat response, limiting the ability of organizations with global footprints and technical systems to mitigate and respond to cross-border risks. National or regional silos of cloud deployments with the same underlying software and hardware deployments—all relying on core features, patterns, and architectures developed by the same handful of companies—insulate cloud deployments from legal concerns while creating technical and financial burdens.

Constraints on provider locations and jurisdictions can also limit organizations from taking full advantage of advanced global capabilities, including networking infrastructure. In 2021, for example, Portugal’s Supervisory Authority fined its public census body €4.3 million for using Cloudflare’s services, citing concerns regarding Cloudflare’s global, distributed network of servers and position as a US company.81“The Portuguese Supervisory Authority fines the Portuguese National Statistics Institute (INE) 4.3 million EUR,” European Data Protection Board, December 19, 2022, https://www.edpb.europa.eu/news/national-news/2022/portuguese-supervisory-authority-fines-portuguese-national-statistics_en. Despite Cloudflare’s reputation as a cost-effective and highly reliable network security provider, the ruling occurred in the wake of broader discussions on the ability of European organizations to transfer data to the United States as part of GDPR compliance.82Hendrik Mildebrath, “The CJEU judgment in the Schrems II case,” European Parliament, September 2020, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2020/652073/EPRS_ATA(2020)652073_EN.pdf.

Moreover, the impacts of limiting access to network infrastructure are not mitigated by local datacenters and computing capacity, as organizations will still be unable to use state-of-the-art platforms that enable global communications and stronger security protections. Policies that only consider datacenter capacity and access ignore these impacts and can inadvertently create security issues while degrading service quality.

Governments should avoid imposing restrictions on access to cloud computing based exclusively on the location of cloud infrastructure. Location is at best a proxy for the security practices and guarantees of cloud providers and imposes cost and security consequences on providers. Localization requirements should, at a minimum, involve an advanced notification and blacklist approach, minimizing disruptions and operational concerns for cloud providers who build infrastructure configurations years in advance. Ad-hoc revocation should be reserved for well-documented offenders, observed compromises, and emergencies, as cloud providers, their customers, and the security ecosystem broadly benefit from stability and predictability.

Cloud security fundamentally depends upon the ability of organizations to respond to incidents rapidly at scale. Container escape vulnerabilities, which are errors in the implementation of encryption standards, or misconfigurations in the software connecting different services that expose can data and enable lateral movement, are just a few examples of cybersecurity flaws that are agnostic to the physical location of servers and support staff. If location-based requirements restrict companies’ ability to monitor, observe, and remediate incidents, or even prohibit or discourage them from retaining non-domestic cybersecurity incident response companies, organizations and governments will be cut off from the global flow of cutting-edge threat intelligence, vulnerability reports, and mitigation guidance.83Peter Swire and DeBrae Kennedy-Mayo, “The Risks to Cybersecurity from Data Localization – Organizational Effects,” 8 Arizona Law Journal of Emerging Technologies 3 (June 2025), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4030905.

Conflicting trust frameworks can also undermine the ability of organizations to collaborate across the cloud ecosystem. Instead of working with cutting-edge providers and cybersecurity companies focused on addressing security challenges, organizations are encouraged to turn inward, reinventing the wheel by managing their own technology configurations and security postures. While these organizations have useful context for their own security risks, rapid coordination and information-sharing bolsters collective defenses in ways that are difficult to replicate. Ad-hoc grants and revocations of trust in cloud computing systems or cloud providers exacerbate these challenges, and governments should adopt frameworks for trust that allow for continuous verification and evaluation instead.

The management of cloud encryption keys and credentials is also essential to cloud security. Externalizing key management systems poses enhanced risks for the same reasons that advocates seek to localize control of encryption keys: they unlock access to otherwise secure data.84Anton Chuvakin and Honna Segel, “Unlocking the mystery of stronger security key management,” Google Cloud, December 21, 2020, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/identity-security/better-encrypt-your-security-keys-in-google-cloud. However, removing key management from cloud provider infrastructure and placing it under the control of another provider creates additional risks, as cloud users must now trust each provider and the infrastructure or platform through which keys or identities are managed.85“Cloud External Key Manager,” Google Cloud, accessed September 4, 2025, https://cloud.google.com/kms/docs/ekm#considerations; Chuvakin and Segel, “Unlocking the mystery of stronger security key management;” “Use Secure Cloud Key Management Practices,” US National Security Agency, CISA, March 7, 2024, https://media.defense.gov/2024/Mar/07/2003407858/-1/-1/0/CSI-CloudTop10-Key-Management.PDF. Threat actors have targeted key and identity management platforms, recognizing their importance to the overall security posture of cloud customers. Okta, an identity and management company, has been the subject of repeated attacks, including a breach of its customer support portal, which initially became public because of a threat actor’s boasts on Telegram.86Jonathan Greig, “Okta security breach affected all customer support system users,” The Record, November 29, 2023, https://therecord.media/okta-security-breach-all-support-users; Jonathan Grieg, “Okta apologizes for waiting two months to notify customers of Lapsus$ breach,” The Record, March 27, 2022, https://therecord.media/okta-apologizes-for-waiting-two-months-to-notify-customers-of-lapsus-breach. Removing keys from cloud provider infrastructure does not reduce the importance of securing cryptographic information and credentials, and externalizing key management only places additional responsibility on individual customers to manage and ensure key security.

Cloud security errors and flaws cross organizational boundaries and are not prevented by distinctions between cloud providers and other companies in operating or managing infrastructure. Attackers have leveraged connections between on-premise and public cloud systems (known as hybrid cloud deployments), such as shared credentials or identity systems, to compromise and wreak havoc in cloud environments.87Lior Sonntag, “Bridging the Security Gap: Mitigating Lateral Movement Risks from On-Premises to Cloud Environments,” Wiz, May 25, 2023, https://www.wiz.io/blog/lateral-movement-risks-in-the-cloud-and-how-to-prevent-them-part-4-from-compromis. In a 2023 example, a suspected Iranian threat actor used stolen credentials to move from an on-premise environment into a customer’s Azure configuration.88MERCURY and DEV-1084: Destructive attack on hybrid environment,” Microsoft Threat Intelligence, April 7, 2023, https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/04/07/mercury-and-dev-1084-destructive-attack-on-hybrid-environment/.

Security flaws can also be similar across cloud providers, even when cloud providers separately develop features and products. The cloud security firm Wiz conducted research on the incorporation of a popular open-source database service, PostgreSQL, into cloud platforms and found similar vulnerabilities in Azure and Google Cloud, despite their independent development.89Ronen Shustin, Shir Tamari, Nir Ohfeld, and Sagi Tzadik, “The cloud has an isolation problem: PostgreSQL vulnerabilities affect multiple cloud vendors,” Wiz, August 11, 2022, https://www.wiz.io/blog/the-cloud-has-an-isolation-problem-postgresql-vulnerabilities.

Policymakers should not operate under the assumption that segmenting cloud infrastructure —or the oversight of cloud infrastructure —across organizations will automatically improve the cybersecurity posture of cloud configurations. By limiting the ability of companies to share information about vulnerabilities or observe threat activity across active cloud configurations, policymakers can inadvertently exacerbate the challenge of common security failures across cloud providers. The trajectory of AI development and its intense reliance on cloud resources will only exacerbate the challenges of navigating these tradeoffs. Policies that require jurisdictional independence, exclusive local legal or operational control, and partnerships with local companies incentivize configurations that are not based upon a solid foundation of technical boundaries and isolation. Artificially constraining cloud providers, mandating technology transfer, and rewarding regulatory arbitrage do nothing to advance national sovereignty objectives and incentivize lax security practices instead of proactive, systemic monitoring.

If specific government or critical infrastructure sector criteria for cloud procurement are too onerous or burdensome, they also risk artificially segmenting the cloud market, leaving public sector customers out of step with industry norms and delayed in accessing new offerings. For example, AWS’s US GovCloud region contains detailed documentation on services available in other regions that are unavailable or require distinct configurations within GovCloud.90“Services in AWS GovCloud (US) Regions,” Amazon Web Services, accessed September 4, 2025, https://docs.aws.amazon.com/govcloud-us/latest/UserGuide/using-services.html. A US Government Accountability Office report on federal agency use of generative AI also references delays of cloud certification processes as an obstacle to access and use of new services, particularly when the companies offering them are not interested in gaining authorization through procurement processes or are unaware of federal procurement requirements.91“Artificial Intelligence: Generative AI Use and Management at Federal Agencies,” US Government Accountability Office, July 29, 2025, https://files.gao.gov/reports/GAO-25-107653/index.html.

Critical infrastructure sectors and government agencies already shoulder cybersecurity burdens as the targets of persistent cyberattacks, with consistent ransomware attacks on hospitals as one example.92“Healthcare and Public Health Sector,” CISA, accessed September 4, 2025, https://www.cisa.gov/stopransomware/healthcare-and-public-health-sector. In budget-constrained organizations, interpreting and implementing cybersecurity regulatory requirements can create cost burdens that lead to difficult tradeoffs with essential functionality.93Ashley Thompson, “Re: Cyber Incident Reporting for Critical Infrastructure Act (CIRCIA) Reporting Requirements,” American Hospital Association, July 3, 2024, https://www.aha.org/lettercomment/2024-07-02-aha-responds-cisa-proposed-rule-cyber-incident-reporting-requirements. Policies designed to shape the cloud market broadly should carefully evaluate which sectors are impacted and to what degree. If the goal of a procurement or incentive structure is cross-sector security requirements, public entities with limited cybersecurity expertise or leverage to negotiate with hyperscale cloud providers, such as critical infrastructure operators, may not be a logical starting point.

Governments around the world have a crucial role to play in allowing cloud providers to demonstrate trustworthiness, as they can remove barriers to information sharing, harmonize international trust regimes, and demand information from providers that customers would otherwise be unable to access. Accepting and embracing this role requires a strategic focus outside of the role of governments as merely cloud procurers. While governments are essential users of the cloud, consumer protection mandates and broader security goals merit a focus on ecosystem-wide security, which should be disentangled from direct procurement capabilities. Cloud providers should be required to share cloud security indicators with governments not just as a step to securing public sector contracts, but also to verify the trustworthiness of cloud infrastructure critical to modern society.

The US can play an important role in shepherding confidential computing technology—which runs computations on isolated systems—but must also manage coordination to ensure that by the time this technology is available and trustworthy, that allies and partners have not fully pivoted to regulatory regimes that mandate fragmented cloud infrastructure. One way to assure allies and partners is to demonstrate commitments to the security of the cloud ecosystem. Where legislation like the CLOUD Act has been mis- or over-interpreted by outside entities to provide expansive authorities, law enforcement agencies should continue to clarify the scope and details of warranted access to the content or information stored by cloud providers. Through its oversight functions, the US Congress can also publicize further aggregated, anonymized, and declassified information about the nature of interactions between the intelligence community, law enforcement agencies, and cloud providers, including allowing further information sharing about national security requests.

Conclusion

As artificial intelligence demands force the evolution of cloud computing systems, policies aiming to ensure the security of cloud computing must balance the goals of visibility and control with essential capabilities. Specialized providers and the relative opacity of the AI ecosystem both make cloud computing’s role in AI more critical and fragile. As artificial intelligence workloads continue to require careful coordination across specialized providers and infrastructure, establishing clear criteria of trust in cloud computing gains urgency. The consequences of failing to establish and maintain this trust will not just be felt by organizations using the cloud to develop and deploy artificial intelligence, but by governments and companies broadly, as the cloud infrastructure they depend upon and utilize becomes fragmented and limited.

Countries around the world have implemented and proposed policies that impose geographic or location restrictions on cloud systems, instituting organizational and operational changes for cloud providers without fully evaluating the security tradeoffs. Requirements that change the criteria for trust in cloud computing to prioritize location can silo and fragment cloud infrastructure, reducing geographic distribution that provides resilience and elasticity. Focusing the evaluation of trust instead on technical assurances, rather than geographic and organizational proxies, should be the priority of governments. The location and nationality of cloud providers, while important, are insufficient proxies for security guarantees and outcomes and ultimately serve to incentivize regulatory arbitrage and compliance over state-of-the-art security practices.

The complexity of cloud computing—driven by scale, specialization, and demand—enables the reliable systems and technical innovations that define modern economies and ways of life—and that is why that policies and regulations in this sector need to be finely-tuned and informed by technical realities. Interventions that aim to manage this complexity by tearing apart infrastructure and segmenting it within geographic borders will only end up undermining these systems and their security without fulfilling national security goals.

There is no doubt this is a tall task. But only strategies as nuanced as the technology itself can safeguard its advantages while establishing the foundational trust that will underpin the future of artificial intelligence and technological innovation.

About the author

Sara Ann Brackett is an assistant director with the Cyber Statecraft Initiative, part of the Atlantic Council Tech Programs. She focuses her work on open-source software security, software bills of materials, software liability, and software supply-chain risk management within the Cyber Statecraft Initiative’s cybersecurity and policy portfolio.

Brackett graduated from Duke University, where she majored in computer science and public policy and wrote a thesis on the effects of market concentration on cybersecurity. She participated in the Duke Tech Policy Lab’s Platform Accountability Project and worked with the Duke Cybersecurity Leadership Program as part of Professor David Hoffman’s research team.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Trey Herr, Stewart Scott, Nitansha Bansal, Kemba Walden, Devin Lynch, Justin Sherman, Dominika Kunertova, and Joe Jarnecki for their comments on earlier drafts of this report, as well as all the individuals who participated in background and Chatham House Rule discussions about issues related to data, AI applications, and the concept of an AI supply chain.

Explore the program

The Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative, part of the Atlantic Council Technology Programs, works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology.

Image: Digital landscape with mountains or clouds made of line grid. Image via Shutterstock.