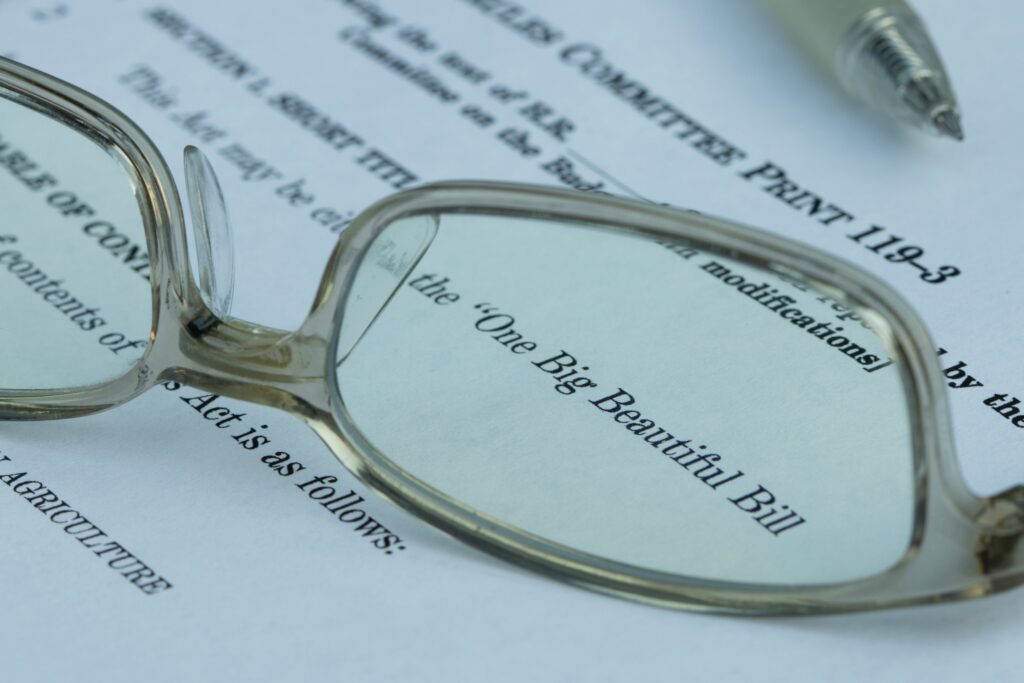

President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act (H.R.1), a sweeping budget reconciliation plan, passed the House of Representatives on May 22, 2025, and is now under review by the US Senate. Buried in its one thousand-plus pages is Section 899, a hitherto obscure clause that could unsettle global capital markets and test investor confidence in America’s financial leadership and market stability.

Section 899 and Trump’s strategy

As passed by the House, Section 899 would empower the Department of the Treasury to publish a quarterly list of “discriminatory foreign countries,” which are jurisdictions that it deems to impose “unfair” taxes on US businesses, such as digital services taxes or the undertaxed profits rule in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Pillar Two minimum tax regime. Notably, the legislation leaves “discriminatory” loosely defined, giving the Treasury broad discretion. Investors from any listed country would face an extra 5 percent US withholding tax on income from US sources (dividends, interest, royalties, etc.), increasing by five points each year up to a maximum of twenty points above the statutory rate. In practical terms, a dividend taxed at 5 percent today could eventually be 25 percent, and income already taxed at statutory 30 percent could reach 50 percent, notwithstanding any rate caps otherwise agreed in existing treaties. Major economies like the United Kingdom, France, Australia, and India have enacted measures that might put them in Section 899’s crosshairs, although the Treasury would have broad, potentially policy-driven discretion to add or remove countries from the target list.

On June 16, the US Senate Finance Committee released its own draft of Section 899, which would cap the provision’s extra tax at fifteen points (not twenty) and delay its application until 2027 for calendar-year taxpayers. It also explicitly exempts portfolio interest from any Section 899 tax hike (meaning that interest on most US Treasury securities would not be subject to the add-on). These changes, likely prompted by intense lobbying from the financial industry since the House passage, would soften, though not eliminate, the potential disincentive for foreign investors to invest in many US assets. Notably, the Senate version substantively retains the House bill’s broad definition of discriminatory taxes and the Treasury’s wide latitude to list targeted countries, meaning the core structure and its potential leverage remain. The Senate is expected to mark up the bill later this summer, but reconciling the House and Senate version will likely stretch into the autumn budget negotiations.

If enacted in a form resembling the House version (or even the Senate Committee draft), Section 899 could give President Trump a potent new economic lever beyond tariffs. Using this lever would effectively extend his “America First” strategy from the realm of trade disputes to cross-border capital flows. It would allow potential taxation of such flows to be utilized to extract concessions from both traditional US allies and rivals. Supporters of the clause contend that brandishing the threat of higher US taxes on foreign investors will pressure other governments to repeal taxes and rules they believe unfairly target American companies. Critics, however, argue that turning access to US financial markets into a weapon is a high-risk gamble. They note that the sheer scale of the potential tax hike, the break with long-standing treaty obligations, and the Treasury’s sweeping latitude to single out countries all contribute to a potentially ominous message for foreign capital and investment.

Investor confidence, capital flows, and the dollar: Global market implications

Foreign investors collectively hold tens of trillions of dollars in US stocks, bonds, and other assets. This capital helps to finance the United States’ federal deficit and keeps borrowing costs in the United States relatively low. A central concern is that Section 899, if enacted, could cause investors to pull back some of this vital foreign capital. The mere prospect of Section 899 has already injected further political risk into assets long prized for predictability. While Section 899’s phased escalation is meant as a hardball negotiating tactic to compel foreign governments to comply before serious damage is done, simply passing such a measure sows a degree of uncertainty for investors.

Long-term investors in particular might pause or reconsider investments in US assets if they perceive that their anticipated returns could be abruptly curbed by political decisions. Even a modest reduction in foreign investment could reverberate across US asset classes. Robust American bond yields and a weaker dollar may have recently provided short-term incentives for foreign buyers. However, America’s long-held reputation for financial outperformance and safety, which has attracted capital even (or particularly) in turbulent times, may erode over time. By signalling that US capital markets could become a geopolitical tool, Section 899 could chip away at a foundation of trust that has underpinned American financial strength.

A shift of foreign investment away from US assets could raise the cost of capital in the United States. Additionally, stock valuations, especially for firms with large international shareholder bases, might face downward pressure. Real assets could be hit too. Multinational companies weighing investments in the United States might rethink major projects if their profits could be skimmed by a special tax contingent on their nationality. The breadth of US financial markets, ranging from government bonds to riskier corporate ventures, could see a collective dampening of foreign demand over time.

More broadly, weaponizing America’s financial heft through a provision like Section 899 may help to accelerate a geopolitical realignment in global finance. The implications extend to currency dynamics, particularly the role of the US dollar. The dollar’s strength as the world’s reserve currency is underpinned by trust that the United States offers a secure and impartial home for capital. If Section 899 leads even a few major international investors to question that premise, the dollar could face additional headwinds. While the Senate Finance Committee’s exclusion of portfolio interest should help mitigate this particular concern by shielding most US government debt from the tax, less appetite for US securities would mean less demand for dollars to buy those assets—arriving at an inopportune moment as US budget deficits widen and reliance on foreign creditors grows. If foreign lenders become less willing to bankroll Washington’s spending, the dollar’s value may weaken further. Some policymakers might welcome a weaker dollar for its boost to exports, but any short-term trade gains could be offset by higher inflation and a diminished appeal as a safe haven.

The outcome of Section 899 will send an important signal. If it passes largely consistent with the House version, President Trump will have a powerful new stick to wield in international economic negotiations, reinforcing his broader message that the United States is willing to upend norms to defend its interests. Using this stick could mark a new era of assertive tax policy with potentially unpredictable consequences for the global investment climate. However, if Congress waters down or removes Section 899, it may reassure investors that the United States seeks to maintain its traditional role as a relatively stable anchor in the global financial system.

John Satory is a senior lawyer with over twenty years of experience in cross-border capital markets based in London and is a contributor to the Atlantic Council.

Data visualization by Ella Wiss Mencke and Jessie Yin.

At the intersection of economics, finance, and foreign policy, the GeoEconomics Center is a translation hub with the goal of helping shape a better global economic future.

Further reading

Wed, May 28, 2025

Does the Nippon Steel deal reflect a new normal for foreign investment in the US?

New Atlanticist By Sarah Bauerle Danzman

The big question now is if the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States process has changed in ways that will affect future deals.

Wed, Mar 19, 2025

Investment screening reform may stifle international investment in US

Econographics By

The Trump administration wants to reform the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US. But what does this actually mean for US industry, investment, and innovation?

Mon, Jun 16, 2025

Did Trump effectively nationalize US Steel with his ‘golden share’?

New Atlanticist By Sarah Bauerle Danzman

The Atlantic Council’s Sarah Bauerle Danzman delves into the details of the recently finalized deal between Nippon Steel and US Steel.